Subscribe to Art + Ideas:

When Brigitte Benkemoun bought a leather diary case from eBay, she did not expect to find a small address book tucked into the back. And she certainly didn’t expect that book to contain the names of some of the most renowned figures of 20th century Paris—names like André Breton, Brassaï, Jean Cocteau, and Jacques Lacan. She began researching these contacts until she uncovered the identity of the address book’s former owner: the surrealist artist Dora Maar.

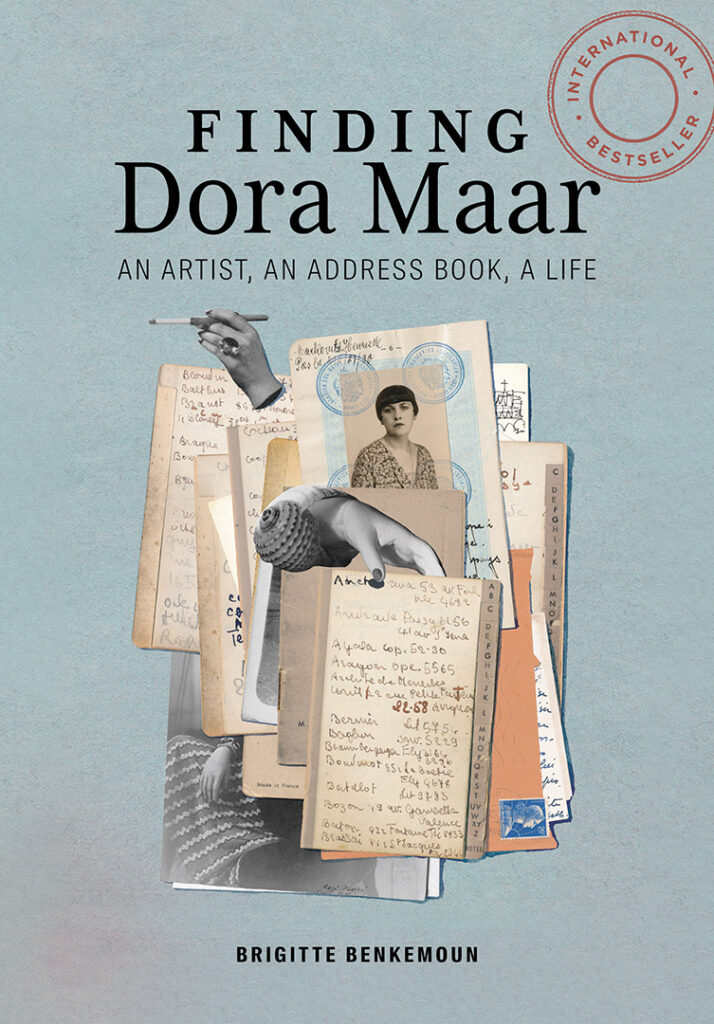

In this episode, Benkemoun discusses the provocative life of Dora Maar and the book that resulted from her research, a unique blend of detective story, biography, memoir, and cultural history. Finding Dora Maar: An Artist, an Address Book, a Life has recently been translated into English by Jody Gladding and published by Getty Publications.

More to explore:

Finding Dora Maar: An Artist, an Address Book, a Life

Transcript

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, President of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

BRIGITTE BENKEMOUN: It was amazing, so many genius within twenty small pages. It seemed to me obvious that the owner was a genius, too, but I didn’t know who it was.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with writer Brigitte Benkemoun about her new book Finding Dora Maar.

Dora Maar, French photographer, painter and poet, was born Henriette Theodora Markovitch in Paris in 1907. For most of the next twenty years she and her family lived in Buenos Aries, returning to Paris around 1926, when she enrolled in the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs and the Académie Julian.

Nine years later, Maar exhibited with a group of Surrealist artists, including Salvador Dali, Max Ernst, Man Ray, and Yves Tanguy. And in 1936 she photographed Picasso in her studio and began a tortured romantic relationship with him. Picasso painted a series of portraits of her, known as “The Weeping Women.”

