Subscribe to Art + Ideas:

Art institutions around the world responded to the COVID-19 pandemic by closing their doors and rethinking planned exhibitions, programming, and partnerships. Now, a few months into the crisis, museums are beginning to reopen, but they are also reevaluating what the next few years might bring and how they might continue to work collaboratively.

The pandemic hit just as Getty was beginning to partner with museums in Mumbai, Mexico City, Shanghai, and Berlin on its Ancient Worlds Now initiative, a ten-year project dedicated to the study, presentation, and conservation of the world’s ancient cultures.

In this episode, Neil MacGregor, former director of the British Museum, joins Sabyasachi Mukherjee, director general of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya in Mumbai, and Antonio Saborit, director of the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, to discuss their responses to COVID-19 and their hopes for the future of the Ancient Worlds Now initiative.

Transcript

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, President of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

ANTONIO SABORIT: Let’s make the most of all these reflections, considerations that we are having these days. Because these ideas are very important for the future of our museum.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with two international art museum directors, Sabyasachi Mukherjee in Mumbai and Antonio Saborit in Mexico City, about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on their museums.

A few months ago, I spoke on this podcast with museum directors from New York to Los Angeles about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on their museums. At the time, their museums were closed with no clear sense of when they might reopen. Since then, most of them have planned their reopening, even if it’s still a month or more away.

