Walter Hopps was a legendary curator of contemporary art who revolutionized the museum realm with radical exhibitions and an enduring support for contemporary art and artists. Published earlier this year, The Dream Colony: A Life in Art, is an autobiographical account of Hopps’s life, compiled by Anne Doran, an arts writer, and edited by Deborah Treisman, fiction editor of The New Yorker. The book includes an introduction by Ed Ruscha, who knew Hopps for many years. The authors visited the Getty earlier this year to talk about the book and Hopps’s lasting impact. This episode is a recording of that conversation.

More to Explore

The Dream Colony: A Life in Art book information

Transcript

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

DEBORAH TREISMAN: “Someone had to find the cave. Someone had to mix the pigments. Someone has to stand there and hold the torch while the artist does it.” And he said, “I’m holding the torch.”

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with Ed Ruscha, Anne Doran, and Deborah Treisman, about their new book on the life and work of the legendary contemporary art curator and museum director Walter Hopps.

When Walter Hopps became the director of Washington’s Corcoran Gallery of Art at age thirty-four, the New York Times described him as “the most gifted museum man on the West Coast (and, in the field of contemporary art, possibly in the nation).” Famous for his groundbreaking exhibitions, his support for living artists, and his extraordinary, eccentric work ethic, Hopps cast a bright and early light on the work of a generation of leading West Coast artists, including Ed Ruscha, Ed Keinholz, Larry Bell, Ed Moses, and Robert Irwin.

The Dream Colony: A Life in Art, published earlier this year, is a vivid and personal account by Walter Hopps of his life, compiled by Anne Doran, and edited by Deborah Treisman, with an introduction by Ed Ruscha.

This summer, Anne, Deborah, and Ed came to the Getty to speak about their book. I moderated the discussion in front of a packed house in the Harold Williams auditorium.

So let’s start with you, Ed. How and when did you meet Walter Hopps? And what was his reputation like when you met him?

ED RUSCHA: Let’s see, I met him about 1960 or ’61, in LA. I met him through Joe Goode, who occupied the back of his house in Pasadena, as a studio. And right away, I knew this guy had some kinda connection to the universe, in a lotta ways. And I could see that he was somebody who was—I mean, he could make a spectator sport out of talking. [laughter]

CUNO: You got here to Chouinard in ’59 or ’58?

RUSCHA: ’59 and ’60, yeah.

CUNO: So you got to Walter right away somehow, within a couple—

RUSCHA: Didn’t meet Walter—I don’t think he ever came to the school there, but he was a figure in the art world that—out on La Cienega, where everything was supposedly happening. I have a vivid memory of him fielding questions. He appreciated when you quizzed him on things, because he had a—an immense memory for all kinds of things relating to art, music, literature, and all that. And he had a way of standing and sort of preparing himself, ready to talk. And he would take a little breather, maybe gulp or two or something, to answer a question. And he’d…

TREISMAN: Light a cigarette.

RUSCHA: …bum a cigarette, light a cigarette, and begin to walk across, pace across the floor. And he more or less, like, glided, rather than walked. Which gave me the idea that this guy can walk on air. [laughter]

CUNO: You say in the introduction, you say that he didn’t live or work by normal standards, that he was never entirely taken up by a job, that he kept odd hours, and that “he had the ability to rhapsodize. He knew everything that was happening in all the crosscurrents,” and that he was more an artist than a businessman.

RUSCHA: Pretty good description of him. [laughter] He—if he was here, he’d agree with me maybe. And if you read the book, you’ll see his connection to the world and how he got interested in art in the very beginning, and he got interested in photography, and he made little photographic collages and all that. All that contributed to his outlook in the world. I mean, he could mix oil and water together. He could make two unlike people get with each other. You know, I’m trying to think of an example.

Would be like, Wally Berman and Ed Kienholz. And as the way Walter described it, Wally felt that Kienholz was too bawdy and crude. And Kienholz thought Wally Berman was “spiritually misty,” [laughter] was his words. Too “spiritually misty.” I like that. But that’s pure Walter Hopps.

CUNO: Yeah. Deborah, tell us how you met Walter. And I know that you met him with Anne.

DEBORAH TREISMAN: Yeah, I met him much, much later than Ed. I was interviewing to be the managing editor of a literary and art quarterly called Grand Street, which was run by Jean Stein, and where Walter was the art editor. And Anne at that point was a contributing editor.

So I was twenty-three at the time, and I didn’t know very much about Walter. I knew the basics about his past. And he wanted to meet at the Temple Bar in New York. Very dark, red-velvet-lined bar. And so I went there sort of nervously, and at some point, about half an hour after our interview time, Walter sauntered in with Anne, with this big fedora on, and plopped down a file of photographs and said, “Well, we’re trying to do this portfolio. Which pictures should we use?” And that was my interview. [Cuno chuckles] And—

ANNE DORAN: She did really well.

TREISMAN: And after— [she chuckles]

CUNO: [over Treisman] There was going to be a portfolio on a theme of some kind.

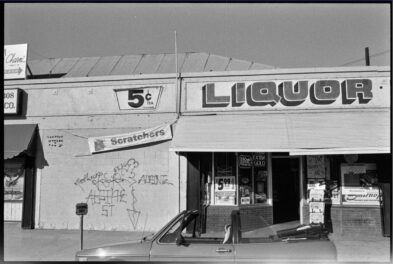

TREISMAN: It was a theme. It was photographs of graffiti memorials to dead gang members. And—

CUNO: That wasn’t your specialty, I assume.

TREISMAN: I had no experience, but I don’t think it mattered. I don’t think it mattered. I think he was— [DORAN: Not at all] wanted to see if whoever was gonna be in this job could look at a photograph. And that was—you know, that was what he could do. He could look at an artwork and see it and not just be thinking about could you use it?

CUNO: Yeah. And you got the job.