In 1951, Maar kept a small diary and address book noting her activities and relations with a number of artists. Sometime and somewhere, it dropped from sight. Then decades later, Brigitte Benkemoun’s husband, Thierry, bought a vintage diary on eBay and it turned out to be Dora Maar’s address book, and which gave Brigitte all she needed to write a compelling and intimate book: a glimpse into the life of one of the greatest surrealist photographers of all time.

That book, Finding Dora Maar: An Artist, an Address Book, a Life, has been translated into English and published by Getty Publications. I recently spoke to Brigitte about this book and Dora Maar’s life.

Brigitte, welcome to the Getty podcast.

BENKEMOUN: Thank you.

CUNO: Now, tell us about the 1930s, when Dora Maar was a fashion photographer, commercial photographer, street photographer, art photographer, collage photographer, and seemingly, every kind of photographer all at the same time.

BENKEMOUN: It was such an incredible decade, such a creative time. Surrealism, modern art, cinema, photography, psychoanalysis. Paris was the place to be, where everything happened. But it wasn’t as funny as the previous decade, les années folles. Paris was not only a moveable feast, as Hemmingway wrote, Nazism, fascism settled in Europe; and on the other side, communism, artists and intellectuals were very, very politically active on the left, as Dora was.

At the beginning of this decade, she was a young photographer. But she was already working for press, fashion, advertising, as you say. She earned money. She was able to share one of the most beautiful and modern studios in Paris with a friend. And around 1933, she became Bataille’s lover. She met Breton, she got involved in Surrealist groups. Her friend’s names were Éluard, Breton, Clousseau[?], Cartier-Bresson, Prevaire[?]. Under their influence, she understood photography could be art, not only commercial.

She experimented Surrealist collage. She traveled alone in Spain, in England, reporting in poor neighborhoods, taking pictures of poor people, victims of the crisis. So beautiful, successful, politically active, with the most incredible friends you can imagine at this time. And then she met Picasso, the most famous painter of the century. Indeed, it’s quite a decade for her.

CUNO: Exactly. And it happened so quickly, it seemed, because she only came back to Paris in 1926; only six or seven years later, she was in the center of the Surrealist art community. How did it happen so quickly for her?

BENKEMOUN: I think you have to imagine a very ambitious woman. She was ambitious for her career, for her artistic career; but she was ambitious, too, for relationships. She wants to meet the more intelligent, the more genius people who were in Paris by this time. And so everything went very quickly.

CUNO: And equally quickly with Picasso. She meets Picasso, and she begins a close relationship with him almost immediately, it seems, not only taking his picture in the studio, but also taking pictures of him painting Guernica, the great painting in opposition to the fascists in Spain. How did that relationship start so quickly and proceed so dramatically?

BENKEMOUN: I think it wasn’t so quick, because they meet at the beginning of 1936. And they were not lovers immediately. We don’t know exactly when they began to be lovers, but at the beginning, Picasso was absolutely fascinated by her. For the first time in his life, he was in love with an artist, an intellectual, a very, very intelligent woman. But after a few months, as he starts to become tired of such a bright woman—don’t forget he was Spanish, born in nineteenth century, a terrible macho. So he needed to dominate her, humiliate her, crush her.

And the love story evolved into a sadomasochistic relationship, and she accepted the lot of things. But you’re right; Guernica was indeed a very special moment in their relationship because Picasso accepted what he never accepted before. He let Dora took pictures while he was painting, from the beginning to the end of Guernica, one month. My feeling is that she thought she was painting with him, because she was looking at him all day long, in total symbiosis.

It was probably a big misunderstanding with Picasso. He only needed her pictures. He never admitted she helped him, not even to encourage him to denounce the Guernica massacre. But after Guernica, and maybe because of Guernica, Dora Maar renounced photography and decide to became a painter.

CUNO: So let’s get back to her painting, because she painted throughout her life. But there’s a concentration of paintings in the 1940s, after this great decade of the thirties. And these are paintings that one would say are dark, empty paintings of the World War II years, followed, in the 1950s, by abstractions and photograms. What was Dora Maar’s life and career like in 1951, the year of the address book we’re going to be talking about?

