Subscribe to Art + Ideas:

“One of the hopes of this exhibition was really to try to enlist visitors’ bodily experience in their understanding of these works of art that can sometimes seem a little bit like they live entirely in our heads, a little bit intellectualized.”

Although Nicolas Poussin is widely regarded as the most influential painter of the 17th century—the father of French classicism—he is not as well-known as many of his contemporaries, such as Rembrandt, Rubens, and Caravaggio. This is due, in part, to Poussin’s austere painting style and erudite subject matter, which often came from Roman history or the Bible. As a result, his work can sometimes feel a bit cold or remote to today’s audiences.

But earlier in his career, Poussin was inspired by dance. His paintings of wild revelry, filled with dancing satyrs and nymphs, emerged as his signature genre from that time. Poussin and the Dance, organized by the Getty Museum and the National Gallery in London, is the first exhibition to explore the theme of dance in Poussin’s work. By supplementing his delightful dancing pictures with new dance films by Los Angeles-based choreographers—this unique exhibition invites viewers into the world of Poussin in a fresh, relatable way.

In this episode, Emily Beeny, curator in charge of European paintings at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and curator of Poussin and the Dance, joins Sarah Cooper, public programs specialist at the Getty, to delve into Poussin’s process and love of dance.

The exhibition, which received generous support from the Leonetti/O’Connell Family Foundation and is sponsored by City National Bank, is on view at the Getty Center through May 8, 2022.

More to explore:

Poussin and the Dance explore the exhibition

Poussin and the Dance: Contemporary Dance Films watch the dance films

Poussin and the Dance buy the book

Transcript

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

EMILY BEENY: One of the hopes of this exhibition was really to try to enlist visitors’ bodily experience in their understanding of these works of art that can sometimes seem a little bit like they live entirely in our heads, a little bit intellectualized.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with curator Emily Beeny and public programs specialist Sarah Cooper about the Getty exhibition Poussin and the Dance.

Nicolas Poussin is widely regarded as the most influential French painter of the 17th century. In the 1630s he was recalled to Paris from Rome to serve as Louis XIII’s First Painter. A decade later he returned to Rome, where he spent the rest of his life.

In the 1630s Poussin brought lessons learned from dance to bear on every aspect of his work. The exhibition, Poussin and the Dance, organized by the Getty Museum and the National Gallery in London, is the first exhibition to explore the theme of dance in Poussin’s work.

I recently spoke with Emily Beeny, curator in charge of European paintings at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, who curated the Getty presentation of Poussin and the Dance, and Sarah Cooper, public programs specialist at the Getty, who co-curated the newly commissioned dance performances that accompany this exhibition.

Our conversation took place in the exhibition galleries.

CUNO: Emily, Sarah, thank you so much for speaking with me today on this podcast episode. Emily, tell us about the origin of the exhibition, Poussin and the Dance.

BEENY: Well, the exhibition really began with my dissertation research. I wrote a dissertation about Poussin’s work in the context of 17th century French, from the standpoint of patronage and iconography and theories of bodily expression. But from the beginning, I sort of imagined this research would eventually take the shape of an exhibition. I hoped, I dreamed. And I knew that the National Gallery in London would be the ideal partner, because their collection contains really the greatest of the dancing pictures.

CUNO: Now, we say Poussin is the most influential painter of the 17th century. And yet I’d venture to guess that he’s much less known to our museum-going visitors than, say, his Dutch, Belgian, and Italian contemporaries—Rembrandt, Rubens, and perhaps Caravaggio. Why is that? Why is he so little known, compared to them?

BEENY: He is definitely much less well known than figures like, yeah, Rembrandt, Caravaggio. My goodness. I think that has something to do with the kind of drama, immediacy, naturalism of artists like Caravaggio and Rembrandt. I think there’s a way in which Poussin sometimes holds us a little bit more at arm’s length.

The slightly austere Classicism, especially of his later work, and the extremely erudite and carefully-worked-out subject matter, coming from Roman history or the Bible or Classical literature, can I think, sometimes feel a little bit forbidding to general audiences. But you know, Poussin has really always been an artist’s artist, revered by subsequent artists from Charles Le Brun down to Cézanne, down to Picasso. And so I think, of course, he has something to say to us today, since so many artists continue to be so interested in his work.

CUNO: Although Poussin was French, he principally painted in Rome. Why was that?

BEENY: Well, I think it’s important to remember that Rome in the 1620s, you know, at the time when Poussin arrives, is really— It’s Paris in the 1890s; it’s New York in the 1950’s; it’s sort of Los Angeles today. It’s the beating heart of an international art scene. It was really sort of attracted, in that case, by the patronage of the papal court; but also by the incredible artistic riches that existed in the Eternal City.

So Classical antiquities, of course, treasures of Italian Renaissance painting, and also an international community that existed there, including many artists from Northern Europe, as well as, an important population of Italian artists. So I think that was really what drew Poussin to Rome.

CUNO: Now, in the late 1630s, he was recalled to Paris to serve as the first painter to the king, Louis XIII. But he remained just a few years in Paris. Why did he give up that, what I have to assume to be a plum position?

BEENY: Well, Poussin took some persuading to go back to Paris in the first place. Obviously, yes, the position of premier peintre to the king was coveted. But he was actually sort of initially invited several years before he left. And in fact, we have some evidence that some of the agents of the king who approached him in Rome may have, in the end, brandished some threats.

CUNO: Physical threats?

