Arches of the Dodd Building (Southwest Front Avenue and Ankeny Street), Portland, Oregon, 1938, Minor White. Gelatin silver print, 13 3/16 x 10 5/16 in. Portland Art Museum, Fine Arts Program, Public Buildings Service, U.S. General Services Administration

As the curator of the

Los Angeles LGBT Center’s Advocate & Gochis Galleries, in July I co-hosted an LGBT reception at the Getty Center for the current exhibitions on Minor White and Yvonne Rainer. The Minor White exhibit, in particular, was quite a hit with those in attendance. Why? The overwhelming response was that the wall text, with numerous references to White’s status as a closeted gay man, was not only interesting but also inspired a deep connection to the artwork. They were surprised and impressed with this holistic approach in such a major art institution and found the treatment of the subject very exciting!

As the curator of a gallery connected to the world’s oldest and largest LGBT organization, I’m often asked to justify the need for a gallery that exclusively features work by queer, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) artists. Aren’t they just artists? Shouldn’t we try to support queer artists by legitimizing them beyond their queerness? Should an artist’s sexuality even be a part of the academic and public dialogue? If an artist’s work is not explicitly queer in content, does it matter if he or she is LGBT-identified?

Yes, yes, yes, and yes.

The Civil Rights Movements of the past 60 years have not quite taken us to Utopia, and it is important to remember our struggles and celebrate our differences to remind ourselves, particularly in the United States, that we still have far to go. We need spaces for dialogue, processing, and action; lumping all the colors of the rainbow together leads to a dull and stagnant society. There is often a fine line between acceptance and assimilation that leads some to argue for blending in, but that never solves the underlying issues.

In many cases, artists’ sexuality may not seem important to an interpretation of their work, particularly if that work does not explicitly address sexuality. But without this context, we miss rich and intimate aspects of a piece that can have profound impact not just on its interpretation, but also on the very writing of history itself. Neglecting this aspect of an artist’s perspective skews history and deletes context.

This is true with artists of the past, too. Even with artists who were not out during their lifetimes, there is much we can learn about the queer experience from their work—and thus about the arc of humanity.

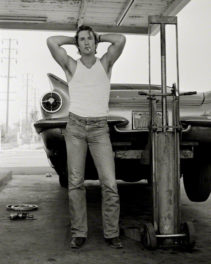

Take, for instance,

Minor White. If you remove the queer context from an analysis of his work, you still get to look at beautifully constructed photographs. But include this aspect in the dialogue, and you get a very different picture. Understanding that he was a closeted gay man gives new dimensions to pieces such as

Arches of the Dodd Building, at the top of this post.

At first you may just see an anonymous man standing in front of a building, a photo taken for an early assignment. Know a little about White’s backstory, however, and you now see a man cruising for sex in an area known for being a gay cruising spot. You see not just nicely framed nature images, but intimate commentaries, such as in

Point Lobos, California, also called

Two Waves and Pitted Rock. In this you suddenly see the pain and struggle to align the inner self with the constraints of a postwar society, so unwelcoming to the queer person. You see White's spiritual journey through his photography as not just a religious exercise, but also as a therapeutic one.

Point Lobos, California, 1952, Minor White. Gelatin silver print, 7 3/16 x 9 3/16 in. The Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum, bequest of Minor White. © Trustees of Princeton University

For many decades, the queer sides of artists were systematically erased from the dialogue in museums and galleries. Sometimes this was a function of survival on the part of the artist, as it was for Minor White, but often it was simply the conservative framework of art institutions themselves. I believe it is our moral imperative to uncover these hidden storylines and expose the full picture both for the sake of these artists, many of whom suffered greatly during their lifetime as a result of their sexuality, and for the truer writing of history.

We still need LGBT-specific exhibition spaces. In addition to keeping the conversation going, they serve as important venues for experimentation and provide opportunities for up-and-coming queer artists. Until all major, established art institutions fully include an artist’s sexuality in the discourse, there will be a desperate need for LGBT-specific exhibition spaces. Even as our society becomes ever more integrated and friendly toward those outside the accepted mainstream, sexual and otherwise, we stand to lose so much of our human history by neglecting queer storylines for the sake of assimilation. Gaining mainstream recognition of queer artists and documenting their stories in major art institutions is essential to soothe the wounds inflicted upon LGBT artists of the past and present. The real healing will come when all queer artists are recognized as queer no matter where their work is shown.

Hats off to curator Paul Martineau and to the Getty for organizing such an

insightful and comprehensive exhibition, adding to the greater discourse and brilliantly illuminating the many facets of White’s life and work.

Text of this post © Katie Poltz. All rights reserved.

Thank you, Katie, for sharing this thoughtful, articulate critique! Really thought-provoking! Reminds me of pieces I’ve read or seen recently about the double-edged sword of the younger ones in the millennial generation proclaiming that we live in a post-racial society. It’s great that the culture in general is more accepting of racial (and sexual) minorities, BUT sometimes that glosses over the fact that there are still systemic issues not fully dealt with and that those aspects of identity for individuals still need to be acknowledged fully, especially in something as intimate as the creative process. Will definitely try to get out and see the MW exhibit before it closes.