BENKEMOUN: Yes, you’re right; the war period and the break up with Picasso in 1944 has been terrible. She even had to be interred in psychiatric clinic, where they use electroshock. That’s why her first paintings during and just after the war are so dark. But in 1951, after six years without Picasso, six years with Lacan, she started to feel better.

In 1951, she had almost completely recovered her mind and her social life. She shared her time between Paris and Ménerbes. She became very religious, but not as fanatic as she will be later. And she was painting, moving away from the pictorial influence of Picasso she had at the beginning. Her paintings were still figurative. They will become abstract later, photogram even later. She was painting, but without selling anything. Maybe one painting from time to time. But when she needed money, she rather sold one of their Picassos.

CUNO: Now, I asked about 1951, because that’s the year of the address book. So tell us about the address book. Describe it for us and how it was that you found the address book.

BENKEMOUN: Oh, I have it in my hand. I knew you [would] ask me about the address book, so I took it. It’s a small leather case. The leather is soft, smooth. It’s almost the same [as] my husband had before, just a little it more reddish. And when you open it, alas, there is no more diary inside. But still a very small address book. On the first page, Aragorn[?], Breton, Brassai, then Braque, Balthus, Cocteau, Éluard, Lacan, and so on.

At the end of the address book, you have a calendar of 1952. So you can imagine it was bought in 1951.

CUNO: Tell us how it came into your hands. I know your husband got it on e-Bay and so forth, but how quickly did you realize you had something quite special in your hand?

BENKEMOUN: I realized I had something special when I saw Cocteau. Because I began to leaf through the notebook without being very attentive, only by curiosity. However, on the third page, Cocteau really startled me. Then all the other names came. It was amazing, so many genius within twenty small pages. It seemed to me obvious that the owner was a genius, too, but I didn’t know who it was.

CUNO: Would it have been different if it had been a 1950 address book? In other words, did she change it from year to year to year?

BENKEMOUN: I think she may add people, maybe erase some names when she didn’t want to see people. I have seen in her archives, some other address book and diary. Some people are always the same. But some are people that she knew at the beginning of her life, and some at the end of her life.

CUNO: And so you’d have the name of someone, a friend of hers, and a location underneath the name or next to the name, from which you could begin to put together a narrative story. The first chapter deals with Bergerac. Tell us why and what happened there.

BENKEMOUN: Yes, Bergerac, because the first person I asked about the address book was obviously the person who sold it [to] me on e-Bay. And she is an antique dealer. And she told me she bought the leather case in an auction in Sarlat. Then she found out that the first dealers were coming from Bergerac. So why Bergerac?

Unfortunately, the auctioneer, never accepted to give me the name of the people who sold the diary. So I bought an old telephone book to compare each name, each number. After that, I was sure she was a woman, she was a painter, close to Surrealists, patient of Lacan. And finally, thanks to one name, architect of Ménerbes, on the first page, I found out, this clue indicates she used to live in a small village in South of France, Ménerbes. So Bergerac was a wrong track, but wrong track part of life, part of a book. And it was important for me to write this story as I truly lived it, as a real investigation.

CUNO: Well, four chapters later, the main figure is Jacqueline Lamba, Dora Maar’s oldest friend, who’s identified in the address book—or at least that’s what you first thought. Tell us about that.

BENKEMOUN: Yes, I had no doubt when I saw Lamba on page L, because everywhere in biography, you can read about their friendship. Dora Maar and Jacqueline Lamba were students together in art, and then Jacqueline married André Breton and Dora Maar became Picasso’s lover. The story is well known. So I began writing about that. But very quickly, the gallerist Marcel Fleiss sent me a message. He told me, “There is a problem with this address. Lamba never lived Sept square du Rhône.”

So I was very surprised, but I searched again on the internet, and I discovered that the person called Lamba in Dora Maar’s address book not Jacqueline, but her sister. that’s the beginning of another story.

CUNO: Yes, tell us about that, ’cause I had never heard of Huguette Lamba.

BENKEMOUN: Nobody has never heard about Huguette Lamba because she’s not famous at all. She was the older sister, but the most fragile one. She was teaching the piano, but wasn’t a great pianist. I was about to give up this path when I realized how interesting it may be. Because in Huguette got pregnant when Jacqueline and Breton left France to take refuge in New York during World War II. Jacqueline asked Dora to take care of her sister, alone in Paris, and she did.