BEENY: Yes, so one agent, of Richelieu— of the first minister, is said to have been instructed to remind Poussin that he is a French subject and that kings have long arms. So it’s possible that he comes back to Paris somewhat reluctantly to begin with. And I think that he finds the job that awaits him there really ill-suited to his talents.

It’s basically a managerial position. He’s supposed to operate an enormous workshop that will decorate the Grande Galerie of the Louvre, a huge campaign of decorative painting that will turn out gigantic altarpiece after gigantic altarpiece. And he’s also expected to navigate the complicated political landscape of the French court.

On top of all of this, all of these sort of unaccustomed managerial tasks for an artist who isn’t accustomed to working with a very large team, he is deprived of the pleasures of life in Rome—day-to-day contact with Classical antiquity, opportunities to study the work of Raphael. I think it’s important to remember that Paris in 1640 is not a very pleasant place to live. You know, it’s a bit of a city of frozen mud.

And it’s quite telling, I think that Poussin doesn’t relocate his wife, Anne-Marie, when he comes to Paris. And his pretext for leaving is that he’s going to go and retrieve her from Rome and return to Paris; but of course, then he never does. And then Richelieu dies and then Louis XIII dies, and then nobody is banging down his door to come back to Paris.

CUNO: Who were his principal patrons, and I assume they lived principally in Rome, these patrons?

BEENY: So this is quite interesting. When he first arrives in Italy, certainly, Cassiano dal Pozzo is his most important patron, and in many ways, remains his most important patron-slash-intellectual interlocutor.

CUNO: Tell us about him.

BEENY: So Cassiano dal Pozzo, he’s a learned antiquarian, a natural scientist. He’s a correspondent of Galileo, as well as many other intellectual sort of luminaries of the 17th century. But he’s really best remembered for amassing what’s called the Museo Cartaceo, the Paper Museum, which was a kind of collection of over 10,000 prints and drawings that comprised a kind of visual encyclopedia, basically, of Classical antiquity.

It contained a lot of images after antique fragments, antique statues, surviving oil lamps and tripods and things like this; but also after botanical specimens, zoological specimens, geological specimens. It really was a kind of visual encyclopedia of the period, an extraordinary sort of achievement.

And Poussin contributed to the Paper Museum; he made drawings for it. But also, as a friend of Cassiano and recipient of his patronage, he had access to it as a resource to consult in creating his own compositions, his own imaginings of Classical antiquity. So Cassiano dal Pozzo remains a really important patron for Poussin right up until Cassiano’s death in 1657. But I would say that in the second half of Poussin’s career, after his time in Paris, two of his most important patrons are French. And he does have sort of a community of French collectors who are very interested in his work during the second half of his career.

Foremost among them are Paul Fréart de Chantelou, for whom he paints his second set of the Seven Sacraments and many other wonderful pictures; and Jean Pointel, a Lyonnaise silk merchant, a very wealthy guy, who’s a patron of most of Poussin’s great landscapes in the second half of his career, a luxury that few 17th century artists enjoyed. Which is to say that he could paint almost whatever he wanted, almost however he wanted, and they would just buy it. I mean, nobody gets to do that.

CUNO: How did he live in Rome? Under what circumstances did he live?

BEENY: His first years in Rome are pretty hardscrabble. We know that he has a series of different roommates, perhaps most important among them the Flemish sculptor François Duquesnoy, who’s a close friend. They spend a lot of time sort of crawling over the ruins and remnants of ancient Rome together, measuring statues, making sketches.

We also know that they copy after Titian’s Bacchanals together, both in oil paint and in clay, which Duquesnoy seems to have taught Poussin how to model. But those early years seem to be quite hardscrabble. He also apparently contracted the mal francese, syphilis, in those early years, and almost died of it. Around 1629, his illness seems to have reached a kind of crisis point, and he survived only thanks to the help and care that he receives from his neighbor, a fellow French expatriate called Jacques Dughet.

And Poussin actually ends up marrying Dughet’s daughter, Anne-Marie Dughet, in the fall of 1630. And the dowry that comes along with her in their marriage allows Poussin to kind of settle down. It allows him to purchase a lifetime lease on a little house on the Via Paolina that I think underwrites the kind of stability of his career and his life thereafter.

And I think that one of the ways in which this shows up in his work is that it’s around the same moment that he switches to using more expensive colors. So the work from the 1620s is often painted with inexpensive earth colors that have grown transparent over time, leading to a kind of darkened appearance in his pictures; that we’re actually sort of seeing through the thin layers of inexpensive paint to the red ground that he used to prepare his canvases.

But after around 1630 to ’31, he’s using more paint and more expensive colors, more lead white. And so we get these kind of somewhat sturdier paintings. I feel like The Realm of Flora is a perfect example of this.

CUNO: Emily, you say that Poussin is remembered today as the father of French Classicism, “a serious painter—more revered perhaps than loved—” you said in the catalog, “known for learning and stoic self-restraint.” Why was that, and what are the stylistic and iconographic characters of his work?

BEENY: Well, Poussin is an artist whose style changes a lot over the course of his career. The early material, with its sort of debt to Titian and its embrace of wild Bacchanalian iconography, is a really pretty different kettle of fish from the later work, which does tend to be very much more serious, both in its subject matter and in its really sober, very carefully-thought-out approach to composition—the disposition of bodies in space, geometric setting of architecture, and so on.

