From mosaics to embroidery, curators of Heaven and Earth at the Getty and the National Gallery pick the artworks they find most unforgettable

Exhibition banner for Heaven and Earth flying high at the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Movies have directors; museums have curators. In planning an exhibition, curators control the final picture, dramatically shaping what a visitor experiences.

The exhibition Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections was “directed” by two American curators, Susan Arensberg and Mary Louise Hart, in partnership with Greek curators from the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports and the Benaki Museum in Athens. Susan and Mary have interacted with these objects as few others have done, getting the chance to study them in great detail. I wanted to know which of the over 150 objects in the exhibition these curators found the most interesting and magical—and they shared their selections with me.

More Than Meets the Eye

Susan Arensberg, who curated the presentation of Heaven and Earth at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. (October 6, 2013–March 2, 2014), chose three objects as particular favorites. All are ones that, with close looking, reveal more than first meets the eye.

Mosaic Icon with the Virgin and Child, late 1200s, made in Constantinople. Glass and gold tesserae on wood, 42 1/8 x 28 15/16 in., 88.184 lb. Image courtesy of the Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens, inv. no 990

One of these is the mosaic icon of the Virgin Episkepsis, which possesses exquisite materials and artistry. In Susan’s words:

Less than a dozen large mosaic icons survive, so this is a great rarity. The mosaic technique was known in antiquity but reached its height in Byzantium. Byzantine mosaics are much subtler in technique and make use of small cubes, or tesserae made of marble, mother-of-pearl, colored glass, and gold and silver leaf. Byzantine mosaicists used such materials to create figural compositions of great complexity and expressive power. They often inserted irregularly sized tesserae, especially those of gold and silver, at different angles to catch and reflect the light to create a sparkling, otherworldly atmosphere. In this icon, the artist used the largest tesserae for the background, smaller ones for the drapery shot with golden highlights, and still smaller tesserae for the flesh tones. With tiny marble chips in shades of ivory, cream, and pink, he created the Virgin’s tender, rather melancholy expression, suggesting that she foresees the fate of her son.

Susan also pointed out another particularly fascinating work: the small golden pectoral cross of Georgios Varangopoulos, which was worn around the neck. Its front is adorned with lapis lazuli, possibly imported from Afghanistan, the major source for that stone. The cross is unusual, Susan pointed out, because it is inscribed with the owner’s name: the back bears an inscription stating that it was made for Georgios Varangopoulos.

Pectoral Cross (front and back), A.D. 1200–1400. Gold and lapis lazuli, 1 9/16 in. high. Benaki Museum, Athens. The inscription on the back states, “May my cross become a weapon and guardian for Georgios Varangopoulos Sebastos.” Image courtesy of the Benaki Museum, Athens, inv. no. 1853. Photo © Benaki Museum, Athens

“That name suggests that he was a ‘Varangian,’” Susan said, “which was the Byzantine name for Anglo-Saxon or Scandinavian mercenaries who served in the Byzantine army. So you have a cross with lapis from the East, made for a Western European, and the two meet in Byzantium. Although a small, private work, this cross is emblematic of Byzantium’s cosmopolitan nature.”

Icon with the Monogram JHS, 1450–1500, Andreas Ritzos. Egg tempera and gold on wood, 17 1/2 x 25 in. Image courtesy of the Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens, inv. no BXM 1549

Yet another particularly special work of art, said Susan, is the painted Byzantine icon with the inscription JHS. The bold letters draw the eye, standing out sharply against the gold background. A closer look reveals something more, however: “within the letters JH is a scene of the Crucifixion, with Christ the Savior on the cross,” Susan pointed out, “and within the S, two scenes of the Resurrection. The artist cleverly depicted images that communicate the meaning of the letters JHS, which can stand for either the first three letters of Jesus’ name in Greek of for the emblem J(esus) H(ominum) S(alvator), or Jesus Savior of Men.”

Emotion in Needle and Thread

Mary Louise Hart, curator of the presentation of Heaven and Earth at the Getty Villa, pointed out several more objects worthy of a special look—in particular this liturgical cloth, which she named as a personal favorite.

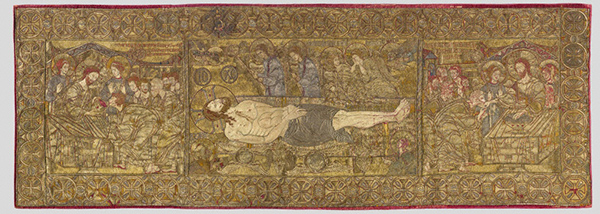

Liturgical Cloth (The Thessaloniki Epitaphios), about 1300, made in Thessaloniki, Greece. Silk and linen, 25 x 70 1/2 in. Image courtesy of the Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki

A specialist in theater, Mary was drawn to the threadwork, emotion, and characters in this magnificent object, describing it as follows:

What stands out most is the extraordinary expression of emotion the embroiderers were able to achieve with needle and thread—typically a medium that presents forms more stiffly. This is even more pronounced with the inclusion of gold and silver wire wrapped around the silk thread. The expression of human emotion carries the religious content and meaning. And the variety of angels, of course, is fabulous. There is drama within this cloth, and drama surrounding it: this cloth is located in what is arguably the most potent religious and emotional space in the exhibition, between the Palaeologan Crucifixion, the icon of the Pantokrator from St. Sophia in Thessaloniki, the Virgin Episkepsis from Constantinople, and the Man of Sorrows from Kastoria. Many themes can be articulated through this core arrangement: Palaeologan iconography, the art of Thessaloniki, mosaics compared to icons, Orthodox iconography.

The Thessaloniki Epitaphios (foreground, in case) anchors a dynamic arrangement of Byzantine icons in the exhibition.

Textiles have often been overshadowed by other art forms that have survived the centuries in better condition and in higher numbers. Recent scholarship and exhibitions are effectively closing that gap, but few examples are left from antiquity, making this one all the more significant.

When the Getty team unpacked the Byzantine liturgical cloth, Mary said, they were all amazed by the detailed embroidery. In the Getty Villa exhibition, the red wall color brings out the gold and red colors even more intensely. Don’t miss it, or the glittering selections Susan named, when you visit the exhibition.

What is your favorite artwork from the exhibition Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections?

_______

Thanks to Mary Louise Hart and Susan Arensberg for their time in answering my questions. Mary is associate curator of antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum and a specialist in ancient myth, epic, and theater. Susan is head of the Department of Exhibition Programs at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Text of this post © Ashton Prigge. All rights reserved.

My favorite is the Fragment of a Wall Mosaic from the Church of Archairopoietros in Thessaloniki. The blue and green acanthus leaves float above a fountain that seems to be spilling over onto the earth and the the viewer gets a special treat if they crouch down in front of it and see the SPARKLING gold background. One feels transported to the Basilica in AD 450, marveling at this heavenly creation, dazzled by the artistry and contemplating what it meant to the people of Thessaloniki at that time.