She even took care of the baby. And unfortunately, the baby died. Both women were devastated. Dora and Huguette Lamba. This story could be anecdotal, but it really touched me, for two reasons. First, Jacqueline’s letter was sent from a very small fishing port in Algeria. Not a random village, but the one where I grew up. It was just incredible for me.

Second surprise, I found out that the baby’s name was Brigitte. Believe me, I’m usually very rational, but at that time, I was absolutely stunned.

CUNO: Yeah, almost as if the address book was meant for you to have.

BENKEMOUN: Yes.

CUNO: What about the poet Paul Éluard?

BENKEMOUN: Paul Éluard was a great poet and a very close friend of Dora Maar. He was a member of the Surrealists group. He was there when she met Picasso, because by this time, he was Picasso’s best friend, best poet friend. You know, Picasso always needed a poet around him. He had Appolitaire[?], he had Max Jacob, he had Cocteau. By this time, it was Paul Éluard.

And so they were together when Picasso met Dora Maar. Then they went on holiday all together several times in South of France, in Mougins. Picasso, Dora, Éluard and his wife Nusch, Man Ray, Ady, Penrose, and Lee Miller.

They call themselves la famille heureuse. That means happy family. And Éluard had great respect for Dora’s work and he really loves her. I’ve seen some letters, some cards. They have a very deep friendship.

CUNO: And what role did he play in the relationship between Picasso and Dora Maar?

BENKEMOUN: As I told you, he was here when Picasso and Dora Maar met at Café Les Deux Magots. Maybe he helped Dora Maar meeting Picasso, because he was convinced Picasso needed a bright woman, an intelligent woman, an artist, not only women he had before, who were not very intelligent and not artists at all.

CUNO: Was he someone who could help her in times of trouble for her, because he had her trust, as well? In other words, was his friendship equally with Dora Maar and Picasso, or was he able to help Dora Maar in times of trouble when she was having difficulties with Picasso? Or was he more closely related to Picasso?

BENKEMOUN: He was friends with both Dora and Picasso at the beginning. And you know, Éluard was a notorious libertine. For him, fidelity in love was not very important. He often shared his wife with Picasso, as he used to share his first, Gala, with Max Ernst. But when he realized how Dora Maar was suffering in this relationship, especially when Françoise Gilot arrived, he was the only one to help Dora and blame Picasso.

After the breakup, he tried to remain close to her and to Picasso. But she became very religious and he was a member of the Communist Party, as Picasso, so inevitably, they moved away from each other. And Éluard died in 1952. But when she was suffering he was the only one to help her and blame Picasso.

CUNO: Yeah. What about Jean Cocteau? What was his relationship with Dora Maar? And what was the group’s experience of the German occupation? Because it was difficult, I know, for Cocteau.

BENKEMOUN: Jean Cocteau is not as Éluard. He was only interested in Dora because of Picasso. She took pictures of him before she met Picasso. But he was incredibly fascinated by him. Maybe in love with Picasso for years. When you read his war diary, some sentences are just crazy. Picasso and Cocteau had been angry for several years before World War II.

Thanks to Dora, they became friends again during occupation. In 1942, they used to have lunch or meet every day. And Cocteau was so happy to be with Picasso to speak about painting, art; not only war. So when Picasso left Dora for Françoise Gilot, he simply left her, too. I don’t think she was fooled by him. She knew he was just a charming opportunist.

CUNO: But what about the German occupation?

BENKEMOUN: I think they felt like they were resisting, because they stayed in Paris. But they were not resistant at all. They only stayed in the middle of Paris, with Germans around. They tried to have fun sometimes, they tried to meet friends, they tried not to feel too bored. It wasn’t very courageous resistance. It was just a period where they tried to live, to go on living.

CUNO: Well, I know that at the same time, she was friends with Michel Leiris, who was a great poet and ethnologist. And again, it was at the time of the German occupation that continued to sort of influence their relationship or their lives together.

