Subscribe to Art + Ideas:

“The reason why African Americans began these places of leisure and relaxation in the outdoors was because they were excluded from going to the white establishments.”

Around the turn of the 20th century, African Americans seeking to escape racism in the South began moving to Southern California in larger numbers. Like others who migrated to the Golden State at the time, they also came in search of new opportunities and seaside recreation. But discrimination prevailed, even out West, and Black Americans found themselves barred from accessing public pools, parks, and beaches. As a result, Black entrepreneurs and community builders created their own gathering spots, such as Bruce’s Beach in Manhattan Beach and Ocean Park in Santa Monica, where people of color could enjoy surf and sand.

These successful leisure sites weren’t embraced by everyone—it wasn’t long before white residents, local developers, and members of the KKK launched campaigns of harassment. In 1922, African Americans were forced to give up plans for a beachfront project in Santa Monica. A few years later, the oceanfront property owned by the Bruce family was seized by the city through eminent domain and the resort was shut down. Today, many of these stories of Black resourcefulness and self-determination—thwarted by racist policies—have been forgotten, if not intentionally obscured. But there have been some attempts to make amends, including California’s Governor Gavin Newsom recently signing into law a new bill that will return the oceanfront property taken from the Bruce family almost a century ago to their descendants.

In this episode, historian Alison Rose Jefferson discusses these stories as documented in her book, Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era, and the need for a more inclusive look at America’s past.

More to explore:

Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era buy the book

Transcript

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

ALISON ROSE JEFFERSON: The reason why African Americans began these places of leisure and relaxation in the outdoors was because they were excluded from going to the white establishments.

JAMES CUNO: In this episode, I speak with historian Alison Rose Jefferson about her new book Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era.

In the 1920s, African Americans were barred from many white establishments and public beaches in Southern California. So they created their own gathering spots, including Bruce’s Beach—one of the first west coast resorts for Black people. But racism reigned and in 1924, the Manhattan Beach city council used eminent domain to seize the oceanfront land from the Bruces. Now, nearly a century later, California has agreed to return this valuable property to the descendants of the Bruce family. While this story has received much attention of late, there are many lesser-known stories of how Black Americans pioneered leisure sites in the Golden State and contributed to the rapid growth of a flourishing industry.

Alison Rose Jefferson is a Scholar in Residence with the Getty Conservation Institute and the author of Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era. I recently spoke with her about her book and these oft-forgotten stories of Black life in early 20th century California.

Thanks so much for speaking with me on this podcast, Alison.

ALISON ROSE JEFFERSON: Thank you so much for inviting me.

CUNO: You write in your book that several sites throughout the U.S. catered to an African American clientele curing the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including the Poconos in Pennsylvania, Sag Harbor in New York, Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard, Amelia Island Florida, and the Gulf Resort, outside Biloxi Mississippi. How and when did this phenomenon of Black leisure sites get started?

JEFFERSON: So all of these Black leisure sites around the nation started when you began to have an African American middleclass after Reconstruction, in the latter decades of the Nineteenth century. Most of them, though, started in the twentieth century, not far from urban centers where you had large populations of African Americans. The ones that you mentioned in the East Coast began because African Americans wanted to experience the outdoors and the resort life that was becoming popular, just as white folks did.

But unfortunately, at that time, due to discrimination, they weren’t allowed, in many cases, to go and enjoy these places, ’cause Sag Harbor had a general population resort culture; the Poconos had a population that had various resorts. There was a big Jewish resort there, and the Poconos became popular in the twentieth century. Amelia Island started in Florida, as a resort in the early twentieth century. Martha’s Vineyard had been a place where the Methodists started a resort and revival camps in the nineteenth century, and African Americans started going to those revival camps and they wouldn’t let them stay in the camps.

So they set up their own places outside of the Methodist camps. And the same with some other places. Gulfside Resort was also a Methodist resort that was in the Mississippi area, near Biloxi. It lasted, actually, into more recent times. Unfortunately, the area was destroyed with hurricanes in the last ten years. It had had a senior housing population that was living there.

CUNO: Was there a particular culture that defined African American leisure sites and distinguished one region from another—say Oak Bluffs from Biloxi, Mississippi? Like particular food or dress or music?

JEFFERSON: I’m sure. They were regionally different from the standpoint of where they were located, so African American folks in the South were different than African American folks in the North. So I’m sure there was some kind of difference, in terms of the activities. In New England, you might be going crabbing; in Mississippi, that might not be what you’re doing.

You might be going sailing up in Massachusetts, but you might not be doing that doing in Mississippi. And certainly, in Mississippi, there was much more discrimination down there. So folks probably would have been more concerned about staying within the confines of the Gulfside Resort area. Whereas in Massachusetts, up on Martha’s Vineyard, they might have been residing in one area near the campgrounds, the Methodist campgrounds, but they were going all over the island.

And there was also a Native American community that was there, and there was a historically free Black community, that lived on the island of Martha’s Vineyard. So I think yes, each place had its own particulars. That’s why people went. I mean, most people that were in New York or in Massachusetts weren’t going to Gulfport; they were going to Sag Harbor or going to Martha’s Vineyard, just as the folks that go to Gulfport, they’re from the cities around that region, in Louisiana and Mississippi and Alabama.

CUNO: How did the particular phenomenon get extended to California?

