The recently acquired white-ground lekythos on display in Women and Children in Antiquity (Gallery 207) at the Getty Villa is a handsome addition to the Museum’s antiquities collection.

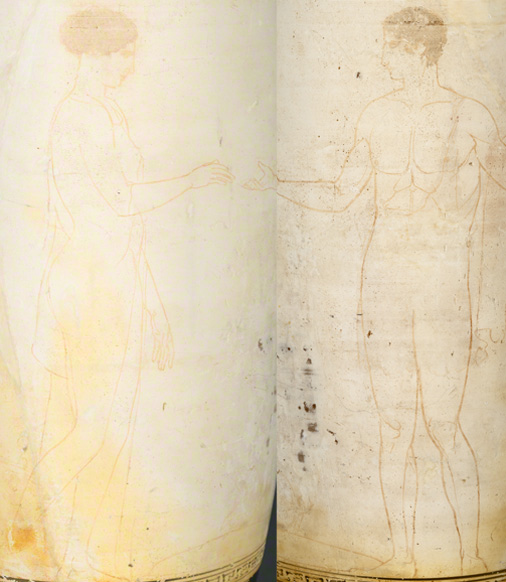

Oil jar (lekythos) with a funerary scene, attributed to the Achilles Painter, Greek, made in Athens, about 435–430 B.C. Terracotta, 17 3/4 in high x 5 5/16 in. diam. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011.14

With its narrow neck and cylindrical body, this popular type of vase was perfectly designed to hold oil. It was produced in Athens during much of the fifth century B.C. and was destined for grave use, either to be buried with the deceased or deposited at the burial by loved ones. The decoration of such jars is often appropriate to this purpose, and the Museum’s new lekythos is a typical example, showing a poignant moment of farewell between a man and a woman, perhaps husband and wife.

The decoration is attributed to the Achilles Painter. As is so often the case, we don’t know the real name of this masterful draftsman, and rely on the nickname devised by the English scholar of Greek vase-painting, Sir John Beazley (based on an amphora in the Vatican Museums that depicts the Greek hero Achilles). The Achilles Painter is widely recognized as one of the finest Athenian vase-painters of his time, capturing in his delicate lines the grace and finesse of contemporary sculpture, such as the carved figures on the Parthenon friezes, and evoking the art of ancient wall-painting that no longer survives.

At first sight, however, the painted decoration of this lekythos is not easy to discern. Several factors may account for its faint decoration: surface weathering (after all, the object is 2,500 years old), a problem during its firing, or perhaps because the figure decoration was only lightly applied to begin with. Most likely the figures’ clothing would have originally been colored.

Composite image of the lekythos under natural light showing the faint painted outlines of the two figures

In order to study, understand, and ultimately display the vase, we needed to explore imaging methods that would help make the original drawing more visible. In conservation work many different imaging techniques are used to reveal features on artifacts that are difficult to see with the naked eye. Most of these techniques are borrowed from other professions, such as x-radiography from the medical field. In this case, however, we were less concerned with seeing “inside” the vase, and more interested in getting a better view of the painted details on the surface.

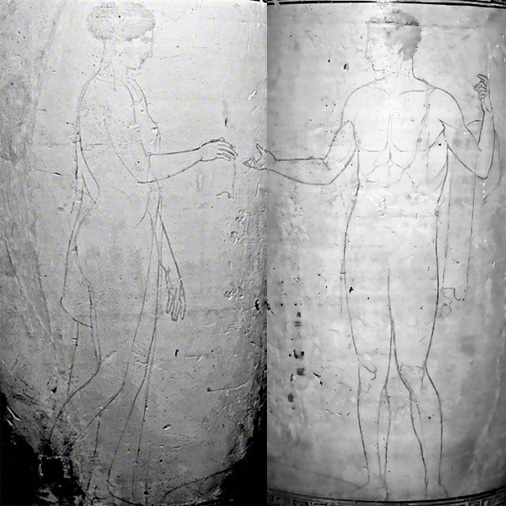

In order to do so, conservators employed a technique used by forensic scientists to acquire evidence at crime scenes: ultraviolet light (UV). Since some materials absorb ultraviolet light and re-emit it with a distinctive fluorescence or “glow,” imaging techniques using UV can provide information that would otherwise be invisible under normal lighting conditions. Conservators made use of this method with a tool known as a CrimeScope, a forensic ultraviolet light source that, through a series of filters, enabled us to examine the lekythos under various wavelengths (long and short) in the ultraviolet spectrum.

Composite image of the lekythos under UV light showing the more cearly readable outlines of the two figures

When studied with the CrimeScope, the white surface of the lekythos reflects UV light, while the dark painted lines of the figures absorb it and thus appear black. By manipulating the wavelength range, we increased the contrast to make the painted lines appear as clearly as possible.

Photographs taken under these lighting conditions now accompany the vase on display, and this forensic technique has revealed the images painted long ago in all their graceful beauty. The figures’ outstretched hands—a parting gesture—are now clearly visible, and we can also see a shield lying flat on the ground between them. Traces of a helmet resting upon the shield have also been identified. The man is a warrior preparing to depart for the battlefield. The woman bids him farewell—he may never come back.

This article is fascinating. It helps people experience the beautiful world of ancient Greece. I did a paper on a vase by the Niobid painter last year at the Getty and have been fascinated by Greek vases ever since.

This scientific method of using ultraviolet light to see hidden lines on an art piece is great, could it be possible to be applied on paper artwork like manuscript, wood, or cloth?