Subscribe to Art + Ideas:

“I had heard the tale and knew what to expect, but it was by far the most damaged painting I had seen. When it arrived, it came into the studio and the damage was almost all that you could see.”

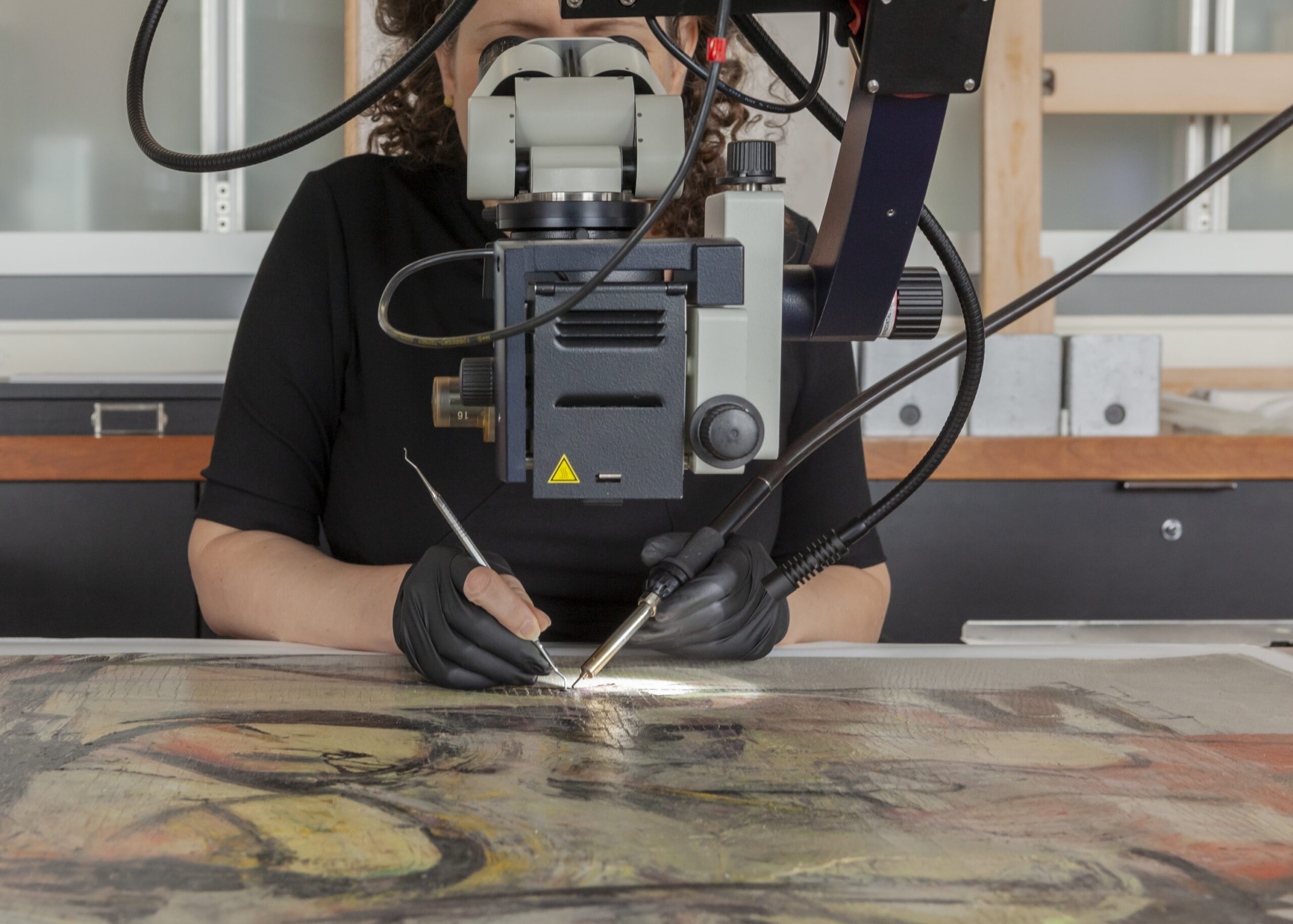

In 2017 Willem de Kooning’s painting Woman-Ochre (1955) returned to the University of Arizona Museum of Art (UAMA) more than 30 years after it had been stolen off the gallery walls. Because the theft and subsequent treatment of the work had caused significant damage, the UAMA enlisted the Getty Museum and Getty Conservation Institute to help repair the painting. When the work arrived at the Getty in 2019, the damage was so extreme that it was all paintings conservator Laura Rivers could see; prominent cracks and flaking paint obscured the artwork itself. Rivers worked alongside her colleague Douglas MacLennan, a conservation scientist who used advanced analytic methods like X-ray fluorescence and microfade testing to inform their conservation work. The results of their multi-year collaboration are finally on view in the exhibition Conserving de Kooning: Theft and Recovery.