JEFFERSON: The things that were attracting everyone else to California, in terms of the climate, the beautiful surroundings, new life opportunities, real estate development opportunities, all of those things were things that African Americans wanted. People sometimes forget that there was discrimination all over the United States. The reason why African Americans began these places of leisure and relaxation in the outdoors was because they were excluded from going to the white establishments.

The same kinds of things happened here in Southern California. California had Civil Rights laws from the 1890s, that said that they could go anywhere they wanted to, in terms of public accommodations. Now, sometimes those laws were laxly enforced. And then there were informal practices that also impacted African Americans’ abilities to exercise their rights as citizens. And so with that, they formed these resort areas here to enjoy the opportunities that California had to offer.

CUNO: Were they scattered throughout Northern and Southern California, or principally in Southern California?

JEFFERSON: The nineteenth century was the time of the Black migration to Northern California because that was where most people were living, in terms of California, from the time of the Gold Rush through the 1890s. And then in the twentieth century, Southern California, Los Angeles, became the center of the African American population in the state of California, and also in the West. And so with the larger population, more affluent population here, you had these sites that developed in Southern California.

CUNO: Now I gather that the war years—that is Second World War—were important growth years for Black L.A. Where did Black Californians tend to live, in which parts of greater Los Angeles, in what relationship to their employment and to the leisure sites?

JEFFERSON: So the African American population in the region did jump in the World War II years. And the earlier community allowed for that jump to happen, in terms of the numbers. And so in the 1950s, African Americans settled in the neighborhoods around Central Avenue, south of Downtown Los Angeles. Originally it was south of Little Tokyo in Los Angeles, and then it became south of what is the 10 freeway today. And what is remembered as the historic core of the African American community emerged in the early part of the twentieth century below Washington, all the way down to Slauson, and then also in the neighborhood around USC, between Exhibition and Adams, around to Western. And then there was also a small community around the Temple area in Los Angeles. And there was also a community in Boyle Heights and in Watts. And there was also a small community in Venice, California.

So with that, the majority of African Americans lived in the Central Avenue corridor. And then as discrimination and the racially-restrictive covenants were declared unenforceable with Shelley versus Kraemer in ’48 and other Supreme Court cases in the 1950s, Black folks began to move out of the Central Avenue core and move west, into the West Adams area. And then eventually, by the 1960s, into Leimert Park and Baldwin Hills, and even over to areas around La Brea and Pico.

CUNO: Tell us about the Negro Motorist Green Book. What was that and what role did it play in development of Black leisure sites?

JEFFERSON: So the Negro Motorist Green Book was one of several guides that were developed over the course of the twentieth century to help African Americans navigate traveling, so that they could find places to stay, places to eat, places to get their hair done, all these kinds of things, where they would be treated with dignity, rather than discrimination, from the standpoint of there’re some places that might have served you, but if it was a restaurant, they might’ve made you do takeout; they wouldn’t let you go into the restaurant. So the guides, like the Green Book, offered names of establishments that people could go to all over the country, and even in some Caribbean nations. And as it relates to the leisure sites in Southern California, some of the ones that were here at Lake Elsinore in Santa Monica and at Val Verde were listed in the Green Book and other guides.

CUNO: How long did the Green Books last?

JEFFERSON: They lasted from 1934 until about 1965. It was started by a gentleman who worked in the post office. And he was able to get some financing for the guide from Standard Oil. And he used the networks of postal employees to gain information about the various sites around the country that would service African Americans. And he also got information via word of mouth from folks, as well. Victor Green was the gentleman who founded the guide.

CUNO: Now, what about the early history of Bruce’s Beach in Manhattan Beach? Who were the Bruces?

JEFFERSON: So Willa and Charles Bruce were some of the early entrepreneurs in the region developing a leisure business for African Americans. Around the time that they were developing their business there in Manhattan Beach, there was also the Lake Elsinore establishments that were developed. And then in Santa Monica, African Americans were attempting to develop resort businesses there, and also in Playa del Rey.