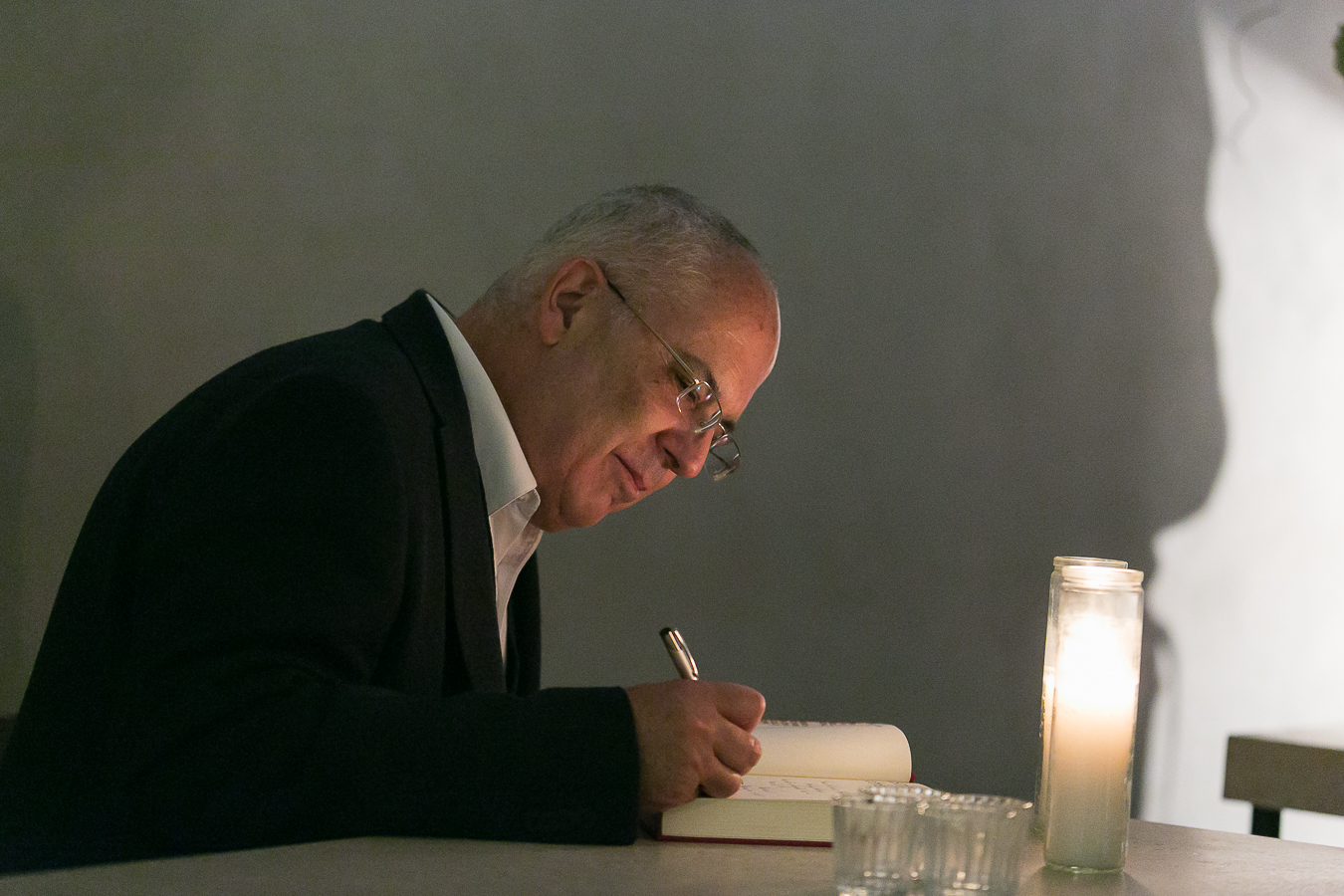

Recently, and with Neil MacGregor, former director of the British Museum, I spoke with museum directors from Mumbai, Mexico City, Shanghai, and Berlin.

Neil and I first thought we’d meet in person with these directors of prominent art and anthropology museums as part of Getty’s Ancient Worlds Now initiative. This is a ten-year, multifaceted project dedicated to the study, presentation, and conservation of the world’s ancient cultures.

And then, COVID-19 entered our lives and one museum after another shut down and remained closed for months, dimming the prospects for our initiative. But soon enough, as these museums began to discuss reopening, Neil and I thought it would be a perfect time to talk with their directors about their experiences with COVID-19, how it affected their museums and their publics, and what it means for the Ancient Worlds Now initiative.

The result is two podcast episodes: the first on Mumbai and Mexico City, and the second on Shanghai and Berlin. Because of time differences, we held the conversations with each director separately.

Later in this episode, we’ll talk with Antonio Saborit of the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

But this episode begins with Dr. Sabyasachi Mukherjee of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, formerly the Prince of Wales Museum of Western India, in Mumbai. He has been director general there since 2007. Neil MacGregor and I spoke with him on June 12.

So Mukherjee, thank you for joining us on this podcast episode. It’s been a long time since we’ve talked.

SABYASACHI MUKHERJEE: Yes, thank you. Thank you, Jim.

CUNO: Could you start by telling us about the current state of affairs in your museum, how you’re doing during the pandemic, and if you’ve had other issues to deal with other than the pandemic?

MUKHERJEE: Well, the lockdown here, it has been extended until 31st June. This is for the second time, government extended the lockdown period. And the museum remains closed to the public since 15th March. We are working, about eight- to ten-person staff, working in the museum, practically every day. At the moment, we are struggling. We are struggling here with the maintenance of building and collection. And of course, we are dealing with the budgetary deficit. That’s a huge, you know, headache at the moment.

We had a huge problem with the museum building conservation project. We started the conservation project in 2019 November as part of our centenary celebration [inaudible]. Everything was going well, and then all of a sudden, \ the lockdown. And so they could not complete some of the work, some of the project work. And that created a huge, huge problem for the museum.

Now things are pretty under control, keeping monsoon in mind that we could cover most of the museum rooftops with the GI6. cleaning and all that, you know, already been done.

CUNO: How did you first learn of COVID-19? And was the information that you got consistent, or was it contradictory? How did you get your information?

MUKHERJEE: We actually got to know about the disease sometime in January, that it started in China. And towards the end of January, one positive case was detected in Kerala, the southern part of India. To be honest with me, nobody took it seriously. Nobody took it seriously. Life was absolutely normal. We did several programs, exhibitions, events, opening new galleries.

And then the information, you know, we got from the state in the second week of March that, you know, it started in Mumbai. And they requested all institutes to reduce, you know, number of staff and visitors. So we kept the museum closed to the public and reduced number of staff, and started working until 20th March. And then the central government all of a sudden—you know, we had absolutely no idea—there was an announcement and then the lockdown, nationwide lockdown started.

The problem, you know, about transportation and everything, some of our security people got stuck in the campus. We had to make arrangements for their food. They could not, you know, leave the campus for almost two and a half months, and we had to make all arrangements. So it was quite a nightmare. And the building conservation, as I said stopped all of a sudden.

