At the start of the twentieth century, American printmakers portrayed the modernizing world around them, from towering skyscrapers and deserted city streets to jazzy dance halls and boisterous movie theaters. Many of these printmakers were recent immigrants to the United States, and many were women—that these groups in particular could make careers as artists is indicative of the immense social changes of this period.

In this episode, Getty curator of drawings Stephanie Schrader and the Huntington Art Museum’s Bradford and Christine Mishler Associate Curator of American Art, James Glisson, explore this topic as they walk through their exhibition True Grit: American Prints from 1900 to 1950.

More to explore:

True Grit: American Prints from 1900 to 1950 exhibition

True Grit: American Prints from 1900 to 1950 publication

Transcript

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

STEPHANIE SCHRADER: They’re taking to the streets, they’re not just working for wealthy patrons and thinking about elevated topics, they’re looking at the now, the mundane, the uninteresting, and making it memorable and circulating for everyone to enjoy.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with Getty drawings curator Stephanie Schrader and Huntington Museum curator of American art James Glisson about their exhibition True Grit.

The first decades of the 20th century saw a diverse range of American artists embrace printmaking to depict the dark, shadowy forms of towering urban skyscrapers and the crowded circumstances of city life. Many of these artists were women, and many were recent arrivals from foreign countries. That they turned to printmaking was in part due to its popularity and low cost, but also to its dark, expressive, linear effects.

The Getty exhibition True Grit: American Prints from 1900 to 1950 shows a post-war and depression-era America at work and play, from dance halls and late-night assignations in the park to nighttime swims and walks through empty, cavernous, shadowy city streets.

To learn about modern American printmaking, I spoke with the exhibition’s curators, the Getty’s curator of drawings, Stephanie Schrader, and the Huntington Museum’s Bradford and Christine Mishler Associate Curator of American Art, James Glisson.

Thanks for your time this morning, Stephanie and James. We’re standing in the midst of the exhibition, True Grit: American Prints from 1900 to 1950. Tell us about the beginnings of the exhibition and why the Getty Museum is mounting an exhibition of American prints given that it doesn’t collect prints or, for that matter, American art much at all. Why American prints and why now?

STEPHANIE SCHRADER: Well, thanks for that question. So I’ve been here since 2001 and I spent my time thinking about European art for 18 years and I thought, you know what, it’s about time that we think about something other than European art here at the Getty.

We have an incredible photography department that looks at American art, but the rest of our collection doesn’t really think about America. And considering that we’re in Los Angeles, which is one of the most vibrant cities in America I thought it was time that we turned our eyes to look at things that our visitors might not expect. So I wanted to surprise them to see the boxing and tenement life and working closely with women in kitchens and peering into windows in New York City.

And I also thought, given all of these conversations that we’re having about diversity, about racism, about sexism, about poverty, about political cronyism, those were all conversations that were happening back in early parts of modern America and our public would find these interests and topics interesting relevant today.

CUNO: Where did you find the prints that you borrowed?

SCHRADER: Los Angeles has an incredible collection of early 20th Century American prints in the Hammer, in the Huntington, and at LACMA and also in private collections. So it wasn’t hard to find these things but what I needed to find with the collaborator and that’s where I found James who works at the Huntington and looks after this material.

CUNO: Tell us about the American collection at the Huntington, James.

GLISSON: So I’m the Bromford and Christine Michler Associate Curator of American Art at the Huntington. And the Huntington has always collected material around the history of the United States, but Huntington himself didn’t get around to collecting American art in a kind of serious way. So American art came to the Huntington in 1984 as the result of a large gift from the Virginia Steele Scott Foundation. So the Huntington became a West Coast center for the collecting and exhibiting of historical American art.

CUNO: Very Good. Now you titled the exhibition, Stephanie, True Grit. I assume that’s a reference both to the gritty nature of the print processes themselves, that is the marks left by etchings, engravings, and lithographs, and also the subject of the prints, tenement housing, dance halls, boxing rings, the city at night and those that you already mentioned. Tell us how you came up with the title “True Grit” and what you meant by it.