I think we have, you know, in a sense, a kind of growing seriousness over the course of Poussin’s career. And in terms of the kind of label of stoic or stoicism that’s sometimes associated with his work, this has to do with his choice of subject in the second half of his career—this interest that he describes in a famous letter to Chantelou, to one of his French patrons, in portraying the tricks of fortune, the terrible things that can befall people in the course of human life—partly in order to encourage people to endure, to encourage a kind of forbearance.

You know, there is, I think, a desire, especially increasingly in the second half of his career, to use painting as some kind of mode of moral instruction.

CUNO: Well, you and your curatorial colleague Francesca Whitlum-Cooper, curator at the National Gallery London, have focused in this exhibition on Poussin and the dance. How does that tell us more about Poussin?

BEENY: Well, you know, I think even in the early stages of the dissertation, I was imagining that this group of dancing pictures would make a wonderful exhibition. And I think Francesca really agreed that this could be a more inviting way into the world of Poussin, an artist who we sometimes do think of as rather difficult or austere or remote, an artist whose work maybe doesn’t seem like it’s for everyone. But we’ve all danced at a cousin’s wedding, or maybe taken ballet lessons or had some lived experience of dance.

So one of the hopes of this exhibition, I think for both of us, was really to try to enlist visitors’ bodily experience in their understanding of these works of art that can sometimes seem a little bit like they live entirely in our heads, a little bit intellectualized. A way of trying to get visitors to think about their own experiences of dance, in looking at these works.

CUNO: Well, let’s get to the dance. Tell us about this painting, The Realm of Flora, from Dresden, 1630-1631.

BEENY: Oh, my goodness. This is such a beautiful painting.

CUNO: First of all, it’s radiant with golden light.

BEENY: Yes, yes. So we’re just thrilled to be able to really begin the exhibition with this work. It’s one of the few works from Poussin’s early career that can be dated with some precision. That’s because it actually served as evidence in the criminal trial of its original owner, who was this sort of shady character, a Sicilian gentleman-crook, who was arrested in the summer of 1631 for laundering stolen diamonds through the Roman art market.

He had purchased or commissioned works from a number of sort of leading contemporary artists in Rome, and this was among them. And so we know from the proceedings of the trial that it was delivered in early 1631. Poussin actually testified at the trial, which how we know that he was not paid for this painting in diamonds. He referred to it as un giardino di fiori, a garden of flowers. But its subject is actually, a fairly precise mythological subject. Though as so often with Poussin, there’s been some scholarly debate about the exact literary source.

In any case, it represents characters from Ovid’s first century mythological poems, The Metamorphoses and the Fasti. Notably, Flora, Roman goddess of gardens and spring. She’s dancing right at the heart of the composition, surrounded, or sort of behind her, is this little ring of chubby putti, who are dancing in a circle behind her.

And then she’s surrounded by this human garden, characters from The Metamorphoses, from the Fasti, who are mortals transformed in death into flowers of different kinds. Moving across the canvas from left to right, we see Ajax, the mad warrior who commits suicide, falling on the sword of Achilles. And there’s a carnation actually bursting into bloom from the hilt of the sword.

Next to him, we see, kneeling and gazing at his own reflection in this vase of clear water, is the vain youth Narcissus, who of course, gives his name to narcissism, who will drown because he’s so besotted with his own reflection. But blooming at his knee is this bouquet of narcissus blossoms.

Behind Narcissus is Clytie, who is a mortal who falls in love with the sun god Apollo. We can see that she’s sort of shading her eyes from the chariot of Apollo. He rides through the heavens above, surrounded by the wheel of the zodiac in his, golden chariot. But next to Clytie is a basket of sunflowers. This is sort of an interesting touch. More common for the representation of Clytie would’ve been to represent her with heliotrope. Instead, we have the New World plant of sunflowers, with which Poussin may have been familiarized through the Paper Museum of Cassiano dal Pozzo, through its botanical contents.

And on the right hand of the composition, there’s Hyacinth, the youth who falls in love with Apollo and is wounded when playing discus with the god. We can see that his head is bleeding these blue flowers; those are meant to be anemone flowers. And then next to him is Adonis, the hunter and lover of Venus, who ends up gored by a bull. And you can see that he has this wound in his thigh that, again, flowers are falling from it.

I love the dogs next to Adonis, these wonderful hunting dogs. And then in the foreground, right in front of Adonis, we have Crocus and Smilax. She is wrapping him in this garland of bindweed or morning glory-type flowers. And then Crocus, of course, wears a crown of crocus blossom. But what I love— I mean, there are many things to love about this painting. It is exquisitely preserved.

We can see lots of different modes of handling. These little bright licks of color that describe the petals scattered by Flora, or the ridge of the ribbon that encircles her and that seems to sort of float on the breeze created by her dance. And then there are these extraordinarily free areas, much looser brushwork, as in the kind of golden drapery over the lap of Smilax; or this wonderful flowering trellis that encircles the scene, parts of which almost look like an Impressionist painting, the handling is so cursory and free. It’s really just a magical thing to have in the gallery.

CUNO: Well, let’s walk over to see The Adoration of the Golden Calf, another extraordinary painting by Poussin.

BEENY: So this painting is the only one of the dancing pictures with a subject taken from the Bible. It portrays a scene from the Book of Exodus, this moment when the Israelites, who’ve been wandering in the desert, feel sort of abandoned by their leader Moses, who has gone off Mount Sinai to commune with God, to receive the Ten Commandments. And in his absence, they decide to fashion an idol for them to worship. So they melt down their jewelry, they forge this golden calf. And Poussin figures the worship, the idolatrous worship of this golden idol, as a dance.

