Buried by the 79 AD eruption of Vesuvius and rediscovered in the 1750s, the Villa dei Papiri in Herculaneum is one of the best-preserved ancient Roman villas. This expansive waterfront home of Rome’s elite contained bright wall frescoes, bronze and marble statues, delicate mosaics, and a library of over one thousand papyrus scrolls that were uniquely preserved by the volcanic debris. The Villa dei Papiri is also the model that J. Paul Getty used for his Malibu museum, now home to the Getty’s antiquities collection.

In this episode, curator Ken Lapatin and conservator Erik Risser discuss the exhibition Buried by Vesuvius: Treasures from the Villa dei Papiri at the Getty Villa, which brings sculptures, papyri, frescoes, and other artifacts from the Villa dei Papiri to Malibu.

More to explore:

Buried by Vesuvius: Treasures from the Villa dei Papiri exhibition

Buried by Vesuvius: Treasures from the Villa dei Papiri publication

Transcript

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

KEN LAPATIN: For the first time, with this exhibition, we’ve really brought the authentic artifacts from the ancient villa back to their home, because the original home is still buried underground and not visitable…yet.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with Getty Museum curator, Ken Lapatin and conservator Erik Risser about the exhibition Buried by Vesuvius: Treasures from the Villa dei Papiri.

The Getty Villa, in Malibu, was built by J. Paul Getty to house his art collection, it is now home to the Getty Museum’s antiquities collection. Getty modeled his museum on the Villa dei Papiri in Herculaneum, a seaside retreat with a library and art collection, that was buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. The Villa dei Papiri was rediscovered and partially excavated seventeen centuries later, and more recent excavations in the 1990s and 2000s have led to new discoveries about the structure and its art.

Buried by Vesuvius: Treasures from the Villa dei Papiri at the Getty Villa, showcases some of the extraordinary finds from Herculaneum, including objects which are now on view at the Getty Villa for the first time since their discovery. I recently walked through the exhibition with curator Ken Lapatin and conservator Erik Risser.

I’m standing in the inner peristyle of the Getty Villa with Ken Lapitan, curator of antiquities at the Getty Museum and curator of the current exhibition, Buried by Vesuvius: The Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum. From where we stand, we can look out onto the outer peristyle, with its long pool of water, leading onto a vista of the Pacific Ocean. It’s a beautiful setting, and it gives us a good sense of what it might’ve been like to stand within the original villa, looking out onto the Bay of Naples. Ken, thanks very much for speaking with me on this podcast. And congratulations on this moving and important exhibition on the Villa dei Papiri.

LAPATIN: Thank you Jim. We’re all very excited by the exhibition.

CUNO: And you should be; it’s a fantastic exhibition. So let’s start with Mr. Getty’s interest, perhaps even infatuation, with the original villa. What was his attraction to it and when did he first see it?

LAPATIN: Well, ironically, J. Paul Getty never saw the actual Villa dei Papiri, because in his day, it remained entirely buried underground. But he had been several times to Herculaneum. And on his last visit in 1971, while he was building the villa here in Malibu, he looked out and wrote in his diaries how fascinating it was to imagine the villa buried underground. He knew of the villa because of the stunning plan we’ll look at upstairs in the exhibition, drawn by the Swiss military engineer Karl Weber, who conducted the excavations for the King of Naples. And he knew of the excavations for the finds that Weber and his crew extracted from the tunnels they dug deep through the volcanic debris which are now star attractions of the National Archaeological museum in Naples, which Getty visited often. And we’re fortunate enough to have several in this show, thanks to the generosity of our Italian colleagues.

CUNO: Well, what was it about the original villa that attracted Mr. Getty’s attention to it?

LAPATIN: The original villa, although after ten years of excavation was reburied and abandoned, became increasingly famous throughout Europe, because it contains the largest sculptural collection from antiquity from a single villa. But especially because it contains the only library which preserves its scrolls known from antiquity. And these were extracted from Weber and his crew and entered collections of the Kings of Naples.

The Kings of Naples gave papyrus scrolls as diplomatic gifts, to the Prince of Wales and to Napoleon. They excited scholars. And so ironically, although the villa remained buried, it became more and more famous from its discovery in 1750 until its partial open-air excavation in the 1990s and 2000s.

CUNO: Uh-huh. Well, describe for us the Getty Villa, where we are standing, which of course, is meant to be what they imagined the Villa dei Papiri to have been. Describe the features for us.

LAPATIN: The Getty Villa is a very accurate one-to-one scale replica of the central core of the Villa dei Papiri. And that’s a large rectangular colonnaded peristyle courtyard with a large reflecting pool; a square inner peristyle, also surrounded by columns; and then a more traditional atrium block—meaning a kind of Roman house that had an open courtyard in the center and a pool to catch water. And these are the central features of the villa that was mapped by Weber underground, that Getty had reconstructed.

Karl Weber and his team, they actually remarkably, in the 1750s, extracted about ninety statues, which we have replicas in our gardens, as well, from the villa. They lifted some of the marble floors. They pulled from the walls, some of the wall paintings. So what we have in the villa decoration are copies of some of these floors, replicas of some of the wall paintings, replicas of some of the statues, to evoke that environment. But other details, such as the column capitals, the ceiling ornaments, the wall paintings, are taken from other Pompeiian and Herculaneum buildings. So our replica is a little bit mix and match; but it’s accurate in scale, it’s accurate in feeling, and it’s accurate to the Roman period, although not every detail of our building comes from the Villa dei Papiri.