In this episode, Getty Museum conservator Laura Rivers and Getty Conservation Institute scientist Douglas MacLennan discuss their work conserving Woman-Ochre, which is on display at the Getty Center through August 28, 2022.

More to explore:

The Recovery and Conservation of a Stolen de Kooning listen to part 1

Conserving de Kooning: Theft and Recovery explore the exhibition

Transcript

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

LAURA RIVERS: I had heard the tale and knew what to expect, but it was by far the most damaged painting I had seen. When it arrived, it came into the studio and the damage was almost all that you could see.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with Getty Museum paintings conservator Laura Rivers and Getty Conservation Institute scientist Douglas MacLennan about Willem de Kooning’s Woman-Ochre.

In 1955, prominent abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning painted a bold and expressive painting titled Woman-Ochre. Thirty years later, in an act of thievery, the painting was cut from its frame, ripped from its backing, rolled up, and stolen from the University of Arizona Museum of Art. In an astonishing incident of good fortune, the painting was recovered thirty-two years later in 2017.

Getty Museum senior paintings conservator Ulrich Birkmaier and Getty Conservation Institute head of science Tom Learner, together with Getty Museum conservator Laura Rivers and Getty Conservation Institute scientist Douglas MacLennan, led a multi-year campaign to conserve and analyze the painting. The results of this complicated treatment went on view recently at the Getty Center.

I spoke with Laura Rivers and Douglas MacLennan about their work, as we stood before the painting in a Getty Museum gallery.

Laura and Douglas, thanks so much for speaking with me on this podcast episode. Laura, we’re here talking about Willem de Kooning’s 1954-1955 painting, Woman-Ochre, which was cut and ripped from its frame by an unlikely pair of thieves, Rita and Jerry Alter. Give us a brief sketch of the theft and why the painting came to be treated by the Getty Museum and the Getty Conservation Institute.

LAURA RIVERS: On the day after Thanksgiving in 1985, a couple entered the University of Arizona Art Museum. And it was very early in the morning. She stayed downstairs and spoke with the guard, and he went upstairs. And at that point, he must’ve had a box knife, and he sliced the— I actually have difficulty talking about this.

At that point, he sliced the painting, or attempted to slice the painting from the frame. And it must’ve been a very stressful moment. He didn’t make it all the way through both canvases. And the painting did not come away, as he probably expected, and he made the choice in the moment to pull the painting from the lining. And that resulted in more damage than would’ve otherwise occurred.

When the painting was recovered in 2017, a group of colleagues who are specialists in de Kooning’s work gathered at the University of Arizona and evaluated the painting and considered what next steps should be. And ultimately, in part because of work done by Susan Lake and the GCI here, the decision was made to approach the Getty.

CUNO: Yeah. And you mentioned that the GCI—that’s the Getty Conservation Institute—and you and Douglas—Douglas being a scientist at the institute—have very different expertise. You’re a paintings conservator and Douglas is a conservation scientist, as I said. Give us a brief account of what you do as a conservator; and then Douglas, tell us what you do as a conservation scientist.

RIVERS: I think the wonderful thing about both of our positions is that we work very closely together. I am a paintings conservator, which means that I study and come to understand the paintings, with the long-term goal of caring for them and preserving, and if needed, treating them, in accordance with the artist’s original wishes, to the extent possible.

CUNO: Douglas?

DOUGLAS MACLENNAN: My background actually is in paintings conservation, so I feel a lot of the similar kind of ethical guidelines as Laura here just explained. However, I’m not working in a vacuum. And most of my colleagues actually are PhD chemists or physicists. So we really rely on each other’s varying expertise and background to sort of approach these research questions and research projects.

The GCI as a whole has a wide remit, in terms of conservation and our contributions to the field. But the department that I’m involved in, the Technical Studies Research group, our remit is really to support the work of conservation studios, both here at the Getty Museum as well as abroad, on collaborative projects that we do.

Myself, I look primarily at paintings or painted objects. And we study the different materials of artists, the different techniques. We look at the degradation phenomenon of different painting materials from antiquity all the way, in the case of de Kooning, to the 1950s.

