Subscribe to Art + Ideas:

“When I look at the law and also museum policy, it’s just so close to conceptual art making. You have a lot of material and you’re just trying to define how it lives in the world, except with the law, everybody agrees. With conceptual art, you have to convince people to believe in it.”

Gala Porras-Kim is an interdisciplinary artist whose work is both conceptually rigorous and visually compelling. Born in Bogotá and based in Los Angeles, Porras-Kim creates art that explores the relationship between historical objects and the institutions that collect and display them. From writing letters questioning how museums handle artifacts to creating sculptures that honor the spiritual lives of antiquities, Porras-Kim’s practice is part concept, part material manifestation.

The artist’s current exhibition, Precipitation for an Arid Landscape, focuses on the Peabody Museum’s collection of thousands of artifacts originally found in a giant sinkhole: the Sacred Cenote at Chichén Itzá on Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. The exhibition is one in a series of solo shows at the Amant Foundation in Brooklyn, Gasworks in London, and the Contemporary Art Museum in St. Louis. The work is based partly on research Porras-Kim carried out while she was a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies at Harvard and an artist in residence at the Getty Research Institute.

In this episode, Porras-Kim muses about rummaging through museum archives, the rights of mummies, and potlucks in the Pink Palace.

More to explore:

Meet the Getty Research Institute’s Newest Artist in Residence learn more

Precipitation for an Arid Landscape explore the exhibition

Transcript

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

GALA PORRAS-KIM: When I look at the law and also museum policy, it’s just so close to conceptual art making. You have a lot of material and you’re just trying to define how it lives in the world, except with the law, everybody agrees. With conceptual art, you have to convince people to believe in it.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with artist Gala Porras-Kim about her experience as Artist in Residence at the Getty Research Institute and her current exhibition Precipitation for an Arid Landscape.

Gala Porras-Kim, Artist-in-Residence at the Getty Research Institute, is an interdisciplinary independent artist based in Los Angeles. Her work explores the social and political contexts that influence how language and history intersect with art.

Her current exhibition, Precipitation for an Arid Landscape, is based in part on research undertaken while being a Fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies at Harvard University and as Artist in Residence at the Getty. It is organized and produced by Amant in cooperation with KADIST and is curated by Ruth Estévez and Adam Kleinman. I recently met with Gala at the Getty to talk about her work.

Thank you, Gala, for speaking with us on this podcast.

PORRAS-KIM: Thank you for having me.

CUNO: Now, you were born in Bogotá, Colombia. Give us a sense of your background and your early experiences with works of art.

PORRAS-KIM: My parents were both historians, so growing up in Colombia, they took me to a lot of historical museums. And I think that most of my early memories of dealing with art were at really colonial-style museums and back of churches, because in Colombia, the archives are mostly in the back of church. And so while my dad was working, I would just hang out with the painting part of it. And it’s always been kind of figuring out how artwork exists with research at the same time.

CUNO: You knew that already then, that you were interested in the topic.

PORRAS-KIM: Yeah, I think that my dad was always a hobbyist artist, so he really encouraged me to look at artworks, since I was two. When I was younger, we moved around a lot. And so he would encourage me to make a museum of the moment in which we lived in a specific city. And then we would go through the motions of collecting and deaccessioning things because there was not enough space. And so I think early enough, he was teaching me the ways that institution works already.

CUNO: Yeah? Well, when did you come to US?

PORRAS-KIM: I came when I was twelve, ’cause my mom was going to getting her PhD at UCLA at the time. And so I moved in ’96.

CUNO: What drew you to the visual arts as a student or a young person?

PORRAS-KIM: I think I thought that the arts was the broadest field, because I was always really interested in, like, history and conservation and museum studies; but in a sense, I really don’t like writing at all. And so the idea of having an academic job alone, where the main medium is writing was very discouraging. So I thought maybe with the arts, I would have more freedom, in terms of medium, and not so much like a preset methodology of how things were supposed to be presented in the public.

CUNO: What was your experience like at UCLA and CalArts?

PORRAS-KIM: I think they were very different. I think with education in undergrad and grad school is a little bit different, because at UCLA, you kind of get a sense of the different mediums that you could work in. You know, like, sculpture, painting, photography, beause you haven’t really decided which field you want to go into. You sorta have to study all of them to see which medium is the one that you like the most or fits better. And I think at CalArts, it’s mostly like a conceptual frame of mind. So once you have all of this material study, then you can decide, what is your work about? And so in a sense, it’s more like beyond the material making of something, what are you gonna make work about? And so the different focuses of the schools were really complementary to each other.

