Monumental funerary vases from the Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, now on display at the Getty Villa

I’ve had the privilege of studying the vessels that are displayed in Dangerous Perfection: Funerary Vases from Southern Italy for over six years now, and to be honest, I still find them rather overwhelming.

For one thing, they’re large, mostly a meter or so in height. Coupled with this is the richness and elaboration of their decoration: they’re a riot of both figures and ornament, and the eye scarcely gets any rest in looking at them. Thirdly, there’s their complex but fascinating modern history. Discovered in fragments and purchased by a Bohemian diplomat, they were pieced together by one of Naples’ leading vase restorers, acquired by the Prussian king for his museum in Berlin, stored in bunkers during World War II, taken to the Soviet Union at the end of the war, returned, and then treated and conserved at the Antikensammlung (Collection of Classical Antiquities) in Berlin and at the Getty Villa.

It does require an effort to study these complex objects, but perseverance is worthwhile, for they can help us to understand how an ancient people in Southern Italy found ways of thinking about something we still don’t understand today: death and what lies beyond.

The vases were all made in Apulia (a region of southern Italy) in the mid-fourth century B.C., and were used by the local native people. Sadly, we have very little written evidence for what they thought about mortality, but the vases that they deposited in their burials offer a fruitful source of information.

The Here and Now (Or the There and Then)

Documented excavations leave no doubt that vases like those in the exhibition were buried in graves. Their scale and quantity offers a reasonably reliable indicator of their owners’ wealth and status. Indeed, just to transport a hulking krater from pottery workshop to graveside would have demanded a considerable effort.

Also noteworthy is that twelve of the thirteen vases in the exhibition have holes in the bottom.

Detail of the inside of a funerary krater during conservation. Look beyond the staples, fabric, and clay that were used to piece the vase together in the 19th century, and you can see the ancient hole at the base. (Interior detail of a funerary vessel, about 350 B.C., associated with the Iliupersis Painter. Made in Ceglie del Campo, Italy. Terracotta, 43 5/16 in. high. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin) Photo: Marie Svoboda

This isn’t unusual for funerary vessels, and indicates that they were not used as containers for food, oil, or drink, as many ancient vessels were. Instead, they were literally showpieces—made to be seen, studied, and admired during burial rites. And that helps to explain the choice of painted images that adorn them.

The most explicitly funerary images on these vases are scenes that show a grave monument. These vary in size and shape, but they don’t look too different from today’s gravestones.

Funerary Vessel with Figures Approaching a Gravestone (detail), 350–325 B.C. Connected with the work of the Darius Painter and possibly the Perrone Painter. Made in Ceglie del Campo, Italy. Terracotta, 35 13/16 in. high. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung. Photo: Johannes Laurentius

The monuments are attended by an entourage of young men and women who bring various offerings: boxes and vessels, adornments such as ribbons, florals, and wreaths, and ladder-like items that look like xylophones. All of this suggests that the graves were tended by those left behind, but the exact meaning of these scenes has nevertheless vexed scholars. (More on them below.)

Myths as Metaphors

Seen en masse, the vases in the exhibition offer a remarkable compendium of Greek myth and legend. In most cases, these are tales that already had a long history even when the vases were produced in the mid-fourth century B.C. But they acquire a specific meaning when they appear on vessels destined for the grave. Although the themes vary, we can spot some recurrent threads.

Death Is Getting Carried Away

When Zeus took Europa, he turned himself into a bull, which transported her across the sea.

Funerary Vessel with Eros; Europa on the Bull (center, top register); and Lapiths Battling Centaurs, 350–325 B.C. Connected with the work of the Darius Painter and possibly the Perrone Painter. Made in Ceglie del Campo, Italy. Terracotta, 38 9/16 in. high. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung. Photo: Johannes Laurentius

When Phrixos was rescued from likely death, his mother did so by sending a ram that could fly.

