Celebrations of great military victories in ancient Rome could be an ostentatious affair: triumphing generals entered the city in pomp, followed by prisoners of war, the precious objects from the booty heaped on wagons, and painted tableaux showing key stages of the military campaigns; this procession was often followed by feasting and public spectacles. But it may come as a surprise that in this display of might, plants had a role to play.

Pliny the Elder, the first-century CE author of the encyclopedic work The Natural History, certainly had his own views on this and, expressing at once surprise and reproach, wrote:

“It is a remarkable fact that ever since the time of Pompey the Great even trees have figured among the captives in our triumphal processions…” —Natural History 12.111, trans. H. Rackham

Indeed, when the general and statesman Pompey the Great celebrated his magnificent triumph in 61 BCE for his many victories in the East, he displayed in his triumphal procession also live plants: the balsam and the ebony tree. Why?

Pompey’s triumphal celebration, in terms of populations subjugated and geographic areas covered, was an unprecedented affair that made his deeds comparable to those of Alexander the Great. Considering the geographic coverage of Pompey’s military activity and the number of populations involved—and hence the number of prisoners, precious metal objects, weapons, illustrations of battles fought, and so forth—he really did not need to parade trees. But these were not just any trees. These plants were clearly associated with specific geographic areas that had been subdued: the balsam (or balsam of Mecca) with Judea and the ebony tree with Ethiopia. Pompey’s triumph was the moment when, for the first time in Rome’s history, plants were taken as a clear symbol of the land from which they came, and this is the role they played in his triumph.

These two plants also had notable commercial value: the resin from the balsam tree was highly sought after in the manufacture of perfumes and medical treatments, and ebony was greatly appreciated for the quality of its wood. Indeed, the plantations of the balsam plant were later so central to the revenues the Roman state could extract from Judea that during the first Jewish revolt (66–70 CE) the Jews had tried to destroy them; later, the Romans placed the cultivations under direct control of the treasury. Pompey was not the first Roman general to come back from overseas bringing trees with him. The best-known case, just over a decade earlier than Pompey’s display, is that of Lucius Licinius Lucullus and the cherry tree, which he imported into Italy from Pontus.

The East Garden at the Getty Villa, inspired by ancient models. Lush plantings, water features, and sculpture were features of the luxurious ancient Roman garden.

At the time of Lucullus and Pompey, gardens had acquired an important role in Roman private architecture and were fast acquiring a central role in public architecture, too. Under the influence of Hellenistic architecture, during the second century BCE Roman urban houses and country villas had acquired increasingly larger ornamental gardens. Framed by a peristyle, as one can see in the famous House of the Faun in Pompeii or in the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum, the central garden space became a place to display to visitors and friends the refined tastes and culture of the owner: the plants and sculptures chosen for the garden could all convey specific symbolic meanings and allude to the owner’s learning. So, for instance, planting plane trees in the garden was not only a practical choice, since they offered plenty of shade during the hot Mediterranean summers. The plane tree had also been the plant associated with Plato’s Academy in Athens. In the writings of Cicero, we find that a garden with plane trees was understood as a symbol of the Academy, thus signifying that the intellectual pursuits that were conducted in its shade were worthy of Plato’s school.

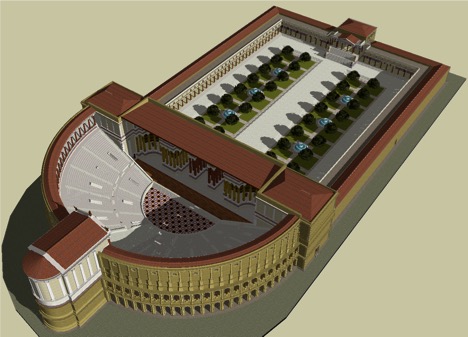

The theater and great portico of Pompey, from Virtual Rome. © Matthew Nicholls, University of Reading 2017

It is no surprise, then, that the next big endeavor Pompey undertook after his triumph of 61 BCE was to build a novel architectural complex featuring the first stone theater of Rome and large garden-portico. This great portico enclosure was to be a public park in which plants, statuary, and paintings on display had a highly symbolic meaning, epitomizing his great military deeds and remaining as a memento of them for the population of Rome for years to come.

New plants—and new varieties of known fruits—continued to be imported from one region of the Roman world to the other during the imperial period. Whether as symbol of newly conquered lands and of the revenues flowing into the state’s coffers or as novelties to be enjoyed at the table, new plants, fruit varieties, and gardens attracted remarkable interest on the part of prominent Romans.

_______

Hear Annalisa Marzano speak about Roman gardens at the Getty Villa on March 18. Reserve your free tickets here.

But the Romans weren’t the first to use ‘captured trees’ as symbols of their territorial conquests and to enhance royal gardens at home. They had picked the idea up from the East: it was practised in Assyrians from Tiglath Pileser on and in Egypt.

Indeed! In my forthcoming talk I do mention the earlier eastern examples of “botanical imperialism”. But as far as we know, in Rome’s case it was only in the 1st c. BCE that we see this phenomenon.