CUNO: Neil?

MACGREGOR: Could I chime in and ask you, you talked about having to repair the roof of the museum. Now, as we all know, Mumbai is a huge city, where everybody depends on public transport, and all public transport stopped at four hours notice. How on earth did you manage to get a work force to come to repair the roof before the monsoon, before the possible cyclone?

MUKHERJEE: It was a painful exercise. We call it, you know, preventive measure. Pre-monsoon preventive measure.

And then the question was, you know, if you want to start preventive measures, then you are expected to accommodate the laborers within the campus. There are families living within the campus. So we waited a little longer. And we were not very confident that the consultant and the contractor can manage. And we found some agency who was willing to come and do the work. And they ensured that, you know, they would look after their staff and they will be doing everything. And they completed the entire work with fifteen days time.

We had to accommodate twelve people, so they camped within the campus. But the agency looked after them. The food and everything, you know, they took the responsibility. We just provided a separate space.

CUNO: So at first, it was a public health issue for you. Did it become a financial issue quickly thereafter?

MUKHERJEE: The finance, you know, yes. You know, the moment we closed, we started working on that. So there were two things. You know, one thing we constituted a taskforce for a business plan. And whatever our, you know, fixed income and how to cut down the expenditure. And then the other team started working on maintenance of collection and the building conservation project.

So what we did immediately, from 1st April, reduction of staff salary. There was a kind of ratio formula. The ground-level staff wouldn’t be affected much. The middle-level and the senior-level staff, 10%, 25%, and 35% reduction.

CUNO: Wow.

MUKHERJEE: And that helped the museum immensely. And then there was another issue: contract staff. We have a little over 100 contract staff. So what to do with the contract staff?

There, you know, we took a decision on humanitarian grounds. The museum will not terminate a single contract staff. And most of the contract staff, they were working on their projects supported by corporate sponsors. So we continued them. And then we decided the next, you know, contract, when their contract gets over, we don’t continue immediately. We’ll be a little selective. Only selected people will be continued on the project.

Today evening, I was busy with the planning and finance committee. We took many decisions, good decisions, to cut down the budgetary deficit. At the same if there is no business for a year, that we’ll sustain, you know, healthy. That measure, that remedial measure was taken.

NEIL MACGREGOR: The decision is a remarkable one, that the staff agreed, all of them, to take a cut so that everybody could remain in the institution. How did you manage that discussion? Was that a discussion, first of all, with senior management? What kind of debate went on inside the museum?

MUKHERJEE: Yes, you’re right, Neil. We had a discussion with the senior management. We also started a kind of dialog with the staff. They were worried about their sustainability. They knew that the museum is not supported by the government. And whatever, you know, management does for them, that will be accepted to them. So when the decision was taken, it was shared with the staff in a very diplomatic manner. And staff accepted it [inaudible]. I don’t remember a single complaint we received from the staff.

MACGREGOR: That’s a very remarkable achievement, I think, in building a community inside the museum. At what stage did this become a matter of discussion with your trustees? You’re unusual, I think, in India, in having trustees, on the British and American model.

MUKHERJEE: We started discussion, I think, in the third week of March. Lockdown started from 21st March. And immediately, we started our discussion. I was constantly in touch with the chairman and the planning and finance committee. And then we shared our concerns with the rest of the trustees. And they all, you know, approved the idea and they said, “Go ahead and do it.”

MACGREGOR: And when this happened, were you caught by surprise? Or did you have any kind of contingency plans already in place for a health emergency?

MUKHERJEE: What we did, you know, thanks to our enlightened trustees and staff, we could create a separate contingency fund a couple of years ago. Never ever thought that we have to face this kind of situation. But that was created for emergency purposes.

The fund can, you know, support at least for a year and a half. And we are hoping against hope the situation improves in the next six to eight months

CUNO: Yeah. Mukherjee, how did you characterize your closing of the museum? Did you just simply say, “until further notice”? Or how did you communicate with the public about the status of the museum?

MUKHERJEE: When we got the notification from the state, being a public institute, you have to, you know, close down as early as possible, we intimated to all our friends, well wishers, agencies, travel agencies, immediately, till further notice. That’s the simplest way, when you don’t know when you intend to reopen

And then after a few weeks, we renewed our relation with our friends. Well, we shared all information with them that what is happening at the museum. Our happiness, our pain, our joy. And many of them got back to us, surprisingly, asking museum management if there is anything, you know, they can do. And that is some part of our business plan, what we are going to implement very soon.