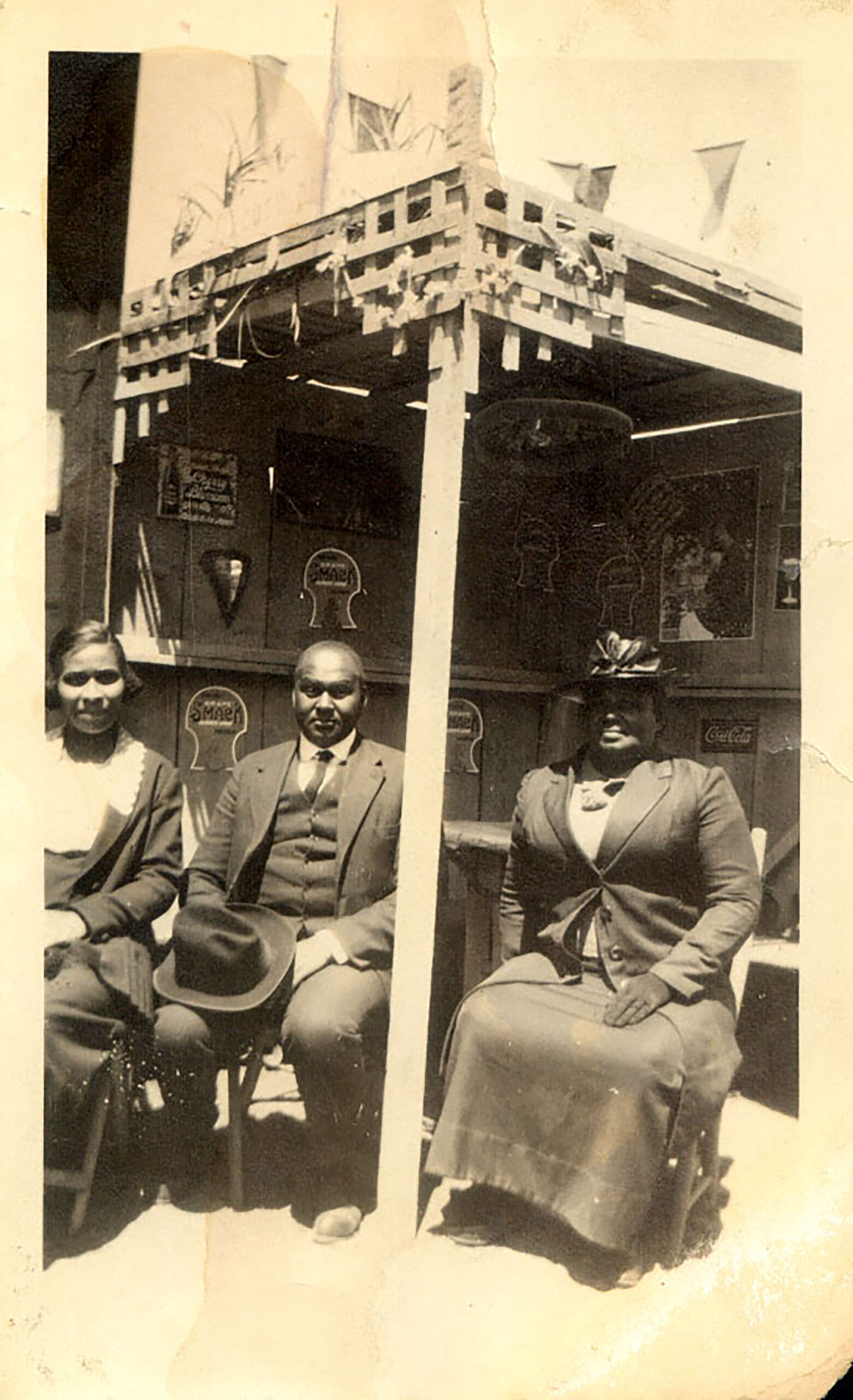

The Bruces, in 1912, Willa and her husband Charles, got this beachfront property in Manhattan Beach, and opened up a small establishment servicing African Americans who would have been coming, for the most part, from Los Angeles, down to Manhattan Beach to enjoy themselves at the shoreline. And initially, it was a pop-up tent affair, where they had places for you to change your clothes, ’cause we have to remember, a lot of people forget this, but in 1912, the freeway system was not in place.

And there were not paved roads from Los Angeles Central Avenue district, which is about fifteen miles away. Also, people forget that the cars were open air and that the car, in 1912, was a new conveyance. So there would’ve been people also still using horse and buggy to come down to Manhattan Beach. And by 1912, the electric streetcar had just been expanded to cover that area, so that made it accessible for Black folks and others from Los Angeles to get down to Manhattan Beach.

If you took the streetcar, it would’ve taken you about an hour. If you were driving, it might’ve taken you longer because it would depend on, you know, where you’re coming from and what roads you were going on. And so with this, this town was just developing. And the Bruces, just like some of the other folks that were there developing businesses and buying property, were looking at their own enjoyment at that particular moment in time; but they were also looking at how is the City of Los Angeles, the region, how is it going to be developing, in terms of population, movement, and expansion?

And so they opened this resort. And then even from the first day, they had problems with some of the white folks not wanting them there. And one of the white landowners, who was the developer of the area, George Peck, roped off the beach to keep the Black folks from being to access the water because he owned the property from the waterline up to where the Bruces’ property was.