We have this joyous round or ring or chain of dancers in the left foreground of the composition, that really looks very much kind of like a Bacchanalian dance going on, at the foot of this sculpture that interestingly, represents not really a golden calf, but a golden bull. And this may have had something to do with the patron of this picture, Amadeo dal Pozzo, who was a cousin of Cassiano’s.

The golden bull suggests that Poussin is thinking about these sort of syncretist conversations having to do with the origins of various world religions, whether Greco-Roman religion, Egyptian religion, and Judeo-Christian religion, that are going on in the circle of Cassiano dal Pozzo, in the antiquarian circle in Rome.

I think it’s an interesting possibility that this bull god, in Poussin’s mind, represents the Egyptian bull god Apis, or you know, Serapis, and that this is a sort of practice of idolatrous worship that the Israelites have, in fact, imported from their time as slaves in Egypt. I love, too, in this painting that Moses, we see him coming down the mountain with the tablets of the Ten Commandments in hand at upper left; but he’s this sort of tiny, barely visible figure. He’s totally upstaged by the calf, by the dancing.

CUNO: What about this drawing, which is such a famous drawing, Dance to the Music of Time, of 1634?

BEENY: So this drawing prepares really the most famous of the dancing pictures, which hangs today in the Wallace Collection in London. And Francesca Whitlum-Cooper and myself were so just delighted that that painting was able to cross London, for the first time in well over a hundred years, to appear at the London presentation of our exhibition. So that painting has not traveled to Los Angeles, but we’re thrilled to have this beautiful drawing from Edinburgh in the exhibition.

The subject is a dance to the music of time. And it’s really a kind of allegory of human life, represented by these four figures dancing in a round, to the music of Father Time, who’s pictured, this old man with wings, playing a lyre on the right-hand side of the composition, while overhead, once again, Apollo the sun god rides his chariot through the heavens.

The four figures, representing the different sort of conditions of human life, correspond to poverty, with her back turned to us, her face is kind of in shadow; labor, who’s on the far right of the round, has this very sort of muscular shoulders, this slightly turbulent pose; beside her, wealth, in the foreground, who looks a bit more serene; and then at far left, pleasure, sort of kicking up her heels, unaware of the fact that she’s skipping off towards poverty.

I think, you know, it’s a subject that was set for Poussin by the patron of the picture, Giulio Rospigliosi, later Pope Clement IX. And he was, among other things, the author of libretti for operas that were performed at the Barberini court in the 1630s and 1640s. And the iconography here overlaps in important ways with the iconography of some of those entertainments, especially the danced intermezzi, the sort of balletic interludes in those performances.

But really, it offers a rather profound meditation, I think, on the changeable fortunes in human life and the cycles of joy and suffering that we experience over the course of time. It’s a magnificent drawing. You know, in comparison with the painting, which has this real feeling of stillness, the drawing has this amazing sense of dynamism, fluidity, motion.

CUNO: Now, Poussin returned repeatedly to the motif of a chain of dancers, as you’ve just described in this drawing, as in the painting Hymenaeus Disguised, 1634-38. Tell us about this painting.

BEENY: Yeah. For sure. So this is easily the largest of the dancing pictures, more than 12 feet wide, and the opportunity to see it in this exhibition is really quite extraordinary. It was acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts in São Paulo Brazil in the 1950s, and really has not left that institution since. So we’re enormously grateful to our colleagues in MASP [Museu de Arte de Sao Paulo] for making this exceptional loan.

So the subject of this picture comes from Servius, a fourth century grammarian, from his commentaries on The Aeneid. However, we think that Poussin knew about this story not from Servius, but from the Imaginis of Vincenzo Cartari, a sort of emblem book, a publication used by a lot of early modern artists, as a point of reference and a source for imagery of the antique.

So at far right, we see this slightly taller lady than all the other ladies in the painting. The only person wearing sandals, the only person who doesn’t know that he should take off these sandals when he’s standing on sacred ground, for we are attending a sacred fertility rite in this painting. So that sort of suspiciously tall figure is actually a man in disguise, the Athenian youth Hymenaeus, who later becomes the god of marriage, Hymen. And so he is disguised here as a woman, in order to observe this secret fertility ritual, in which his beloved is a participant. She’s an aristocratic Athenian lady, you know, somebody high above his station. But there’s a sense in which this object is kind of pretextual. Really, this is a grand decoration, with this beautiful braid of interlacing figures, these dancers, these musicians arrayed in front of this elaborate topiary architecture, with the garlands of flowers kind of distributed everywhere across the scene.

It’s a magnificent thing, just in terms of its design, in terms of its dynamism, in terms of its scale. And the enormous scale really has to do with the commission for which it was produced, which was for the Buen Retiro Palace of Philip IV of Spain, this pleasure palace built in the 1630s on the outskirts of Madrid and filled very quickly with a huge number of paintings, 800 pictures in all, purchased to decorate it.

CUNO: Sarah, you had some thoughts about this painting.

SARAH COOPER: One of the choreographers that we engaged for the dance films looked at this picture in particular. And that’s Ana Maria Alvarez. And what she creates in her film almost is a similar scene, a private ritual being performed by women, and we are sort of the onlookers into these moments that are shared by a group of women dancing amongst the landscape. They’re all wearing these really rich, earth-toned fabrics, moving throughout the wind.