And we know now from new excavations, there’s more at Villa dei Papiri that Karl Weber didn’t know, that no one has, here.

CUNO: Why didn’t they complete the excavations in the eighteenth century?

LAPATIN: They were expensive and dangerous. They were digging eighty feet below, through shafts and tunnels, fighting poisonous gasses. There were collapses. And after more than ten years, they had pretty thoroughly explored the site. They felt they had extracted what they could. Weber was getting ill from breathing this air with volcanic ash in it. And Pompeii had recently been found. And Pompeii, although buried by the same eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79 as Herculaneum, was buried much more shallowly by ash.

It was much easier to excavate. It was much less dangerous. So the Neapolitans shifted their attention to Pompeii, which eventually, today, became more famous than the smaller sister city of Herculaneum, although Herculaneum is better preserved and has given us more spectacular finds.

CUNO: So what is the state of the Villa dei Papiri in Herculaneum today?

LAPATIN: Well, renewed interest in the villa in the 1980s engendered new exploration. And then in the 1990s, reopening of some of Karl Weber’s tunnels. And then partial excavation of a corner of the building, maybe less than 10%, which really confirmed the accuracy of Weber’s excavations, helped us solidify the chronology of the building, which was in doubt. And we now believe it was built mostly around 40 BC, with some additions around 20 AD.

And most importantly, in some ways, new levels of the villa were discovered. Weber excavated a vast area, but only one floor. And we now have evidence for lower levels, including a beautiful seaside pavilion, where the owners could sit in their swimming pools and look out to the ocean.

But we found new statues, new frescoes, and spectacular ivory-veneered luxury furniture that we have on display in the exhibition here for the very first time.

CUNO: The building itself was buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD, and not rediscovered until the middle of the eighteenth century. How did they know to even look there to find the remains of the Villa?

LAPATIN: The area around the Bay of Naples was known to be producing antiquities since the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

CUNO: Wait, by producing do you mean finding—

LAPATIN: People—

CUNO: People finding them?

LAPATIN: People stumbled across them. And Pompeii, which was more shallowly buried, bits of buildings were known, but there weren’t systematic excavations until a young king took the throne in Naples, Charles VII. And he started sponsoring archaeological digs. And in 1738, he started sponsoring excavations in the town of Herculaneum. In 1750, not far from that work, well diggers were just digging a well deep below the ground, and they hit a stunning circular colored marble floor, of which we have a replica here in our Temple of Heracles.

And when they hit that floor, they realized they hit another ancient building. And the royal engineers took over the excavations under the patronage of the king, and they started digging the tunnels. So the Villa dei Papiri itself was found accidentally in 1750.

CUNO: Were there literary accounts of the villa?

LAPATIN: We have no literary accounts of this building itself, although we have over 1,000 scrolls found inside the building. But they don’t talk about the building itself. The scrolls are mostly poetical and philosophical texts, most of them relating to the ideas of the ancient philosopher Epicurus, about how to live a good life. The senatorial Roman owners of this luxury villa were asking some of the same questions we are asking today.

What is it to be human? How do we achieve work-life balance? How do we relate to one another? What is a good life? Should we fear death? Should we move forward with our lives, not worrying about the gods? How do we treat one another?

CUNO: Yeah. Well, let’s go inside the exhibition and then see what we can see.

LAPATIN: Great.

CUNO: So we’re standing now in a gallery, looking at the eighteenth century plan of the Villa dei Papiri. Ken, describe the plan for us.

LAPATIN: Well, this is a sheet of velum, drawn with ink and pencil and wash. It’s about four feet wide and two and a half feet tall. And it shows not only the plan of the villa, but the various tunnels that were dug by Karl Weber and his crew over the course of the 1750s.

Weber drew this by hand, and it includes the pools, the walls, the columns. And if we zoom in and look really closely, we can even see little sketches of statues of runners, of standing figures, of dancers, and a bunch of letters that are keyed to a legend that runs around the perimeter of this plan, which is written very clearly in Spanish, which was the official language of the Bourbon Court of Naples.

Before this date, there was great interest in antiquities throughout Italy and the world. People would pull them out of the ground and display them in their palaces or homes, if they could afford them. But Weber had an interest in the larger context, where these objects were found. And so far as we know, this is the earliest known archaeological excavation plan of any site in the world. This is the beginnings of scientific archaeology, such as it’s practiced to this day.

Weber excavated the site very thoroughly, but all through these underground tunnels, which you can see here in different colors. But the vast majority of the villa remains deeply buried underground and inaccessible, because the tunnels were backfilled by Weber and his crew to, one, alleviate the need to lift all that earth they were clearing up eighty feet; but also to help prevent collapses, because there were collapses. And people who were living above the excavations were very worried about people digging down underneath their houses.

CUNO: Yeah, because the city has grown over the site itself, yeah.

LAPATIN: Exactly. The modern city, called Resina in the eighteenth century, renamed today as Herculano, really still covers the villa.

CUNO: Yeah. And we’re referring to the villa as the Villa dei Papiri. That wasn’t its name.

LAPATIN: No. We don’t know what its name was. It’s also been called the Villa dei Pisones, the Piso family is the noble Roman family that we believe owned the villa, because the bulk of the papyrus scrolls were written by a philosopher named Philodemus of Gadara, a Greek who had been trained in the school of Epicurus at Athens, who emigrated to Italy and became a client of Lucius Calpurnius Piso, a very, very wealthy Roman aristocrat of an old noble family, who had held the highest offices in the Roman Republic, who actually married his daughter to Julius Caesar.