CUNO: Okay, let’s get to the painting itself. Laura, describe for us what the painting looked like when you first saw it.

RIVERS: It was noisy, actually.

CUNO: What do you mean noisy?

RIVERS: It was visually noisy. The fragmentation of the paint surface had been so tiny and complete in many areas that there was a scattered field of small fragments across the surface. And that created a kind of visual noise that made it very difficult to focus on the image and on the painting.

CUNO: What do you mean by small fragments?

RIVERS: Literally small fragments of paint that had come away from the canvas as the painting was being pulled from the lining.

CUNO: Yeah. How did you first respond to the painting then? I mean, I have an image of it being rushed into an emergency room, strapped to a hospital gurney.

RIVERS: I first saw photographs while at a lining workshop in Maastricht. And it was alarming. I had heard the tale and knew what to expect, but it was by far the most damaged painting I had seen. When it arrived, it came into the studio and the damage was almost all that you could see.

CUNO: Yeah. Douglas, how did you first respond to it?

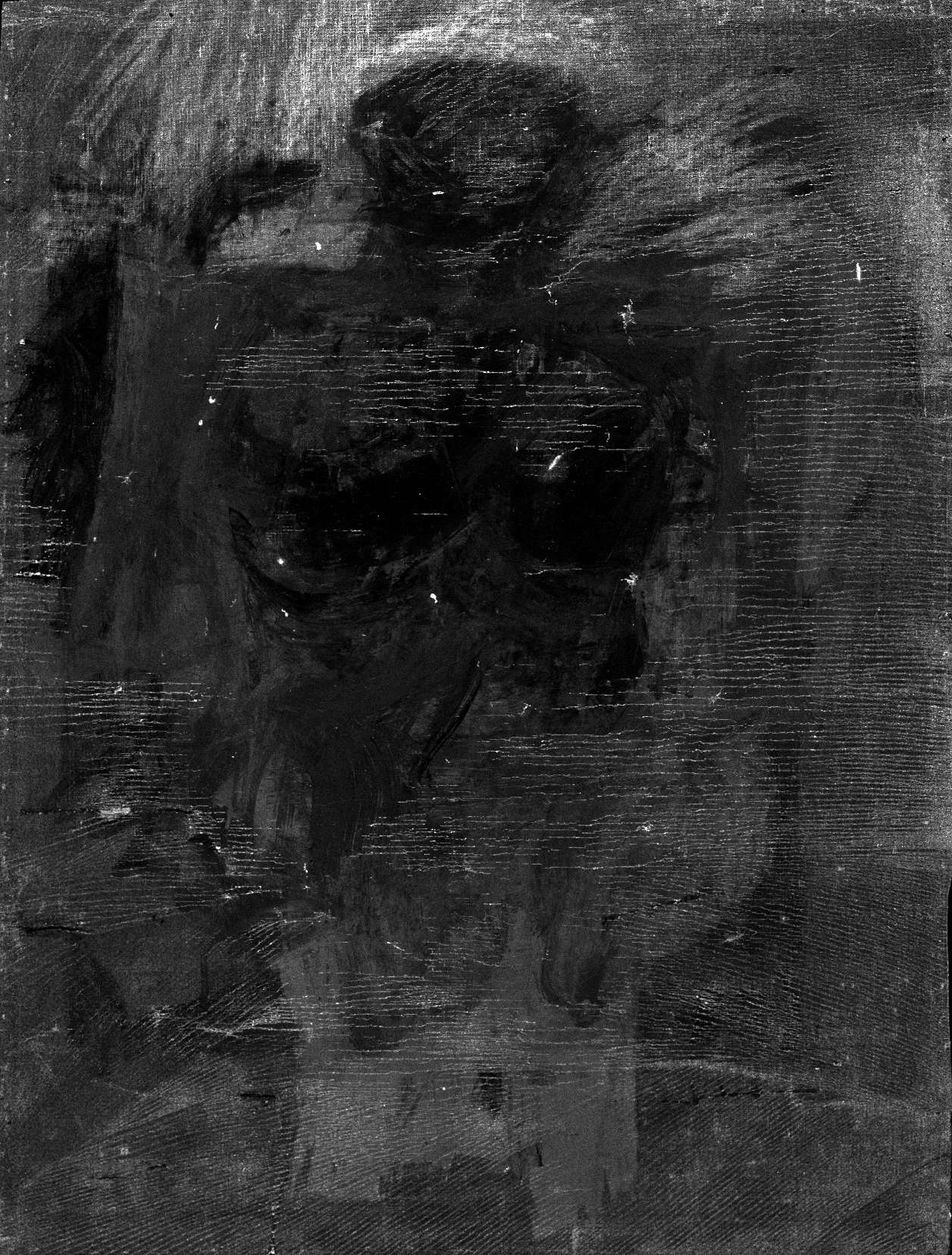

MACLENNAN: So my first response to this painting was also a little bit of shock.

