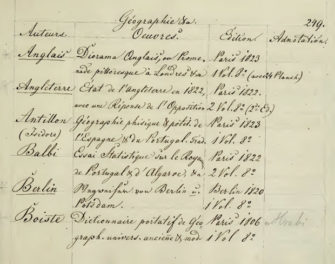

Joyce Cutler Shaw on Capitol Hill. Documents from the series We the People: Message Monument #1, 1976, Joyce Cutler-Shaw. Xerox print, 11 x 8 1/2 in. Gift of Maria Karras, BFA RBP, MA. The Getty Research Institute, 2018.M.16.17. Courtesy of and © Joyce Cutler-Shaw Estate

The exhibition MONUMENTality at the Getty Research Institute examines monuments—real, imagined, destroyed, or never-built—as markers of history and repositories of collective memory. In this post, co-curator Katherine Rochester tells the story of one never-built monument by artist Joyce Cutler-Shaw, whose plan for a sculpture composed of ice from all 50 states was planned in 1975 and only realized 28 years later. —Ed.

In 1975, San Diego-based artist and environmental activist Joyce Cutler-Shaw published WE THE PEOPLE: Proposal for an Artwork. The limited-edition brochure outlined an ambitious ice sculpture to be erected in Washington, DC, for the US Bicentennial in 1976. To be installed in the winter with the expectation that it would melt in the spring, WE THE PEOPLE: Message Monument #1 was both an admission of ecological fragility at the dawn of global awareness concerning climate change and a hopeful symbol of national unity. The project was ultimately derailed, but for Cutler-Shaw, who routinely developed complex artworks that unfolded over several years, WE THE PEOPLE: Message Monument #1 and its attendant debacle provided a roadmap for redefining brick-and-mortar monuments as ephemeral occurrences.

In a letter of endorsement for Cutler-Shaw’s project, cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead observed that WE THE PEOPLE “would leave no biodegradable waste behind it nor any controversy over changing tastes in public monuments.” This post will explore Cutler-Shaw’s commitment to shifting the parameters of public monuments from enduring, singular structures to temporary, collective assemblages whose gradual attenuation acknowledged the reality of a changing climate.

Joyce Cutler-Shaw’s finalized brochure. A Proposal for an Artwork: We the People: Message Monument #1, 1976, Joyce Cutler Shaw. Brochure, 11 x 8 1/2 x 1/16 in. Gift of Maria Karras, BFA RBP, MA. The Getty Research Institute, 2018.M.16.1. Courtesy of and © Joyce Cutler-Shaw Estate

WE THE PEOPLE: Message Monument #1, Part One, 1976: Government Gridlock as Conceptual Art

WE THE PEOPLE: Message Monument #1 was deliberately designed to trickle slowly through official government channels. Cutler-Shaw envisioned a 55-foot-long and eleven-foot-high ice sculpture made from the combined waters of the 50 states, to be collected in cooperation with each state’s respective senators. Its base would be inscribed with important dates from American history, to be determined via a Congressional poll. Its proposed location, the Capitol Grounds, required an Act of Congress to approve. And its proposed period of exhibition, the 200-year anniversary of the founding of the United States of America, necessitated its endorsement by the Committee on Arrangements for the Commemoration of the Bicentennial.

This quixotic cocktail of civic and bureaucratic protocols was the monument’s raison d’être—and also the reason why it never came into existence. Cutler-Shaw spent a month lobbying for the project on Capitol Hill. She published monthly newsletters updating supporters on the project’s progress, collected water samples, gained important endorsements, and, finally, even secured sponsorship of the necessary bill from Congressman Wayne Hays (D-Ohio), who shuffled it onward to the Joint Committee on Arrangements for the Commemoration of the Bicentennial.

In June 1976, things seemed to be going well. Cutler-Shaw received notice that Lindy Boggs, Chairman of the Joint Committee on Arrangements for the Commemoration of the Bicentennial had recommended that the House Subcommittee on Library and Memorials slate the project for immediate approval. “Thank you for directing this very meaningful and symbolic Bicentennial project to the attention of the Joint Committee,” wrote Boggs.(1) But there were counterforces at play.

Boggs indicated that the Architect of the Capitol, the Hon. George White had expressed concerns about siting the sculpture on the capitol grounds, fearing that it would set an unwelcome precedent for “an expression of freedom of speech in the form of a structure.”(2) A breaking scandal involving Congressman Wayne Hays, the bill’s original sponsor, put the legislation in additional jeopardy. Hays had been an advocate for the project since Cutler-Shaw first contacted him in March 1976.(3) However, when the Washington Post revealed that the congressman had paid staffer Elizabeth Ray $14,000 a year in public funds to enter into an extra-marital affair, the resulting FBI inquiry put many of his sponsored bills on hold. Facing severe obstacles, Cutler-Shaw returned to Washington to lobby for the bill. Despite her efforts and widespread support, the necessary Subcommittee on Library and Memorials was never convened. Congress adjourned in October without ever holding the promised hearing. WE THE PEOPLE died in the Subcommittee, a casualty of the Hays scandal.

