Self-Portrait, 1975, Robert Mapplethorpe. Gelatin silver print. Promised Gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

While facilitating tours of the Getty Center exhibition Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium (March 15–July 31, 2016; curated by Paul Martineau, associate curator of photographs at the Getty Museum), I encounter a large range of responses. Some viewers respond kinetically in the galleries, moving towards the photographs and mirroring the poses of the models. Several have responded to snippets of the labels aloud: “Oh, they were lovers!” Others have comments and questions that they share in side conversations or with the group: “How long did he have AIDS?” “What type of cameras did he use?” “Did Mapplethorpe make his subjects look a certain way?”

As an educator who has been leading tours in the galleries at the Getty Center for nearly 10 years, I’ve learned that validating our visitors’ views can mean hearing disparate, even contradictory, ideas. I view discourse about art as necessary in part because we share a limited number of universally held values today. I always seek to promote an exchange of ideas, welcome emotions, promote inquiry, and create a safe space for supporting meaningful dialogue about art.

I’ve observed that many visitor responses to the Mapplethorpe exhibition focus on the tension between the erotic content of the work and the exquisite quality of the prints and their display. Here I discuss a couple of the questions that visitors have raised on my tours, which give a small sense of the myriad tastes, sensitivities, and interests that visitors bring to Mapplethorpe’s work and that offer me endless possibilities to engage them in conversations about interpretation.

From Questions on Technique to Representation

Recently a high school photography class from Fresno, California visited Robert Mapplethorpe. One student in particular responded to the exhibition by saying, “I want to learn how to light photographs like Mapplethorpe did.”

Flower Arrangement, 1986, Robert Mapplethorpe. Gelatin silver print. Promised Gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

As we discussed her ambition, I explained that replicating Mapplethorpe’s use of light—whether soft or hard, thrown or reflected, diffused, concentrated, contained, or raking—is no small technical goal. And it prompts consideration of what effects such light have on viewers’ interpretations of photographs.

One might describe Mapplethorpe’s studio as a theater in which he staged imitations, exaggerations, idealizations, aggrandizements, and magnifications of his subjects. In a 1988 interview, Mapplethorpe said, “My whole point is to transcend the subject . . . go beyond the subject somehow, so that the composition, the lighting, all around, reaches a certain point of perfection.” To create these effects, he used a number of techniques to perfect the form of his subjects—natural or artificial lighting; flat or structured backgrounds; tight cropping; iconic centrality; distracting detail kept to a minimum. Each facet of the photograph—whether the subject, the pose, the lighting, or the print—bring meaning to the work: even the slippery sheen of the gelatin prints serves to polish his subjects.

Mapplethorpe’s use of light is often seen as creating an idealized aesthetic, which, in turn, can make his photographs seem cool and distant. The light traces interesting paths across the skin of his models and gives them the look of sculpture, but are these people only illuminated at the surface level? Does this light allow the humanity of Mapplethorpe’s models to emerge? Or does it limit the viewer’s ability to empathize with them? Indeed, some art historians have suggested that the disciplined formality of Mapplethorpe’s practice presents subjects like specimens rather than muses.

From Questions of Representation to Display

During a different tour I was asked, “Don’t you think these images contribute to seeing the black male body as hypersexualized?”

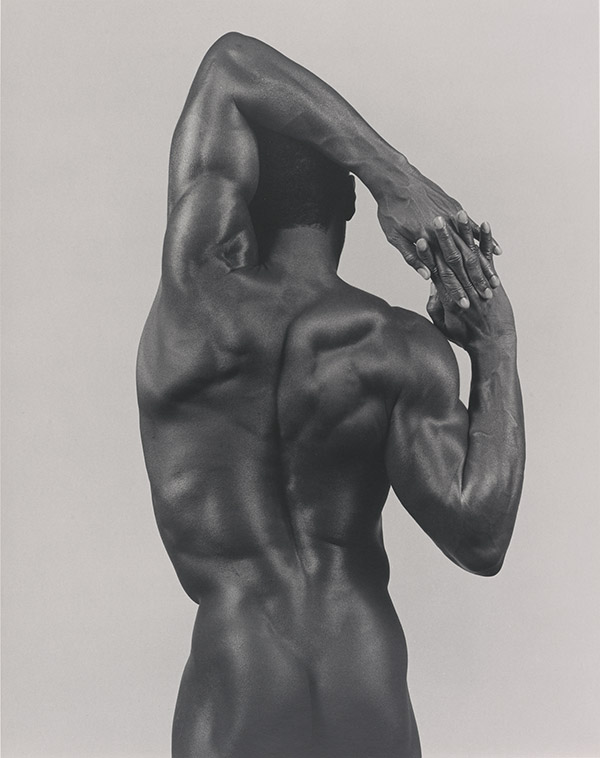

Derrick Cross, negative 1983; print 1991, Robert Mapplethorpe. Gelatin silver print. Promised Gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

There is a sexuality and erotic charge present in Mapplethorpe’s photography, and several critics and art historians have raised pointed questions about fetishism in his work. I chose to engage this visitor’s response with examples from scholarship that highlight the multitude of possible ways to read the relationship between photographer, model, and audience.

Victim, vulnerable, exposed, exploited: all are ways to describe certain human subjects in Mapplethorpe’s work. Another view is that the photographs depict the agency of and relationship between two consenting adults: the photographer and his model. Is it possible to imagine that there may be pleasure for those under Mapplethorpe’s lens? The subjects expand beyond the norms of traditional nude figure studies: some seem to exaggerate stereotypes, others break them. They transgress gender, embody desire, and echo classical ideals. For instance, the photograph, Derrick Cross, is reminiscent with Michelangelo’s Slaves. Has Mapplethorpe appropriated the Renaissance artist’s classical motif that since ancient times has suggested bondage? What questions does the juxtaposition of beauty with bondage or liberation raise for viewers?

Another way to engage questions about sexuality, eroticism, and fetishism in Mapplethorpe’s work is to look at the way the photographs are displayed in the galleries. Throughout the exhibition photographs are placed in thoughtful “conversation” meant to prompt visitors to respond. Some are arranged like fine art prints, framed and arranged carefully on the walls. Other materials are displayed in vitrines, including archival materials and the X Portfolio, the latter alongside strong discretionary signage. The height of the X Portfolio vitrine puts physical distance between the photographs and small children, but it also encases the portfolio as a single unit, encouraging an intimate experience. How does placing these photographs in a vitrine mediate our sense of what is public from what is private? Does this presentation make it easier or more difficult to engage with issues of sexuality? Does the physical action of looking down into a vitrine render the photographs socially “safe” when compared with others—such as Man in a Polyester Suit—that are framed and hung on the wall?

From Taboo to Art

Mapplethorpe did much to expand the photographic medium’s potential, redefining the boundaries of what is taboo for art to approach. His art is permeated by tension, as are reactions to it. Like Mapplethorpe’s American Flag (1977), a strong image whose meaning has been much debated, yet still draws people together, points of contention in exhibitions can also draw people together. I view tours in this way: Engaging with diverse viewpoints enables individuals to join a conversation and perhaps unite in a sense of collective spirit.

______

Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium is on view at the Getty Center from March 15 until July 31, 2016, then will travel to Sydney and Montreal. William Zaluski and colleagues offer daily exhibition tours at 2:30 each afternoon through July 31, 2016.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.