Caesar was marrying up. And Piso was the patron of Philodemus. So we believe for that reason that the villa belonged to Caesar’s father-in-law.

CUNO: Well, we have a bust of the son of the family here. Tell us about him.

LAPATIN: The Romans did capture portraiture, and in a style that derived from Greeks of the Hellenistic period, which we call a kind of warts-and-all style that’s very realistic. It’s not idealized. We see deep creases in the forehead, coming from the nose, the corners of the mouth, crows’ feet. And it’s Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus Pontifex, the son, who was the brother-in-law of Caesar, who we believe inherited the villa from his father.

Piso Pontifex served in the early Roman Empire as a very high imperial official, working for the emperors Augustus and Tiberius. He died serving as the Prefect of Rome. And he, and probably his older sister, Caesar’s widow, would have lived peacefully in this villa or another property. If you’re this wealthy, you have more than one house, I believe.

And they probably sat out the civil wars which raged after the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BC. We believe that Piso Pontifex probably built the small addition to the villa that reaches out to the sea, and probably continued the activity of Epicurean study at the villa, because some of the papyri postdate what we believe to be the death of Philodemus, and stretch into the early part of our millennium.

We don’t know who owned the villa at the time of the eruption in AD 79. We know from other sources that Romans bought and sold their homes with all their furnishings, including libraries. So the building could’ve been sold. But we don’t know that for certain.

CUNO: How likely was it that they could often come to the villa?

LAPATIN: They were probably headquartered in Rome. And in antiquity as today, in the summer Rome got hot and humid and crowded and unpleasant, and the wealthy would flee the city. And the Bay of Naples was their favorite retreat. And I kind of think of it like New York and the Hamptons. People would leave the city and go to the sea for the summer. Romans would shed their togas when they went to the Bay of Naples, and they would wear Greek dress. And the idea of cultured leisure— Otium, the Romans called it, the opposite of negotium, whence our word negotiate. Business is negotium.

But otium wasn’t just sitting by the pool and having drinks and nice banquets. It was part of that; but it was also discussing art, culture, literature, philosophy. What is the meaning of life? How can we be better people? And this is what the Romans did in their colonnaded gardens looking out at the sea, discussing these larger issues with friends. And this is the kind of thing that would take place at Roman villas. Not just the Villa dei Papiri, but around the Bay of Naples, and indeed, around the Mediterranean.

CUNO: Now, we’ve already mentioned that we refer to the villa as the Villa dei Papiri because of its library of papyrus scrolls. We’ve got three of those papyrus scrolls here in the exhibition. Describe them for us and tell us about the sort of mystery of how one might access the information within the papyrus scrolls.

LAPATIN: First, I have to say we are extraordinarily lucky to have these three scrolls, which really are unassuming at first glance. The German archaeologist and father of archaeology, Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who visited Herculaneum during the excavations in the late 1700s, saw these objects and described them as blackened and twisted like a burnt billy goat’s horn. These are incredibly fragile. They’ve never crossed the Atlantic before now. They were scrolls of papyrus, which is a plant material that originated in Egypt. They were the paper of antiquity.

And before the book in codex form, with sheets or pages, large scrolls that could be rolled and unrolled were the way texts were read. These scrolls have been carbonized by the heat of Vesuvius, which has paradoxically preserved them. Most papyrus from antiquity, except from ancient Egypt, with its very dry climate, have just disintegrated. This is natural material. These have been preserved by the volcano; but they’re embedded in a matrix of volcanic ash and mud.

CUNO: So what we’re looking at is not the papyrus itself; it’s what’s encased the papyrus

LAPATIN: Well, we’re looking at the papyrus still encased in the volcanic mud. So we’re looking at the two of them together. But if you look closely, you can see the concentric rings of the rolled-up scroll, if we look at it longitudinally. These papyri that are left in this form, unopened, are the most damaged, the most recalcitrant. Others were burnt to a lesser degree. There was greater opportunity to open them.

And one of the ways they were first discovered that they were even papyri, rather than lumps of charcoal or other things, down in the dark excavation tunnels, we’re told one of them was dropped and it broke open and people saw letters inside. And they were very excited to find lost books from antiquity. We know we’ve lost the vast majority of ancient literature. And people hope to find unknown plays of Sophocles or Euripides, lost books of Roman history by Livy, or the great works of literature.

So there was an attempt to open the scrolls. And in the early days, this was disastrous because they’re so fragile. They were broken open. It was tried to put them in gasses or pour mercury over them to separate the different layers of the papyrus.

And they were first found in 1752; and by 1753, the Neapolitan court sent to the Vatican for help. And the keeper of the Vatican’s manuscript collection, Father Antonio Piaggio, came to Naples to help for what was thought to be a few months.

And he spent the rest of his life in Naples, trying to unscroll these. And we have on display from the National Library in Naples, this wonderful piece of eighteenth-century furniture, father Piaggio’s unscrolling machine, which is a kind of traction system. The edge of the papyrus scroll would be attached with glue very gently, with silk threads and gold beater skins, strips of sheep or pigs’ intestines, and the weight of the papyrus scroll would be used to unscroll it, to lift it centimeters at a time.

This was a very long and laborious process. But over the years, as more and more of the scrolls were opened, the scrolls, more and more, were these philosophical treatises of Philodemus. It was harder to read, and the work became more and more of interest only to academics.