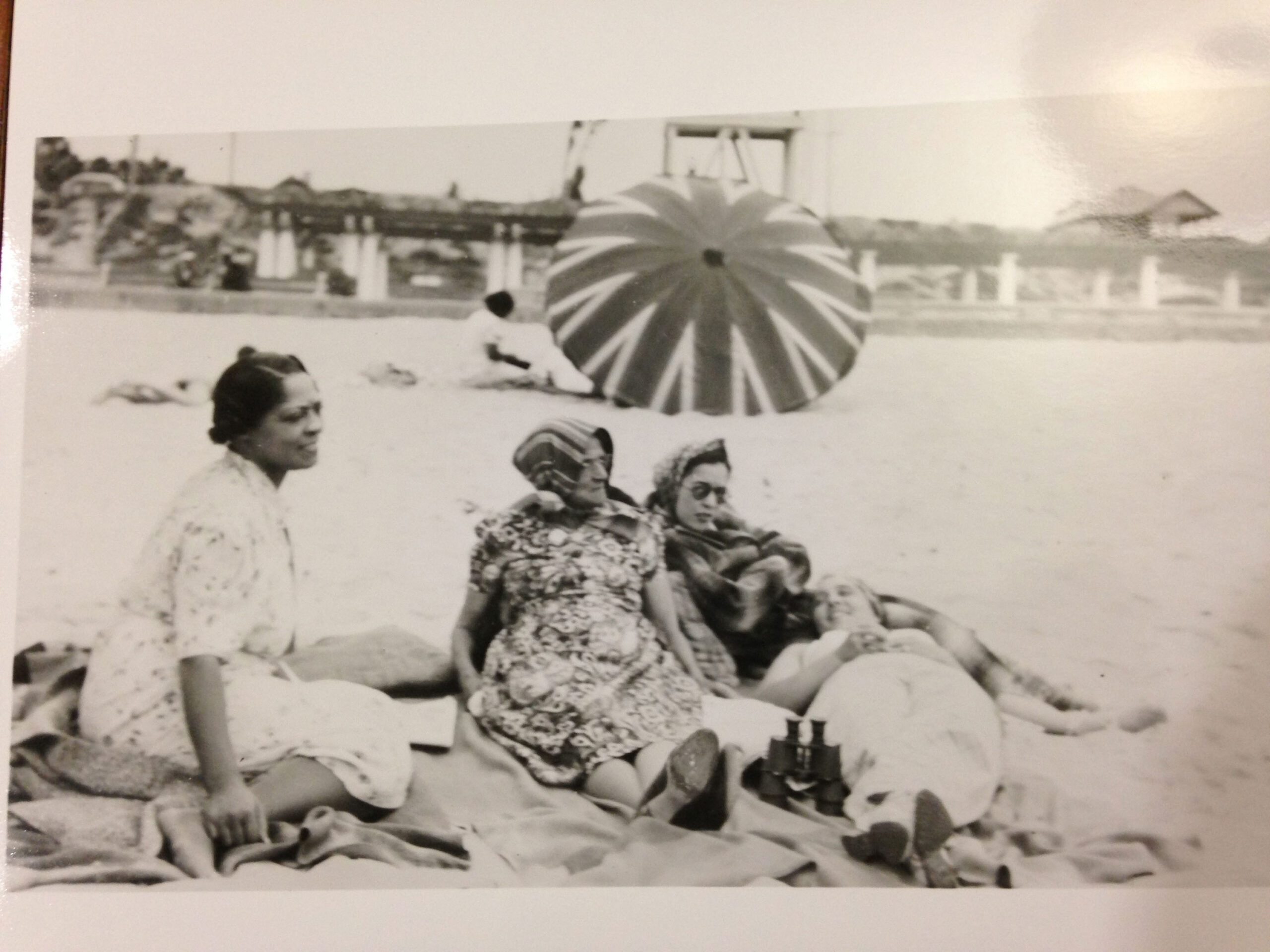

The patrons ignored that and they just walked around his area that he had roped off. Eventually, the resort continued even with these inconveniences. And there was a newspaper article in 1912, which articulated that, the white folks didn’t like the fact that the Black people had opened this resort and that they were gonna try and push them out. But the Bruces were able to hang on. They were able to build some structures there, and we have some photographs of one of the structures that they built, which eventually included a restaurant and a few rooms for changing your clothes, to get into your beach attire. And then some spaces for a few folks to stay overnight down there.

It was a very successful and popular place, until it was forcibly closed in the 1920s by eminent domain proceedings from the City of Manhattan Beach because they decided that they didn’t want the Black folks there. There were different waves of harassment that occurred with the Ku Klux Klan doing telephone campaigns to intimidate the Bruces. The city changed laws, in terms of parking, with signs up saying you could only park ten minutes. African American folks got their tires slashed. They put in vagrancy laws that said you couldn’t change clothes in your cars. They changed laws in terms of what could be developed along the beachfront, and you had to get permission from the city to do any expansion—all kinds of things, just to minimize the African American business development that was there that the Bruces had started. But the 1920s harassment action was the one that was able to close the place down, with the eminent domain proceedings.

CUNO: Now, what was the role of the NAACP in all of this?

JEFFERSON: They didn’t have a role in what formally went on, in terms of the Bruces and the other African American families that had settled around the resort area, who had vacation homes. Their role was more in making sure that it was recognized that the public beachfront was open to everyone. Because even after the Bruce’s establishment was closed and the other families were pushed out through the eminent domain proceedings, African Americans were still going down there to use the beach because there were still some other families that were there in the area. They weren’t in the area that was taken through eminent domain, from 26th to 27th and from Highland to the beach, but they were just outside of that area. So you still had a friendly place, more or less, to go because you knew people.

And so with that, the white folks were trying to keep African Americans from using the beach, so the city did a lease with one of their cronies to rope off the area between 25th and 27th Street, to say that it was a private beach. And the African Americans active with the NAACP challenged that, and they went down there and they wound up getting arrested.

There had been some other cases where African Americans were using the beach there, and they got arrested also. And so that was why the NAACP pushed the issue. And with that, their civic protest was the first civil disobedience operation of African Americans in Southern California. They were able to, through court maneuvers, establish that the Civil Rights laws of the 1890s and into the 1920s said that the beach was open to everyone.

And then shortly thereafter, the City of Manhattan Beach made a purchase of all the oceanfront land and declared that, they were doing this because they didn’t want to have any issues, in terms of the general population using the beach. So the NAACP’s protest confirmed for all citizens of California that the beach was a public space. And that’s something that we’re still fighting about today in some areas of the state, where some property owners—mostly rich property owners—are trying to keep people from using the beach in front of their homes.