In her December Newsletter, Cutler-Shaw outlined the transition of the artwork from probable public sculpture to conceptual artwork: “The WE THE PEOPLE monument cannot be realized as a dimensional, if temporary sculpture. The legislation for it died in the Subcommittee on Library and Memorials when the 94th Congress adjourned sine die, October 1, 1976. However, WE THE PEOPLE sculpture concept endures as paragraphs of history in the Congressional Record of February 3, 1976 as House Concurrent Resolution 542.” (4)

Cutler-Shaw assembled the documentation of her odyssey through Congress and declared the project a conceptual artwork in three parts: “The Congressional Poll,” “The Waters of the 50 States,” and “An Act of Congress: An Odyssey.” These key components would form the core of her next public project, in which her vision for a national monument evolved into a global undertaking.

Waters of the Nations/Messages from the World, 1980–82, Joyce Cutler-Shaw. Courtesy of and © Joyce Cutler-Shaw Estate

Waters of the Nations

Rather than opting for a less ambitious monument after the demise of WE THE PEOPLE: Message Monument #1, Cutler-Shaw scaled up. This time, her vision came to fruition.

Waters of the Nations/Messages from the World (1980–82) was a multi-part, durational monument commissioned by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and UNESCO to promote water conservation and sanitation. Like Message Monument #1, a central component of the monument was a massive ice sculpture, or, as Cutler-Shaw described it, “a concrete poem in ice” that “transforms from solid to liquid to vapor.”

The sculpture spelled out the word “survival” in frozen water samples from over 90 countries. Many of the samples came from holy sites, including the Meiji shrine in Japan, the Vatican in Rome, and the Ganges in India. The monument unfolded in stages. On August 6, 1982, the ice sculpture was installed at United Nations Plaza in San Francisco, where a flock of homing pigeons, organized with help from the American Pigeon Federation, began a cross-country relay to the United Nations Plaza in New York City. They arrived in October. Carrying messages from artists, scientists, and ambassadors printed on microfilm stored in World War II–era message capsules, the pigeons embodied an epic feat of coordination similar to the collective organization needed to address climate change. Indeed, the messages they carried echoed this sentiment.

One message carried by pigeon, from Dr. Jonas Salk, a medical researcher and virologist who developed one of the first successful polio vaccines, called for human ingenuity in the face of dramatic environmental and technological transformation:

“in this critical period we are on a frontier, but it is not territorial or technological, it is human and social. In this period of changing conditions and values, doubts arise as to our ability to cross this frontier and to meet the demands of the future. We will, in the process of responding to the forces and limits of nature, learn whether we have the capacity to meet this challenge. If we do, then we will emerge from the present period not merely as survivors, but as human beings in a new reality.”

As a procedural artwork that relied on the complex activation of systems—both governmental and social—Waters of the Nations/Messages from the World united nature and the city, scientists and artists, and pigeons and politicians in celebration of the UN’s “Water Decade.” According to Cutler-Shaw, the goal was “to encounter the world in the city on international territory.” As the ice began to melt, the letters began to disappear, until, by some stroke of fate, poetry, or serendipity, only the second letter of the word remained. Marveling at this chance occurrence, Cutler-Shaw mused: “Who could have predicted that the last letter standing would be u?”

Message Monument, 28 Years Later

Cutler-Shaw’s commitment to creating large-scale public artworks that raise political and social consciousness about environmental issues continued well past stand-alone projects like WE THE PEOPLE and Waters of the Nations. In 1979, she founded the Landmark Art Collaborative, a collective whose mission is to create initiatives that unite art, the environment, and architecture in the public sphere. Writing in 1976, art critic and activist Lucy Lippard observed that “Shaw visualizes her artifacts as having increasingly broader ramifications, like ripples out from a single stone thrown in the pool of the viewer’s consciousness.” The ripple effect of WE THE PEOPLE: Message Monument #1 reverberated from the project’s original inception in 1976 all the way up to 2003, when it was finally installed on the plaza of the Geisel Library at the University at the University of San Diego. The exhibition, Library Quartet, held across four libraries in the San Diego area, finally provided an arena for exploring Shaw’s lifelong engagement with language across multiple media in her home state of California.

Documentation relating to the first iteration of WE THE PEOPLE: Message Monument #1 is held at the Getty Research Institute, while her personal and professional archives are housed at the University of California San Diego Library’s Special Collections & Archives. Both are available to researchers, and our hope in highlighting WE THE PEOPLE in our MONUMENTality exhibition is that it will spur further scholarship on this pioneering, but not sufficiently known, California artist.

Photograph of Joyce Cutler Shaw Holding Model of Proposed Monument in Front of the Capitol. Documents from the series We the People: Message Monument #1, 1976, Joyce Cutler Shaw. Xerox print, 11 x 8 1/2 in. Gift of Maria Karras, BFA RBP, MA. The Getty Research Institute, 2018.M.16.2. Courtesy of and © Joyce Cutler-Shaw Estate

Notes

1. Letter dated June 15, 1976, Getty Research Institute Special Collections, 2018.M.16, Maria Karras, T5, MK 152.

2. Joyce Cutler-Shaw, Newsletter, October-November 1976, Getty Research Institute Special Collections, 2018.M.16, Maria Karras, T5, MK 152

3. Letter dated March 9, 1976, Getty Research Institute Special Collections, 2018.M.16, Maria Karras, T5, MK 152

4. Joyce Cutler-Shaw, “An Act of Congress: An Odyssey,” December 1976, Getty Research Institute Special Collections, 2018.M.16, Maria Karras, T5, MK 152

Comments on this post are now closed.