MACGREGOR: And during the period of being closed, how have you been able to keep the staff informed?

MUKHERJEE: We have a list of staff, their mobile numbers and emails. Whenever they want to share any information or any instruction they wish to give the staff, so they sent SMS, mass SMS to everyone, you know, and they receive the information immediately.

So we didn’t have any problem intimating staff about the closure. And then slowly, when government started giving relaxation last month, we started calling our staff, three or four people coming to the museum for maintenance. They do their job and then they leave. For a couple of hours, they come.

MACGREGOR: And how have you been able to keep your different publics engaged with the museum during the time that you’ve been closed?

MUKHERJEE: Largely through social media. Our social media is very, very active. Website. Very few people— You know, they check website, but social media, we could see, you know, large number of people, taking a lot of interest. And then the digital platform, contacting lectures, workshops, demonstrations, music, I think really is extremely vibrant. I think we are probably one of the institutes in the country [that] kept that area alive. And people appreciate it, appreciate it a lot. And that was needed because we wanted to tell our people and our friends that we are here. Though the museum is shut, but we are close to your heart.

MACGREGOR: How do you think this will change the museum’s relationship to its public in the future?

MUKHERJEE: I think the technology in the present situation helped us to build a new relationship with our friends, with our well wishers. They started looking at the institute from a completely different angle. They feel that, you know, time has come. We help, you know, we’ll be around and help the institute. Institute is important. That is what they feel, that the institute should stay.

MACGREGOR: And how do you think this will affect the way that the museum conducts its business in the future?

MUKHERJEE: That’s a good question, because we need to understand the role, you know, in the post-COVID period, what is going to be the role of the museum.

The scenario will change. No question, you know. Many people, they will prefer information through digital technology or social media. But there is another thinking. Most of our friends, largely, you know, young people, they feel the digital technology, the digital cannot replace the museum, the physical space. Art is a physical and cerebral activity that happens in real space and time.

MACGREGOR: How do you rebuild the trust of the public, that the museum is a safe place to come to?

MUKHERJEE: Well, our museum is a people’s museum. It is a public institute, people’s museum. It was created by the people, for the people, of the people. We are not supported by the government. So I’m 100% sure when we reopen, when we share our collection, our stories, stories of people, people will come around. They’ll support the museum. It won’t be much difficult for the management to rebuild, if they develop the way, you know, with sensibility. Sense and sensibility. They are handling the present situation with that same sense and sensibility. If we deal with the future, the post-COVID, it will be much easier for the management, for the staff to rebuild.

MACGREGOR: Have you begun to plan the reopening?

MUKHERJEE: Well, yes. We started. We started a plan, and involved a couple of young people. A group of young people, they’re working on that. And they have already submitted a draft to me, how we reopen the institute step-by-step, and what all measure, preventive measure[s], the institute, the management should take keeping, you know, visitors’ safety in mind.

Most likely within two weeks, we will complete the whole format, the guideline, step-by-step reopening. The only problem we are facing in our country— You know, in Europe and America, even on ground-level staff, they have their own vehicle. But here in India, 85 to 90% staff, they don’t have their own personal vehicle. They depend on public transportation. So that is the major problem. If public transportation system [is] restored, I don’t see much problem. But if that area remains, you know, this thing, then it will be difficult for staff to visit the museum.

CUNO: Mukherjee, we most recently worked together on an exhibition with the British Museum and CSMVS, your museum, on Indian and the World. And this Ancient Worlds Now initiative is developed from that, where we hope to work together with your museum, Mexico City Museum of Anthropology, and the Shanghai Museum, and also the British Museum again, and the Berlin museums, all working together to tell a global story of humanity. What impact do you think the COVID-19 pandemic will have on the way that we work together to share collections and the knowledge in this initiative?

MUKHERJEE: That’s a good question, Jim. The crisis has highlighted socioeconomic inequalities in our contemporary society. And the political situation in the world is also changing with the time. It would be difficult for us to anticipate what will be the situation after six months. As an institute, we are open to ideas. We are learning from the circumstances, how diseases have saved our lives and made us confident to think and work as a global community, to outsmart the pandemic.

