Ernest Shackleton’s 1908 Nimrod expedition base, Cape Royds. © Antarctic Heritage Trust, nzaht.org

“The last view of civilization, the last sight of fields, and trees, and flowers, had come and gone on Christmas Eve, 1901, and as the night fell, the blue outline of friendly New Zealand was lost to us in the northern twilight.” —Captain Robert F. Scott, The Voyage of the Discovery, vol. 1, 1905

In December of 1901, Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s National Antarctic Expedition sailed aboard the three-masted Discovery toward the largely unexplored continent of Antarctica. With its flock of sheep bleating in terror and its 23 dogs howling with excitement, the Discovery expedition began its ambitious journey to find the South Pole and claim its place in the history of Antarctic exploration. At the turn of the last century, Antarctica was among the last unexplored regions on Earth, and from the few accounts that existed, all that was known for certain was the harshness and violence of its climate and landscape.

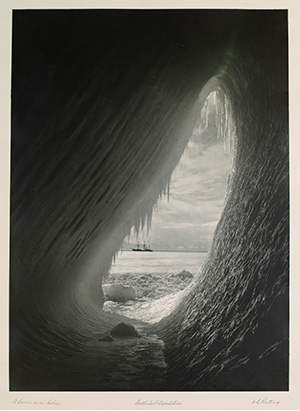

A Cavern in an Iceberg, Herbert George Ponting, from the portfolio Scott’s Last Expedition, The British Antarctic Expedition, ca. 1910–13. Transferred from the British Museum. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Scott’s 1901 expedition was only the second ever to winter on the Antarctic mainland; it was a pivotal event during what has since become known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, a brief span of just 22 years so called for its tales of extraordinary bravery and perseverance, for epic tragedy, and for pioneering scientific discoveries. Today, over a century after Scott forced the Discovery through pack-ice to establish its base camp, conservation specialists, under the guidance of New Zealand’s Antarctic Heritage Trust and its partners, are fulfilling a mission to preserve historic landmarks and artifacts from these early 20th-century sites.

Captain Scott’s 1902 Discovery expedition base, Hut Point. © Antarctic Heritage Trust, nzaht.org

As it began the development of long-term preservation solutions for the most significant sites under its care, the Antarctic Heritage Trust (AHT) approached the Getty Foundation about an architectural conservation grant. Initial funding in 2002 supported conservation assessments and recommendations for several historic sites, including the Discovery and Terra Nova huts from Scott’s 1901–04 and 1910–13 expeditions. Two subsequent grants in 2004 and 2007 funded the implementation of conservation work on the Terra Nova hut at Cape Evans and Ernest Shackleton’s 1908 hut at Cape Royds. While these were unusual grants for the Foundation, its advisory committee believed that the projects offered a unique opportunity to complete groundbreaking research for the international conservation community that could be applied to the preservation of other buildings and materials in extremely cold climates or remote locations. The huts were ideal subjects for this research because the sites and their contents had survived fairly intact. (The most famous item to be unearthed in recent years is, of course, Shackleton’s whiskey stash; it has been carefully thawed and conserved, and after scientific analysis, the blend has even been recreated by the original distiller in Scotland!)

Each successive expedition to Antarctica—then and now—has faced the challenge of working in the hostile polar environment. At Discovery’s base, for instance, Scott’s crew survived the extreme conditions while carrying out research experiments in the exceedingly cold auxiliary huts that housed their scientific equipment. Today conditions are similarly difficult, yet the AHT maintains a conservation presence around the huts year-round. Their work follows the same schedules that dictated the lives of the early explorers: during the long winter when the average temperature is -30°F (-34.44°C), conservators work on preserving artifacts at New Zealand’s Scott Base, a governmental science facility at Hut Point, leaving field work for the summer window of December to January with its extensive daylight and tolerable temperature range of 5°F (-15°C) to 21°F (-6°C).

Accommodations of the Trust conservation team, Cape Evans, 2004. © Antarctic Heritage Trust/F. Wills

From the outset, the AHT knew that managing tourism in such an inhospitable environment would be less of an issue than providing access to the landmarks by other means. One very successful solution to the access problem is the Antarctic conservation blog hosted by the National History Museum, London, which allows anyone to join the conservators in situ as they share their ongoing work. A second solution, which is producing stunning images, is the partnership of the AHT with Google’s Antarctic street views and World Wonders site; they have worked together to create panoramic views of the South Pole, as well as exterior and interior views of the huts at Cape Royds and Cape Evans.

As you explore Scott’s Hut, you cannot help but recall that this was the point of departure for his final and tragic journey to the Pole. While Scott reached his prize at last with four others, they arrived in early 1912 only to discover that the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen had beaten them there by a month. Bad fortune and worse weather dogged their return, and all five eventually froze to death on Ross Ice Shelf in March. With the perspective afforded by a century’s worth of distance and despite some of the less admirable aspects of the Heroic age, I find it difficult not to admire and envy the profound self-assurance and optimism—and streak of madness—possessed by these individuals who set off in search of the unknown and who never seemed to doubt the achievability of their goals even in the face of incredible hardships and possible death.

Today it is reassuring to know that a bit of holiday warmth extended to the frozen ends of the earth more than a century ago as Scott and his crew enthusiastically passed what would be their last festive Christmas celebration together:

“A merry evening has just concluded. We had an excellent dinner; tomato soup, penguin breast stewed as an entree, roast beef, plum-pudding, and mince pies, asparagus, champagne, port and liqueurs–a festive menu. Dinner began at 6 and ended at 7. For five hours the company has been sitting round the table singing lustily; we haven’t much talent, but everyone has contributed more or less, and the choruses are deafening.” —Captain Robert F. Scott, Scott’s Last Expedition, vol. 1, 1914

Scott’s Last Expedition. The Castle Berg, 1910, Herbert George Ponting. Transferred from the British Museum. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Comments on this post are now closed.