Splitting my time between the Getty Center and Getty Villa as the 2016-17 graduate intern in Education (School Programs), I often spend my Wednesday and Thursday afternoons teaching gallery docent workshops for both new and continuing volunteer educators. Together, we explore best practices for facilitating inclusive learning opportunities, which are rooted in the belief that collaborative meaning-making takes place through conversation. There are many different ways to lead compelling, challenging conversations with students, but my personal favorite is through the art of collaborative storytelling.

Stories have long been used in art museums as an effective strategy for engaging students in shared dialogues about objects and big ideas. Stories are particularly successful when they activate listeners’ imaginations, and this can be achieved through both fictional and nonfictional narratives. As an ideal medium to connect artworks with students’ personal experiences, stories encourage active participation, critical thinking, creative thought, and expression of emotions. Narratives also naturally tap into language skills, supporting students’ linguistic fluency and vocabulary development. On an even more fundamental level, stories help students retain information: stories stick with us, more so than theories or dates or definitions.

In early January, I co-facilitated a teaching workshop for gallery docents with David Crabb, host and educator at The Moth, a nonprofit that celebrates oral storytelling. Aptly titled “The Art of Storytelling,” this three-hour session examined how to develop, refine, and implement collaborative storytelling during school tours. We experimented in the Getty Villa’s galleries, workshopping different ways we might approach storytelling with antiquities. In this workshop we rejected the factual narratives—such as who made this particular object, its materials and construction, and how it came to be in the Museum—and focused instead on the stories embedded in the art that might be unlocked through close looking, questioning, speculation, and discussion.

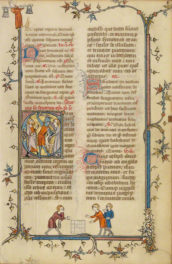

Poet as Orpheus with Two Sirens, 350–300 B.C., Greek, made in Tarentum, South Italy. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 76.AD.11. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Storytelling—and storytellers—do not neatly fit into a single mold. There are no hard and fast rules dictating what makes for an accomplished presenter and which narratives are the most valuable to share. But, in my role as an art museum educator, I have learned three key ingredients for making student-directed stories stick.

1. Plan backwards.

When I begin to craft a tale with Getty student visitors in mind, I always start with the punchline. Thinking through the arc of my story helps me to figure out the beats that will keep the students hooked. But if I’ve done my research correctly, I might never arrive at the punchline I’ve created. Instead, through active engagement and dialog, our story might twist and turn through the students’ own experiences and interpretations. Together, we decide what topics to explore, producing personal and shared meanings that shift and bend as new voices chime in. I watch for opportunities to respond to the students’ comments with narratives and ideas that help them make meaning of those observations. It is up to me to construct a dynamic bridge between the students and the object, developing a collaborative narrative with enough humor, details, and dialog to keep the audience engaged.

2. Make—and keep—a promise.

The kinds of stories that stick with listeners—both in the moment and years down the road—make a promise and, importantly, keep that promise. As a storyteller, I promise students that objects can speak directly to them, even if they appear irrelevant at first glance. Sometimes I only need a simple opener, such as “There’s a mystery for us to solve here; what is the object trying to tell us?” or “If you lived 2,300 years ago, what would you …?” By establishing a social contract between myself and my audience, I invite listeners to truly engage with the artwork in a way that feels welcoming and accessible to them.

3. Share the load.

Telling stories naturally demands a great deal of effort, foresight, and knowledge from the speaker. But, that doesn’t mean you need to do all of the work; the most successful stories require listeners to work with you. I invite students to speculate about an artwork’s mysteries by asking them to actively respond to questions that are suggested by the object. For example, when teaching with the sculpture in the photograph above, I engaged gallery docents with the following questions: What might the man have been thinking as these two half-female, half-bird figures surrounded him? What sound do you think his now-missing instrument might have made? Such open-ended questions operate like magnets, immediately drawing participants into the discussion and shared meaning-making (and story-making!) process. My role during this stage is to encourage student input, connecting the dots between what they are seeing and saying with information that supports their exploration.

As one docent remarked, “storytelling is a natural fit for teaching with artworks. Every piece has stories; you just have to look for them.” Indeed, stories are powerful tools. They can cross the barriers of time—connecting past and present—and invite students to experience the similarities between ourselves and others, real or imagined. They pull you in, encouraging you to share personal experiences and connect with artworks through imaginative play. Because of their presentation and content, sticky stories stay with us, acquiring personal and shared meaning significant to all who take the time to stop, listen, and share.

I’d love to hear from you! How do you tell stories that encourage critical thinking and closer looking at the Getty? How do you make your stories stick?

Comments on this post are now closed.