CUNO: I was wondering, that part of the underlying story these working relationships will tell, is about the interrelatedness of the world’s culture and the global contacts that were made, even in ancient times. And that is now more poignant, because of the way the pandemic has spread internationally and globally.

MUKHERJEE: That story needs to be told. And we need to share, you know, our story with others. It would be interesting for people to know theglobal story of humanity. We have everything to share. There is nothing to hide.

CUNO: What do you think the long-term legacy of COVID-19 will be on your museum?

MUKHERJEE: Yes, it will leave a mark on the institute, on humanity. But it is also true the history of infections or infectious disease, is also the history of individuals. These are part of our, you know, body. Bacteria, virus, they inhabit us, and we inhabit in the city. But the point, you know, I’m trying to make, it is not the first time. The pandemic we are facing at the moment is not the first time.

Even the plague, you know, in 1896, that was more dangerous than the present COVID. Even the influenza in 1918. Smallpox, 1890, millions of people died. And it took time to overcome.

But the present COVID, yes, we will be losing many lives; there is no question. But there is a hope.

The pandemic is also an opportunity, looking at different issues, because there are many things, you know, we ignored in the past, even the climate. Climate was completely ignored. And today we understand the importance climate, the importance of environment.

A lot of things went wrong with urban planning. The inequality in our society. Now the poor are, they are most vulnerable to this disease. There are areas, you know, the slums, where ten people, fifteen people living in ten feet by ten feet room. So these are the things exposed, exposed by the disease. And these are the things we need to rectify, we need to understand, to face, you know, the future pandemic.

On our museum, the experiences we pass through and we are already passing through, everything we are recording for the future. And we also started collecting some evidences, COVID-related evidences, information in the city and in the country, for the future. Maybe in future, that that information will tell policy makers, urban planners. Many things went wrong with the present planning. And that learning will help the future.

CUNO: Well, thank you very much, Mukherjee, for joining us on this podcast. It’s always great to talk with you, and we wish you the very best and the safest future. And we look forward to working together on the Ancient Worlds Now project, once we emerge from this pandemic. And Neil, as always, thank you.

MUKHERJEE: Thank you. Thank you, Jim.

MACGREGOR: Thank you very much.

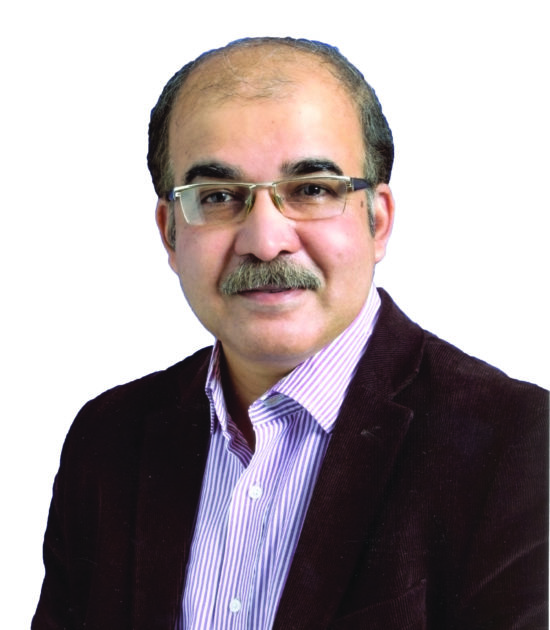

CUNO: Shortly after speaking to Dr. Mukherjee, Neil MacGregor and I spoke with Dr. Antonio Saborit. He is the director of the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, a post he has held since 2013.

Okay, Antonio. Thank you for joining us on this podcast episode. It’s great to be in your company again, if only virtually. Last time we were together was about three months ago, and we were talking then about prospects for the future. And now, of course, the future is clouded with the pandemic and COVID-19. What’s the current state of affairs in your museum and in Mexico City generally?

ANTONIO SABORIT: Well, the museum is closed to the visit, since the middle of March.

CUNO: Just after we left. I mean, we were there in the early part of March.

SABORIT: Yeah. Yeah, yeah. Yeah. But we have been working in the museum in a couple of projects that we had started early on, at the beginning of the year. And we have to move on, because both are very important.