BENKEMOUN: Michel Leiris was a great ethnologist and writer and poet, close to Bataille. And then very close to Picasso. He adored him, too. It’s fascinating how Picasso was adored by a lot of men. Men were fascinated by him, as Cocteau, Leiris. So many men loved him. And Leiris wasn’t very interested in Dora Maar. He found her very snob, not natural. In his diary, he wrote she was “déguisée.” That means in costume, not authentic, not natural.

He probably never realized how terrible was her life with Picasso. As Cocteau, he hasn’t seen her much after the breakup. Most friends turn away from her, when she was no more Picasso’s favorite. And as Éluard, he was close to the Communist Party. He was resistant, a little bit resistant during the occupation. And he didn’t understand how religious she became.

CUNO: Well, is it about the same time that she makes friends with Jacques Lacan, the psychoanalyst? At the time in which she suffered from these psychotic episodes. What about that relationship with Lacan?

BENKEMOUN: Yeah. I’m not sure they were really friends. They lived in the same community. They are friends with the same people. But I think— You know, in French, you say, tu when— that means you, when you’re really friends. And you say vous when you are not “intime.” Or I don’t know how to stay that.

CUNO: Intimate, yeah.

BENKEMOUN: Intimate. And Lacan and Dora always say “vous.” She knew him, especially when she was mad and very bad. When they met, he was a young psychiatrist, close to the Surrealist circles. He only started working around the theories of Freud. And he knew Picasso very well because Picasso called him when something hurts, he called Lacan. For everything. Fever. Anything, he called Lacan.

And when Dora Maar had a nervous attack in a restaurant in 1944, Picasso and Éluard immediately call Lacan, who took her in the clinic and treated with electric shock. It seems very strange today that he did so, but at this time, even Lacan considered electroshock as a miracle cure for mental illness. Then Dora started after that, a serious analysis with Lacan, which lasted six years. She stopped just after the 1951. Just after the address book, when she became very, very religious.

And as their mutual friends were wondering how such a brilliant woman became so fanatic. Lacan answered, “It was God or straightjacket.” It was very interesting for me to discover with Dora, the beginning of Lacan’s career. Before he was a psychoanalyst star.

CUNO: Then there was the Viscountess Noailles, who with her husband, would become the greatest art patrons of their time, with works from Goya to Chagall and Picasso, and from her father’s collection, Rembrandts and Rubens. What was the relationship between Dora Maar and the Viscountess?

BENKEMOUN: They were friends. It’s— I’m not sure of the word. But in fact, yes, they were friends.

Marie Laure de Noailles was a very paradoxical woman. Very intelligent, very cultivated. She was indeed, with her husband, the most incredible art patron of this century. They supported Picasso, Dali, Balthus, Bunuel, Cocteau, Chagall. But she could also be terrible, manipulative, selfish, snob. She became close to Dora Maar during the World War II, because they were both in Paris during the occupation. They felt anxious, lonely, bored. Afraid, because Marie Laure de Noailles’s father was Jewish. And Dora Maar has a Jewish name. She wasn’t Jewish, but she had a Jewish name. So they were both very anxious about that, and they helped each other.

Everything was different in 1951. At this time, she organized dinners, parties that were very famous. She invited artists in a wonderful villa in Hyères. Dora was often invited with a friend, Balthus or with American James Lord. But sometimes she wasn’t invited, just because Marie Laure was suddenly fed up with her or wants to punish her for something she didn’t like. And as with Picasso, Dora Maar, even she had quite accepted the whims of Marie Laure, until Dora stopped seeing people, all her friends, around 1958.

CUNO: And then there was the English art historian and the great Picasso and Cubist scholar Douglas Cooper. Tell us about him.

BENKEMOUN: It’s an incredible person. He was paradoxical as Viscountess. At the same time, a great specialist in Cubism, intelligent, funny, but also terrible, mean. When he got mad with him, Picasso called him Dégueulasse Cooper. Not Douglas Cooper, Dégueulasse Cooper. And dégueulasse means disgusting.

He pretended to appreciate Dora, and invited her very often in his wonderful house in South of France. But he was mostly interested by the Picasso paintings she owned, and wanted to buy them. I met John Richardson, famous historian, who was at this time Cooper’s companion. I met Richardson just before he died. And he still remembered everything, almost every person in the address book. And he told me something very important.