CUNO: What artists were influential in your early work?

PORRAS-KIM: I think the artists that I worked with at CalArts were the most influential because I think maybe it was the beginning of figuring out what my own practice was gonna be like. And I worked a lot with Harry Gamboa and Michael Asher and Charles Gaines. And so those, I’d say, would be the ones that I really looked at the way that they thought about their subject and the way that they lived their own life, and how they interacted with their students, that I wanted to sort of follow.

CUNO: And do you consider yourself a graphic artist or a conceptual artist? Or is there a distinction between the two?

PORRAS-KIM: I think I would say that I consider myself both, because the idea might start with a conceptual framework, but in a sense, I feel like I’m still attached to a material manifestation of a work. You know, I think at CalArts, it was very immaterialized, ’cause it was very conceptual-focused. But in a sense, I always thought that that would limit the public in which my work could reach. And in sense, I wanted, honestly, to have my mom bring her friends and be like, ‘I understand something,’ instead of not being able to see anything at all.

CUNO: How was it that it was so conceptual at CalArts? What do you mean?

PORRAS-KIM: I think in CalArts, you didn’t actually have to know how to technically make anything physical. It was mostly looking at the frameworks of objects and material and in the world. So mostly systems and immaterial things, which also build material, but not in a physical sense. It’s the formal descriptions of a work beyond the material shapes. Like the biography of an author and how that also informs a work, or the way that the material is presented in a institution and how that frames a work. So something that is not technically a physical, malleable, immediate thing, but more the system around things that would shape it.

CUNO: How many fellow students were there at CalArts?

PORRAS-KIM: I think in my class, there were thirty of us total at the time.

CUNO: So you had a lotta people exchanging ideas?

PORRAS-KIM: Oh, yeah. I think so much about school is so dependent on the cohort that you’re in. I think we were really competitive with each other. And so there was this lecture series on Thursday, for example, that there was an invited artist, and we would all prepare on Thursday day to figure out what the hardest question we could ask, and then see. Just try it out live. And so in a sense, the conversations that we had through that speaker, but essentially with each other, was the actual learning part.

CUNO: Did museums matter to you then?

PORRAS-KIM: I think museums didn’t really matter then so much, because when I was a student, it was hard to imagine what it would be like to participate in the bigger art world. You know, so you’re just thinking about how to just form material in the studio to begin with. And then once you graduate, it’s like, oh, well, what is the deep vault of art history and then you have to think about the institution.

CUNO: Yeah. What about your experience here at the Getty?

PORRAS-KIM: The first time I came here was when I was thirteen. And so I have been here throughout my whole life. One of my first jobs was at the research institute, as an assistant. And then later, when I had my first project with the Fowler Museum, I also thought a lot about conservation. And so I worked with some of the conservation institute people to try and just frame ideas that I didn’t know. I feel very lucky to be so close to the Getty, because my kind of hometown resource for informing my own work has been here.

CUNO: Yeah. Now tell us about your experiences at Harvard, where you were a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

PORRAS-KIM: I think that the Radcliffe was the first time that I did a year-long research program, where I looked at the collection of the Peabody Museum. And so it was one of the first times I was really able to go into a collection and understand not just the topical aspect of how it exists within the collection. I think with art making, some of the ideas just take such a long time to stew or come up out of just browsing. And so the longer you can browse, the more subtle connections you can make with the subject.

CUNO: Yeah. Now, the Peabody Museum is an anthropology, right?

PORRAS-KIM: Right.

CUNO: How do they have such a program? Or did they just open their doors and you walked in?

PORRAS-KIM: The Peabody collection is, because it’s a university museum, it’s supposed to be a research institution. And so it’s available for students to go and look through the collection and I don’t know if they have anything you can’t see, really. And so as a research institution, it was open for me to ask for a lot of information about the specific objects that they had from Chichén Itzá. So they have the main collection of objects that were dredged from the Cenote at Chichén Itzá there, which were the ones that I was looking at, at the time.

CUNO: Did you go in looking for them, or did you just stumble upon them while you were there?