One of them has to do with the pond in the main yard of the museum.

CUNO: A water pond.

SABORIT: Exactly. You would say it’s maintenance, but it’s more than that.

And the other one is the installation of the new equipment for the detection of smoke and prevention of fire in the museum. We’ve been working on this project since a couple of years ago, and we have started in January to install the installation of this equipment. And originally, we thought that we’d have to work by night, because imagine the Museum of Anthropology; it is impossible to close the museum. And now the museum is closed and we are working all the time on both projects. So we are, in a way, very happy with them. And most probably, we’re going to finish early on.

At the same, we’re working on the galleries, cleaning them. The museum is shining. We are working with having on the horizon, that day when the museum will open its doors again.

CUNO: And when did you first learn of COVID-19, and how did you hear about it? And what kind of information did you get? I mean, it must’ve happened very rapidly, because as I said, we were together just a few months ago, and just before you closed the museum.

SABORIT: It’s a very interesting question. One of my favorite books is Daniel Defoe’s memoir of the plague, or the Journal of the Plague Year. I teach this book each semester. It is one of my favorites. And I think this helped. It gave me some sensibility to the news that I read in the newspaper, what was going on in Wuhan.

And I said to myself, “Oh, my God, this is coming. The wave is coming toward us sooner or later.” And in February, I was really worried about what I read in the newspapers. So we bought this gel for the visitors, for their hands.

CUNO: For hands, washing, yeah.

SABORIT: And having in 2009 the experience of H1N1 pandemic in Mexico. And in fact, in Mexico City, everything was closed for a couple of weeks.

This concern grew rapidly among my colleagues in all the museums. I think that those of us that work in these places where so many people gather daily were really worried about the health of the people in general.

So when the Mexican government, particularly the Ministry of Education, announced that— the end of classes two weeks before the break of holy week, I was really happy. It was a very clear announcement that finally, here, something was happening towards this threat.

Immediately, our visitors understood what was going on.

CUNO: How did you your closing to the public?

SABORIT: It was a public announcement, not made by the museum, but by the Ministry of Health, saying that museums and schools and offices were closed.

CUNO: Did it quickly become a financial issue for you, or was that— are you secure from that because of your government funding?

SABORIT: Yeah, it’s very strange. It’s a very interesting paradox that normally, the public museums are always on dire straits in their financial life. And in this— in this process, at least right now, it seems that the public museums are better— I wouldn’t say prepared, but they are in better condition than private museums that depend directly on the visitors and all the services that those museums offer.

We knew that the budget will drop, but it is not exactly how I would like to phrase it. Because if you close the museum, of course, your expenses go down.

Well, I knew immediately that this was going to be a very long suspension of activities in our museum. And in our society in general.

The National Museum of Anthropology belongs to the National Institute of Anthropology and History. And we were sure that security, maintenance, and cleaning would still be working during all the year. We have the funding for these three very important aspects. And in a way, I was relaxed, so to speak, releived.

MACGREGOR: Yes. Antonio, you’re a state museum. So you don’t have trustees, in the British or the American sense. What kind of structure do you have for governors to make these decisions and to discuss these things?

SABORIT: Let me tell you about our trustees. It is not exactly trustees in the American or Anglo-Saxon understanding of the term. It’s more like a society of friends, friends of the museum or something like that. People that gather in order to get funds for the museum. And in fact, these two important projects that I mentioned at the beginning of our conversation, we owe them to them.

MACGREGOR: Yes. Did you have any contingency plans in place for an emergency of some sort, of this kind of dimension?

SABORIT: No. No, no. We are living a very unusual situation, I think for everybody. It’s brand new. Well, I would assume that for everybody, not in Mexico but everywhere, it’s— this is brand new, and we are dealing with a— with a variety of optimisms all around us, no?

Someone said that we will be back to normal in two months, in two weeks, in four. I’m a historian, remember. And I said to my friends in Zoom, “Well, let’s do some rehearsal of our Christmas dinner now, in order to get it fit for December, because in December, we will be where we are.”

MACGREGOR: I think we all like the idea of living with a variety of optimisms.

How do you keep your senior management engaged to decide what happens next and when things happen?

SABORIT: We are meeting frequently. I would say two times per week, so to speak, reviewing everything, sharing reflections and facts. And in a way, looking carefully all around, in order to have a better evaluation of what’s going on.

