Joe, N.Y.C., 1978, Robert Mapplethorpe. From The X Portfolio. Selenium toned gelatin silver print mounted on black board, 7 11/16 × 7 11/16 in. Jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; partial gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the David Geffen Foundation, 2011.9.41.6. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

On the Friday in 1990 when the collection of 175 photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe, called The Perfect Moment, previewed at the Contemporary Arts Center (CAC) in Cincinnati, 8,000 people showed up to see them.

The CAC was seven blocks from my law office. On the Saturday morning that the exhibit opened to the public, we heard that the Hamilton County prosecutor had empaneled a grand jury to get an indictment by noon, so we sent out scouts to determine when the police were going to arrest the CAC’s director, Dennis Barrie. But Cincinnati is a small town, and our scouts told us that the cops had stopped for lunch along the way.

Eventually, Dennis was charged with obscenity for five photographs of explicit gay S&M sex and one count of exhibiting two photographs of nude children. If convicted, he could have spent two years in jail and paid $2,000 in fines. The CAC would have had to pay $10,000 in fines. The psychic cost for countless artists and museums as they self-censored to avoid obscenity charges also would have been high.

I spent the next six months working on Dennis’s defense. A jury judged him not guilty that October. The trial demonstrated that the rights to freedom of expression designated in the Constitution must be fought for—and that they sometimes hinge on narrow legal distinctions.

I had been working on First Amendment cases since the 1970s. That was a decade of changes in attitudes toward art with sexual content. The Kinsey Report’s findings had been accepted by the culture by then, and magazines and filmmaking reflected the sexual revolution. Then, in the 1980s, VHS and Betamax players produced an explosion of pornographic films people could watch in the privacy of their homes instead of theaters. By the late 1980s, sexual content was a bigger part of our culture and our lives.

The controversy over Mapplethorpe’s work is often attributed to his explicit homosexual subject matter. But I wondered if the trouble in Cincinnati wasn’t more about race. There were photographs of black men and white women, after all. And our city is on the edge of the South (Kentucky is just across the river) and 46 percent African American. We had integrated during the ‘70s, but were backsliding into segregated neighborhoods by the ‘90s, with whites moving into small cities and villages in the suburbs.

To me, it was mind-boggling that prosecutors would go after the CAC, a vital and legitimate institution that had been hosting exhibitions since the 1940s. Before trial, we were optimistic that the case would be dismissed, despite the climate of hysteria around Mapplethorpe, because it should have been clear that an organization like the CAC would never do something without a serious artistic purpose. After all, the exhibit was a retrospective of years of work, and it had shown elsewhere in the country. A museum would be a protected institution from these charges; however, the judge said the CAC was not a museum but a gallery because it had no permanent collection. We were boggled by this.

So we had to go to a jury trial. Again, we were optimistic. I was familiar with Miller vs. California, a 1973 case that said that obscenity had to be proven by three so-called prongs. First prong: Would contemporary community standards say that the work as a whole had only prurient interest? Second prong: Did the work show sexual acts in a patently offensive manner? Third prong: Did the work, taken as a whole, lack serious artistic value? I had worked on cases for pornographic movies like The Devil and Mrs. Jones talking about the first and third prong—the movie had a plot and it might be patently offensive, but it was not morbidly preoccupied with sex.