CUNO: How much of a shock?

MACLENNAN: I think that the first thing that struck me was the fact that the painting looked so unlike a painting, as it was cut from the rest of itself. So the bulk of the pictorial frame that we see, back then, was completely separated from the tacking edges and the margins. And to the side, on another table, if I remember correctly, was the auxiliary supports, or the lining canvas from MoMa.

And seeing just the painting loosely unstretched on the table, with all of these highly disturbing horizontal and angular cracks throughout, breaking up the composition, it lent a sort of image of violence in my mind that was really striking.

CUNO: So you, Laura, started working on the painting right quite soon after its arrival here at the Getty. And Douglas you came in later into this. How did you soon begin to work together on the project? And what did it mean to work together?

MACLENNAN: So I actually came into this research project towards the end, in a way. And I had the luxury of starting my work based on the results of the work that my colleagues had already carried out. And that would include Kristen Watts, from the University of Arizona, at that time a PhD candidate; as well as my colleagues in GCI Science, specifically Vincent Beltran, Joy Mazurek, and also Lynn Lee.

Joy Mazurek, she’s an expert with organic analysis, using various chromatography techniques. And she had studied with Laura, many samples from the painting all throughout, to look at the binding media that de Kooning had used, and had created a really useful report, which acted as a sort of guidepost for some of the work that I was doing later on.

My other colleague, Lynn Lee, she had also collected some samples from the painting to be analyzed by a different technique called Raman spectroscopy. And my other colleague, Vincent Beltran, did what’s called microfade testing on many of the different colorants, the early days of this project. And the results from his work gave us a good idea of the light sensitivity of some of these pigments, and even a understanding of potentially measuring what their sensitivity might be looking forward in the future.

CUNO: And Laura, we’re standing front of the painting now. Describe it for us.

RIVERS: De Kooning did a series of Woman paintings beginning in 1948, and returning to the subject again and again into the 1960s. And this is one of those paintings. It depicts a woman almost enthroned. And it’s very liminal, sort of bordering between abstract and the figurative.

And de Kooning regarded these paintings as wonderful tributes to women, as the opportunity to sort of put them forth and consider all the idols of women throughout the ages. In fact, they were actually very controversial at the time, both because his colleagues in the Abstract Expressionist movement felt he’d stepped away from the abstract mission, and also the nascent feminist movement found them somewhat disturbing.

CUNO: Yeah. Now, conservators typically consider the treatment history of a painting before beginning additional treatment. Describe for us why you work this way and how it informs your response to the painting.

RIVERS: When we begin a conservation treatment, we undertake a great deal of looking and a great deal of research. Understanding what the painting has been through and what it is composed of and how it was made is crucial to the process of designing a treatment going forward.

In particular, a wax resin lining, which can so shift the fabric and shift the paint, in some cases flattening the paint, is a really significant occurrence in the life of a painting, and it’s crucial to understand. Additionally, when the painting was at the Museum of Modern Art in 1974, they also made the choice to varnish the painting. And that was a decision that de Kooning had never made. So that was the first time that varnish was on the surface.

CUNO: You mentioned MoMA. In 1974, MoMA treated the painting, or approached the painting for treatment. Tell us about that and why that was important to this project.

MACLENNAN: So other people could probably speak to the MoMA treatment much more than I; but as I understand it, the painting was lined in 1974, while it was at the MoMA. And they used a wax resin adhesive. And that auxiliary canvas is still here as part of the show this morning, just on that wall over there.

CUNO: Yeah. Laura?

RIVERS: So the painting was actually damaged while it was on tour in 1973. And the decision was made to send it to the Museum of Modern Art. And at that time, they made the choice to line it and varnish it. Lining, at that point in time, was a fairly standard practice. And while it’s not a choice that we might make today, it was done with the best of intentions. And a secondary canvas was infused with wax resin, the painting itself was infused with a wax resin adhesive, and the two were fused together.

CUNO: What does it do to line a painting? How does it help?

RIVERS: In many respects, it can save or stabilize a paint surface, depending on the state of the painting before. It also changes. It changes the movement of the canvas; it changes, in some cases, the translucency of the canvas. Wax resin can make a canvas slightly more translucent. It can change the colors of the paint, as the wax resin moves through to the surface.