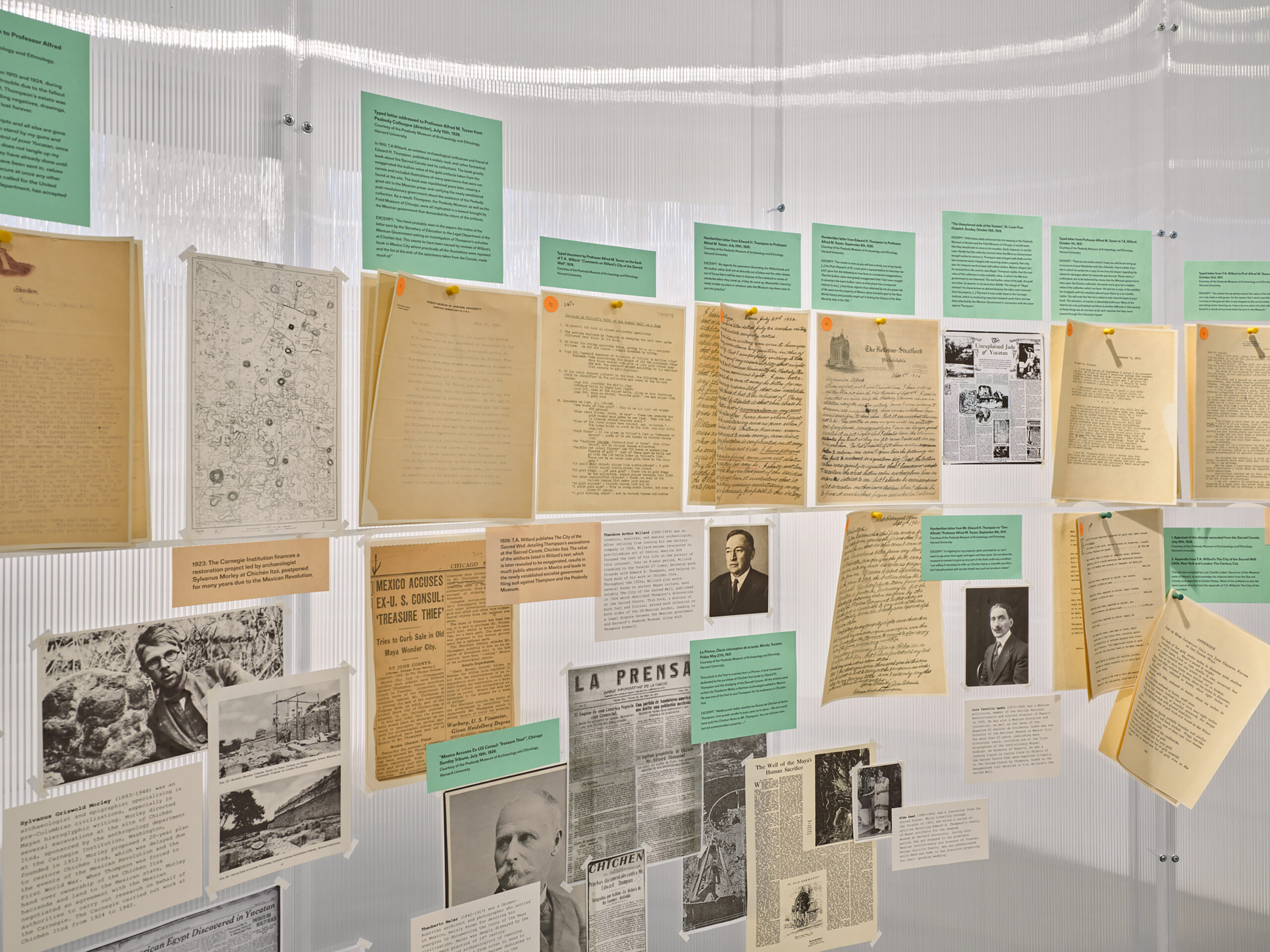

PORRAS-KIM: I knew they were there, ’cause it’s one of the most important Latin America collections in the US. And at the time, I was looking at how regulation and law shapes the way that objects exist in collections. And the Peabody, having objects from Chichén Itzá, so much of the way that they got there was through these legal moves that this guy Edward Thompson did with the director of the Peabody.

So I really just went reading their mail for most of the year, really, to just sort of understand how it was that they went from one place to the other. When I look at the law and also museum policy, it’s just so close to conceptual art making. You have a lot of material and you’re just trying to define how it lives in the world, except with the law, everybody agrees. With conceptual art, you have to convince people to believe in it. But specifically, what was interesting about that project was that those objects were votive offerings to the Mayan Rain God, and now that they were in the Peabody collection, because of conservation, they’re in the driest place possible. And so the idea of something that is meant to be submerged in water now being in the most driest place is kind of something I wanted to look more into.