TREISMAN: I got the job, and two weeks later, Walter had a major brain aneurism and was in a coma for several months, and absent for quite some time, and then miraculously started to recover after that. And so we got to work together for four years, during which he was in charge of a lot of the art that ran in the magazine, and also in charge of introducing the artists, writing short essays about them. And Walter didn’t really like to write, as Ed said, Walter was a talker. He was—he was a speaker. He was someone who told stories. So that was what he did usually. He would speak, whether to Anne, who was working at the magazine, or to Jean Stein or to me, and I would take whatever he had said and make it into a written piece. And so that was how we started working together. And that was eventually how this book evolved.

CUNO: Yeah, so well, Anne, tell us how you met Walter.

DORAN: I met him in art school.

CUNO: Art school.

DORAN: Yeah, he’d been fired from the Corcoran, and I was going to the Corcoran School of Art a couple years later, and there was a lot of commotion at school. Walter Hopps was coming to school to look at the senior studios.

CUNO: ’Cause he was famous by then.

DORAN: Well, he was really famous— [she laughs] he was infamous.

CUNO: Yeah, yeah.

TREISMAN: Notorious.

DORAN: Notorious. And he—Walter, in those days, wore two pairs of glasses to look at art. Yeah, he never really—

CUNO: I mean, simultaneously he had two pairs on?

DORAN: [over Cuno] Yeah. Well, he wore one pair all the time, and then there was a second pair that went on to look—for close work. And he was tall and he had, well, two pair of glasses on. He scared me. [laughter] I mean, I was—he was a terrifying presence. And also because he didn’t say anything. He just stood there and looked at the work. And I didn’t say anything, he didn’t say anything, and his, you know, handlers sort of whisked him out of my studio.

He told me later he really liked the work, and he ended up being a real champion of it when I moved to New York later. But [Cuno: Yeah] that was how I first [she chuckles] encountered him.

CUNO: Yeah. So consistent with all of your recollections of Walter is a sense that he, as Ed described him, rhapsodized. And as Deborah talked about him as a storyteller. And in putting this book together, you guys had to work with his speaking. That was the basis of it. You recorded him, and then Deborah, who’s the fiction editor of The New Yorker, had to edit the text of the scripts from the recordings that you got. When did that all happen? When did the book start?

TREISMAN: We think it started around 2001.

CUNO: You think?

DORAN: They—

TREISMAN: It’s all a little fuzzy now.

DORAN: It’s all a little fuzzy now.

TREISMAN: No, we started talking about it in the late nineties. [Doran: Nineties] I had moved on to The New Yorker from Grand Street. And I had worked with Walter on a couple of art catalog essays that were longer projects, and just thought he has so many other things to say, and why are these things not being recorded? And why not tell the whole story? Let’s get it all done. And so Anne agreed to do the taping. Walter was in Houston at the time, and she would go down to Houston, [DORAN: Well—] and sit there and make him talk.

DORAN: [over Treisman] The important—the important part really is that Deborah got us a book contract…

CUNO: Yeah, yeah.

DORAN: …with Bloomsbury.

CUNO: Did the interviewing start at the beginning? Did you say, tell us about your family? Tell us about the birth, through the years—

DORAN: [over Cuno] Yeah, I tried to go chronologically.

TREISMAN: [over others] Anne tried. It’s nothing against Anne. Walter didn’t think chronologically. [she chuckles; DORAN: Yeah] So he would tell the stories that he most wanted to tell [DORAN: Mm-hm] in the beginning, and…

DORAN: Then we’d backtrack.

TREISMAN: …then everything—

DORAN: [over Treisman] Then we’d forward track.

TREISMAN: Anne would have to say, “Okay, but what about this? Why haven’t you talked about that? Why haven’t we thought about this?” And so there was a lot of kind of coaxing and managing to get to fill in the gaps in his stories. And the idea was that I would then take these tapes and come up with some sort of structure for making them into a book. And it wasn’t straight autobiography; he had artists he wanted to devote whole chapters to and—and so I was starting to work on that. And I’d gotten through, actually, really just doing his childhood, when he died in 2005. And so at that point, we no longer had this option, which I had always thought we would have, to have him go back and fill in gaps that he hadn’t covered and talk about the later years in his life and so on. That sort of explains why the book came out in 2017 when he died in 2005, because it took some time to recover from that setback, and then actually do it without him.

CUNO: Yeah. Yeah, I bet. So Ed, you heard some stories, probably not for the first time, reading this book. You probably were, in reading it, hearing him tell the stories that you had heard many, many times. But you must’ve heard stories that were new to you that he told. Did you know as much about his family life—that is, his parents and his grandparents and his grandfather, who goes to Mexico? And as I remember, he was a kind of a hardware store guy, and he was offered a chance to get 50% ownership on the export to Mexico of Coca-Cola.

DORAN: Coca-Cola.

CUNO: And he chose not to do that. Instead, he had a great idea, which was gonna be peanut butter tacos. [laughter]

DORAN: Yeah. Yeah.

CUNO: And it turned out peanut butter tacos didn’t work out so well. I mean, but to sort of—

DORAN: That was going to make the Hopps name.

CUNO: Yeah, didn’t happen. But so [laughter] was there a lot in this that you didn’t know? Or was he telling these stories his whole life?

RUSCHA: [over Cuno] There was a lot in this book I didn’t know. Like for instance, the city or town of Tampico, Mexico. And he apparently had a lotta connections to that through his family. And went back and forth. And we actually never called him Walter. We always called him Chico. And I read the book and—but I—was it clear in there how he got the name Chico?

TREISMAN: No.

RUSCHA: See? So that’s a mystery. [laughter]

TREISMAN: He never explained.

RUSCHA: There’s probably somebody in this crowd here—maybe Ed Moses or someone—that might know the origin of the name Chico. And then later on, people just started calling him Walter.

ED MOSES [in audience]: He thought Chico was too informal.

CUNO: Too informal. [laughter] Ed Moses says that Walter thought Chico was too informal. [laughter]

RUSCHA: Did it come from Chico Marx, maybe?