CUNO: I gather there were specific goals for the present treatment. What were those goals, and why these particular ones?

RIVERS: Very specifically, the first priority was to stabilize the really fractured, fragmented surface. And the bulk of the conservation treatment, almost two years of pandemically-extended time, involved taking those fragments and working under the microscope to secure them back to the canvas and ensure that they would remain there.

The next goal was to remove the varnishes. A varnish had been applied in 1974, at the Museum of Modern Art. Another varnish had been applied after the theft. And those had significantly altered the surface. And of course, the obvious goal was to reunite the painting with its former tacking margins, with its original tacking margins, and reestablish the original format of the painting.

CUNO: Now, another way to ask the question might be that important at the early stage in treating it—the painting, that is—was consolidating the paint’s surface. Why is that so important? And describe for us what’s involved in such consolidation.

RIVERS: The paint was literally coming away from the canvas. And the presence of the varnishes actually saved much of it. The varnish applied in 1974 was almost sticky at room temperature. So when the painting was stolen, many of the fragments became embedded in the varnish. Under the microscope, very slowly over time, I looked at each individual fragment. And using dental tools and a small amount of heat, set it down, sometimes only doing an inch or so a day.

CUNO: How did you keep track of all the fragments?

RIVERS: I actually began to use a series of bedazzling boxes, the kinds of box—

CUNO: Bedazzling boxes?

RIVERS: Yes.

CUNO: What does that mean?

RIVERS: Bedazzling boxes are the boxes that you use if you’re interested in beading or in adding crystals to your cellphone case. And they are these wonderful plastic boxes that can be purchased very inexpensively on Amazon. And through the good graces of the GCI, specifically Joy Mazurek, we were able to determine that this plastic was not giving off phthalates, and would not impact the analysis. So I was able to use them and still preserve the samples for study.

CUNO: Douglas?

MACLENNAN: At this point of de Kooning’s career, he’s really experimenting with a lot of different paints—artist paints, house paints, exterior sign paints, et cetera. And if these boxes that Laura’s talking about, these bedazzling boxes, might contain any of these chemical markers for certain types of binding media—in this case, maybe phthalates—then it might give Joy a false positive; and therefore, we may misinterpret the type of paint that is in this painting.

CUNO: Now, we were just talking about the consolidation of the painting. How did the consolidation affect the appearance of the painting?

RIVERS: It dramatically reduced the visual noise. So in addition to sticking down the paint that was still semi-attached—and all of this is happening under a microscope—I was also gathering up fragments that had just scattered across the surface, and using these small boxes and a gridded-out image of the painting to sort of locate them and record when I had found them.

In some cases—very few cases, a few times a day—I was able to put a fragment back where it actually belonged, maybe an inch or two from where it originally had been. So in many respects, this was the smallest jigsaw puzzle I’ve ever worked on, and also the largest.

CUNO: Yeah, I can imagine. What about scientifically examining the painting? How do scientists see paintings different than, say, conservators?

MACLENNAN: So the science on a picture like Woman-Ochre is really, really complicated. Looking at this painting here in the gallery now, you can see there are yellow paints mixed with red paints, mixed with orange paints and brown and white and black. And as an analyte that presents a lot of challenges. de Kooning was never kind of reusing the same tricks twice. And he’s changing his technique depending on the types of materials that he’s using, depending maybe on the mood of the day; it’s hard to say.

But in the case of this painting, approaching it from the scientific perspective was a real challenge. And one of the benefits that we have at the GCI is the expertise from so many different people. So this was a team effort, like a lot of science. And because of that, we were able to divide a very complex problem into more manageable pieces and start to answer questions and build up a model of what we’re seeing here this morning, from a material point of view.

RIVERS: I think what’s really extraordinary about this project is that Conservation and Conservation Science really came together in the best way possible. And the treatment, in many respects, could not have been carried out without the work that was undertaken by the GCI. We often work on paintings in tandem; but this is the ideal example of how one affects the other so dramatically, how the science really drives the treatment.

CUNO: Now, as part of the treatment of the painting was the cleaning of the painting. What was involved in cleaning this particular painting, and why is it cleaned, and what role does that play?

RIVERS: There were two varnishes present on the painting. And that had dramatically shifted our experience of the surface, obscuring the undulation of matte and gloss that was characteristic of de Kooning’s painting at this moment in time. De Kooning hadn’t chosen to varnish the painting, and so we knew we needed to remove those. Initially, we were very concerned about the charcoal present in the paint. All of these paintings are an amazing back and forth between painting and drawing.