CUNO: Were the Black Americans in Santa Monica living under the same circumstances as those in Manhattan Beach? Was it as difficult in Santa Monica as in Manhattan Beach?

JEFFERSON: There were challenging circumstances because discrimination was everywhere. But in Manhattan Beach, you didn’t have an African American community. You don’t have an African American community in Manhattan Beach because in 1924, with the eminent domain proceedings, they chased Black people out of Manhattan Beach.

You can see that throughline to today. There’s less than half a percent of the City of Manhattan Beach which is African American. The town has 35,000 people. That’s less than 200 people in Manhattan Beach that are African American. In Santa Monica, you have an African American community that was established in the 1880s. We have records of folks who were living there with the founding of the town, who had businesses, who owned their own homes, who were involved in working for different establishments.

And you had the first African American church established in Santa Monica in 1906. They get their first building in 1908. And so it’s a different milieu, in terms of African Americans being able to reside there in Santa Monica. Now, they also had some issues, in terms of being sabotaged by white supremacists, discrimination, and subterfuge measures when they were trying to develop resorts based on the beach. But the community in Santa Monica has persisted. Today, about 5% of the population in Santa Monica is African American.

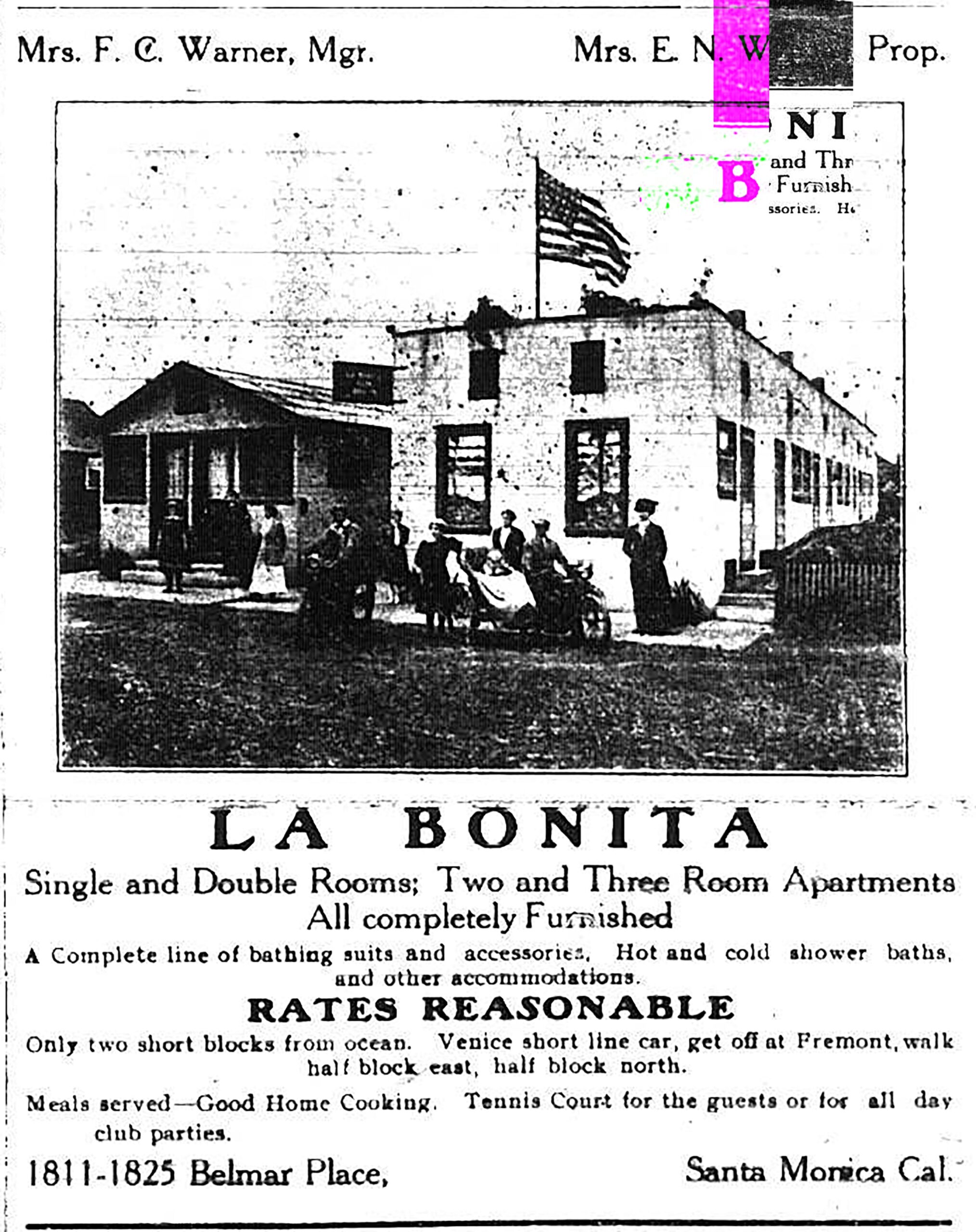

And the beach service business that did last in various iterations— La Bonita lasted through the 1950s. But some of the other efforts that African Americans tried to develop beachfront resort areas were foiled by various abuses of public power and informal discrimination.