CUNO: So he talks a lot about his high school years. You put that together in the book so well. He talks about the girls, of course. But he also talks about music. And that was new to me, that he had so much involvement in music, everything from seeing and hearing Igor Stravinsky conduct his song of Dylan Thomas’s Do not go gentle into that good night, to seeing and hearing Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Billie Holiday. What was it like? What was he telling you about those years of his pursuit of music? And that precedes a kind of engagement with art.

DORAN: I think it was another world. Walter, wherever he was, he was there. The world of jazz in Southern California at that time was a world like the world of art in Southern California at that time. It was another world that he could enter into. He was so passionate about creativity and on a lot of different levels. It was just another entrancing group of people making entrancing things.

CUNO: Yeah.

TREISMAN: And in a way, it was his first experience of curating because he had this idea [DORAN: That’s true] with his college friend of booking music tours and bringing jazz musicians to campus, and he thought that would be his big success.

DORAN: There is a—there is a thread here about not making money in the family.

TREISMAN: Yeah. Yeah. [Cuno chuckles] That he thought that the jazz musicians [DORAN: There’s a through line to this story] would make all the money, and the artists would be impoverished. But what it says about him, I think, is that he heard this music that was wonderful to him and that he couldn’t—he kept—you know, he went way out of his way.

He joined the Kiwanis Youth Club so he could go to San Francisco and sneak off to jazz clubs. Because once he discovered something amazing, he wanted other people to hear it and appreciate it. So he wanted to book these shows. And that, I think, was his response to almost anything he admired, was, let’s get it to people. Let’s have other people see this and hear this.

DORAN: [over Treisman] Let’s organize it, let’s do something with it, let’s put on a show.

CUNO: About the same time, there was a program, when he was in high school, that took interested, talented students out to art spaces, including private collections like the Arensberg Collection. And he went to the Arensberg house. It’s where he first saw Duchamp’s work, for example, like that. And then he got invited back a number of times by the Arensbergs, because he was so engaging as a person, as a child, as a curious young person. Tell us about that.

DORAN: I think the Arensbergs were incredibly kind to him. He lied to his parents and told them that he was still doing whatever improving program he had been signed up for, but he was going to the Arensbergs once a week. And I do think it was his intelligence, his enthusiasm, his curiosity. And they were kind to him. They explained the art to him. They had wonderful art. It was a collection that was supposed to go to Philadelphia, I believe.

CUNO: UCLA. It ends up— [DORAN: Yeah. Yeah, it ended up—] ended up in Philadelphia, but it was supposed to go to UCLA at one time. They signed a contract for it, [DORAN: That’s right] and they were set to build a museum for it, but they never got the museum built.

DORAN: Yeah. This extraordinary collection of avant-garde art in California. And there is a really nice story in the book about how Mrs. Arensberg came upon him one day sort of patting a Brancusi. And Walter jumped back and was embarrassed, but she invited him to take the Brancusi to lunch, so he could have it on the lunch table and keep patting it and looking at it and—I think they were really good to him, and smong a few other people in California, were his real mentors in avant-garde art.

CUNO: And we’re assuming that everyone here knows of the Arensberg Collection, but maybe we should describe it more. Ed, did you see it when it was in the house?

RUSCHA: I never visited the Arensberg’s house, no. Is that what you mean?

CUNO: Yeah.

RUSCHA: But I believe that the house still stands where it did, which was up on North La Brea Avenue, and I think Walter spent a lotta time there. Walter was really quite aware of the expense that people would go to to buy artworks. And yet he, in his personal life, lacked the trait of being resourceful enough to make a living for himself. [DORAN: Like I said, there’s a thread…] Anything commercial was of no interest to him at all. So you couldn’t talk to him and say, hey, this dealer—I mean, I’m having trouble with this dealer. He wouldn’t care about that. He only cared about the art, and not about the commerce.

CUNO: Yeah. But the Arensbergs—a couple of things happened with that. That was the introduction to Surrealism and to sort of Duchamp and Magritte and de Chirico and Brancusi. So the kind of high modernist moments and that. But it also led to other galleries. There was a gallery that the artist named Copley had.

DORAN: Bill Copley had a gallery for six months.

CUNO: And he did six different exhibitions. Tell us about that.

DORAN: Yeah.

CUNO: And this is late fifties, so this is just about the time Ed’s coming to LA.

DORAN: There is a wonderful little booklet that Bill Copley put out. He was a great writer. His father was a newspaperman. He grew up in San Diego, I think.

CUNO: Bill Copley did?

DORAN: Yeah. And Bill came back, after a pretty bad war—he saw action in Europe—to write for his father. And his father was quite conservative and it didn’t really go well. And he had a drunken brother-in-law called John Ployart, who convinced Bill that they should show Surrealist art in Hollywood. And that didn’t go well either. [she laughs] But they had six great shows.

Bill became an artist because of that experience. But he also became a great collector. And that was the basis of his collection. The beginnings of his collection was he felt bad for the artists. In fact, I think he had guaranteed them a certain number of sales. So he bought [CUNO: Oh, really?] all the work [laughter] that didn’t sell. He bought like 150 Cornell boxes for, you know, fifty bucks each. [Cuno: Yeah] ’Cause he had told Cornell he would.

CUNO: Yeah. He talks about in the book, he talks about going to a Surrealist bookstore in West Hollywood, where he first saw books by Hans Bellmer, for example, and [DORAN: Yes] and Duchamp’s Green Box. And he bought for himself a green box, a Duchamp green box, as a birthday present, for twenty-five dollars.

TREISMAN: In a rather sneaky way.

CUNO: Yeah, tell us about that.

TREISMAN: Well, he had wandered into this bookstore. The bookstore was owned by—was it Mel Royer An assistant was there, who was sorting the contents of an estate sale. You know, sort of someone’s estate had been purchased in total, and it hadn’t yet been sorted out. And Walter happened to be there and noticed a copy of Duchamp’s Green Box. And I think it was maybe his seventeenth birthday or sixteenth birthday. He was really very young. And he said, “I’d like to buy this, and maybe I could just—” And she—the assistant—said, “Well, I don’t—you know, we haven’t even cataloged it yet.”