One of the most exciting things for me in this exhibition is that since 1750, with Weber’s underground excavation, with Piaggio’s technological advances to open, we see the Villa dei Papiri being a site of cutting-edge technology applied to archaeology. The same is happening today. These three scrolls, before we put them in their cases here at the Getty Villa, they made a detour to UCLA, where at the dental school, they were put in a very high-tech micro CT scanner, as part of an ongoing attempt to virtually unwrap them noninvasively, without ripping and tearing them, as Piaggio’s machine inevitably did. To unscroll them and look inside them and read their texts with no damage virtually. And this is something that’s being pursued, with the Getty assisting the National Library of Naples, and computer scientists at the University of Kentucky.

CUNO: Now, tell me how that works. Because I would think, since you can’t unroll them, that you’re going to be seeing if you can penetrate the layers digitally, as you’ve just described them. You’d see layer upon layer upon layer upon layer of text. So how do you separate the layers of text, one from another?

LAPATIN: Well, we have on display a video. And it’s really using medical technology, the technology of a CAT scan, where a very, very high resolution 3-D x-ray is taken. And then through computer algorithms, the different layers of the scroll are distinguished and the papyrus roll can be virtually unscrolled. It’s the kind of technology that doctors use to look at your organs by manipulating the data from the scan.

The real difficulty with the Herculaneum papyri is to also bring the text along with the papyrus. And the black ink against the charred scrolls, even on an open papyrus, is difficult to read. And we have an example in the exhibition of an open papyrus that really looks like a charred piece of toast. And with great difficulty, standing at the right angle, we can distinguish tiny black ink against dull black charred papyrus. Through multispectral imaging, by manipulating the light wavelength to the infrared range, we can separate the papyrus from the ink and make that ink pop.

So the plan of the computer scientists is to use the open papyri to create a dataset, and to train computers, through machine learning, to recognize the key features that separate ink from papyrus, and then apply that to the images from the CAT scans. And then to read them virtually.

CUNO: So the villa is famous for its library, for its papyrus scrolls, but also for it’s sculpture.

LAPATIN: Absolutely.

CUNO: Is it equally important for its sculpture?

LAPATIN: Well, certainly for archaeologists and art historians, the sculpture has great importance. And one of the things I’m very pleased [about] is in this exhibition, we try to bring together the literary, the philosophical, the papyrological, with the art historical and the archaeological, the sculpture, because the two help inform one another. They existed in the same place, people would read the scrolls, or probably have scrolls read to them by servants or enslaved peoples, as they strolled in the gardens looking at the sculpture.

In front of us we have this stunning statue in marble, about two meters tall, of the Greek goddess Athena, Minerva to the Romans, her arms outspread, wearing a long dress, a helmet, the protective egis with the talismanic head of Medusa on her shoulder. She was the first in battle, she was the protectress, but she’s also the goddess of philosophy. And she stood at the hinge point of the ancient villa, in the room between the inner and outer peristyles.

She’s lost her paint. But we hope through, again, different imaging techniques while she’s here, to study her and understand better her full decoration.

CUNO: Now, she’s identified as Greco-Roman. How likely was it that there was Greek sculpture at the Villa dei Papiri?

LAPATIN: This is a good question. We have only one statue that has an artist’s signature. It’s around the corner. It’s signed by an Athenian artist. His name is Apollonius, the son of Arceus of Athens. We know of his father and grandfather from not surviving sculptures, but surviving statue bases with their signatures, in Greece. And they came from the town of Marathon, which we all know is twenty-six miles outside of Athens. But Apollonius signs as an Athenian, not as a Marathonian, which makes us think he wasn’t working at home. He was working abroad and using the main city, rather than his local location, as the identifier. So we think that most of these sculptures, although some were carved of Greek marbles, were made in Italy because after the fall of Greece to Romans, Rome was the market, and we know artists immigrated. But it’s also possible that some of the statues were acquired by Piso when he was governor of Greece and living in Greece, but we can’t be sure.

CUNO: Yeah. It looks to be self-consciously antique. And that is that it was something that would have attracted the attention of a visitor, as if it were a Greek original.

LAPATIN: Well, Jim, your art historian’s eye has picked up exactly. This is an archaizing figure. Its style harks back to an early Greek period, with the stiff symmetrical swallow-tail folds, the somewhat flatness of the carving.

CUNO: And it’s over life size.

LAPATIN: It’s over life size. And the early reports of excavators said it was gilded. We don’t see traces of gold now with the bare eye, but we’ve just gotten her up and on display, and on closed days like today, our conservators plan to look at her with microscopes, with special lighting, to try to see what we can find of traces of her decoration. But if she was gilded, she may have been a kind of what we would call pseudo chryselephantine, a faux gold and ivory statue, harking back to the great cult images of Classical Greece.

CUNO: Right. Now, it’s not surprising that we would have in the exhibition and from the Villa dei Papiri, because of its library, busts of philosophers. And there are four here in this gallery. Describe them to us and what role they might play in the life of a villa.

LAPATIN: These are four small bronze portrait busts, ranging from maybe six to eight inches, of philosophers. And they’d be things you’d sit on shelves or tabletops. And they’re all inscribed with the names of these bearded figures. Three are philosophers and one is an orator.