And he’s using both paint and charcoal, coming back and forth between the two. And so we could see fragments of charcoal on the surface, and that raised questions about whether those could be safely cleaned. Had they been saturated by varnish before? And that was initially the concern. But as is often the case with conservation treatments, it ultimately wasn’t the larger issue.

CUNO: How would I see the effects of cleaning on the painting?

RIVERS: Before the painting was cleaned, it would’ve been difficult to stand in front of it and take in the whole of the painting and be able to see the subtle differences in the paint. So the very glossy black looked much the same as the very matte and ethereal phthalo blue in the upper left corner. And that really wasn’t the case and wouldn’t have been de Kooning’s experience of the painting.

Once you remove those varnishes, you’re able to take in the velvety quality of the phthalo blue and the rich, almost dripping quality of the black.

CUNO: I gather there are sometimes concerns about removing the varnish layers of a painting. What was the concerns about removing the varnish layers of this painting?

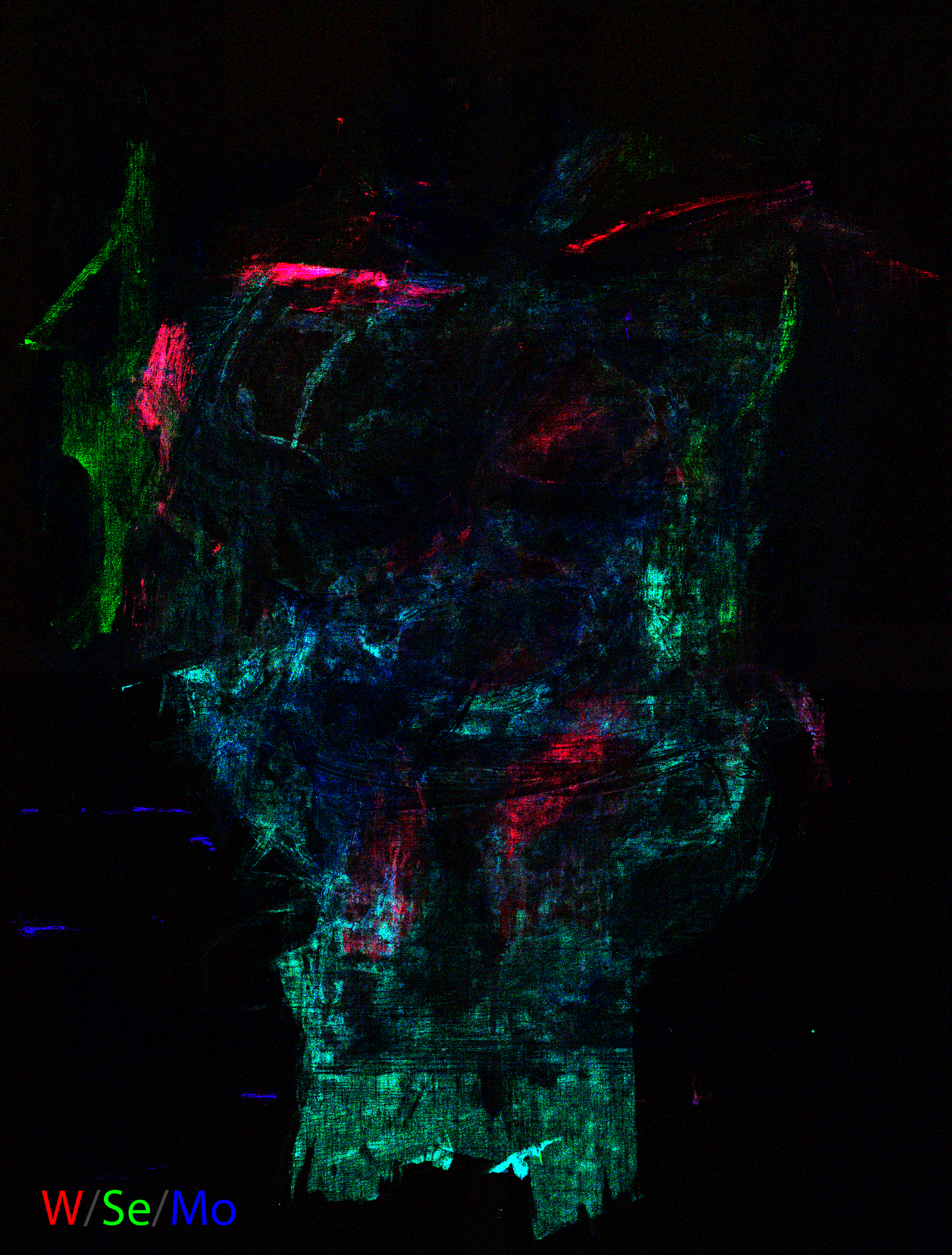

RIVERS: Yeah. So the particular issue for this cleaning really became an unusual rhodamine pigment, the hot pink that we see in the figure’s shoulders. And that was identified by the GCI, and really restricted the kinds of solvents that could be used to clean the painting.

The macro XRF was really essential to understanding where the rhodamine pigment was on the painting, and thus, to determining how exactly the painting could be cleaned.

CUNO: Now, we hear a lot about XRF, when talking with conservators or scientists about works of art. And that, I gather, is a nondestructive analytical technique. Tell us more about that—what it is, when in treating a painting do you use an XRF, and how does it affect the appearance of a painting?

MACLENNAN: Yeah, those are good questions. XRF stands for X-ray fluorescence. It’s an x-ray-based spectroscopy. As you said, it is important in our field because it doesn’t require samples. X-ray fluorescence is an elemental analytical technique. It’s based on the principle that if you expel with energy, an electron, another electron in that atom will fall, and it will replace the expelled electron. And the energy difference between the electron which was ejected and the one that replaced it is fluorescence. And that’s what we’re detecting. And that energy is characteristic for an individual element.

So if we think of maybe holding something in our hands as for an element, the energy that I, Douglas, emit would be different from the one that you’d emit. And our detector can measure those energies and we can see, either in a point or in many, many hundreds and hundreds of thousands of points, then create a map.

CUNO: What instruments do you use to look so closely at a painting?