And he said, “Well, how ’bout I just write you a check for twenty-five dollars?” And she said, “Oh, alright, you know. That’s fine.” And later, he got a phone call, ’cause his phone number was on the check, from Mr. Royer, saying, “Well, happy birthday.” [laughter] “Congratulations,” you know.

CUNO: And then he was afraid that he was gonna have to return the [TREISMAN: Yeah] the box.

TREISMAN: No, he let him keep it.

CUNO: Let him keep the box, yeah. Now, Walter goes to Stanford first, before he transfers back to UCLA. And he goes to Stanford for all the reasons one might—because he was ambitious and the Bay Area was attractive to him, too. He chooses to go to UCLA, because he decides, big mistake, to refuse to take his parents’ money to pay the cost of going to Stanford, so he had to pay his own way back to UCLA. But he became very interested in the kind of north-south relations, the artists in San Francisco and the Bay Area, the artists in Los Angeles. And he puts together exhibitions that look at both of them and so forth. Ed, when you came, was there a clear sense in Los Angeles of the activity and action going on in San Francisco, and that that was a different kind of action going on in San Francisco?

RUSCHA: Well, that was like the early sixties. I just remember when Walter took this job at the Pasadena Art Museum. I mean, he had his naughty side, too. He took it upon himself to curate the shows, borrow all the works from these collectors around the Los Angeles area, and then take it upon himself to deliver those works back to the collectors.

And he did it in a sort of an unconventional way. And he hired this guy named Al Fox, who had a little step van truck with the words “Fresh Fish” [laughter] painted on the side. And so Al Fox, he was a radio DJ, and when he wasn’t working, he’d work for Walter. And so he’d have a Brancusi or something wrapped in a dog blanket, [laughter] bouncing around in this truck, and Walter’d just be happy that the thing finally reached its destination.

And [laughter] when Al couldn’t be reached, Joe Goode and I—Walter would hire us to do the same thing, except he’d lend us his Studebaker station wagon. And we would deliver valuable artworks around the LA area, like a Giacometti and Matisse sculpture, all wrapped in dog blankets. [laughter]

Anyway, everything happily came together. But Walter’s approach to that was very amusing but thorough. And as far as I know, he never got in trouble for it.

CUNO: Let me back up to 1952, which is when Walter rents a space off San Vicente and Brentwood to show Bay Area painting in Los Angeles. And he named that space after a man that his friend killed in a car accident. The man who died was named Maurice Syndell, and he called the gallery the Syndell Studio. If I remember correctly from the book, he called it that because he just kind of liked the magic of the name, Maurice Syndell. It wasn’t to honor the man who was killed. Or was it? Why did he choose to name it after the man who was killed?

TREISMAN: Well, he—

DORAN: He appreciated the creativity of the man.

TREISMAN: He appreciated the creativity of this story, which was…

CUNO: [over Treisman] Oh, the actual man, Maurice Syndell?

TREISMAN: …Maurice Syndell was a farmer, who decided to commit suicide, and probably had to wait on this road a really long time for a car to come along and hit him. And so Walter’s friend Jim Newman, with whom he’d done the music booking, was driving along, actually— And Jim Newman corrected the story that Walter had been telling for years, because Jim Newman wasn’t driving; his friend was driving.

And suddenly, you know, they’re going pretty fast on a long, flat road, and there’s a truck park. Suddenly someone dives out from in front of it and under the wheels of the car. And they—I mean, they had zero warning and no choice but to kill him. And this was his form of suicide. And I think Walter thought there was some creativity in that, and I think he thought that perhaps this man deserved to be an artist. So after that incident, Walter and some of his friends—I don’t know if you were involved in that; Kienholz was involved in it—started making works of art which were by Maurice Syndell, [laughter] and signing them Maurice Syndell.

And I think he took a lot of pleasure in the idea that someday, someone might write a dissertation on the work of Maurice Syndell. [DORAN: Maurice Syndell] And they made it particularly sort of grotesque and lewd and so on. And that was his way of letting this man free, I think, [laughter] you know? And so Syndell Studio was named after that man.

CUNO: And the studio lasts about three and a half years. But it’s there that he meets Kienholz, I think, or Kienholz and Berman come together at that studio?

TREISMAN: Yeah, he was working at Syndell. Kienholz was curating at Now Gallery. And so they crossed paths.

DORAN: He had met Berman in ’53. Walter had a one-person show of his own photographic work in the Coronet Louvre, which was a[n] art house movie theater that showed art in the lobby. And—

TREISMAN: [inaudible]

DORAN: He met Wallace Berman and Shirley Berman. They came to his opening there. And he got to be friends. He loved Wallace Berman’s work but Wallace didn’t wanna show at Syndell. So they were just friends for a long time.

CUNO: He didn’t want to show because he didn’t like the space, or because he didn’t like the reputation of the gallery?

DORAN: [over Cuno] He was a very retiring person. I think he didn’t necessarily wanna show at all.

CUNO: But it is there that Kienholz comes into the picture, is that right?

DORAN: [over Cuno] Yes, he does.

CUNO: And which ultimately leads to Ferus. So let’s [DORAN: That’s right] get to Ferus, the start of that Ferus Gallery.

DORAN: He gave Kienholz a show at Syndell. Maybe more than one, right?

TREISMAN: I think so, yeah.

DORAN: Anyway, they got to know each other and they had some art partnerships, a couple of Action shows and the All City Arts.

TREISMAN: The All City Art Festival.

CUNO: [over Treisman] Yeah, tell us about that. ’Cause that was a bit of a lark.

TREISMAN: Well, I think Kienholz was very resourceful when it came to getting assignments and [DORAN: Expert.] getting city money. And he had decided he would apply to run this All City Arts Festival. And he got a budget to do it in Barnsdall Park. And he asked Walter to do it with him. And for the first time, they were able to include work from commercial galleries, so they could show Syndell work there and Now Gallery work there. And throughout the process—I mean, they were allowed access to the sort of city storehouses of lumber and wire and whatever else they might need to set up this art fair.