SCHRADER: OK, so most people think that I named this exhibition after the 1968 novel, [CUNO: That was going to be my next question.] True Grit, and the movie but that actually had nothing to do really with the title. It had to do, like you say, with the texture of these prints and the subject matter, and this term, “true grit,” James did some research and found out that in fact it’s used in the 1920’s. It’s really talking about perseverance, toughness, the ability to like get by and maneuver in these difficult crowded cities. It has a relevance to the actual subject matter.

CUNO: Show us where there’s evidence in that particular print.

SCHRADER: Ok. So I think we can do it here with Stag at Sharky’s. I started the show with this image as to the way people walking down the hall, turn their head and they see people boxing.

CUNO: What was Sharky’s?

SCHRADER: Sharky’s was a club. Tom Sharky had a club and that’s where you saw boxing matches happen. Boxing, when George Bellows who made this print, it was based on a painting he made in 1906 and when he made that painting boxing was illegal so you could only go see these events in private clubs. And George Bellows had a studio right down the street from Sharky’s and in the urge to go out and see the streets and see what’s happening in the world around him he found himself in this club. And found himself watching what he described as two men trying to kill each other.

And so that toughness, that grit, that American spirit of perseverance and fighting your way to the top, I think sort of is symbolized in this print. And also the texture that you see in the lithograph here, the roughness of the lithographic crayon and all sorts of different shades of black, white, and gray all coming together to like push these figures who are fighting into our space.

CUNO: And it’s related to a painting, as you mentioned, and maybe James you can tell us about this. Why make a print after a painting if the painting indeed came first?

GLISSON: So Bellows makes three paintings of boxing a few years before he makes this lithograph. But Bellows understood the power of lithography to distribute images in a mass way.

CUNO: [Over Glisson] Because you can take almost an infinite number of impressions.

GLISSON: Exactly. And scholars estimate there are editions of about 200 in many cases. Not that many survive today.

So Bellows is distributing and showing his lithographs from 1916 on across the country. He has a solo lithographic shows from 1917 up to his death in 1925. And so really the lithographic production is happening in tandem to the paintings. They both feed into each other to solidify his public reputation, which already by 1916 is big. He’s a famous artist early on. So really this comes later, it’s not a precise reproduction of any of the paintings but it’s pretty close. It’s really about this kind of parallel, a tandem form of image distribution.

CUNO: You said that he was exhibiting lithographs over the course of his career. Where were the lithographs or where were the prints exhibited and what was the market like for printing at this time.

GLISSON: So he’s exhibiting with print dealers in New York, Boston, and other cities also almost annually. And his prints sold for between $10 and $20 an impression which is more money than today but still relatively affordable and the prints were 1/100 of the cost of a painting. So he has steady sales of about $1,000 a year during this period, which is a pretty good amount of money to get just from the sales of the prints given that $1,000 went a lot farther in those days. So he sold prints widely and sold quite a bit of them during his career.

CUNO: Looking at this print you can see some precedence in Daumier, Degas, Manet. Maybe Stephanie you can tell us, how was he seeing these other prints if in fact there is these prints behind this one that we’re looking at?

SCHRADER: I think you’re absolutely right. So the artists that were being collected in the Metropolitan Museum of Art for the first time in 1916 were the same artists that American artists were interested in and looking at and sort of mining for inspiration. We know that the Met were collecting, not surprisingly, Daumier, Goya, Rembrandt, Hogarth. So early on subjects and artists that would relate to the things that you’re seeing in this exhibition. We know that Daumier was talked about to some great extent by Bellows’s mentor, Robert Henri, who taught at several New York City art schools, and he was always praising Daumier as someone that they should look at. In his lectures he refers to Daumier a lot, he refers to Rembrandt a lot, and he also refers to Goya.

And these artists were sold at the same print dealers in New York City so you could find them, John Sloan and other artists, in the exhibition.

CUNO: So we mentioned precedence in Daumier and Goya and Manet and Rembrandt, so those are precedents in both lithography as well as in etching. Was there a separate market for lithography and etching?