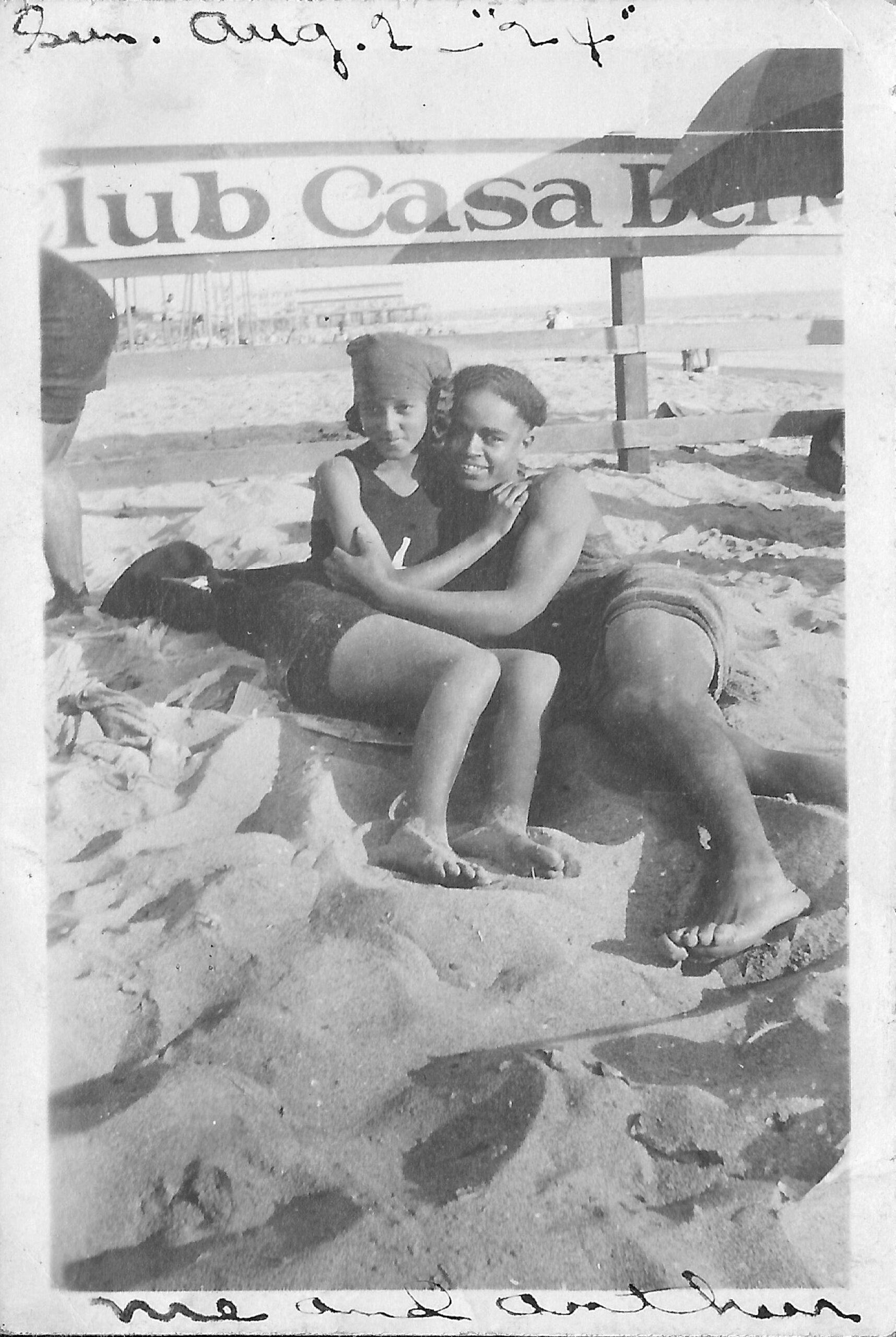

CUNO: What was the Casa del Mar Hotel like at this time, and what role did it play in all of this?