And they’re all sort of moving very unselfconsciously, so you feel like there is this mystery of ritual happening in her scene. It’s just one of the many aspects from Poussin that Ana Maria manages to blend into her film. But also, what comes to the fore at the end of her film is all the women join hands and form a ring. And that’s the theme that we see in this section of paintings, and particularly here, with the braided handholding amongst these dancers. That reference was something that Ana Maria really found resonance with, and recognized it as a form in Latin dance. And that connected to her own background, as this sort of common, uniting form of dance.

CUNO: Emily, this is the place in the exhibition where we’re confronted by these carved marble objects of large vase-like form over here and a relief on the wall over there. Tell us about these and what role these played in the career of Poussin, or in stimulating a work by Poussin.

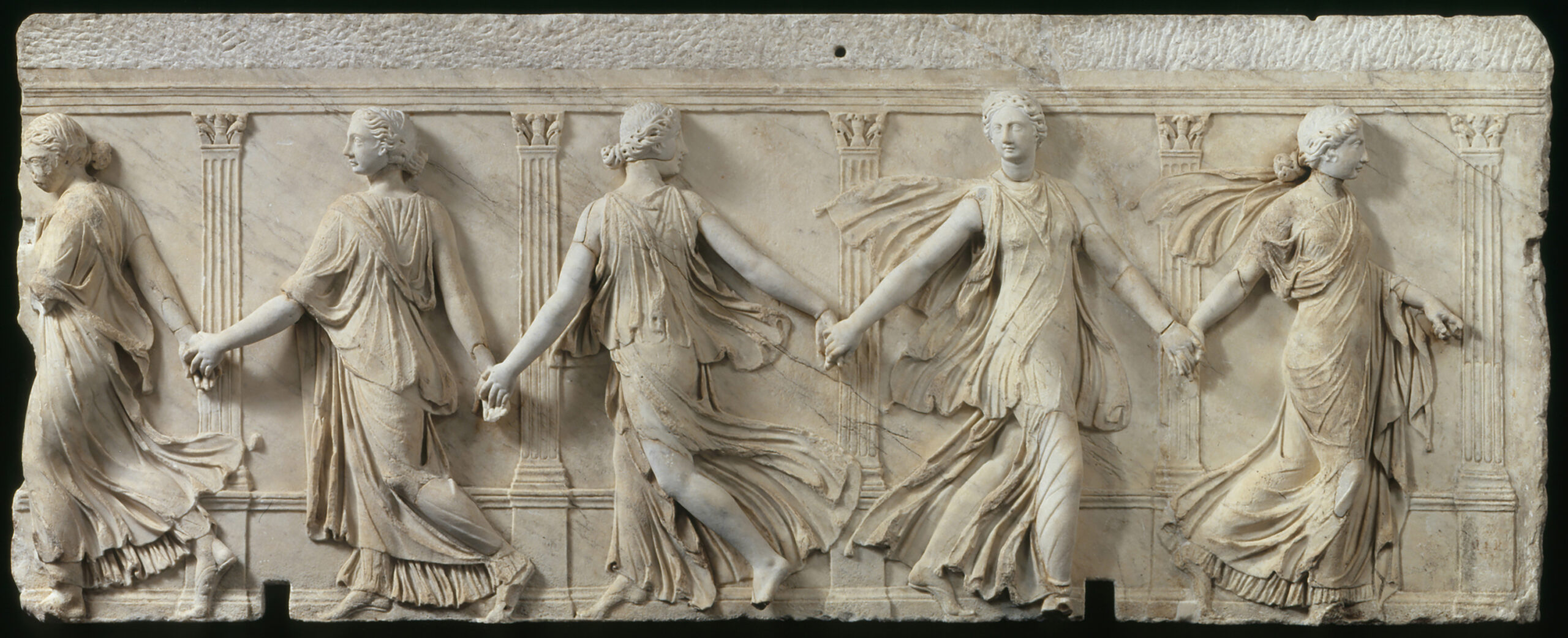

BEENY: Well, we’re very fortunate to be able to display two of the antiquities where Poussin really found this theme of dance frozen in time. I think the reason he begins to paint his own scenes of dance and dancers is that he admires the way that these antique dances are captured in relief sculpture surviving from Greece, from Rome. So this example is The Borghese Dancers, which we think dates from the second century.

It’s a Roman work. And it portrays five figures interspersed with these sort of fluted columns. So they’re in a kind of rhythmic procession of bodies, each one’s garment slightly different. But their clothing seems to flutter in this breeze, suggesting the way in which they’re moving. I should also maybe point out that the heads are not original in this sculpture, but they are the heads that Poussin would have seen on these figures. They were probably assigned to them by an early modern restorer before Poussin’s time.

In Poussin’s time, this work would’ve been on view as an over-door decoration at the Villa Borghese, which is where he would’ve gone to study it, no doubt to draw, perhaps even to clamber up somehow and measure the proportions of the figures. And this sort of rhythmic pattern of figures with arms outstretched, with fluttering garment, it finds echoes everywhere in the dancing pictures.

CUNO: What about the great big vase? It comes to us from the Louvre.

BEENY: This is such a magnificent object, and I’m just so honored and delighted that we’re able to present it in the galleries. I think Poussin would have been thrilled if he could have known that his own paintings would one day hang opposite this magnificent sculpture.

It’s a monumental object. Sitting on its pedestal, it’s certainly taller than I am. It’s a krater-shaped vessel, produced really as a garden decoration in the first century BCE in Greece, but for export to Rome. It was unearthed in modern Rome, in the 16th century, and quickly became really one of the very most celebrated antiquities in the Eternal City because of the extraordinary refinement of its carving.