We have Epicurus, the founder of the Epicurean school. He founded a place called the Garden, which was different from many other philosophical schools, in that it wasn’t closed by rank. It was open to women, it was open to slaves. And Epicurus followed earlier philosophers in believing we’re all made up of atoms, and we come together and we dissolve. And the gods, if they exist, aren’t concerned with human lives, so we shouldn’t fear the gods. He also thought we shouldn’t fear death, because while we’re alive, death is absent. And when death comes, we’re gone.

The papyri preserve Epicurus’ four-part cure, which we’ve put up on the wall: Don’t fear gods, don’t worry about death, what is good is easy to get, and what is terrible is easy to endure. Epicureanism was misunderstood in antiquity as being the pursuit of pleasure and gluttony. But pleasure for Epicurus was the absence of pain. It was obtaining modest pleasures, being with your friends, having good food. Because if you’re hungry, that’s a pain. But it wasn’t about excess. And so we have a portrait of Epicurus, the founder of the school, inscribed in Greek, Epicurus.

We have a portrait of his successor, Hermarchus. We have a portrait of Zeno. And there were two philosophers named Zeno. One was the founder of a different school, the Stoics. And this seems to be a portrait of that philosopher, because we have other portraits of him. But Zeno was also an Epicurean, a different Zeno. And he was the teacher of Philodemus. So this Zeno might’ve been mistaken for the Epicurean Zeno. Not by Philodemus, but maybe one of the later owners of the villa.

And we have a small portrait of Demosthenes, the famous Athenian orator who fought against tyranny and was famous for his civic duty and integrity. So these provided models of behavior. Actually, there were three portraits of Epicurus at the villa. That’s how important he was.

CUNO: Was there a dedicated room in the villa for the papyri that we would call a library? And would these sculptures have been in that library?

LAPATIN: There’s a room that’s often called the library; but more and more, we’re thinking we shouldn’t be using that term, ’cause it’s really more of a closet. It was really more of a stacks, a storeroom. And that’s where most of the papyri are. The library room is at the back of the villa, in a part of the villa that was not replicated by J. Paul Getty. But the scrolls were also found to the front of the villa, near the peristyles. And that’s where you’d go to read.

So you’d take your scrolls and you’d bring them to a pleasant place, and that’s where you could read them, outdoors or in the shaded colonnades, or have them read to you. And the portraits were found in a room nearby there. So that might be the difference between your library stacks and your study. And so the philosopher portraits were found in close vicinity with some of the other scrolls found outside that storeroom.

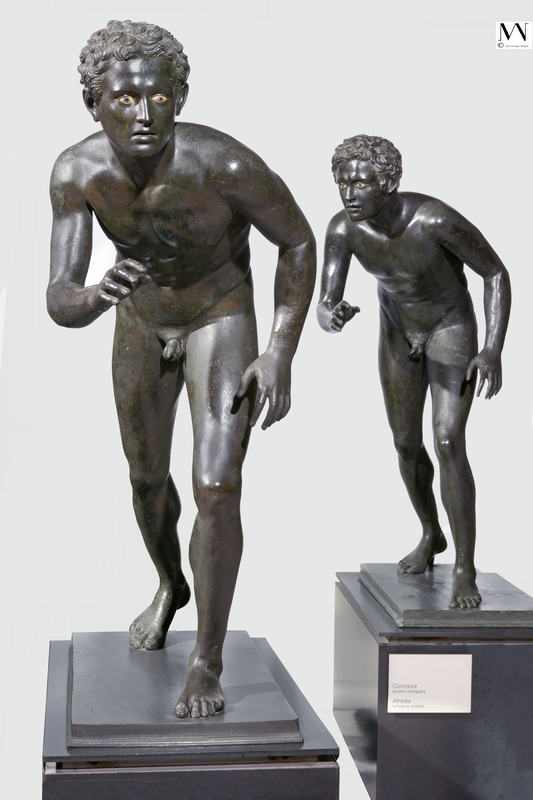

CUNO: Well, take us now to these great sculptures of the running youths, and what role these might’ve played in the iconography of the villa and its collection of sculptures.

LAPATIN: The gardens of the villa were really populated with sculptures. And we have large-scale portraits of philosophers, of kings, of politicians, of gods, of heroes, and of Dionysiac figures. And among all that, at the ends of the long peristyle, were two statues of nude youths posed as if they’re at the start of a race. Not crouching today, as our sprinters, but standing, about ready to spring forth, like long or middle distance runners.

CUNO: The marathon runner, for example.

LAPATIN: Yes. And in fact, because they were knocked over by the force of the volcano, and sketches of them appear in Weber’s plan, we know generally where they were found, but not how they were oriented. And some scholars have believed that they actually represent wrestlers, the way they stand, and have them facing one another. But I believe and other believer they’re runners poised at the start of the race. And they’re very tense. One is staring straight ahead. The other is sort of looking nervously to his right, sort of checking his opponent at the start of the race.

And meaning of this is various. This is all really open to interpretation. We know of the Roman dictum men sanum in corpore sano, a sound mind in a sound body, how important exercise was. And the Roman peristyle garden kind of recreates the environment of the Greek gymnasium, which is not only an athletic training ground; it was a school, like the German gymnasium today, where literature, philosophy, and history would be taught. So these would be all-rounders. And the figures of these runners in the garden helped to evoke that idea of the gymnasium.

We know from Latin literature that Roman aristocrats often created in their villas, features evoking Greek spaces, like a gymnasium or like the Canopus of the Nile. So figures like these runners would’ve helped bring them to ancient Greece.