So Kienholz, you know, was pulling this out and stashing it, I think, maybe at Syndell or somewhere else, [she chuckles] and preparing to create their own gallery somewhere with that money. He was also, I think, paying two dollars an hour to various poets, so that they could lie on the hillside and muse. And that, in a way, was working.

DORAN: In that show, they showed children’s art. They showed art they had made themselves. I think Maurice Syndell—

TREISMAN: Maurice Syndell had a [DORAN: Had works in that show] a very graphic nude [Cuno chuckles] with, I think…

DORAN: [over Treisman] Nasty works. [Cuno: Yeah]

TREISMAN: …like, wood shavings as pubic hair that…

DORAN: They showed everything.

TREISMAN: …was sort of outlawed at some point.

CUNO: Yeah.

DORAN: Yeah, it was a—Walter had a history of shows throughout his life, where they were just big and had everything in them. And I—in some ways, I always felt like Walter anticipated the internet, you know? He—it’s the first of many shows where he just sort of piled everything in.

CUNO: Okay, so let’s get to the Ferus, the start of the Ferus, and Ed, your early memories of the Ferus Gallery.

RUSCHA: When I met Walter, I don’t think he had anything to do with the Ferus Gallery. He was split from that.

CUNO: It was already—so Ferus II. It was on its way to Ferus II.

RUSCHA: [over Cuno] But he had had a long-term relationship with Wally Berman and George Herms and Moses and a lot of other people that began to show their work at the Ferus. But Walter was so unlike a gallery director, or at least somebody who would sell art, that I think he had limited interest in that. And he was more the other side. And so he really divorced himself from that gallery world and took on the museum, which was really interesting to see another side of him. And—

MOSES [in audience]: [inaudible]

CUNO: Everything was what?

DORAN: Made up.

CUNO: Everything was made up?

MOSES [in audience]: [inaudible]

CUNO: Oh, yeah? Ed Moses says that it was all lies; everything was made up, but— [laughter] But get us back to Ferus, [RUSCHA: Gotta…] and then the transition to Ferus II and the change when Irving Blum comes. So tell us about that history briefly. Any one of you.

TREISMAN: Well, the original Ferus was founded by Kienholz and Walter.

RUSCHA: Yeah.

TREISMAN: And they had—

DORAN: Made a contract.

TREISMAN: They made a contract there on the hotdog stand. They would be partners in art for five years. [she chuckles]

RUSCHA: Yeah.

TREISMAN: So they started Ferus together. And couldn’t sell anything, had some amazing shows, and it was a scene. But at a certain point, I think perhaps the artists expected to sell things. And Kienholz expected to be able to do his own work, which he was trying to do in the back of the gallery with, like, some mirror, so that he could see if someone came in at the front.

And Irving Blum appeared on the scene, and was everything that Walter and Kienholz weren’t, because he was a salesman. And he felt that the point of a gallery was to sell art. And so at around that time, Walter bought Ed Kienholz out. And I think to his dying day, Ed Kienholz felt that he hadn’t been properly paid, because Walter was supposed to return to him that Studebaker station wagon, which had become a lemon and had been passed along to some other poor artist. And so Ed never got his full payment, which was supposed to include the Studebaker. But—

RUSCHA: Oh, so that’s what happened to that Studebaker. [laughter]

TREISMAN: Yeah, yeah.

RUSCHA: Okay.

TREISMAN: So— [she chuckles]

RUSCHA: Now it’s beginning to piece together…

TREISMAN: And probably the dog blankets are still [RUSCHA: Yeah] in it somewhere. [laughter] So—

CUNO: [over Treisman] Well, we should probably point out that the image that we’re looking at on the screen behind us a portrait of Walter by Ed Kienholz from that time.

TREISMAN: Walter Hopps Hopps Hopps, [RUSCHA: Walter Hopps Hopps Hopps, yeah] in which he’s—instead of selling dirty postcards, he’s selling de Kooning. And other artists.

CUNO: [over Treisman] And it’s Hopp—tell us why it’s Hopps Hopps Hopps.

TREISMAN: Because he was Walter Wayne Hopps III. [CUNO: Right] And [laughter] things were always hopping around him. So he went into business with Irving Blum, and they managed to get investment from a wealthy patron of the arts, Sadie Moss, who kept the gallery running, and Irving kept the gallery running. But I think once it became commercially viable and once the narrowing down—winnowing down—of artists happened that needed to happen in order to make it commercially viable, it was no longer quite so interesting to Walter.

CUNO: But when Irving gets involved and there are more participation of East Coast artists, and one of them is Warhol, the famous exhibition of Warhol. We’ve got some sound of Walter describing Warhol in that exhibition—

TREISMAN: This was the last show at Ferus that Walter was involved with.

CUNO: [over Treisman] Yeah, so let’s hear the sound.

WALTER HOPPS [recording]: Warhol was fascinated, the idea of having a show in Hollywood, and the very first show of his Pop art was at the new Ferus Gallery. And the thirty-two original Campbell’s soup cans, which were part stencil and part hand-painted. And there were thirty-two of them, all different brands—kidney bean, tomato, pea, you name it. They were done in a very stylized, precise way, except the gold emblem, it’s just a round gold circle. He didn’t fill in all of the detail, the official Campbell’s logo, that you would see on the can. He simplified it. Subsequently, he did smaller versions, I mean, of canvases, where the soup can is smaller. And he did bigger ones. He did one with the label partially ripped off. He did all sorts of variations on it. But—he came west for that show. And that show was happening right when I went to the Pasadena Art Museum. And that’s the last show I had to do with in the new Ferus. But I remember talking with Andy about what did he—how did he—how would he describe the soup cans. They’re just in black and red and gold on a white canvas ground, centered up on both axes, just as simple as they could be. Alright. I asked him what he thought about it. And he gave me a funny smile and he said, “I think they’re portraits, don’t you?” I never asked him further what he meant by that.