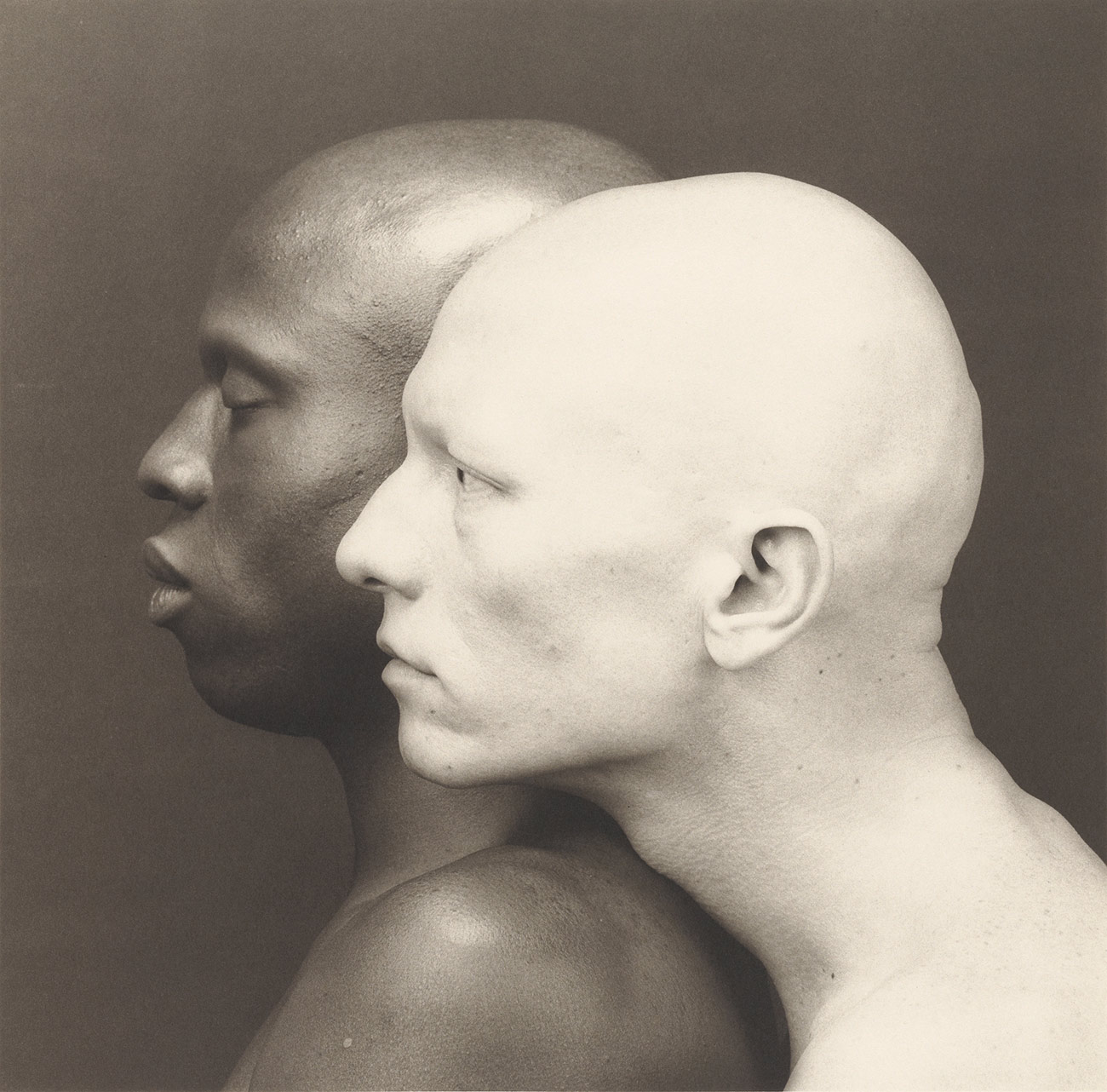

Ken Moody and Robert Sherman, 1984, Robert Mapplethorpe. Platinum print, 19 7/16 × 19 3/4 in. Jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, with funds provided by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the David Geffen Foundation, 2011.7.23. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

A big challenge was to make sure the jury understood the context of the photographs. It was equally important that I would comfortably talk about sexual practices with a more clinical vocabulary, so the jury understood them in a legal context. But we were handicapped because the jury couldn’t see the actual exhibit photographs; only the photos and video taken by the police of the exhibit were shown. (The exhibit had gone to Boston by the time of the trial.) So we got all of our expert witnesses to see it at the CAC so they could describe exactly what they saw, and explain the context and the presentation of the photographs as art.

In discussing whether the photographs had artistic merit, we geared the defense to the idea that art didn’t have to be pretty. It can be challenging. I can see Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and leave depressed. But that’s not a problem with the performance—the artistic value doesn’t get determined by what you feel afterwards. For example, the importance for the world of images of the Holocaust is huge. We don’t like those images, but they are vital to telling the story.

That was a winning argument. The jury deliberated for two hours and acquitted Dennis Berrie and the CAC.

The trial created an important history of a jury validating this approach to art. It sent a message that artists and museums can tell us things that we often don’t or can’t talk about easily. The way times and norms change was part of the exhibition. You could see how Mapplethorpe evolved from seeking attention and photographing himself toward the more interior still lifes and portraits. Art really reflects the period of time it’s made in. We don’t come to grips with what happened in that time until 20 to 30 years later. It’s good to see that Mapplethorpe’s work today is being recognized as the artistic accomplishment—and advancement—that it really is.

In retrospect, we made another smart decision: The prosecutor had offered to drop charges on the five photographs if Dennis would plead guilty to two misdemeanors of showing nude children. We said no. Looking back, the repercussions of taking a plea deal for disseminating photos of a minor in a state of nudity could have been a death blow for the CAC—and disastrous for Dennis. Now with all the consciousness over those labeled sexual offenders, such a crime would be a felony and could land him on a sexual offender registry.

For me, winning the case—in a trial that we made about art—was a great moment. The Mapplethorpe exhibition divided the city, and the art world there split against itself. Everybody was afraid. The CAC withdrew from the local arts association so they wouldn’t tarnish the symphony. By winning the case on grounds that this was art, that it was important for humanity, the CAC’s reputation was bolstered. In the years since then it’s raised money for a beautiful new building and a collection.

But that case (and others from that time) also scared museums and artists who don’t have the resources to fight. There’s a lot of self-censorship by museums, which are especially leery of showing work with children. The repercussions of offering work that could be labeled “dirty” remain serious. Museums’ ability to show what they think is important is still somewhat dependent upon who is running the Justice Department.

Artists who are considered to be on the edge are still targets. I recently defended a young photographer who was doing a series on birth and death. He got permission to take photos at the morgue, but foolishly sent them out for developing. He was reported to the police and prosecuted for abuse of a corpse. At the end of the trial the prosecutor kicked the box of photographs and told the jury, “Mr. Sirkin’s defense of art is bullshit. Art is only what we’d take home and hang on the wall.”

The artist spent 12 months in prison.

_______

See Mapplethorpe’s photographs in Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium at the Getty Museum and LACMA through July 31.

Text of this post © Zócalo Public Square. All rights reserved.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.