Funerary Vessel with Phrixos on the Ram, 340–310 B.C., attributed to the Phrixos Group Painter. Made in Ceglie del Campo, Italy. Terracotta, 18 1/2 in. diam. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung. Photo: Johannes Laurentius

Both mortals were lifted from the terrestrial world and taken somewhere else. It’s not too much of a stretch to think of this as a metaphor for death: leaving behind one’s home and family, transported somewhere that is perilous to reach (note that travel over the sea is itself a recurrent motif), but under the guidance of a benevolent divinity.

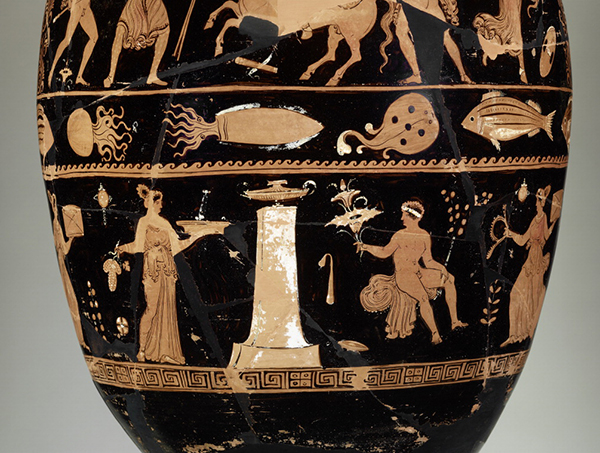

With this in mind, let’s look at the various scenes on the neck and body of one of the volute (spiral-handled) kraters.

Funerary Vessel with Herakles Slaying Geryon; the Calydonian Boar Hunt; and Nereids (side A); and with Medea, Jason, and the Argonauts; Bellerophon Slaying the Chimaera; and Nereids (side B), 340–310 B.C., attributed to the Phrixos Group Painter. Made in Ceglie del Campo, Italy. Terracotta, 46 7/8 in. high. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung. Photo: Johannes Laurentius

They’re impressive as depictions of mythical battle and adventure, but acquire a new tenor when we think of travelling long distances. When Herakles fought Geryon (seen on the neck of side A of this vase), he did so in the far far west. When Bellerophon sought the Chimaera (seen on side B), Pegasus, yet another flying animal, transported him eastwards. And perhaps the most famous adventurer of them all—Jason with his Argonauts—is depicted on the neck of side B. His quest for the Golden Fleece was intended to be the death of him, but he triumphed over the odds. A mourner who understood these stories might take solace from that.

Death Is Fighting Monsters

Whilst we’re looking at this krater, we can spot a second thread: Herakles slaying the triple-bodied Geryon; Bellerophon conquering the part-goat, part-snake, part-lion monstrosity that is the Chimaera; Meleager and his comrades overcoming the frenzied Calydonian Boar. All of these achievements involve the dispatching of fearful and terrifying creatures. Is it too much of a stretch to see this as another comforting metaphor for those face-to-face with the frightening prospect of death? If those heroes were able to overcome their worst nightmares, well, just perhaps…

Death Is Becoming a God

Funerary Vessel with the Marriage of Herakles and Hebe, 375–350 B.C., Associated with the Group of the Moscow Pelike. Made in Ceglie del Campo, Italy. Terracotta, 43 11/16 in. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Looking up to a hero is what we might call a “coping strategy.” On another of the kraters, we see Herakles’ marriage to Hebe. It’s a happy and festive scene, perhaps out of place on a funerary vessel. But if you know your Greek myth, you’ll be aware that Herakles didn’t really die. He was made immortal and joined the gods on Mount Olympus. And as if the point weren’t clear enough, Hebe, his bride, is the goddess of youth. Death need not be the final curtain.

Death Is Happily Ever After

Which leads me to the final theme, and the most problematic. What’s unavoidable in surveying the vases in the exhibition is the recurrent presence of Dionysos and his entourage of dancing and cavorting satyrs and maenads.