The frieze that wraps around the vessel portrays Bacchus and Ariadne, but also a series of vignettes of Bacchanalian revelry. So figures dancing and kicking up their heels, slumped in drunken stupor. There’s a darling little panther sort of gnawing on a thyrsus. There’s a discarded wine cup. It’s just such a magnificently beautiful object. And really, the more you look, the more details you find. And I think in the context of the exhibition, the more we go back and forth between Poussin’s pictures and this beautiful krater, the more we see that he lifted individual motifs for so many of his paintings from this specific object.

CUNO: It’s so interesting, I think, that the dance can serve multiple cultural purposes—metaphorical, historical, Biblical, mythological. But it isn’t kept within one frame of reference.

BEENY: Yeah. You know, thinking about the different ways in which Poussin uses dance in his pictures, for me, to consider the fact that the Bacchanalian Revel before a Term, displayed on this wall over here, a wonderful picture from the National Gallery, and The Adoration of the Golden Calf, those two pictures recycle the same choreography.

So the configuration of dancers is identical in those two pictures, but simply flipped. And the subjects of those two paintings are very different. The Bacchanalian Revel is this sort of innocent, joyous Pagan—maybe innocent is an exaggeration, but a joyous Pagan occasion. You know, everyone’s just sort of drunk and having a good time. It’s a dance in honor of the woodland god Pan. He’s the one with the sort of horned herm sculpture at the right of that composition. But then Poussin flips that exact same dance and gives it a different context within this story from the Book of Exodus, this story that’s about a grievous sin, a story that’s about the Israelite’s idolatrous worship, this ultimate violation of their pact with God. And exactly the same dance can have a totally different meaning.

CUNO: Now, you note in the catalog for the exhibition that dance as a subject disappears from paintings painted in the 1640s, the years of Poussin’s maturity. Why did that happen?

BEENY: That’s a wonderful question and I’m not sure we have an answer to it. There is maybe a little bit of a sense that as he progresses through the series of pictures for Richelieu, that he’s getting a little bit sick of it.

CUNO: You call it a signature genre.

BEENY: Yeah. Maybe he’s getting a little tired of it as a signature genre. I mean, in a very short pan, he paints the gigantic picture for the Buen Retiro; then he paints all of these high-stress works for Richelieu, who’s maybe a kind of scary guy to work for. There’s a sense that he maybe doesn’t quite finish The Triumph of Silenus, only parts of which appear to have been sort of carried to his customary degree of finish. And then at the end of the 1630s, he starts working on the first of his famous series of the Seven Sacraments, painted for Cassiano dal Pozzo. And I think he finds that work so intellectually absorbing and rewarding that it really takes him off in a different direction.

I think his return from Paris is a moment of real self-understanding, a real moment of clarity of what he wants to achieve as a painter; that he’s maybe ready to step away from official honors, in order to pursue avenues of exploration in his art that don’t have to do with decorating grand spaces, but that have to do with exploring moral and philosophical questions, large questions, in his art. And maybe dance feels a little bit frivolous to him for that reason, at that moment.

CUNO: What about this painting by Poussin, Rape of the Sabine Women, or so-called the Rape of the Sabine Women?

BEENY: So this is obviously not a painting of dancing. It’s an extraordinarily violent scene, an episode from early Roman history, as recounted by Plutarch and Livy. At left in red, we see the figure of Romulus, the first king of Rome. He and his men have decided, basically, to kidnap the women of the neighboring Sabine tribe, in order to bear their children and furnish future generations of Romans.

It’s really sort of the original sin of Roman civilization, in a way. So we see here the moment when Romulus lifts his cloak, in a signal to his troops, and they sort of set upon the Sabines, who had been invited to attend a festival, as a kind of pretext to lure them, to lure them to Rome.

This picture, though, presents this very violent episode in a kind of rhythmic frieze of rhyming poses. So we have the matching angles of the arms of the Sabine women as they reach upward and to the right, in the gestures of distress. Then we have the violent lunging poses of the Roman soldiers that often form perpendicular parallels to the gestures of the Sabines. There’s this very carefully-orchestrated system, a sort of geometric regime that contains the action here.

And that extends to extraordinary details in the painting. So I love to point out—this is something I only really noticed during installation—the Sabine woman in green who’s being kind of hoisted by the Roman soldier in a bronze helmet, her hair is bound with this ribbon that ripples off and to the right. And the little fringes that terminate that ribbon perfectly match the angle of her fingers as they’re extended in this gesture. So it’s just a feeling that no detail in this picture is forgotten and no detail is exempt from this kind of very carefully-thought-out, frieze-like formal system of organizing the violence that’s portrayed.

To me, it’s very interesting that this picture was painted for a French patron, Charles de Créquy, duc de Lesdiguières and Maréchal de France. He was a celebrated general and courtier, and he commissioned this picture during his posting to Rome as French Ambassador to the Holy See. But an interesting detail that emerged in my dissertation research about Créquy is that as well as being a soldier and a diplomat, he was actually a ballet dancer. Like many members of his social class in the period, he danced in ballets performed during the carnival season at the court of Louis XIII. And in the period, ballet training, along with dressage, along with fencing, was a sort of standard part of a French nobleman’s physical education, closely entwined, really, with military training.

