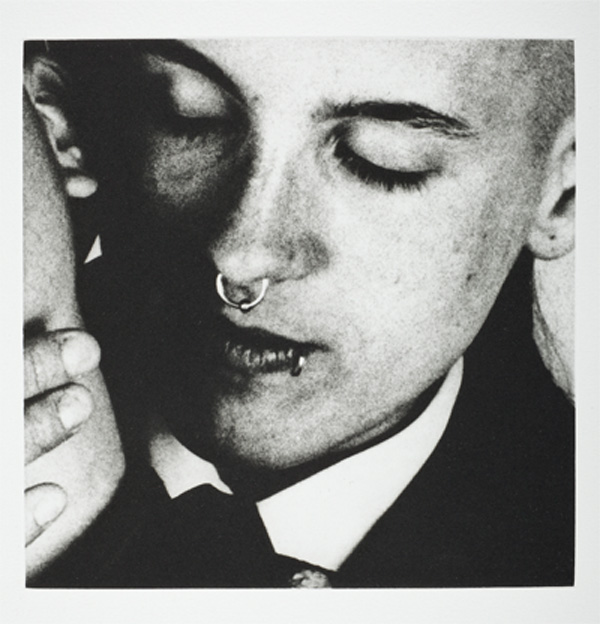

Self-Portrait, ca. 1970, Robert Mapplethorpe. Gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Drawn largely from the Mapplethorpe archive jointly acquired by the two institutions in 2011, Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium will present the full scope of the artist’s work, from his earliest collage-based works, through his early Polaroids, to late floral still-lifes and portraits. With such rich visual and archival resources on display, we will have an unprecedented opportunity to reflect on Mapplethorpe’s legacy, which has been both social and aesthetic.

Robert Mapplethorpe was born in Queens in 1946 and grew up in a middle-class, Catholic household. In 1967, he enrolled at the Pratt Institute, where he majored in advertising, and then switched to graphic design, which allowed him to focus more on drawing and painting. At first he conformed to masculine norms and was a member of ROTC and the National Honor Society of Pershing Rifles, but, like many young people of his generation, he gravitated toward the counterculture, attracted by a glimpse of alternative lifestyles.

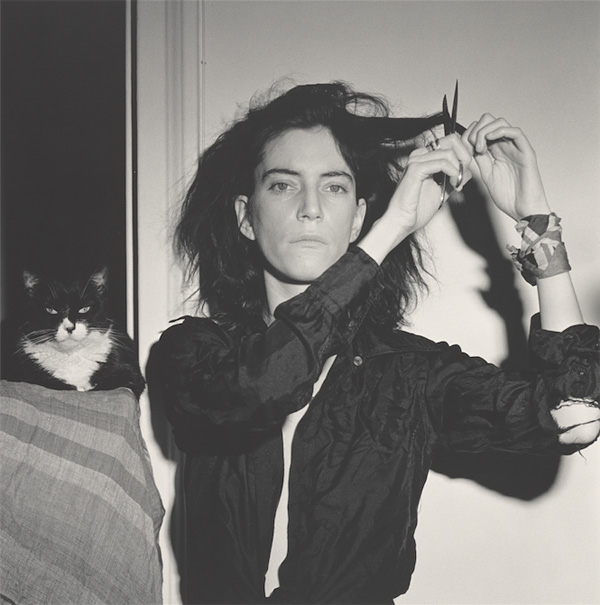

Not yet a photographer himself, he appropriated photographic imagery from publications and advertisements, manipulating them, spray-painting over them, and incorporating them in collages. Already he was revealing both his iconoclastic tendencies and his pragmatic determination to make art despite having little money to spend on supplies. Patti Smith—his close friend from this period, whom he met in 1967—immediately recognized Mapplethorpe’s talent and ambition. When Mapplethorpe took up the camera (a borrowed Polaroid) in 1970, he realized that photography was the perfect medium for him and, as he put it, for the moment.

The observational potential and instantaneity of the Polaroid triggered Mapplethorpe’s full creative powers. He enjoyed the way the camera could be a means of possession, seduction, play, and control. But ultimately Mapplethorpe was after a more refined, upscale product than the Polaroid could generate. He wanted to make art, and this meant using high-end equipment, establishing a professional studio, controlling print quality and quantity, showing in respected galleries and museums, and making money.

Assisting him in reaching this level was Samuel J. Wagstaff, Jr., a well-known curator and collector, and Mapplethorpe’s lover and mentor. (A concurrent exhibition at the Getty, The Thrill of the Chase: The Wagstaff Collection of Photographs, presents selections from Wagstaff’s private collection.) Thanks to supporters like Wagstaff and to his own charisma and drive, Mapplethorpe became adept at moving between uptown and downtown circles, both socially and artistically. In only around fifteen years, he built an impressive body of work and exhibition history, starting with his first solo show in 1973 and concluding in 1989 with major retrospectives and his death at age 42.

In keeping with his careful career formation, Mapplethorpe defined his body of work as he produced it, sequentially numbering the prints he approved for editioning. (The final body of work, represented in the archive held by LACMA and the Getty Museum, totals 1,969 images. Mapplethorpe’s edition sizes ranged from 3 to 60 prints.) For some artists, a retrospective exhibition can spur this process of self-evaluation, and Mapplethorpe had two such exhibitions in 1988–89, a survey at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the traveling exhibition The Perfect Moment organized by the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia. By that time, awareness of his mortality—he had been diagnosed with AIDS in 1986—was also clearly a factor. Before he died, Mapplethorpe wanted to establish once and for all the continuity of vision uniting all his photographs—portraits, sex pictures, and flowers. This was both a personal credo and, he must have felt, a successful and original “brand” that constituted his artistic legacy.