CUNO: Now, you made a number of works based on museum collections, by drawing them and mounting them on canvas. What prompted you to make them that way?

PORRAS-KIM: I think drawing as a medium just allows for a very slow understanding of an object. It’s kind of a way to slow down my own time, because my attention span is so short that with drawing, I really have to slow the pace of looking at something. You know, photography might be quicker, but the way that I can understand a object by staring at it for so long I think is a specific type of learning that you can’t really get through reading about an object.

CUNO: Did you draw at the Peabody itself, or did you draw in a studio?

PORRAS-KIM: Because of COVID, I ended up having to change the way of working. I was originally gonna draw them there, but then the ones that resulted were from the online catalog. And so the project became something about the process of cataloging and photographing an object when it’s not accessible to a public live.

CUNO: You’re attracted to the history of colonialism. Why does art help you in this work, if it does?

PORRAS-KIM: I think colonialism is a very big word. And it really manifests itself in so many different ways we might not be able to see, even. And so I think through art making, I want to see how the things that I experience in the day-to-day in a collection or something not necessarily exist in the—what we think colonialism is in the historical past, but like a version of it that is invisible. And we might necessarily not be able to cancel it altogether, but how to address it so it’s not pretending like it’s not there.

CUNO: Were you aware of it when you were a child?

PORRAS-KIM: I definitely was aware of colonialism as a child, because my dad taking me to all of these archives for super-Spanish colonial things. And so all of the documents that he was reading were mainly just Spanish accounts of the colony. One of the more clarifying moments I had was when I went back to school at UCLA after CalArts, to do a MA in Latin America studies. And at the time, I worked with Kevin Terraciano, who was writing the history of the colony from the indigenous point of view. And so in my mind, it was like, I can’t believe that I didn’t even think that there was another version of the history of the conquest that came from the indigenous point of view. It’s so clear that there’s two sides, and the fact that I didn’t see it made me worried.

CUNO: Worried about what?

PORRAS-KIM: Worried that there were so many obvious things that you couldn’t see.

CUNO: Yeah. Now, you gave an interview where the interviewer asked you if you were advocating for the rights of the public or of objects in your work. That struck me as an interesting question.

PORRAS-KIM: I think that the object is just material to really take into account all the stakeholders that might have on that material, that might not even be alive today. So I think that when looking at an object, you really take into account not just the public that lives with it, but also any other public that might have seen it in the past. Or the author of the work or the person who thought that that material would do something in perpetuity. So in a sense, it’s not thinking about a specific object or a specific public, because each object has such different circumstances for it.

CUNO: Who should govern access to works of art? And on what terms should they determine such access?

PORRAS-KIM: That depends on what the work of art is. I think that if it’s an antiquity or a contemporary work of art, the access would be different. I think that with antiquities, the public that’s meant to look at it varies so much. Whereas with contemporary art, it’s easier to see who that public might be. And so who should govern it depends on who was meant to look at it to begin with.

CUNO: Does it matter whether the works or cultural phenomena in question are transboundary structures or in structures in danger?

PORRAS-KIM: Again, I think that it just depends on the specific object. Each one has such different circumstances in which it was made, that would determine how it is that they might be dealt with or who has access to it or who takes care of it. Because I think that maybe what I like about looking at collections is that it sort of levels out all of the things inside of the building, when each one of those objects inside of the museum have so many different circumstances that are almost impossible to keep track of.

And so whether a work is endangered or crosses boundaries, you’d have to say think through so many contingent things. Like, was the original country even there when that object was made? Like, does the state that an object is returned to gonna be able to care for it or not? Should the object be existing to begin with or not? There’s so many different circumstances to take into account.

CUNO: What about the difference between works of art and human remains, in terms of access, in terms of governance of the purpose of the art?

PORRAS-KIM: I think about this question a lot, because they are parallel, but not the same. I feel like when I make a work, it’s kinda like my baby. You know, a lot of my work stems from the worry of what is gonna happen to this work when I’m not here. Like, who will care for it? Where is it gonna be shown? Is it gonna be at the thrift store? And can I pick which thrift store it’s gonna be at? But I think with a body, since we don’t know what actually happens in the afterlife, I would choose to plan for all of the possibilities of that original person and what their beliefs for their own material was. You know? I think that it changes so much culture by culture. You know, I just came back from studying the mummies at the British Museum. And because the Egyptians planned for their afterlife so hard, they literally live longer because they’re on view in our minds everywhere else.