There’re also more erudite theories about the course of life, running for victory, what you gain. But these are not really attested in ancient literature. But all of the sculpture of the villa would’ve been provided to allow for talking points. As you’re walking through the villa with your friends, as we’re walking through the exhibition now, you could discuss the virtues and vices of specific individuals, how they provide models for behavior, both positive and negative, so we can become better people in our lives. And these very powerful figures of young men in their prime provide us with models for how we might live our lives.

CUNO: Now, they’re next to two female sculptures identified as dancers. Tell us about them and how they would’ve been seen within the villa.

LAPATIN: Well, this is very controversial because Weber plots the find spots of five of these female figures. We’re lucky enough to have two of them on display, and we’ve put graphic displays of eighteenth-century engravings of the three we don’t have on the wall, so visitors can get a sense of all five.

According to Weber’s plan, these were found in the outer peristyle, behind columns. Which really isn’t where we think statues should go. And because in the inner peristyle, along a fountain, there’re little niches of semicircular form, where their semicircular bases seem to fit exactly. Some archaeologists and art historians, including Mr. Getty’s archaeological advisor, thought they might belong. So we at the Getty Villa have replicas of these statues not in their archaeological find spots. They’re here in the inner peristyle, not far from the runners.

When they were found, they were conventionally called dancers. But their feet are flat on the ground. They’re really not dancers. We call them “dancers,” in quotation marks. Their lower bodies are static, although they all have one leg straight and one leg bent, with one knee poking through their columnar drapery. But their upper bodies are all different, with their arms in different positions. Some of them are playing with their dresses, others raising their hands. One seems to be raising her hand high above her head. Maybe she was holding a water jar on her head. So they’ve been identified variously as dancers, vestal virgins, basket carriers, jar carriers, and nymphs. And they’re often identified as mythological figures, the daughters of King Danaus.

I believe that they’re actually representing the nymphs of the Aqua Appia, the earliest of Rome’s aqueduct. They have very well-preserved inlaid eyes. They’re made of, we believe—but we’re gonna look at them more closely—of bone and stone and glass. But this figure has wonderful metal inlays in her bronze. She has a series of…

CUNO: Is it copper?

LAPATIN: …copper in her bronze, red copper, of rays along the hem of her garment, the bottom of her dress. And she also has a headband with copper and silver inlays. And other statues even have tin teeth or coppered lips to make them look more lifelike. But of course, this dark greenish-blackish color is one that is not reflecting their original appearance in antiquity, but is the result of the heat of the volcano and then restoration activity in the eighteenth-century.

CUNO: Now, once again, these look archaic, self-consciously so. Is that true?

LAPATIN: Very much so. This is again the Romans harking back to the golden age of ancient Greece. Maybe a parallel is the way that the great capitalists of nineteenth century New York—the Fricks, the Carnegies, Rockefellers—built huge buildings, their own palaces, in Italian Renaissance style, to style themselves as great potentates of the past. This is what the Pisones and their counterparts, the ancient Roman senators were showing—their learning and their culture and their understanding of ancient Greece, as well as their great wealth—by collecting these works in the Greek style.

CUNO: Mm-hm. Now, there’s some more sculpture over here, some bronze and marble sculptures. How common was it to mix marble, with the darker bronze sculptures? Was that something that was common at the time?

LAPATIN: Well, yes. One problem for us, Jim, is that bronzes tend not to survive. The bronzes we have, we have mostly through accident, through some disaster, because bronze is a metal—it’s an artificial alloy of copper and tin and often lead, sometimes other alloys. But it can be melted down and reused. And so in hard times, the bronze sculptures of antiquity, even in antiquity, were melted down to be reused for shields and buckets and swords and hinges.

And most of the bronze sculptures from antiquity, thousands and thousands, were melted down. And we have references to them in ancient literature, we have images of them in ancient painting, and we have lots of statue bases. But over the course of time, they’ve been melted down. It’s the volcano that buried this villa that kept these bronzes from being melted down. We have many more marbles than bronzes today. And the villa is an interesting site for investigation because here, we have twice as many bronzes as marbles.

Is that because they’re more expensive and the owner was showing off his wealth? Or is that because they were less expensive? Because they could be made through models and casts, and they could be churned out, whereas the marbles all had to be carved by hand. So we’re still investigating the relative values of bronze and marble in antiquity. But they were shown side by side.

CUNO: Well now, here we have this extraordinary sculpture called the Drunken Satyr. It’s really the sort of pivotal point in the exhibition. And it’s been the subject of conservation work by Erik Risser, who’s here, associate conservator here at the Getty Villa, who worked on this sculpture for months, because it was part of the arrangement that we had with the museum in Naples, that we would work on the sculpture to restore it. Because it was restored when it was discovered in the eighteenth century, and had not been restored since then. Is that correct?

ERIK RISSER: It’s somewhat true. It’s been mildly adjusted since it was restored in the mid-eighteenth century. So we do know archivally that, you know, the piece was discovered in 1754, and that the restoration occurred roughly between 1754 and 1759.

CUNO: Well, describe the sculpture for us before we get into the conservation work.

RISSER: What we see before us here is, you know, as opposed to many of the other bronzes and many of the other sculptures in the exhibition, is very much a horizontal sculpture, whereas most other things are vertical. But at the same time, what you have is a very dynamic moment of a middle-aged satyr—we know it’s a satyr because you have the little horn buds up on the skull, as well as the wattles and pointed ears.