And I think that’s really interesting to think about in terms of the famously dance-like or balletic quality of this painting. Scholars have always compared this painting to a piece of choreography, to a ballet, to a staged performance. And I think it’s interesting to think about the fact that, yeah, it was painted for a ballet dancer.

CUNO: Tell us about the role of wax figurines in Poussin’s working methods and what we’re looking at now.

BEENY: So Poussin seems to have really learned to model three-dimensional forms from his friend and roommate, the sculptor François Duquesnoy, right at the beginning of his time in Rome. And he ends up incorporating this sculptural practice into his method for composing his pictures in a pretty systematic way.

We have several contemporary accounts that tell us he used wax softened in the palm of his hand to sculpt small figures that he would dress with little scraps of cloth and arrange in a kind of box, a diorama, a toy theater, with specially-designed openings in the sides to emit light, a little hole cut into the front so he could peer in at his composition. And that’s how he would make his compositional drawings. I think knowing about this device, knowing about his use of wax figurines, goes a long way to explaining what a lot of his compositional drawings look like. These sort of schematic arrangement of figures with blank, ovoid faces that are dramatically lit and sort of whose forms are carefully described with washes of shadow.

CUNO: Sarah, I understand that one of the dancers, choreographers, particularly responded to this painting by Poussin, the Abduction of the Sabine Women, or the Rape of the Sabine Women, when we were talking about earlier. How did this happen?

COOPER: Yes, Chris Emile, who, you know, we reached out to for this project, we sat down with him, and Emily and I went through a slide show of all the pictures of the exhibition and hoped that he would find inspiration from some of these moments. And he was really drawn to this story of the Sabines. And he actually went online and tried to do some research and find out more about who the Sabine people were.

And really could find nothing about who they were, what their culture was, beyond this narrative of their moment of being under siege by the Roman conquerors. So this really inspired Chris to create a film, a piece of dance, that reimagined who the Sabines were— just to acknowledge them as people. As he very astutely noted, that throughout history, many groups that are colonized are often only remembered in history for their trauma. And he really wanted to give life to them before the moment of capture, and show them as a group of people with complex emotions, with complex experiences, with their own identities. And what really emerged in his film were these moments of tenderness between the Sabines, moments of fierceness, moments of shared sorrow. And what he does is he looks at the composition of the painting, as well, and incorporates this into the choreography. This sort of matrix of diagonals and intersecting figures, the sort of echoing patterns of lines are something that Chris echoes in the couples that he programs into his choreography.

He identifies two couples dancing with each other; but instead of in its moment of seizure, his Sabines are sort of intermixing with abandon and celebrating each other and showing agency over their own bodies, their own minds, and their own moments. Chris also really did an incredible job of looking at the textures of the textiles and the color palette in this image, and he builds these costumes that are a perfect blend of this Classical, ancient garments, but with all these details taken from contemporary streetwear. And it really dislodges his Sabines from any particular moment of time. They feel both in the future and in the past.

CUNO: Now, Sarah, you’re the Getty’s publication programs specialist. The two of you, Emily and Sarah, introduced videos of actual contemporary dancers into the installation of the exhibition. What does that tell us about Poussin and his paintings, that the dancers are represented in the exhibition?

COOPER: I think this represents an extraordinary opportunity for us to invite contemporary artists to find avenues for exploring these works that hopefully, will inspire our visitors to have new points of entry, as well to invite dancers who really have that lived and embodied understanding of dancing through space, of thinking about the positioning of their bodies in relationship to an aesthetic point of view, telling a visual story.

They are able to speak to sort of the dynamics that Poussin embeds in these pictures that perhaps many others can’t understand. Or at least they can give us a window into what it’s like to be thinking about bodies in space and invite us to imagine that, as well. It’s also an incredible opportunity for us to bring new perspectives that have not been previously explored, where these dancers are relating the themes, the gestures, the textures, the landscapes, the moments that they have found inspiration and locating in these pictures to their own worlds, their own identities, their own experiences within their communities. And that helps us bridge, something that is actually separated by a radical distance of centuries, of context.

The dance films are also an incredible opportunity for us to think about the tools of representation of dance. Painting would’ve been an important means of preserving that energy and telling that story. Today, video is at our disposal, and it is a new way of framing and investigating dance. And all of our choreographers really deeply engaged with the mode of filmmaking as part of their projects. So in addition to their choreography, they told a visual story through the frame, just one that comes from today’s point of view of today’s technology.

CUNO: Tell us about the three choreographers that you approached for these commissions. Why did you select those three among the many you could have selected?

COOPER: Well you know typically here at the Getty, I’m engaged in staging experimental and interdisciplinary performance events that take place out in our courtyards, in our gardens. Live events where we have an audience here on site, that really bring artists in conversation with our architecture and create this experience here at the Getty Center. So I’m always thinking about who are the artists working in Los Angeles that are creating some of the most exciting performances in both music and in dance, and in other forms.

So I was so thrilled when Emily reached out to me because I was able to tap into my regular practice as a programmer, my regular ongoing knowledge of researching our artist community, and draw out some of my absolute favorite practitioners who are working in Los Angeles today. Chris Emile is one of the choreographers I thought of immediately. We worked together on a couple occasions here at the Getty Center. He’s participated in performances with his dance company, No)One. Art House.

And they staged a performance here in 2018, where they actually brought their dancers throughout the water features here at the Getty Center, moving in our fountains and making these splashing moments, and also incorporating beautiful textiles and the environment. So I knew that Chris was doing great things as a choreographer, but also someone in conversation with the art world.