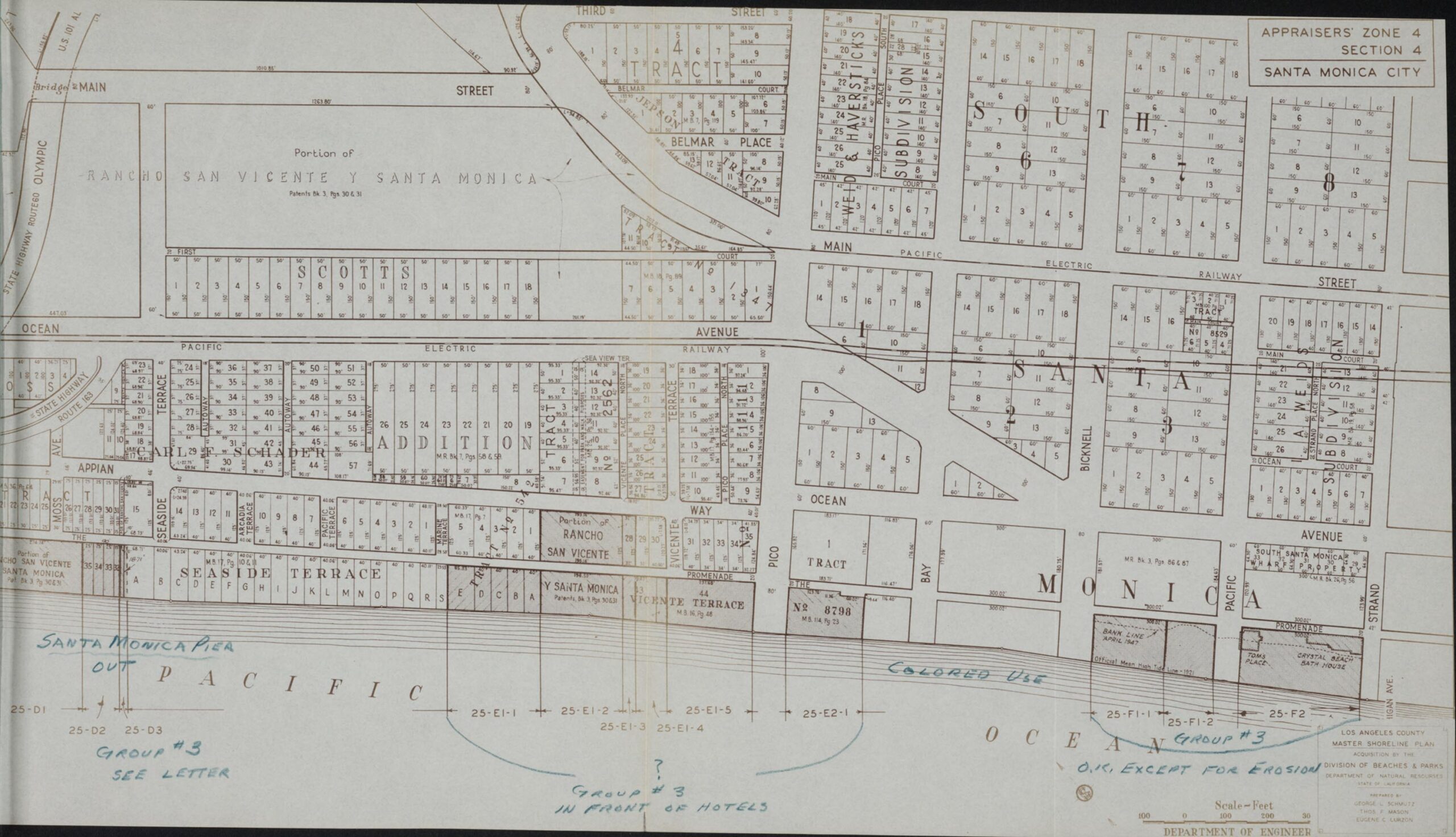

JEFFERSON: So African Americans, developed a small beach service business, La Bonita, and it was a few blocks inland from the beach. But in 1922, African Americans tried to develop a beach resort business and amusement facility at Oceanfront and Pico, right around where Shutters on the Beach is today. They were led by Norman O. Houston, who was the founder of the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance, which was one of the largest African American businesses in the country up until it closed.

And then Charles Darden, a land-use lawyer and Civil Rights lawyer, they tried to develop this space, and the neighborhood— the white protective League—they called themselves the Neighborhood Protective League, but it was a bunch of white folks who decided they didn’t want the Black people to have this space on the beach. They rallied the businesspeople and they rallied the neighborhood there in South Santa Monica, to say that they didn’t want the Black people to have this resort.

500 white folks showed up to a city council meeting and they got the city council to say that, well, if they wanna own the land, that’s fine; if they wanna build a house, that’s fine; but they can’t build a resort business. So once the land was no longer in Black hands, and some other white folks had some ideas about developing beachfront clubs and resorts, they went to the city council to ask for a change in the variance, so that they could build a resort. And so that’s what happened. The Casa del Mar got that change in variance and they started building in ’24. They opened in ’25. And then before 1930, right across the street from them, the Edgewater Club, which would’ve been the site of the African American development, they were allowed to build that space.

And then down the way, north, The Breakers club, which is now today an apartment building, was allowed to come in. So it was white supremacy and economic sabotage that pushed the African Americans out of that space there at the beach, and the white beach clubs—the Casa del Mar and the Edgewater, which is now the Shutters Hotel—were allowed to be built.

But that area from Pico down south to about Bicknell, is where African Americans had been hanging out at the beach because the historic African American community that formed early in the South Santa Monica Beach area was up the street, around where the church was at 4th and Bay Street. And that was Phillips Chapel Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, which was the first African American led and owned institution in Santa Monica. And it still exists today.

And then folks were also moving into the area where the Civic Auditorium is now. And that area had a street called Belmar, and that was where the La Bonita establishment was. And then there was also another neighborhood that was just north of Santa Monica High School, where Nick Gabaldón, who is the first documented surfer of African American descent, and his family lived, alongside some other African American and Mexican American families.

CUNO: We’ve been talking about the historic leisure sites that you write about in your book, called Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites During the Jim Crow Era. Tell us about your recent projects, especially the Commemorative Justice Initiative in Belmar Park.

JEFFERSON: So we have a project at the historic Belmar Park, which is at 4th and Pico in Santa Monica. It’s a sports field, and it’s on the old parking lot of the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. And that project, I hope, is something that will inspire folks to learn more about their history, and also inspire them to think about what their dreams are, as it relates to their lives.