You have this satyr, often associated with Dionysius, with Bacchus, in the process of having fallen backwards in a drunken stupor. So during basically a festival, in a moment of ecstasy or excess. And he’s fallen onto a wine skin and a lion pelt that’s underneath that. But what you’re seeing here is very much this moment sort of, flash frozen, of someone falling backwards and in the process of rebalancing themselves, but also saying, ‘I’m good. I’m okay.’

So you have this hand raised in this great pose where he’s snapping his finger and he’s grimacing. And this grimace is not, you know, anything to be afraid of; instead, it’s this grimace of satisfaction and of release. Whereas as the same time, in that sort of relaxation, which you do sort of see in the belly slightly shifted off to the left, you also have this moment of tension, with the raised right arm and the raised right leg, which is a rebalancing. So you really have this moment of tension and relaxation really captured in this one figure.

CUNO: So what were the challenges for you as a conservator in working on this sculpture?

RISSER: Multifold, I think is the easiest way to respond to that. But you know, the piece came to us. We knew that it was in somewhat of a fragile state, but it had many things that were not defined. We knew that it had been heavily restored, of course, between 1754 and 1759; but the full nature and the degree of the restorations, we did not fully understand. Like with most conservation projects, the first and oftentimes one of the most substantial phases is really about information gathering, archivally working with our curatorial colleagues to understand what we know of the piece and how it was described and what is written about it, in terms of potentially who worked on it, what they did to it.

So through the study process, we were able basically to identify what is ancient and what is not ancient, sort of using that as our basic roadmap. And looking at that, what you see today is very much a composition that is a combination of the two. But everything that the satyr is on is overwhelmingly eighteenth century.

CUNO: “Satyr is on,” you mean the stone plinth or the stone column.

RISSER: Yes. The stone plinth is eighteenth century. In reality, what you’re looking at is you have a full satyr figure, you have a portion of the wine skin, and a portion of the lion pelt that are ancient. Everything else that you’re seeing is very much an eighteenth-century conception, based on, to some degree, making it work with his posture; but also to a great degree, responding to the tastes of the time, and also other objects of this type being known.

CUNO: So what did you do? You took it apart?

RISSER: We did.

CUNO: Cleaned it up?

RISSER: Yeah, we took it apart and cleaned it up, sort of, a very quick summation, yes. But through the study, was really to identify, again, what’s ancient, what’s not ancient. But more specifically, are there structural issues that are, to some degree, not easily seen on the outside?

So using multispectral imaging, we of course were able to sort of see the different types of surface morphologies. Is there chemical instability happening on the surface? We’re looking using microscopes. But more importantly, through radiography, we’re able to actually sort of identify the ancient, non-ancient. But also, how are the ancient pieces brought together, and were those compromised during the eruption, envelopment, during the corrosion, or shall we say burial process? You know, how did the bronze basically weather? And then significantly, after it was excavated, what alterations happened during restoration?

What we can say definitively from those studies is that the satyr is ancient, but both of the right legs were pretty heavily damaged and repaired; however, they were not detached, unlike both of the arms, which were detached and had to be rejoined.

Now, whether the raised right arm actually was detached during the envelopment from the pyroclastic flow or whether it was more convenient to remove it in order to allow it to traverse tunnels and then be brought out onto the surface is something we can’t fully say. But we can say definitively that it was actually detached

CUNO: Well, the arms are really convincing. And that is, the gesture and the relationship of the arms to the body. Do you have any thoughts that they might have been put on incorrectly or they might be eighteenth century fragments?

RISSER: For the most part here, they look to be correct. Now, as to whether the posture of the overall figure is correct, it’s probably slightly over rotated. It should probably be slightly rotated more forward, to some degree. That’s indicated by the slouch of the belly, as well as, you know, basically how the right leg is rotated. He might have actually been turned over a little bit more in his ancient context.

CUNO: Was it common, and would it have been the case in the original Villa dei Papiri, that the sculpture would’ve been on a stone plinth, as it is today? Is that meant to imitate the Roman era plinth, or was it something that was a fiction of the eighteenth century?

RISSER: The assumption is that of course, it would’ve been on a stone base. We can’t say precisely, because of course, this is not the ancient base. You know, here, what we can say is that you did have a metallurgical join at the left elbow, as well as in the lower back, which show areas where you have the trauma of the envelopment, where the piece was actually ripped from its context. So of course, you have some of the wine skin, some of the lion skin. Where the rest of it is, as well as the stone, we still don’t know. But yes, this should be somewhat very much of an approximation of what we had.

CUNO: Yeah. Now, we have a copy of this here at the Getty Villa, and it’s in a pool in the outer peristyle, suggesting that it’s sitting on a rock within a body of water. Would that have been how it would’ve been shown at the Villa dei Papiri? Do we know the find spot for the object?

RISSER: Yes, we do.

CUNO: Yeah.

RISSER: And that is approximate to where he was recovered, based on Weber’s plan.

CUNO: Well, it’s a fantastic thing and it’s a beautiful sculpture. Having mentioned that there’s a replica here at the Getty Villa of the Drunken Satyr brings us to the question of the replicas here at the Getty Villa. Was that part of Mr. Getty’s own conception of the Getty Villa, that it would have these replicas, Ken?

LAPATIN: Yes, very much so. In the late sixties and early 1970s, when Mr. Getty realized that his ranch house, which was the original Getty Museum, was too small for his collection, and he began to think of either expanding the ranch house or— and his advisors said, ‘Better to build a new building,’ because the ranch house was becoming very labyrinthine. He had different ideas of a historical recreation. He wasn’t a fan of modern architecture. And he thought because much of his collection was antiquities, he decided that a building in an ancient form would serve to contextualize his own collection.