Whereas cultures who might not have planned for their afterlife are not here anymore in our minds, in the institutions, or in the books, or really not so much. It’s interesting to think about how the regulations over different corpses or mummies or dead people, changes over time or country or institution, really. When I was making a project for the São Paulo Biennial, I made a work with the oldest mummy in the Americas, which is Lucia. Called Lucia. Somebody named her Lucia.

And I was talking to the national coroner of Brazil about when a dead person becomes old enough to stop being a cadaver and start being an object in a collection. ’Cause the regular actually changes. Cemetery rules versus mummy rules are different. And so I was just thinking, like, freshly-dead people have different rights than older dead people. And so he went and gave me a five-hour lecture on just the updating of Brazilian law and how it changed over time. And so it was just interesting to see how, like, people’s material changes just in every country, and institutional policy over it.

CUNO: Yeah, that’s a strange concept I’ve never thought before, is that mummies have a different sort of standard to a dead person.

PORRAS-KIM: Yeah. Like, a fresh dead person would never be on view, you know? It was funny because some of his advice was like, ‘If you don’t wanna be on view, then you wanna make sure that you get buried in a wet spot, so the maggots eat you, so then you don’t become jerky and then become a mummy.’ I was like, ‘Okay, thank you.’

CUNO: Keep it in mind.