[laughter]

CUNO: While he was doing his work at the Ferus Gallery, he was also advising collectors, and he was giving sort of seminars to young aspiring collectors. I remember Marcia Weisman, in the eighties, talking so fondly of those years with Walter, about when he would come and give these kind of seminars about these things. And one of the persons, though, one of the people that he was talking to a lot of the time and helping was Ed Janss. And tell us about that relationship and how important it was.

TREISMAN: Well, Ed Janss was someone whose family was—they were real estate moguls in LA. And Ed—he participated in that, but he was also—he had a love for contemporary art. And somehow he happened into Ferus at some point and happened onto Walter, and felt that Walter should be his guide to what was happening. And so they spent years going on trips together, going to see art, going to buy art. And Ed would put the money up for Walter to buy something and bring it back, and then sell it to someone in LA, whether it was himself or someone else. I think from the way that Walter talked about Janss, he was—he was really a father to him, in that way. He was the father who supported his interests, as opposed to the father who didn’t.

CUNO: Yeah. So at about this time—it’s 1959—Tom Leavitt was the director of the Pasadena Art Museum, and Walter began doing freelance work for him. Then in 1962, about the time that you’re driving around with the truck or the Studebaker for him, Leavitt hires Walter to be his curator, single curator, and registrar at the Pasadena Art Museum, which at the time was in the building that’s now the USC Pacific Asia Museum. And it was there that Walter organized various exhibitions—Motherwell, Joseph Cornell, Kurt Schwitters, Duchamp. A couple of questions: How did Walter scale up to that amount of activity, that amount of responsibility, going from the Ferus Gallery to something so substantial and with so much at risk and at stake? And what was the Pasadena Art Museum like, and the climate and the circumstances of Los Angeles at the time? Was it the place to go to for this kind of contemporary art?

RUSCHA: It was a big jump, huh, [laughter] from La Cienega Boulevard to the Pasadena Art Museum and places beyond. And then from there, of course—well, you’ll follow his chronology here. But it was stepped to bigger and bigger things. And while he was doing it, he was becoming more and more himself, which is a very enigmatic figure that was called upon to be responsible to his position.

And he began to see his position as being an independent person, and we all loved him for it because he didn’t play by the game. And he sort of made his own hours, ran by his own clock, and called people in the middle of the night for maybe nothing, just to talk. And the habits that he exhibited were hilarious but informative. And if you got off track in any way, or like, brought up some obscure person from art history, like, I don’t know, pull a name out—Augustus Vincent Tack. Well, now, he would be all over Augustus Vincent Tack [laughter] for you.

And you’d get a command performance. And so these command performances from this gentleman, he could do anything he wanted to do. I didn’t care if he showed up at the museum at the proper time or not. It didn’t matter to us. It’s just that Walter was always there, and Walter was Chico. [laughter]

TREISMAN: And he put you in your first museum show.

RUSCHA: Yeah, that’s right.

CUNO: [over Ruscha] Yeah, the New Painting of Common Objects show in 1962. And you did the poster for it, as I recall.

RUSCHA: Well, that came about probably at the last minute, because that’s the way he was. I think he began to be a little more responsible later on. But at the Pasadena Art Museum, he had these dreams that time would pass and he’d be pacing the floor, and with these ideas that eventually would fall into place. But he was bad at making catalogs, and he always dreamed about producing catalogs. And we were gonna make a catalog for that New Painting of Common Objects, and that thing never really came together. But I think there’s a prototype somewhere. And maybe Caroline Huber maybe has that in her archive of Walter’s. But said, “Well, at least let’s make a poster out of it.” And so I knew about this place called the Majestic Poster Press, and we called them and sort of gave them directions over the telephone. And we got a poster back in three or four days. And so at least we had a poster for the thing, but the catalog never really existed, which made it sort of delicious, in a way.

CUNO: [he chuckles] Well, you should describe the poster, because—and you went there and knew about it because these people made posters for, I don’t know, like boxing matches or something?

RUSCHA: Yeah. Yeah, circus posters and boxing matches and—and you could just tell them, “Use big type, make it big, make it loud, do it quick.”

CUNO: [he chuckles] So that was ’62. And about the time that’s about to open, Leavitt leaves the Pasadena Art Museum, and guess who takes his place—talking about scaling up now—to become the acting director of the Pasadena Art Museum but Walter. What was that moment like? How did he respond to those responsibilities?

TREISMAN: I know from going through a bit of the archive with Caroline, it’s just down on a square in the calendar. It’s like, “Pasadena.” Okay. [laughter]

DORAN: He’d met Duchamp first at the Arensbergs very briefly. And then he met him again in New York and they became quite friendly. And he wanted to do a retrospective of Duchamp’s work and—which hadn’t been done. He hadn’t had a museum show in America. And Duchamp was quite amenable to this, and he knew Pasadena really well. He’d had a girlfriend in Pasadena, apparently, and so he knew the Green Hotel, and he was kind of charmed by the idea that his first museum retrospective would be there. And so Walter just worked very closely with him to assemble that show, and it was a real, I think, labor of love for him. Partly because his first discovery of Duchamp had happened at age fifteen, in this situation of [CUNO: Of the Arensberg—] entering the Arensberg’s [CUNO: Yeah] house.

CUNO: Was it then that he hires Jim Demetrion to be his kind of assistant director or his chief curator?

DORAN: It’s around 1963.

TREISMAN: Yeah.

CUNO: So Jim was teaching at Pomona College.

DORAN: Pomona College, and he wasn’t a museum person, and I think there was a little resistance. Walter said, “I want you to be my chief curator.” And Jim was like, “I’m not really a museum person.” And I think Walter saw in him—Jim Demetrion ended up being a magnificent museum person.

CUNO: Fantastic, yeah.

DORAN: A fantastic museum person, first at Des Moines and then Hirshhorn.

CUNO: [over Doran] And then the Hirshhorn, yeah.