And he had two villas in Italy of his own that he lived in, and he had spent a lot of time in the Bay of Naples, and he knew of the Villa dei Papiri, and he decided to build a replica of the building for his collection. And at that time, it was suggested to him that he might engage the historical Chiurazzi Foundry in Naples, which made replicas of the sculptures, to populate the gardens of his villa with the same sculptures that populated the Villa dei Papiri. And the Chiurazzi had made, for grand tourists and others, these replicas of the most famous pieces—the runners, the dancers, the satyr. But Mr. Getty commissioned the largest group of these figures the foundry ever made. And we have almost a complete set of the bronzes from the Villa dei Papiri. And so we’ve brought to the Getty Villa not only the originals of many of the pieces we have replicas of—and from the exhibition galleries, you can look out the window into the inner peristyle and see some of these bronzes near their original find spots.

But we also brought the marbles, we brought frescoes, and we brought newly-excavated material that was unknown to Mr. Getty, that was only found in the late nineties and the 2000s, which is yesterday in archaeological terms. So we have the earliest finds and we have the most recent finds from the villa, some of them never displayed before.

CUNO: Well now, this last gallery is dedicated to new finds, new discoveries at Herculaneum. Tell us about these, Ken, and tell us about the prospect of yet more finds to be found.

LAPATIN: Well, the excavations of the eighteenth century covered a lot of area and were very thorough; but they only covered one level of the villa. And in the 1990s and early 2000s, cleanup operations and some new explorations not only recovered those early excavation areas, but also found lower levels where stunning frescoes and marbles and unique ivory-veneered wooden furniture have survived. And thanks to our partners at the Parco Archeologico di Ercolano, we’re able to show some of these most recent finds.

And perhaps the most important of them is this spectacular figure of a goddess leaning on a pillar, with wonderful drapery, with a lot of painted decoration surviving on the hems of her garment. Even her eyes have painted decoration. And this is again, the Romans emulating ancient Greek sculpture of the Classical period in a virtuosic fashion.

CUNO: Now, she’s centered in the room, but just beyond here is a wall. And on the wall is this extraordinary fresco painting, or fragments of fresco painting, showing architecture and architectural reliefs, through a sequence of windows and spaces, with a kind of complex geometry that one wouldn’t have expected, I think—at least I wouldn’t have expected—at the villa. Describe this for us, and also the role that fresco wall paintings would’ve played.

LAPATIN: Right. This is a large fragment, recomposed, of broken bits of fresco that have been detached from the wall, and that’s why we could bring it here. And it’s kind of an architectural fantasy. We see columns and shelves; we see a large glass bowl full of grapes and summer fruit; we have a window looking out into a vista, where we see a colonnade, as if we’re looking into a Greek sanctuary. Leaning on the wall is a shield with the image of Medusa reflecting. This is illusionistic architecture.

The illusionistic 3-D trompe l’oeil architecture in this painting would open up a rather closed room, giving dimension to the wall and expanding the space. It’s the first time this fresco is on display anywhere. But similar work from other ancient sites have inspired the decoration of our peristyle garden here at the Getty Villa.

CUNO: Yeah. Now, Mr. Getty was a micromanager, shall we say, of things, including of the building of this museum that he had designed. But he never visited it, is what I understand. Is that correct?

LAPATIN: Yes. Mr. Getty, he left California in the early fifties, and he established himself in a large Tudor manor house, Sutton Place, outside of London. It was more convenient for him to run his international oil empire from the UK than from the West Coast of California. And although he was a very avid traveler early in life, with age, he developed a fear of flying. And so he micromanaged the building and decoration of the villa long distance, through films, photographs, letters, telegrams. He always intended to return. And he, of course, as you know, did return posthumously. He’s buried on a private plot on the villa property.

Getty’s vision was really a large one, because it wasn’t just the building, it wasn’t just the statuary, it wasn’t just the frescoes; it was also the gardens themselves. The plants in our gardens, Getty had transported originally from hothouses in Italy. It was the location. Getty had lived in the Bay of Naples, he had visited these sites, he knew them, and he thought the California coast, the sweeping Bay of Santa Monica, apart from the absence of Mount Vesuvius looming over Naples, it’s really reminiscent of the Bay of Naples and Campagna. The climate, the herbs. And so visitors here have the sea breezes that were present at Herculaneum. You can hear the birds, you can smell the herbs.

It’s better than virtual reality, because it’s a reality where you can feel the spaces. You can physically breathe the air, smell the smells, hear the birds. And now for the first time, with this exhibition, we’ve really brought the authentic artifacts from the ancient villa back to their home, because the original home is still buried underground and not visitable…yet.

CUNO: Yeah well, Ken, that’s a great way to end the podcast interview today. So thank you very much, Erik and Ken, for what you’ve done in bringing this exhibition to life, but also for participating in the podcast.

LAPATIN: Thank you so much, Jim.

RISSER: Yes, thank you, Jim.

CUNO: Buried by Vesuvius: Treasures from the Villa dei Papiri is on view at the Getty Villa through October 28th, 2019.

Our theme music comes from “The Dharma at Big Sur,” composed by John Adams for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. It is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts or Google Play Music. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts. Thanks for listening.

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

KEN LAPATIN: For the first time, with this exhibition, we’ve really brought the authentic artifa...

Music Credits

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.