PORRAS-KIM: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

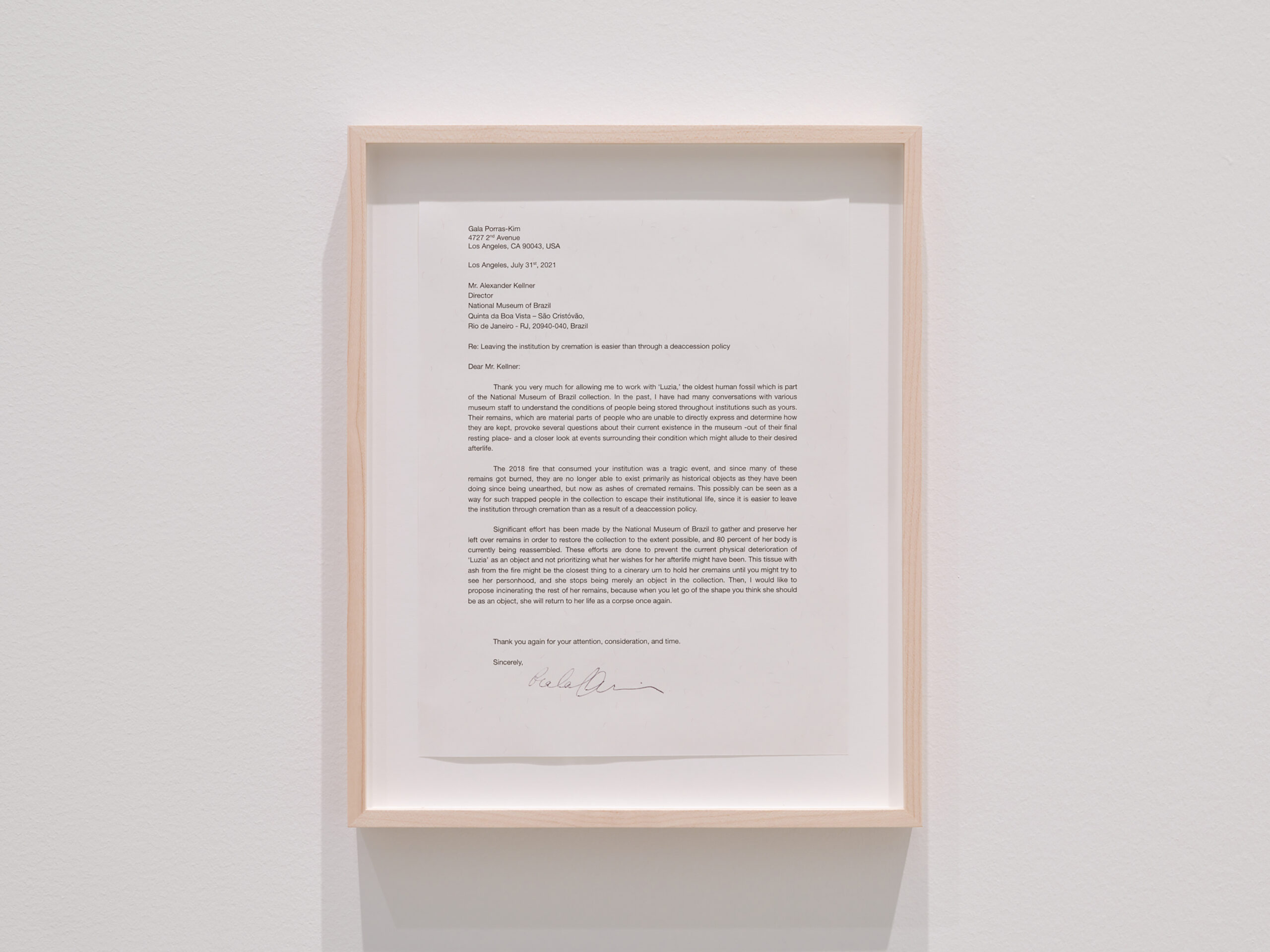

CUNO: Tell us about the museum in Brazil.

PORRAS-KIM: Ah, yeah. The project that I did with the museum in Brazil was with the anthropology museum in Rio that caught on fire. And so I was thinking about Lucia, the oldest mummy in the Americas. And so I was thinking, like, if that was my mom, what would I want for it? Or what would she want for herself, you know? At the same time, I was thinking a lot about deaccession and different ways of deaccessioning that are not through regular policy. And so I thought that since the fire that burnt most of the museum actually burnt 20% of Lucia, that could’ve been a way of deaccession, through cremation. And so the letter that goes along with this napkin of ash that I collected after the fire, I was thinking about this ash being like a cinerary urn and the fire being just a way to escape the museum that is not through deaccession policy.

CUNO: What’s the fate of the museum now? How is it?

PORRAS-KIM: I don’t know the whole museum, but I know with Lucia, they collected 80% of her body and they’re trying to put her back together. I think that with those works, I don’t actually know which way is right or not. And so I think that’s why I want to make works about them, because there is no resolution; it actually feels right both ways.

CUNO: What do you mean?

PORRAS-KIM: Feels right to try and preserve her historically, but feels right to burn the rest of her body, to make her not be there anymore. So the name of that work is, Leaving the Museum Through Cremation is Easier Than Through Deaccession Policy.

CUNO: It’s a terribly funny but sad at the same time.

PORRAS-KIM: Because it’s funny and sad at the same time.

CUNO: Yeah. Now, you’re an artist in residence here at the Getty. What’s your project?

PORRAS-KIM: I actually have been at the Getty for two years now, because of COVID. And so my original plan was to come look at the Stendahl Archive. Because you had just gotten the papers for the Stendahl Archive. And at the time, I’m looking a lot about just art and law and regulation of West Mexico ceramics in the US, et cetera. Not necessarily really have a project in mind, but just browsing, same as when I did at the Peabody. And also, I wanted to spend a lot of time in the conservation institute, because a lot of the museum policy is framed around material conservation. You know, like, how can an object exist is really contingent on material preservation. But sometimes it’s difficult to think how a scientific method could be overlaid over something that’s a cultural object. That might be changing.

Maybe the contextual function of something might be more important than its physical quality. For example, if something is meant to be decayed or submerged in water or exposed to acid, that goes so much against conservation methodology, no? And so I was just coming to browse, most of the time. And I was thinking about different ways that a specific subsection of the collection which was supposed to have an infinite function—Like in the past, it was an object that was never supposed to stop doing its original function. Like, donation to a deity is supposed to be forever. And what happens when now it’s in a collection and that function is still ongoing, within the museum? And how, through fragmentation, there could be a way in which that original function might still be able to be recaptured.

So for example, if collecting dust from a object that’s meant to be buried, and then burying that dust fragment, however minute it might be, would that still be enough to reconstitute some original function? And not get in the way, actually, of the day-to-day working of the museum. So it’s just finding how these reconstituting of original functions might not interfere with the day-to-day of the museum.

CUNO: Now, your fellow scholars come from all over the world and they spend a year here working on some project related to the theme of the year and the theme this year is the fragment. Has your being in the company of these other scholars changed your work and your thinking about your work?

PORRAS-KIM: Once we started coming to meet in person, I think that my research really changed, because to browse from the collection or to browse from your cohort’s mind is so different. And so I think that listening to the lectures that my fellow scholars are giving has completely changed the way that I’ve been looking for what I thought I wanted to see.