DORAN: But Walter really respected his eye. I don’t really know how they first met. But Walter also thought that he needed a backup. At that point, Walter’s addiction to methamphetamine had—was growing. And he wasn’t sure he was gonna last at Pasadena. He thought he might leave or be asked to leave. And he finally convinced Jim Demetrion, or so he says, to take the job of chief curator, by saying, “I may not be here forever, and I want it to be you. I’m picking you as my replacement now.”

CUNO: Yeah.

DORAN: And that actually came to pass, that Walter left and Jim became director eventually.

CUNO: Things happened rather quickly. I mean, that time, ’63 then, is the Duchamp exhibition; ’65 is Jasper Johns exhibition, Frank Stella. If he’s on speed as much as you said he was, he was enormously productive.

TREISMAN: Well, that was because he was on speed. [laughter] I mean, he was so productive.

DORAN: I can’t answer that.

TREISMAN: And also, you know, putting all of his assistants on speed. But he knew he was gonna crash and burn. And so he hit this point, I think, when the Cornell show was being worked on, ’67—or perhaps ’66—when he went on a trip to gather art, and came back and got off the plane in LA, and sat down in a chair and suddenly three hours had passed, and then another few hours had passed. And he called up a psychiatrist and basically said, “Come and get me.” So he was committed for a time. And that was the point where one board trustee, Harold Jurgensen, came to the hospital and said, “Can we send you an assistant? Can you work on the budget from here?” And he said, “Of course,” and did that. And Robert Rowan, who was not pleased with the situation, asked for his resignation. So Walter stepped down. Jim Demetrion became acting director. Walter was still helping to finish up the Cornell show. Jim Demetrion goes to get some Cornell works. In a taxi on the way to the airport, I think in Chicago—

CUNO: From the Bergman Collection.

TREISMAN: Yeah. He’s—I think he’d seen a specific collector, yeah. And the taxi goes off the ramp the wrong way, there’s a terrible accident. Jim’s thrown from the car, clutching one container of Cornell boxes. One is left in the car and burns. And Demetrion’s hospitalized, so Walter comes back to become acting-acting director, [she chuckles] while Demetrion’s in the hospital, and finish up this show. And that was his last show at Pasadena.

CUNO: But there’s somebody in Pasadena who sort of saves him again at that moment, by offering him like a fellowship in a think tank in Washington, DC.

TREISMAN: That was through Ed Janss, actually. He was out at Pasadena and he didn’t really know what to do, and Janss had some affiliation with the Institute for Policy Studies in DC, which was run by Marcus Raskin and Richard Barnet. It was a kind of left-wing political think tank. And Ed said, “Why don’t you go here for a year? Just do a fellowship here.” And Walter liked the idea. And he went and it gave him just a little space to see what was happening in DC. And while at the IPS, he got to know a philanthropic couple, Philip and Leni Stern. And Leni Stern was very involved in something called the Washington Gallery of Modern Art, which was—

CUNO: Which I’d never heard of before.

TREISMAN: Which was failing. And Walter had various ideas for how to save it, which culminated in not entirely saving it, but making it part of the Corcoran.

CUNO: Yeah, yeah. Ed, now we have a moment in which Walter leaves Southern California. And there must be a vacuum left, in part, by his departure, because of his great presence as a personality and as a museum professional and gallerist and a critic. So what was it like when he left? Did you feel that sense of loss?

RUSCHA: You know, he was one of us in many ways, and so he just became instantly absent, and that sort of left a hole in the whole scene. Especially if you would see him socially, and not be able to go to McGuire’s Saloon, out in Eagle Rock with him. And where’s Walter now? He’s in Washington, DC, I guess. And I know he had a life to live, and I seem to remember that he had a lot to do with the Dupont Circle in Washington.

CUNO: [over Ruscha] That’s where his gallery was, yeah.

TREISMAN: Yeah.

CUNO: There was some outpost of the Corcoran or some relationship to the Corcoran.

RUSCHA: Yeah. And so we lost touch with him, but we knew what he was doing. I mean, he was in the museum world back there. And we were always wondering how he was dealing with them, or rather how they were dealing with him and his peculiarities. But we didn’t hear any negative press or anything along the way, so he must’ve been doing alright.

CUNO: Yeah. Well, there was a great story, ’cause he was there during the March on the Pentagon in the anti-war era. And you’ll recall that among other things, a number of people—Ginsberg and some Yippies—want to elevate the Pentagon, by sitting down and meditating and making it rise. And there’s this all kind of crazy activity. Well, he’s there at the time and he’s opposed to the war and intrigued by the opportunity with this mass demonstration, to do something. And he had a spray can, paint can. I guess he was gonna be spraying some sort of thing. But he had to go back for a meeting. Tell us that story.

TREISMAN: [over Cuno] Well, he was going to—he’d brought along some cans of black spray paint because he decided he wasn’t gonna write anything, he was just gonna spray blackness on the Pentagon and that would be his form of protest. And at some point, the police come. And Walter says, “I’ve got a board meeting at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art, and I can’t miss that.” So he ducks in the bushes, waits for the police to pass him by, and then he runs off to his meeting. Which just seems very typical of the kind of—not schizophrenic, but multivalent person he was.

CUNO: Yeah. Now, running out of time, so we should move along quickly. Just to give everyone a sense of this, in 1967 he’s appointed director of this gallery, the Washington Gallery of Modern Art. Two years later, he’s acting director of the Corcoran Gallery. Then a year after that, he’s director of the Corcoran. Then a year after that, he was named U.S. Commissioner for the Venice Biennale. And it was while he was in Venice that he received a call from a reporter at the Washington Post, asking him if he wanted to comment on his dismissal from the Corcoran, which was the first time that Walter had heard he’d been dismissed from the Corcoran. And then he was saved, at that moment, by an old friend of his who was a teacher at the University of Chicago at the time, Joshua Taylor, who was head of the National Collection of Fine Arts, offers him a job and he takes it. This kind of spinning—you can just feel a sense of spinning out of control.

TREISMAN: Well, or…

CUNO: And landing on his feet.