Poppy, 1988, Robert Mapplethorpe. Jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

In addition to refining his body of work, Mapplethorpe established a foundation in May 1988 naming his attorney Michael Stout as the executor of his estate and the president of the foundation after his death, and determining the mission it upholds to this day: supporting AIDS research and photography publications and exhibitions at the institutional level. Mapplethorpe’s attempts to shape his legacy were, however, overshadowed by the explosion of the Culture Wars at the exact moment of his death. The first assessments of Mapplethorpe’s achievements occurred not at the behest of critics or historians, but on the Senate floor and in a Cincinnati courthouse. The vilification of Mapplethorpe’s work by Senator Jesse Helms led to the cancellation of The Perfect Moment at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., to the arrest of Contemporary Arts Center director Dennis Barrie on charges of pandering obscenity in Cincinnati, and to a persistent association of Mapplethorpe with provocation, controversy, and pornography.

Two Men Dancing, 1984, Robert Mapplethorpe. Promised gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Ultimately, the jury acquitted Barrie. (LACMA curator Robert Sobieszek and former Getty Museum director John Walsh were among the art world professionals who defended Mapplethorpe on the witness stand.) While the controversy fueled record attendance at the Contemporary Arts Center, it left the institution in a budget crisis, unable to pursue a proposed new building campaign. The case was considered a victory for freedom of expression, but it had a limiting effect on the public and critical understanding of Mapplethorpe’s work. The Helms Amendment debates and the Cincinnati trial cast Mapplethorpe as a provocateur and a protagonist in the Culture Wars and the AIDS crisis as both played out in the early 1990s. It was momentarily unclear whether he would go down in history as a political and sexual radical or as a successful and genuinely talented artist.

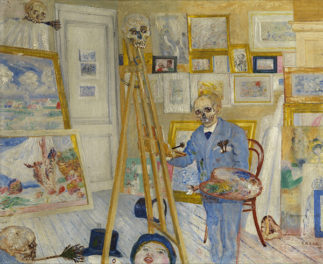

While academic dialogue stalled, some of Mapplethorpe’s fellow artists presented subtle and interesting reflections on his work. One example, Catherine Opie’s O Portfolio of 1999, is on view at LACMA concurrently with the Mapplethorpe retrospective in the Photography Foyer gallery through September 16, 2016. Opie still recalls her first encounters with Mapplethorpe’s X Portfolio (1978) in galleries in San Francisco while she was an art student. Today she lives with a Mapplethorpe print in her home, and the Mapplethorpe Foundation supported her 2008 retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum. In the O Portfolio, Opie displays her identification with Mapplethorpe, even as she stakes out a territory he never explored, lesbian leather S&M culture. She also took up a variant medium, photogravure, which Mapplethorpe explored only sporadically. The seven photogravures are details of pictures taken over the course of a year during casual studio shoots with friends—emulating Mapplethorpe’s insistence that the photographer is a participant as well as an observer.

Untitled, 1999, Catherine Opie. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Ralph M. Parsons Fund. © Catherine Opie

Looking at Mapplethorpe’s work as a catalyst for personal affinities and desires, Opie took a uniquely artistic approach, augmenting the established positions taken by curators and publishers. Meanwhile, as the 90s drew to a close, Mapplethorpe (the blue-chip artist) was quite visible in the art market and in museums. Carefully curated exhibitions, most of them presented in Europe, reinforced his craftsmanship and singular vision. At the turn of the twenty-first century, this version of Mapplethorpe seemed to be solidifying into history.

Yet there was more to learn about him and his work, as revealed in Patti Smith’s National Book Award-winning memoir Just Kids (2010). In this book, Smith shared her loving admiration of Mapplethorpe, introducing him as a young man in search of himself and fueled by desire, far from prior conceptions of him as a canny careerist, censorship target, or AIDS activist. Whereas art-critical literature tended to situate him in the institutional and sociopolitical structures of the 1980s, Smith placed Mapplethorpe in relationship to the avant-garde orbit of the late 60s and early 70s. As several reviewers pointed out, Just Kids was a book that could be enjoyed across generations on the basis of its tender story and lyrical writing. It was not Smith’s intention to reassess Mapplethorpe as a photographer—although she does assert her total conviction of his artistic integrity—but she did contextualize his practice in a different way than art historians had up to this point. By going into detail about his early obsessive drawing, his proclivity to scavenge and improvise collages and constructions, and his intention to make and market jewelry, she establishes him as inherently an artist before he considered taking up the camera.

Patti Smith, 1978, Robert Mapplethorpe. Jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Twenty-five years after Mapplethorpe’s death, the controversies that raged around The Perfect Moment have receded into history, although we must remain vigilant in our protection of freedom of expression. Today Mapplethorpe has many emulators in popular culture, fashion, and the art world. At least one feature film, a television series, and a documentary are in the works. All of this creates an eager audience for the exhibitions that will open in Los Angeles and later travel to Montreal, Sydney, and another international venue. Of course, our 2016 version of Mapplethorpe will be no more definitive than Mapplethorpe’s own version, or Jesse Helms’s, or Patti Smith’s. It is always important to realize that at any given moment, we see the artist we want to see.

Text of this post © Museum Associates/LACMA. All rights reserved.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.