Since we all share the same theme, it has been really eye-opening because I’m not an art historian, so how different scholars see different forms of dealing with fragmentation. Because it’s basically how to build a historical narrative from not a whole anymore. And so I have learned so much about how, for example, the fragment of a holy site, once transferred to a museum, actually turns the museum into a new holy site, instead of the other way around. Or how to reconstruct Palmyra, when Palmyra was already fragmented. And so in a sense, it’s just these very philosophical questions that seem practical, but it’s almost impossible to actually do these things. And what I’m doing now is just laying up a lot of new ways of thinking about collections, fragmentary collections. I mean, even dust is a fragment, which I can implement in my future projects.

As an artist, I think that maybe one of my methodologies is always just to be around people who do a lotta research in the subject I want to make work about. Because there’re so many experts who’ve spent and devote so much energy in that specific research, and you can just drop in and they tell you what is interesting about their work.

And so in a sense, it’s really amazing just being around them because it’s basically just taking a lot of notes and inspiration from the fellows and future works that might come.

CUNO: Now, you work in a studio that the GRI provides. What’s in your studio now? If we were to walk over to your studio, what would we see?

PORRAS-KIM: A computer.

CUNO: A computer.

PORRAS-KIM: I have my studio in South L.A., which is the dirty, practical one. It’s a 1920s brick building that used to be a bank. And it feels like it’s messy because, you know, I make large graphite drawings, for the most part, and I would say that it’s covered in graphite all over the place. And here is the slowed-down library-style one, which I like very much. The studio at the GRI is really to slow down time again. You know, art life is just so fast and complicated that it’s difficult to find the time to actually go into depth and read and just understand catalogs, or just spend an entire week looking at TMS, which is a cataloguing system. And so it’s really just like a office in a library.

CUNO: Do people stop in and bother you while you’re working?

PORRAS-KIM: They’re not bothering me. People don’t really stop by here, because I also live in the Pink Palace, so we see each other in a private setting.

CUNO: Tell us about the Pink Palace, what that is.

PORRAS-KIM: The Pink Palace is the scholar housing. It’s a beautiful apartment complex down Sunset, where we all live, and then take a shuttle up to the Getty.

CUNO: So you sit around and make dinners and talk?

PORRAS-KIM: Yeah. So it’s such a relief to be able to do that, because during COVID, there was nothing. And so what we have planned is a weekly dinner, pot luck, after each scholar presents their paper. And so whatever the theme is, then the pot luck follows the same theme. For example, when my colleague gave a talk about fragments in Persian temples, then the potluck theme was Persian food. She gave us different easy recipes to follow. So I ended up making a salad I had never made before. And then of course, we have the most interesting conversations there, about how each other’s works might influence other’s research.

CUNO: Now, for the last couple of years, you’ve written several letters to prompt museums and archeological institutes to reconsider the way in which they make conservation and restoration decisions. Have you written the Getty Research Institute yet about this, with the same question?

PORRAS-KIM: Well, I probably will write to you at some point.

CUNO: What will you ask me?

PORRAS-KIM: I don’t know yet. I’m still looking for it. But the GRI doesn’t have a collection in itself, does it?

CUNO: It’s got archive materials.

PORRAS-KIM: The archive, yeah.

CUNO: Which relates to the work that you do.

PORRAS-KIM: Right. You know, all of the institutions that I have worked with basically have to deal with the same type of collection management questions. And many of them are about that specific subcategory of objects which is still functioning in some other capacity, and now it’s on view or in the storage of a collection. And what to do about it. I don’t have an answer. The letters are meant to just prompt conversations about it. Questions of how to keep human remains when a person probably didn’t wanna be on view for a long time. Or how to reconstruct ritual objects that might not interfere with the tourism of the Pyramid of the Sun or something like that.

CUNO: Now, I gather the Peabody Museum at Harvard is the only institute that’s responded to your letters. Does that frustrate you? Or is that part of the piece?

PORRAS-KIM: No, it doesn’t frustrate me at all. I’ve written six letters and the response has been different in every case. There has been two public programs with the people who received a letter in which we discussed questions about the collection in front of the works themselves. Or like, the public can actually be involved in asking their own questions. Because I know that for sure, I’m not the only one who has these questions. And so in a sense, it’s not necessarily manifested in a physical letter shape.

And then the other thing that I think about this response is not that they have not responded, but that they have not responded yet, because the staff will change, and then I will resend the letter, and then there will be a new frame of mind at the museum, and then maybe then there’ll be a response.

CUNO: Now, your current exhibition on the East Coast, Precipitation for an Arid Landscape, is your first solo presentation on the East Coast. Describe it for

us.

PORRAS-KIM: Okay, so this exhibition is the result of the research that I made at the Peabody Museum, with the objects that were dredged from the Sacred Cenote at Chichén Itzá, which is a naturally occurring limestone pool where ancient Maya used to donate artifacts to the Mayan Rain God Chaac.