And well, time runs very slowly in this situation. And when someone says to me that in a month, I say, “Well, a month, it’s like an age for me.” We are working day by day, you know? Day by day.

And the museum helps me to keep my head clear. My focus is on these two projects and in the good state of our galleries. Trying to have them ready for that day, for the opening day.

CUNO: Antonio, how did you announce your closing? How did you inform the people? And how clear were you about when you are going to reopen?

SABORIT: To the public, as I mentioned before, it was an announcement from the top, from the Ministry of Health. Or in fact, it was an order to close all the public offices, including museums, archaeological sites, schools, and all that.

They have been working on several horizons of optimism. They said first— Maybe it’s the way— I don’t know, I’m very ignorant in this respect. Maybe it’s the way to handle a situation like this, using different words to create different scenarios for the people. Maybe not everybody is prepared to face, emotionally or intellectually, a closure of eight months. So it’s important to give the people the idea that this will be short. No?

At the beginning, it was April, middle of April. Pretty soon, till the end of May. And in May, the government prepared a set of standards, in order to return to normality.

Since the very beginning, there was a minimum protocol about washing hands and all that. And we have been working inside the museum and inside the institute, the National Institute of Anthropology and History, in protocols for the opening of our museums, when this happened.

We have been working with several— with biologists, with people involved in restoration and all that. And the idea is to get a very precise protocol for that epoch. But in my view, it will take us some time to get there.

MACGREGOR: Antonio, you— I take it from what you’re saying that you haven’t had to lose any staff, because the government is continuing to pay them. Is that right?

SABORIT: Yeah, yeah, yeah. In fact, we are working harder than ever. I mean— We are slaves of the Zoom.

CUNO: Yes, we all are.

MACGREGOR: We all are.

SABORIT: It is fantastic, in a way, let me tell you. Inside the institute, there is an office that coordinates the work in all the museums of the institute. And now we have three meetings per week. It is fantastic to be in these meetings. Because I know about their conditions in all the country, their hopes, their ideas about their museums, and how we can help, you know, each other.

MACGREGOR: So you’re closer to your other colleagues in the museums across Mexico than you were before.

SABORIT: Yes, exactly. Let me tell you this. More than a year, almost two years ago, we began to meet in a sort of seminar, with curators of the ethnographic section of the National Museum of Anthropology. We want to change what we have. But radically. And as you know, everything is very slow in a museum.

Now we have one meeting per week. And we are working faster than before. We are very enthusiastic. It’s really fantastic. So in a way, we are closer, yes. Yes.

MACGREGOR: What you’re saying, Antonio, makes the point that your museum, the National Museum of Anthropology, is one of the great symbols of Mexico. How have you been keeping the Mexican public, your publics, informed of what’s going on and what you’re planning for the future?

SABORIT: We keep alive our Twitter account and our Facebook account to communicate what we do. We have a YouTube channel and through this channel, we show a lot of the material that we have. In our web page, you can get a virtual access to the galleries of the museum. It will never replace the physical visit to the museum. But at least, that’s what we have right now.

MACGREGOR: Do you think it will change your future relationship with your public?

SABORIT: Yeah. I think we’ve got to think in new tools to better our link with our public.

When I was invited to be the director of the National Museum of Anthropology in 2013, I received the museum with 1 million visitors per year, more or less. We were heading toward our fiftieth anniversary, 2014, and we began slowly to upgrade this number, till this year, when we received in the first three months of the year, 900,000 visitors, just before we closed.

But we were deeply concerned about the quality of this visit. We had been working on how to enhance the quality of the visit. Not just a walk in the museum, but to offer more to them.

I think that we have to create new tools for everybody. We were, right then, thinking in tools for the teachers. A sort of handbook, how to use and exploit and understand what we have in the museum. And in this way, help these teachers to give to their kids more information, more accurate information, and up to date to them.

At the same time, I have been working hard on enhancing the museum, the site of the museum as a— as an archive, as a fantastic place for do[ing] research.

MACGREGOR: And how do you persuade the public that this will be a safe place to visit when you do reopen?

SABORIT: Yeah, that’s a fantastic question, Neil. Let me tell you this anecdote. After the earthquake in 2017, I was flying from L.A. to Mexico City. The earthquake happened when I was flying. It was— it was a nightmare for me.