MACLENNAN: We have a number of spectrometers in the lab. But the one that was probably the most useful for this project was an instrument manufactured by a company, Bruker, in Germany. It’s a X-ray fluorescence spectrometer which is connected to a motorized gantry. And we collect measurements on the fly in a raster scan. Maybe for de Kooning, a couple million points. Put those points together, look at them from a perspective of, well, I’d like to see just this energy for copper or for tungsten or molybdenum or titanium. And then see the distribution of that element all across the entire painting. And you can imagine as a visual map, how powerful that is.

CUNO: Yeah, I can imagine. What about microfade testing? What is that and how do you use it?

MACLENNAN: Microfade testing is another important analytical technique that we use on painted surfaces. Vincent is our resident expert, so I wish he was here this morning to explain the technique in a much more sophisticated way than I am able to.

But as I understand it, it involves taking a very, very small area of what you’re measuring and exposing that to light, and measuring just the first perceptible change. And comparing that to a set of well-known standards, you can extrapolate on the sensitivity of that material to light. And what’s really, really powerful about MFT, microfade testing, is that it’s one of the very few techniques that we’re aware of that allows you to say in the future, this material—for example, the bright red pink in the de Kooning, which is a rhodamine pigment—PR81 is its kind of industrial name.

It’s a phosphotungstomolybdic acid. And it is, what we found, the most light-sensitive pigment in this painting. It’s likely already changed. We have a little bit of evidence to suggest that maybe the paint was located and still visible in more areas of the woman we don’t really see anymore. But we know, for example, that its light sensitivity, as predicted by MFT, microfade testing, would suggest that in the future, the custodians for this painting should be somewhat mindful of its exposure to light.

CUNO: Now, while you’re in the laboratory doing this kind of work and Laura’s in the conservation laboratory, the studios, how are you communicating to each other and on what regular basis do you do so?

RIVERS: There is a door between the two spaces, and we regularly run back and forth through that door. So it is literally a daily conversation. And that is the most extraordinary and amazing thing about working here.

MACLENNAN: So the Technical Studies Research Lab, although it’s part of the GCI, we’re in the museum envelope and we’re in the same controlled environment as the museum conservation studios are. And our lab is designed, in a way, for paintings or any objects to be brought to the lab. So very critically, paintings don’t just leave the museum for analysis, but they can come to our lab. And our proximity geographically within the museum allows us to have really a daily kinda check in, and keeping each other apprised of what’s going on.

CUNO: One other source of information that you used was the written or vocal evidence of de Kooning’s intentions in his paintings, from art historians and from de Kooning himself. Tell us about that.