He told me, “You won’t understand Dora Maar if you forget she was, above all, masochistic.” I still remember that, because I think it’s a key, a very important key to understand who she was.

CUNO: Now, the final chapter in the book is about Dora Maar herself. And I’m remembering now that I didn’t ask you about the change of her name. Because Dora Maar was not her real name, but she changed it to Dora Maar. Why did she change it, and does that mean anything?

BENKEMOUN: Her real name was Theodora Markovitch. I think she first changed because she wanted to have an artist’s name, and Theodora Markovitch is too long, so Dora Maar. When she was young, everybody called her Dora. And she choosed Dora Maar because it was an artist’s name, it was a fine name. And above all, maybe, she didn’t want people to call her Markovitch because Markovitch was sometimes a Jewish name. And she became more and more afraid of this name. We can understand why she was afraid of this name.

CUNO: Now, as I said, this final chapter dealing with her was very personal with you because you stayed in her house, you lingered outside her studio, you even meditated at her grave. What was the house like, and what was it like for you, after training down so many people, so many places important in her life, to come back home to her house?

BENKEMOUN: It was very touching. Writing this book was, for me, like a journey in Dora’s world, in Dora’s life, meeting Dora’s friends. And the purpose of this journey was to meet her. And when you travel in a country, you don’t visit all the cities. So I didn’t explore, as well, all the names I found in the address book. I have so many regrets, if you know. I regret Braque, I regret Chagall, I regret [inaudible], Giacometti. Maybe one day, a volume two. But I’m sorry, it’s not your question.

It was very touching to stay in her house, sleep in her room. Just one floor about a whole room. Wake up with the same amazing view in the [inaudible]. I don’t know if you have been there. It’s so wonderful. I think I understood her painting at this moment.

When I went to the graveyard where she rests, close to Paris, it was something else. I just wanted to say thank you. Thank you for the journey, thank you for the people I met thanks to you, thank you for the miracle of this book.

CUNO: Well, tell us about your translator, Jody Gladding.

BENKEMOUN: I didn’t know her. And we still never met now. But it’s incredible. It’s a miracle. The book is a miracle from the beginning to the end, because Jody was in Dora’s house in Ménerbes, with an artist’s foundation now. And she was studying, writing there. And director of this house, gave her my book and told her, “You should read that.”

And Jody read my book in Dora’s room. And she loved the book and she sent me a mail asking if she could try to translate it. So I was delighted. And everything goes on. So it was a miracle. Jody was in Dora’s room writing my book, and then talking about this book to Getty Publications.

CUNO: Well, it’s beautifully translated.

BENKEMOUN: Oh, thank you very much.

CUNO: And it’s haunting and beautiful, and we thank you for joining us on this podcast to talk about the book. I should ask you if you’ve purchased anything on e-Bay recently.

BENKEMOUN: I tried to book another one for my husband, just for— Because I was afraid he’ll lose this one, too. But there was nothing inside; I’m so sorry.

CUNO: Well, maybe the next time, there will be. So thank you so much, Brigitte, for talking with me on this podcast.

BENKEMOUN: Thank you very much.

CUNO: This episode was produced by Zoe Goldman, with audio production by Gideon Brower and mixing by Mike Dodge Weiskopf. Our theme music comes from the “The Dharma at Big Sur” composed by John Adams, for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003, and is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday, subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and other podcast platforms. For photos, transcripts and more resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts/ or if you have a question, or an idea for an upcoming episode, write to us at podcasts@getty.edu. Thanks for listening.

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, President of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

BRIGITTE BENKEMOUN: It was amazing, so many genius within twenty small pages. It seemed to me obvio...

Music Credits

See all posts in this series »

Can’t wait to read Brigitte’s book! Doesn’t the Getty have Douglas Cooper’s papers?

John Richardson was Picasso’s definitive biographer, but I think he passed, just last year, before completing the last volume…

Thank you for the article on Dora Maar—I had just read about her in Picasso latest book—at any rate after I tracked her down, I got the book—it is good!

Tanks.

Connie