CUNO: So you’ve got three videos of the dancers that we can look at now. And as we walk over there, why don’t you tell us what about these artists attracted you to them. COOPER: I think it’s really interesting to note, that Emily and I began our conversation, you know, years ago, and that this project for Emily, I hope she doesn’t mind me saying, is also connected to her own background as a dancer, and that she has herself such incredible knowledge about dance companies and artists that have been working here in Los Angeles. So we really chose these artists together in conversation. I let her know about choreographers like Chris that I have been working with here at the Getty, but we also loved making a short list and look through all of the incredible work being done.

We also did think about having these performances be live moments here at the Getty Center, but of course, the COVID lockdown restrictions had us pivot to creating something for video. But that actually created this incredible opportunity for us to find a way to support and platform these dancers whose work is so vulnerable under the conditions of lockdown. So many dance companies in Los Angeles lost the leases on their spaces. So many, you know, had to stop performance entirely, which was a major source of their income. So just having this opportunity to create these commissions with them felt really special, and it was an honor to be able to do.

Micaela Taylor is also one of the choreographers that we worked with who was particularly inspired to film her piece here at the Getty Center. Micaela was someone who’s just a really exciting rising star in the dance world. She was on the cover of Dance Magazine in 2019, as one of the twenty-five choreographers to watch. And since then, she’s just been jam packed with major commissions and residencies in Europe and here. So we’re really excited that we got Micaela at this point in her career to be able to engage with us. She was very intrigued by seeing her dancers and her style of choreography in the environment of the Getty, and also in conversation with particular moments from the Poussin paintings.

CUNO: Now we have clips from each of the three videos on view here in the Getty galleries, but we also have links to them so that people can see them online.

COOPER: Yeah. In fact, what’s on view in the galleries is really just a preview of these full-length films that each of our choreographers made. Each of them are about fifteen minutes long. They really treated them as new works of art. In regards to Micaela, she was able to move her dancers through areas of the Getty Center that we never get to work with performance, because we did not have to worry about the safety and the spacing for the audience.

So we were able to put the camera on unique niches throughout the site. And for Micaela, her choreography is deeply connected to this idea of the glitch movement, or these very highly staccato gestures, these little freeze frames that her dancers move through. And what she does is she embeds in those moments lines from classical dance, from ballet, but they get sort of mixed into the freeform movement as it relates to her background in hip-hop and other dance forms. And it becomes this sort of slipstream between the classical and the contemporary, which was really interesting to think about in the context of this project.

And of course, our third choreographer, Ana Maria Alvarez, whose company the CONTRA-TIEMPO Activist Dance Theater, was a group that we were also familiar with from working here at the Getty Center with them in the past, but also their constant unique performances across L.A. and major venues where they engage with their community. And Ana Maria really was inspired by the Hymenaeus, the dance in honor of Priapus work of art that we looked at. But she also took an interesting approach by saying, “I’m not so interested in creating a work in response to Poussin.” So she said what she’s interested in her work as a conversation with Poussin. She really saw herself as reaching out to him, as two artists in conversation as equals. And what she creates is also an investigation of some of the same themes that we see in Poussin.

She uses as a common motif in her film, sugarcane and sugar, which is poured on the dancers or the sugarcane is ripped around and whipped or bitten into. And it was a meditation on this substance, sugar, this delicious and indulgent element that is also harmful or not great for our bodies. And this is a preoccupation that fascinated Ana Maria, that she also saw in this meditation on the revelry and the drunkenness that Poussin explores in his pictures of Bacchanalia.

CUNO: And what about the music we’re hearing with these videos?

COOPER: Each of our choreographers reached out to their own creative networks and brought on composers to create original soundtracks for each of the films. For Ana Maria, she worked with Anaïs Maviel, who also did bring in an ensemble of musicians to create this work. Chris Emile worked with an ensemble of composers, including AKUA and Bapari, Anthony Calonico, Keane Nwede and Alex Talan. And Micaela Taylor worked with the composer SCHOCKEY. And that’s the one we’re hearing now.

CUNO: Well thank you Sarah and thank you Emily for bringing Poussin and dance together in this exhibition in new and surprising and revealing ways. It’s an extraordinary exhibition and we thank you very much.

BEENY: Thanks so much for having us.

COOPER: Thank you.

CUNO: Poussin and the Dance is on view at the Getty Center through May 8, 2022. The exhibition was made possible by generous support from the Leonetti/O’Connell Family Foundation and is sponsored by City National Bank.

This episode was produced by Karen Fritsche, with audio production by Gideon Brower and mixing by Myke Dodge Weiskopf. Original dance films for Poussin and the Dance were commissioned by the J. Paul Getty Museum. Credits: hbny was directed and choreographed by Chris Emile, with music and score by AKUA and Bapari, Anthony Calonico, Keane Nwede and Alex Talan. Portrait was choreographed and edited by Micaela Taylor and directed by Silvia Grav, with music by SHOCKEY. CAÑA was directed and choreographed by Ana María Alvarez with music composition by Anaïs Maviel.

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

EMILY BEENY: One of the hopes of this exhibition was really to try to enlist visitors’ bodily exp...

Our theme music comes from the “The Dharma at Big Sur” composed by John Adams, for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003, and is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday, subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other podcast platforms. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts and if you have a question, or an idea for an upcoming episode, write to us at podcasts@getty.edu. Thanks for listening.

Comments on this post are now closed.