TREISMAN: …just along. [they laugh] Spinning along.

CUNO: And it was at that time that those who worked with him—as Ed has described him, always late—grew tired of his being late. and also it was kind of funny, and made a pin. And it happens that we had three such pins. Each of you have one of these. Tell us what the pin says.

TREISMAN: It says, “Walter Hopps will be here in twenty minutes.” [laughter]

CUNO: Yeah, yeah. So all this kind of crazy, antic activity was going on in extraordinarily important places. But the one thing that seemed to be—really save him, where there was a kind of a soulmate, was when the de Menils hired him on as an advisor, as they’re beginning to build their collection and thinking about a museum and ultimately, building the museum. Tell us about that transition to the Menil Collection.

DORAN: I think that Jean de Menil had already died. Before Mrs. de Menil thought about building the museum. And I’m not sure how they met. Do you know, Deborah?

TREISMAN: They met in New York. He’d met John— [DORAN: In New York] John de Menil in New York; he hadn’t met Dominique.

DORAN: But they had an extraordinary collection of art that spanned centuries and styles. Their art advisor was a Jesuit priest, which may account for the fact that the art itself all has a kind of quality about it, whether it’s Byzantine icons or Surrealist art. In the early eighties, she had started to talk to Walter about building a museum for this collection that she had put together for her husband, and he was commuting between Washington, where he was living, and Houston, for a few years. And he would stay with Mrs. de Menil in her son’s room, Francois—

CUNO: [over Doran] Yeah, the Philip Johnson-designed house.

DORAN: In the Philip Johnson house, and worked down there. And she really was, I think, the first person that gave Walter carte blanche to do the museum that he had always wanted to build and run.

CUNO: So it’s both in building the collection and in building the building, working with these two extraordinary people, Mrs. de Menil for the collection, and Renzo Piano [DORAN: Renzo Piano, the architect] for the building. And then installing it in the most beautifully installed way. It was the kind of culmination. But he continued working with them for quite a number of years, writing—well, speaking catalogs, evidently, that Deborah was editing into written texts. But he dies twelve years ago now. He dies in 2005.

TREISMAN: [over Cuno] 2005, yeah.

CUNO: What did he die from?

TREISMAN: He had pneumonia and heart failure.

DORAN: Pneumonia. He—we had been all here, Walter and George Herms, were having a dialogue, and I was moderating. And it was a great time. It was a great dialogue, and Walter and Caroline, his wife, stayed on for a few more days, and Walter fell ill here.

CUNO: And he’s buried in the high desert in Lone Pine, in a simple pine box with a telephone. [laughter]

RUSCHA: Designed by Richard Jackson.

CUNO: Oh. [chuckles]

DORAN: The artist Richard Jackson, yeah.

CUNO: What was designed, the box or the phone or both?

RUSCHA: The box [DORAN: The door] or the phone?

CUNO: It was a door from his studio or something.

RUSCHA: Or I think we were just told that there was a phone in there, but the lid was a door from his house. And that was the lid of the casket.

CUNO: Yeah. [he chuckles]

DORAN: And the Reverend George Herms, who’s here tonight, [CUNO: Yeah] gave the eulogy.

CUNO: Oh, yeah? Now, I want to ask you each one last question, but I want to flip to the last image, because this will show you the gang. There’s Ed Moses, pointing up, looking like a figure out of a Raphael there. Pointing up at Walter, arms crossed, glasses on. Over his right shoulder, Jim Rosenquist; over his left shoulder, Bob Rauschenberg. Dennis Hopper’s up there. Ed Ruscha’s got a drink in his hand, at the far right. [laughter]

Now, for each of you, just reflect about the legacy of Walter and what is has meant to you as a person and a professional. And let’s begin with Ed, and go to Anne and Deborah.

RUSCHA: Well, you can look at this picture here and you can see a dominant figure. And it just happens to be Walter Hopps. I mean, there he is. And that’s the way he was in real life. As somebody who really commands attention from even the silence that he can give you. And then once he spoke, it was sort of miraculous, and not something that you would easily forget.

CUNO: Yeah. Anne?

DORAN: Generosity. He was incredibly generous. Both with artists, and as Deborah said—I mean, if he saw something that he liked, whether it was music or art, he was a fan. There’s a generosity to fans. A real fan wants everyone to see what they see. And for me, I benefitted twice from him. He was incredibly supportive of my art. He was always supportive of artists. He was like an artist himself. But also as a—he was a mentor of mine in looking at art. And he was a brilliant teacher. He just gave and gave. He was the most generous person I’ve ever met.

CUNO: Oh. Deborah?

TREISMAN: Well, I think there are two sort of qualities that stay, that stay through his words. And one was just excitement and almost glee with which he would greet art that he hadn’t seen before, that was doing something. That he could see what it was doing. And how amazing, you know? Having listened to a hundred hours of him talking about art, I think amazing was the word that was spoken the most. [she chuckles] And art did not stop amazing this man, throughout his entire life. Confronted with creativity of others, he was amazed. And when Calvin Tomkins profiled him for The New Yorker in 1991, there’s a moment in the piece where Tomkins asks him, you know, “Do you consider yourself an artist? Or is what you do enough?” And Walter had this wonderful response. He said, “I feel like I come from a tradition that’s 25,000 years old, where, you know, there’s the cave artist who’s doing the painting; but someone had to find the cave. Someone had to mix the pigments. Someone has to stand there and hold the torch while the artist does it.” And he said, “I’m holding the torch. And that’s close enough.” And so that, for me, is just—that captures what was special about him.

CUNO: Yeah. Well, ladies and gentlemen, Ed Ruscha, Anne Doran, Deborah Treisman. The book is called The Dream Colony: The World of Walter Hopps [read: A Life in Art].

[applause]

Our theme music comes from “The Dharma at Big Sur,” composed by John Adams for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. It is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts or Google Play Music. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts. Thanks for listening.

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

DEBORAH TREISMAN: “Someone had to find the cave. Someone had to mix the pigments. Someone ...

Music Credits

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.