RIVERS: So de Kooning’s descriptions of his own working process are generally limited to comments in interviews, comments with artists. And they have filtered through the art historical literature. And in some cases, ideas that were correct at one point in time are applied to the whole of the career. Or ideas that actually were somewhat erroneous persist throughout the literature, and they’re repeated.

At a certain point, Susan Lake, who’s both a conservator and also a PhD technical art historian, undertook a major study of de Kooning’s work, looking at a number of paintings, primarily in the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, and engaging with the materials—which in some respects are the most powerful primary sources.

CUNO: Yeah. De Kooning was famously an expressive painter, once saying, “When I think of painting today, I find myself thinking that part is connected to the Renaissance. It’s the vulgarity and fleshy part of it which seems to make it particularly Western.”

How are we certain that with all the scientific equipment and treatment of the painting that you’ve applied, that we’re not losing some of its vulgarity and fleshy part?

RIVERS: I think standing in the room, it’s fairly strongly still there. Additionally, the science really serves to understand the artist in a way that we can’t otherwise, particularly in circumstances where they didn’t leave the kinds of clues about, or the kinds of statements about their work that we as conservators would love to have.

CUNO: So what do you do to keep the hand of the artist visible in all of this process?

RIVERS: Understanding the materials and understanding how they might’ve appeared when de Kooning finished the work is really crucial to understanding what the goals are for the treatment.

During a conservation treatment, there’s an extraordinary moment, during visitors begin to come to the studio and not immediately see the damage; they begin to see the painting again. And that is really when we know that we are approaching the end of the treatment.

CUNO: Yeah. Now, the painting is currently on view in the Getty Museum’s galleries. What will people be expected to see in the galleries?

RIVERS: We hope that they will see the painting first, and that they will see the painting and not immediately focus on its terrible history.

When you walk into the galleries, the painting is on a diagonal wall. And it grabs your attention immediately. To the left, there’s a wall describing the history and the theft. Behind the painting, there’s a wall describing the Getty Conservation Institute’s work investigating the materials of the painting. And to the right of the painting, there’s a wall discussing the conservation process. There’s also a small video.

On the wall behind the painting, there’s a photomural showing de Kooning in his studio, and a case containing a number of materials from the studio.

CUNO: So what do we and the painting’s owner, the University of Arizona, hope the public will get from seeing the conserved painting?

RIVERS: I hope they get to see a de Kooning, and to see a painting from the Woman series, and to not immediately walk in the room and be cognizant of the damage that happened in the past.

CUNO: Douglas, what about you?

MACLENNAN: I agree with Laura. The de Kooning painting looks so striking on the white walls of the gallery here, which is a little uncommon for the exhibitions that we typically have here at the Getty Center. And in terms of the material presented around the painting, I think the objects from the studio, I would hope, might lend a sense of intimacy for the viewer, to see the kinds of materials that was de Kooning was working with, the kinds of tools that he used to create these varies of effects that we see in Woman-Ochre and in so many of his other paintings.

And also, I think that it gives visitors a chance to see kind of behind the scenes in the museum. So to understand the different questions and the different problems that we as conservators and conservation scientists and all types of roles have, when it goes into preparing these exhibitions.

CUNO: And what’s next for the painting after that exhibition? It will be on view for a long time at the University of Arizona, as part of its teaching mission.

RIVERS: Once the exhibition closes, it’ll be on view at the University of Arizona, where it should’ve been all along.

CUNO: Yeah. Well, thank you both for speaking with me today. It’s been an illuminating conversation for me, for certainly. So thank you again.

RIVERS: Thank you. It’s been a pleasure.

MACLENNAN: Thank you very much.

CUNO: Willem de Kooning’s Woman-Ochre is on view at the Getty Center through August 28, 2022.

This episode was produced by Zoe Goldman, with audio production by Gideon Brower and mixing by Mike Dodge Weiskopf. Our theme music comes from the “The Dharma at Big Sur” composed by John Adams, for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003, and is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday, subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other podcast platforms. For photos, transcripts, and more resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts/ or if you have a question, or an idea for an upcoming episode, write to us at podcasts@getty.edu. Thanks for listening.

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

LAURA RIVERS: I had heard the tale and knew what to expect, but it was by far the most damaged pain...

Music Credits

“The Dharma at Big Sur – Sri Moonshine and A New Day.” Music written by John Adams and licensed with permission from Hendon Music. (P) 2006 Nonesuch Records, Inc., Produced Under License From Nonesuch Records, Inc. ISRC: USNO10600825 & USNO10600824

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.