I finally arrive at the museum in the night, at ten. I was almost all by myself, with a security team. And nothing happened in the museum. Immediately, that same day, our teams began to check everything inside the museum. By the end of the day, we knew that the building was alright. Next day, Wednesday, all the teams began to work to collect those objects that fell. We had minor, really minor casualties inside. Seventeen pieces or something like that. Nothing to worry about.

And the government gave the order to close everything. Everything. We had several reviews by several teams—from the government of Mexico City, from the federal government, from our own institute. And finally, we invited our— the doctor of the house, an engineer, fantastic engineer that helped us with these things. And he went in on a Saturday. Almost two weeks later. And we walk all the museum. And finally he says, “The museum is safe and sound.” By then, we opened.

And we had an academic activity that afternoon, at our main auditorium. Well, at five o’clock, the auditorium was packed. Packed. Full. People standing there. Almost 400 people.

And I told to the public, “Welcome to the museum. I’m here, supposedly, to tell you who these two guys are, but I have to tell you thank you very much, to be here in the museum. This morning we have the last of several reviews of our building, and the National Museum of Anthropology is safe and sound.” And everybody clapped. No? Almost a standing ovation, you know?

Then I told them, “But you didn’t know that, and you still came here. Thank you for your trust.” And then I get another big applause. So the people trust in the museum. It’s like a cornerstone, no? It cannot fail. The National Museum, it cannot fail.

MACGREGOR: It’s a marvelous position to be in.

SABORIT: Yes, exactly. But at the same time, it’s a big, a huge responsibility.

MACGREGOR: It is. What do you think will be the impact of the COVID-19 on your international work? The National Museum of Anthropology is a major international player. What impact will this have on that role?

SABORIT: Well, I think that in a couple of years, we will be back to normal. I’m sure of this. So let’s make the most of all these reflections, considerations that we are having these days. Because these ideas are very important for the future of our museum. And it’s important not to forget them. Because I’m sure that as soon as we get back to normal, all these fantastic initiatives, ideas, plans will fade under the wave of normality. You know, we tend to forget very easily.

CUNO: Antonio, last time we were together, we were talking about Ancient Worlds Now. And of course, the story then was about the global history of humanity and the interrelatedness of our cultures. And one aspect of that must now be the spread of pandemics. This is the way we will be working together with the Mumbai Museum and the Shanghai Museum and the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, together with the British Museum and the Berlin museums, to tell these global stories of humanity.

What do you think about the story that might be told with COVID-19 now, as part of the initiative that we’re talking about, the Ancient Worlds Now?

SABORIT: I think that it’s important to share among us how we are living, how we are experiencing this, and how we are organizing our thoughts in these times. How are we thinking, if we are thinking at all, of our place in this Earth? And above all, about the place that we occupy in this scenario. We are in the world of these fantastic institutions that are called museums. What do we have to offer for our time, for our society?

I think it’s not only a certain sadness for the impossibility that we face now, to offer huge exhibitions or to host crowds for these exhibitions in our museums now.

At the same time, how is it that we are going to tell these stories that we share as humans, around a threat like this? You know? We need to talk a lot, to read a lot, to write, to— There’s a lot of work for us. Let’s work together.

CUNO: It is a project.

SABORIT: Yeah. But to where? We do agree on something essential. Let’s work together.

CUNO: Let’s work together.

Well, Antonio, we’re thrilled by your optimism, buoyed about your optimism about the future of not only this globe, but also the project that we’re talking about. So I want to thank you for giving us so much of your time this morning. And Neil, I know I will always want to thank you for being part of our project.

SABORIT: Thank you , James. Thank you, Neil.

MACGREGOR: Thank you.

CUNO: This episode was produced by Zoe Goldman, with audio production by Gideon Brower and mixing by Mike Dodge Weiskopf. Our theme music comes from the “The Dharma at Big Sur” composed by John Adams, for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003, and is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday, subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and other podcast platforms. For photos, transcripts and more resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts/ or if you have a question, or an idea for an upcoming episode, write to us at podcasts@getty.edu. Thanks for listening.

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, President of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

ANTONIO SABORIT: Let’s make the most of all these reflections, considerations that we are having...

Music Credits

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.