What we have there is an installation that commemorates, that recognizes people, places, and events of the historic African American community that was in the South Santa Monica Beach neighborhoods before the removal of the community that was there where the park is, that included African Americans before 1950, and the folks who got taken out with the freeway and expansion of the school and the Civic Center.

And so there’s fifteen panels that are around the park that talk about various folks that were living in the area, and were involved in Black businesses, were involved in civic life, in terms of education, in terms of organization development, and then folks that just were living in the neighborhood. And there’s a piece of public sculpture that was done by artist April Banks, which is on the 4th Street side of the park, near the entrance of the sports field.

And so we hope that people will walk around the park and look at the panels and see information about the people, places, and events, and there’s also an essay. There’s also lesson plans that were developed with UCLA’s Teacher Enrichment program, for third, fourth graders, eighth graders, and high school students.

And so that is something that teachers can share with their students and they can learn about the various folks who lived and worked and participated in civic life in the Santa Monica area who were African American pioneers of various decades.

CUNO: Now, there’s also a time capsule involved. Tell us what’s in the time capsule, called Belmar 2020.

JEFFERSON: So in the time capsule, there’s a lot of different things. They got some letters from different people about what they hope will be in the future, when they pull out the time capsule in 2070. There’s a youth high school student project that was done, where kids imagined what that area might have looked like in 2020, had it remained a place where businesses and residents were; and if the beach service businesses had been able to remain there, what they might be contributing to the area. There’s a copy of the essay that I did for the project in there. There’s a copy of my book in there.

There’s some photographs that community members offered up, as well. Some artwork from some of the kids who were involved, some of it’s poetry, some of it’s more of expository writing about what they saw for the future of this area, had it evolved, in terms of being a place that was a resort area that African Americans were developing at that point in time.

CUNO: What’s the future for these leisure sites and others like them?

JEFFERSON: Most of these African American leisure sites, in terms of their current configuration, they’re not what they were in the past because times have changed. With discrimination being lessened and African Americans having more opportunities to go to lots of other places, they did, and they stopped going to some of these early resorts that they had established. And white folks never supported Black businesses, so that’s another reason why they failed.

And times change, in terms of tastes, as well. So for instance, people were going to Lake Elsinore, Black folks and white folks; but that lake situation there was precarious because the water wasn’t stable. Some years, there might just be mud there. And they didn’t stabilize the water, really, until the nineties. And now, people aren’t interested so much in that kind of recreation in the way that they were early in the twentieth century, going to a spa there, using that lake, when they can get on the freeway and they can go to the beach.

The beaches now have become more places where many people can get to in their cars. They don’t have to take public transportation. We have a more informal way in which we dress so we get in our car, we might have our bathing suit and some shorts on, and you can get there in thirty minutes, so you don’t have to go down there and stay the night, necessarily.

And then Val Verde, that was a small community up in northern L.A. County. It was originally called Eureka Villa. They built a public park there, from the 1920s to the 1940s. And that community is still there, but it’s not a resort community anymore; it’s more of a suburban community. The park is there and the swimming pool is there, and it’s a great amenity for the region up there, but that particular space is kind of hidden away in a little canyon. And the area has developed dramatically, in terms of that northern L.A. County area, and there’s other parks that people can go to that have resources, as well.

So those Black businesses have faded. But that doesn’t mean that they aren’t still inspirational stories, from the standpoint of looking at in spite of the fact that African Americans were facing discrimination, they took what was available to them at the time to try to build businesses, build communities, and enjoy what California had to offer.

CUNO: What is your ultimate goal in the work that you’re doing now?

JEFFERSON: In terms of the work that I’m doing as a historian, I’m interested in educating people. I’m interested in them learning about these stories that I have written about in my book, so that they can gain a broader sense of who we are as Americans. A lot of times, people don’t think about African Americans in the context of the American story. And so with that, I hope that these stories will engage a broad array of people to think about themselves differently.

I hope they’ll be inspired by the knowledge and empowered in their lives, whether it be to go and learn how to surf or hike up a mountain or become a civic leader. And I’m hoping that these stories that I have uncovered and reinserted into the American narrative will do these things.

CUNO: Well, your book tells a fascinating and sometimes troubling story about this racial and cultural phenomenon little known to us, I’m afraid. Thanks so much for bringing it to light and for preserving it. It’s an important story, and thank you again.

JEFFERSON: Thank you very much for inviting me to participate in your programming today.

CUNO: This episode was produced by Karen Fritsche, with audio production by Gideon Brower and mixing by Myke Dodge Weiskopf. Our theme music comes from the “The Dharma at Big Sur” composed by John Adams, for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003, and is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday, subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other podcast platforms. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts and if you have a question, or an idea for an upcoming episode, write to us at podcasts@getty.edu. Thanks for listening.

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

ALISON ROSE JEFFERSON: The reason why African Americans began these places of leisure and relaxation...

Music Credits

“The Dharma at Big Sur – Sri Moonshine and A New Day.” Music written by John Adams and licensed with permission from Hendon Music. (P) 2006 Nonesuch Records, Inc., Produced Under License From Nonesuch Records, Inc. ISRC: USNO10600825 & USNO10600824

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.