Funerary Vessel with a Horned Male Head; a Dionysian Scene; and Greeks Battling Amazons (side A); and with Female Figures; a Dionysian Scene; and Greeks Battling Amazons (side B), 350–325 B.C. Made in Ceglie del Campo, Italy. Terracotta, 40 9/16 in. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

We’re perhaps most accustomed to think of Dionysos & co. in association with wine, drinking, and good times. But there’s something more afoot here. As mentioned before, we have very little in the way of written evidence as to South Italian eschatologies (beliefs about the afterlife). But there are tantalizing hints in the form of obscure texts written on thin slivers of gold that have been found in graves in Southern Italy and Northern Greece. These so-called Orphic tablets contain obscure references to—amongst other things—an ever-flowing spring, a white cypress, and the Lake of Memory.

Scholars have assembled the fragmentary evidence to argue for the existence of certain “mystery rites,” initiation into which would provide secure passage into a blessed afterlife. As we might expect, Hades and Persephone are sometimes named in the texts, but Dionysos is occasionally referred to as well, suggesting that he may be part of these rituals. This would make sense, as Dionysos’ well-established association with intoxication is part of a much broader web of associations that centered around the god’s connection with changing states. And there’s no greater change of states than from life to death.

Exactly how this maps onto to the scenes of Dionysos on the Apulian vases remains a subject of ongoing examination. To date, none of the gold tables have been found in Apulia, but their discovery in nearby regions have led some to study the depictions of figures at grave-monuments with this mystery cult in mind.

Funerary Vessel with a Female Head; the Judgment of Paris; and Figures at a Gravestone (side A), and with a Female Head; Youths and Women; and Figures Approaching a Gravestone (side B), 350–325 B.C., connected with the work of the Darius Painter. Made in Ceglie del Campo, Italy. Terracotta, 36 1/4 in. high. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung. Photo: Johannes Laurentius

The figures are consistently youthful and show no sign of lamentation or grief. This has given rise to the hypothesis that they’re not so much a realistic depiction of mourners of the deceased here on earth, but an aspirational vision of the hereafter, where all enjoy eternal youth and a paradisaical existence.

Whether this vision of the afterlife came true for the ancient Apulians, we will never know. But for clues about what they hoped and feared, these vases provide valuable glimpses.

_______

David Saunders discusses the ancient hereafter at Death Salon Getty Villa on April 26. Tickets are sold out, but we invite you to follow the day’s events on Twitter at #DeathSalonGV. Audio of all talks will be posted after the event.

Did I miss it, or did you explain why the vessels have holes in the bottoms?

In truth, it’s still not really clear to me. In other contexts, we might think that it could facilitate the pouring of libations, but that doesn’t seem to be the case for Apulian vases. Possibly it might have assisted with their display.

Do we know how the kraters were placed by the mourners? Many ancient Roman graves had openings over the face of tge corpse, so that relatives could pour offerings of milk into the mouths of their departed ones. Were the kraters perhaps positioned so that the holes may have served a similar purpose? A wealthy or powerful or well-loved person might be expected to receive enough drink-offerings that without a large vessel to hold them as they trickled down, the offerings might overflow.

Thanks for your question, Valerie. For these vases from Ceglie, we don’t know exactly how they were deposited, as they were recovered in fragments. But other similar vases have been found within graves – or sometimes in contexts that indicate that they served as grave markers. Images on the vases themselves sometimes suggest the latter too. As so often with archaeological material, there’s no single rule of thumb and we should be open to variety at a regional or even local/communal level.

For a little more information, I’d recommend Didier Fontannaz’s essay in T.H. Carpenter et al (eds.) The Italic People of Ancient Apulia, which has some useful discussion and references regarding the use of vessels at the site of Taranto. Incidentally, this volume is a great resource in general, presenting the latest research (in English) on South Italian vases.