This weekend marked the start of the 2012 Olympics, a spectacle with 10,500 Olympic and 4,200 Paralympic athletes in competition across 26 sports, from handball to taekwondo to the good old-fashioned pentathlon.

The Olympics we’re familiar with today are an exaggerated revival of the ancient Greek ceremonies held to honor the god Zeus. Since the first modern games in 1896, the Olympics have grown in size and prestige. But in this flurry of national competition, intense sport, and celebration, has that much really changed since the early Olympiads?

In some ways—such as the inclusion of women athletes, the high-tech training, and the logo-laden uniforms—today’s Olympics are utterly modern. But in others, as curator David Saunders explained to me in a recent visit to the “Athletes and Competition” gallery at the Getty Villa, they’re hardly different at all.

Athletes and Competition (Gallery 211) at the Getty Villa

1. Sports Demand Money, Beauty, and Grit

Foreground: Prize Vessel from the Athenian Games, 363–362 B.C., attributed to the Painter of the Wedding Procession, vase-painter; signed by Nikodemos, potter. Terracotta, 35 1/4 in. high. The J. Paul Getty Museum. Background: Mosaic Floor with a Boxing Scene, Gallo-Roman, made in present-day Villelaure, France, about A.D. 175. Stone and glass, 81 7/8 in. square. The J. Paul Getty Museum

Sports are an expensive business, and it was no different in ancient times. Olympians were men of rank and riches: only the wealthy could afford time to train, the money to buy equipment or horses and armor for equestrian competition, and the means to travel safely and quickly to the games by mule, cart, sea, or horse-drawn chariot.

Then as now, the ideal body type was a young man of healthy, muscular, and equal proportion—an athlete. The Greek ideal nude was male, and all athletes were, of course, male as well. Many sculptures of ancient athletes show them not in action, but at rest, the better to admire their form.

Physical beauty, wealth, and time were not the only requirements for aspiring competitors. High pain tolerance and strength were needed as well. In A.D. 220, author Tony Parrottet points out, it was noted that “Eurydamas of Cyrene won the boxing, even though his opponent knocked out his teeth. To keep his opponent from having any satisfaction, he swallowed them.”

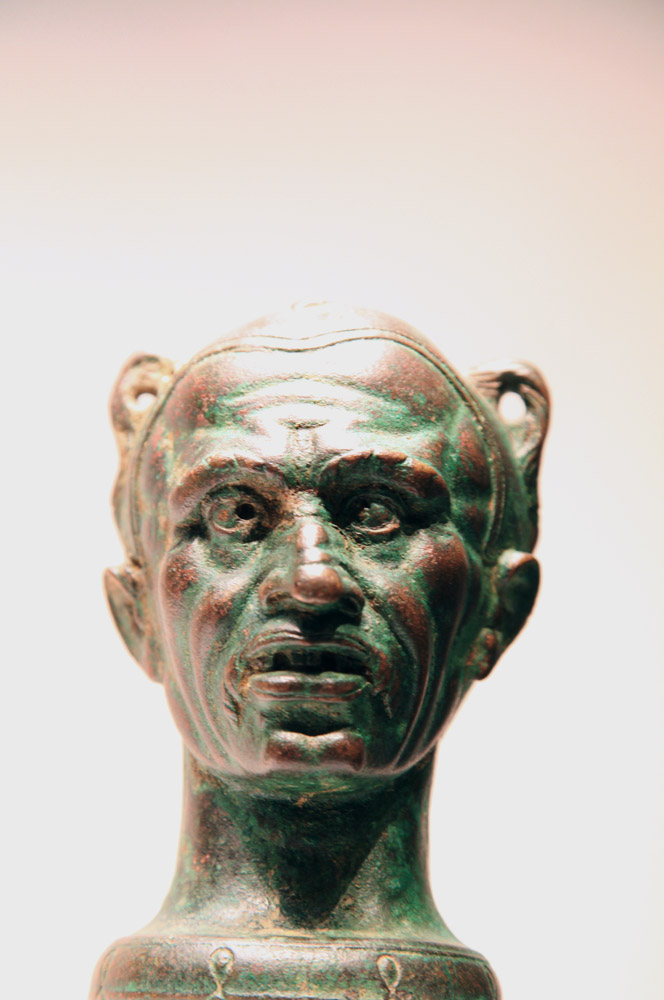

Balsamarium in the Form of a Boxer’s Head, Graeco-Roman, A.D. 2nd century. Bronze with silver, 6 3/4 in. high. The J. Paul Getty Museum

2. Sponsors Claim Their Share of Glory

Mixing Vessel with Athletic Activities and Battle Scenes (detail depicting the pankration), Greek, Athens, 510–500 B.C., attributed to the Leagros Group. Terracotta, 23 1/16 in. high. The J. Paul Getty Museum

We’ve all seen “brought to you by McDonalds” and laughed about Olympic athletes sitting around a fast food joint gorging on fries and milkshakes. But though there weren’t any corporate logos at the ancient games, the idea of sponsorship isn’t new.

Mary Beard writes about the Olympics, “Some of the most prestigious wreaths of victory went not to the athletes themselves but to men whom we would call ‘sponsors.’ The grandest event of the Games was the chariot race, but the official winner was not the man who actually did the dangerous work, standing in the chariot and controlling the horses, but the king, princeling or plutocrat who had funded him and paid for the training.”

Though competition is individual, an athlete never makes it to the Olympics by himself– he shares his glory with his city-state and the patrons who paid his way.

Gold Wreath, Greek, 300–100 B.C. Gold, 7 11/16–9/16 x 25 3/8 in. diam. The J. Paul Getty Museum

3. Athletes Carefully Cultivate Their Image

Today, young sports fanatics use posters of famous athletes to keep their dreams afloat. Parents and children alike scream their heads off at athletic events, tremble with excitement at autograph signings, and actually spend money on bobblehead versions of their favorite players.

Image was important to ancient athletes too. Wealthy ancient winners had sculptures carved celebrating their bodies and their victories, to be displayed lavishly at the arena and in their hometowns. For those who couldn’t make the journey to see the new celebrity, poets such as Pindar wrote odes to the triumphant athletes to share with the masses.

Statue of an Athlete, Roman copy after lost Greek original by Lysippos, late 1st century A.D. Marble, 54 ¾ in. high. The J. Paul Getty Museum

Beyond these factors, not much has changed since ancient times for another reason, too: the act of valiantly pushing one’s body to the brink of endurance, perfection, and even injury for team and country is still a primal embrace of survival—and of community spirit. Even if there is some hand-to-hand combat and a broken tooth or two.

Comments on this post are now closed.