So the exhibition in New York has three parts. And one of them is about the catalog. And so it’s a literal representation of how the objects exist in the cataloging system, drawn out. I kind of made this part just to be able to visualize what the specs of each one of the objects was, since I was not able to really see the objects in person, but through COVID, we just looked at them through the computer.

The second part is a installation, which is made out of copal, which is one of the main materials that was dredged out of the Cenote. And that is mixed with dust that we collected from the storage of the Peabody Museum, where the objects are currently stored. And the way that the installation works is that the institution in which that work is shown is meant to figure out a way to get rainwater onto that copal dust structure.

And so the work has actually been shown in multiple locations, and so there has been different ways which institutions have gotten rainwater into it. So for example, at the São Paulo Biennial, they made a condensation cube around it so it was continuously rained on. And in New York, they made a hole in the ceiling so the rainwater is dripping from the ceiling onto it. And currently, at the Radcliffe Gallery, I think that the public is encouraged to collect rainwater and then dip it themselves. So that’s the installation part.

And finally, there’s a letter exchange between myself and Jane Pickering, who’s the director of the Peabody, sort of going through different questions about conservation and regulation and how somehow, there could be a mediation between the rain and the museum.

CUNO: Yeah. So your work is so much about place, and it’s about a kind of displacement of things. What has the reception been like in the East Coast, of your work—most of which was made in the East Coast, but of course, your work is also made in the West Coast—has the reception been different, one place from another?

PORRAS-KIM: Yeah, because I lived in L.A. for so long, you know, my community of artists is really here. And so when I have a presentation here, it feels like home-team advantage or something. Whereas when I was in New York, even though it feels like it’s a bigger venue, I was really anonymous, which I really liked, because in a way, I could see the audience reaction unfiltered, since they didn’t know I was the artist. So you can just, like, go around the gallery and actually hear unfiltered review.

CUNO: Did you like what you heard?

PORRAS-KIM: Oh, yeah, yeah. Because you’re like, ‘Okay, I did a good job. Nobody’s pretending like they like it ’cause they know who you are.’

CUNO: What’s next for you?

PORRAS-KIM: So next for me, I have two shows in the fall. One is at the Fowler, at UCLA, which is a show about the overflow storage and also TMS, which is the cataloging computer system that they have. And it’s pretty much dealing with questions about how objects get inputted into a cataloging system, which might be limited in not accounting for other categories, which might be relevant to their object. And I also have a exhibition at the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo in Sevilla, in September.

CUNO: What do you hope your work will do?

PORRAS-KIM: I don’t necessarily think I can expect anything, but I think that the intention of the work is really to help people who are trying to resolve very difficult questions that almost have no answer. But I think a lot of the museum people are just kind stuck in, like, ancient methodology of the museum. You know, they inherit regulation and ways of practicing that they don’t believe in anymore or might not be updated enough or of course, there’s no deaccession policy. Like, nobody can talk about deaccession at all.

And so in a sense, it’s thinking about, the public expectation that a museum can actually care for the collection the way that we think it can be cared for is impossible. ’Cause you know, I think that the way that the— the way that people are talking about these subjects now is so polarized. It’s either ‘destroy the museum altogether’ or ‘not dig anything up at all.’ I’m trying to resolve some of those questions myself because I can understand, that the museum comes from a legacy of colonialism, but I also love going to the museum. So in a sense, I learn so much from it. I would never have seen or formed my own frame of mind without going to one.

CUNO: Thank you Gala for speaking with me today, it’s been a pleasure.

PORRAS-KIM: You’re welcome. Thanks for having me talk to you.

CUNO: This episode was produced by Karen Fritsche, with audio production by Gideon Brower and mixing by Myke Dodge Weiskopf. Our theme music comes from the “The Dharma at Big Sur” composed by John Adams, for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003, and is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday, subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other podcast platforms. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts and if you have a question, or an idea for an upcoming episode, write to us at podcasts@getty.edu. Thanks for listening.

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

GALA PORRAS-KIM: When I look at the law and also museum policy, it’s just so close to conceptual ar...

Music Credits

“The Dharma at Big Sur – Sri Moonshine and A New Day.” Music written by John Adams and licensed with permission from Hendon Music. (P) 2006 Nonesuch Records, Inc., Produced Under License From Nonesuch Records, Inc. ISRC: USNO10600825 & USNO10600824

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.