Rutger Hauer as Roy Batty in Blade Runner, 1982. Courtesy of and © The Blade Runner Partnership | © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Los Angeles, summer 2013: Still no flying cars in sight.

Even if you’re not familiar with Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), rest assured you’ve already seen some version of its world. If not in the countless bastardized sci-fi films that came after, then possibly—flying-car expectations aside—outside a major downtown window on a hazy night. If you have seen the future according to Blade Runner, then you know that, despite piles of commentary 30 years on, the film’s many [spoiler alert] themes, and the philosophy-laced conversations they stir up, remain enjoyable and relevant. The Blade Runner world owes much to Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, a main catalyst for the film.

“Whether it be its narrative fatalism or its haunting evocation of its urban setting, a multicultural techno-grunge hellhole drenched in rain, infested with advertising and shrouded in mist, the film continues to be the mother of modern sci-fi, blending disparate genres with philosophical queries.” —Nick Schager, Slant

So, what is the future according to Blade Runner? It’s the neo(n)-noir, cyberpunk Los Angeles of 2019. It’s ramen noodles in the street, under smoky lights, elbow to elbow with the ones left behind. It’s a cabaret where neither the dancer nor the snake around her neck is considered real. A cityscape of darkness and LEDs, where the distance between top and bottom is the most pronounced feature. It’s detective Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) on the hunt for escaped replicants (androids)—an increasingly ambiguous task of distinguishing between human and non-human. A task that leads Deckard to love, and viewers to question their own humanity.

Blade Runner has a lot to offer the inner geek. I could go on about Edward James Olmos’s origami unicorn folding skills, or why the final cut of the film is indeed the best version, or why replicant Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) is the true hero. But, while we still bask in the glow of Pacific Standard Time Presents: Modern Architecture in L.A., it’s worth another look at the film’s relation to architecture and environment. Also, we’re screening a copy (DVD) of Blade Runner: The Final Cut tonight as part of the Getty Center’s Friday Flights, with only a couple days left to catch Overdrive: L.A. Constructs the Future.

By the way, I’m pleased to say that this is not the first time we’ve mentioned Blade Runner, however briefly, and movie locations on The Iris.

Of Futures Past

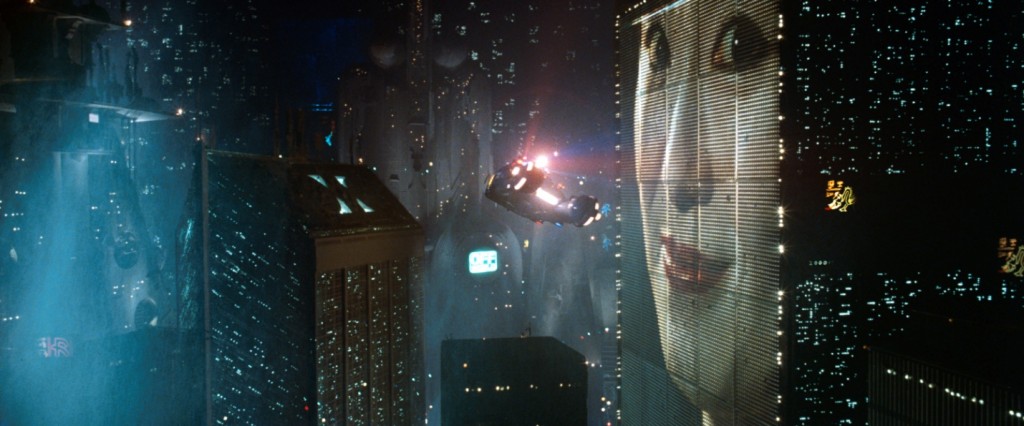

Flying above the city in Blade Runner, 1982. Courtesy of and © The Blade Runner Partnership | © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Blade Runner‘s alternate, nebulous, and extremely dense Los Angeles may not match up exactly with today’s L.A.—though I always wonder which L.A. I’m in when driving down the 405 by the Wilmington refinery at night—but its genius lies in the buildings chosen to highlight the future. A future that, from the day the film premiered, already looked worn. Retrofitted by necessity.

Left: Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) walks in front of downtown’s Million Dollar Theater. Right: Union Station as police headquarters in Blade Runner, 1982. Both images courtesy of and © The Blade Runner Partnership | © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Rick Deckard’s apartment in Blade Runner, 1982. Courtesy of and © The Blade Runner Partnership | © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Amusingly, given that the Overdrive exhibition celebrates architecture between 1940 and 1990, all of the iconic structures in the film were built before 1940: Bradbury Building (built 1893); Million Dollar Theater (built 1917); 2nd Street Tunnel (opened 1924); Ennis House (built 1924); and Union Station (opened 1939). The Bradbury Building plays the most prominent role, serving as the warehouse-like home of genetic designer J. F. Sebastian (William Sanderson) and stage for the film’s final showdown. What I wouldn’t give to have the Bradbury Building all to myself, even the dystopian version. Los Angeles Union Station is, somewhat predictably, police headquarters, while the Million Dollar Theater will apparently be hosting Los Mimilocos and Mazacote Orquesta in November 2019 (plan ahead). As for Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House, it doesn’t so much appear in the film as have its ancient Mayan-inspired textile blocks appropriated for Deckard’s apartment.

Seeing those buildings in the Blade Runner universe is great, but the most iconic, “ancient” building in the film has never actually existed: the Tyrell Corporation building, a symbol of power and hubris so great it had no choice but to hint back to ancient pyramids. If any American city could actually pull this building off, it would be Los Angeles.

Of Futures Present

Flying police car in futuristic L.A., Blade Runner, 1982. Courtesy of and © The Blade Runner Partnership | © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Since Blade Runner’s release, its version of Los Angeles has become an increasingly familiar place—but not because that place is Los Angeles. Among Ridley Scott’s set design directions were the words “Hong Kong on a bad day,” but, based on the photos coming out of China this year, it’s now more like “Beijing on an average day.” The future is now, of course.

Smog-obscured Pangu Plaza Office Building, Beijing, January 14, 2013. © ChinaFotoPress/Zuma Press

LEFT: Smog-obscured CCTV Headquarters, Beijing, January 14, 2013. © ChinaFotoPress/Zuma Press RIGHT: Still from Guillermo del Toro’s Pacific Rim, 2013. © Warner Bros. Pictures

Dystopian issues—overpopulation, extinction, pollution, climate change—once presented as futuristic, are now our starting point. We see it in the news, but I’m also curious to see what the latest sci-fi movie has to say about our new realities and possible futures. Most recently, I watched Guillermo del Toro’s Pacific Rim (2013), in which his Hong Kong 2020 is virtually indistinguishable from Blade Runner’s Los Angeles 2019. Might the future then be Elysium’s (2013) Earth 2154?

More Human than Human

Come watch Blade Runner with us and you’ll have even more timeless worries to wrap your head around, like: your own mortality; the future of human identity; and whether or not, if you ever witness attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion, the future version of Instagram will be enough to keep your memories from washing away, like tears in rain.

Seriously: come on up, see three different versions of Los Angeles—on the screen, in the gallery, and in real life—and dress up like Daryl Hannah’s Pris to make the most of Friday Flights’ neon, New Wave 1980s events.

On view in Overdrive: PA and PE, 1990. Peter Alexander. Acrylic and oil on canvas. Courtesy of Pacific Enterprises. © Peter Alexander

Then dream of a future L.A.—possibly one with electric hover cars, where unicorns roam free in the Santa Monica Mountains.

Comments on this post are now closed.