SCHRADER: The artists that were sort of specialists in etching prior to these artists, Whistler was one of them, and he was considered, you know, a fine artist, fine print maker. But they were also selling lithography and etchings at the same places.

So why don’t we go look at a lithograph that depicts where the works were sold?

So here you see the owner of the gallery standing with an art critic and artists all around in the room looking at works of art. So you see prints being examined in the back by the artist Peggy Bacon in the back, you see other artists looking at sculpture here, one kneeling down to examine something carefully which we can’t quite make out. So this is where art was sold and every single artist in this room exhibited here and sold their prints here. But they’re being sold with sculpture and paintings as well. So it wasn’t sort of segregated into you only can buy prints here and paintings there. It was more of a mix-up. And this was 1928.

CUNO: So there were a lot of books, evident there. So it’s also a bookshop.

SCHRADER: Yes, exactly. And you see them leafing through the catalog to see what the current prices are and what’s available.

CUNO: And this is made by Mabel Dwight? And you mentioned Peggy Bacon, another artist in the exhibition who is depicted in this print itself. Tell us about the world of women print makers.

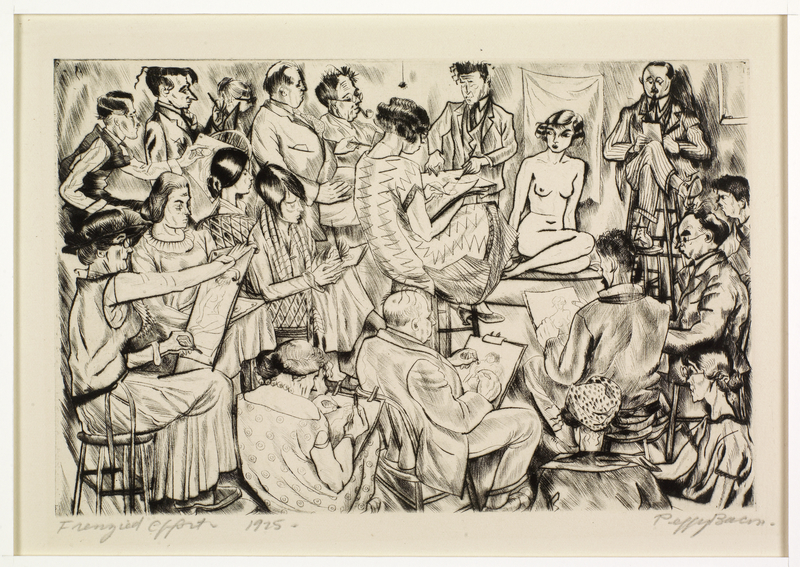

SCHRADER: OK, we might look at the Peggy Bacon drypoint Frenzied Effort that’s right next to it to give you a sense of women artists at this time. So this is a time when women were allowed to draw after the nude. This might seem like a completely anachronistic thing to say, but there were rules in the Victorian era America where you couldn’t draw from the nude and this was the time where women were permitted to draw from the nude and were gaining huge access to art production.

So this is a scene showing artists all feverishly drawing from the nude at the Whitney Studio Club which was started by Gloria Vanderbilt who was a woman herself. It was run by women and it allowed artists to come in, both men and women, to take classes, to exhibit. They also sold prints. Most of these prints were collected by Gloria Vanderbilt herself, later given to the Whitney Museum. So this is sort of the founding of American print culture right here.

And you see Peggy Bacon in the back with her glasses and her pointy nose. You see Mabel Dwight down here in the left-hand corner. And you can see that they’re not just men artists at work but women who are also drawing from the nude.

CUNO: And tell us about the context within which they made their prints, which is to say, were they painters as well? These women. There was no segregation between men and women.

SCHRADER: No there wasn’t. So their paintings aren’t as well known. It depends on which woman and what time, but they were all painters as well. I think they’re better print makers. They made many more prints than they did make paintings, but Peggy Bacon made pastels as well. And she was a self-taught artist. So when she joined the Arts Students League to study in 1917 there was no one teaching print making, so she taught herself. And the easiest print medium to teach yourself is drypoint where you are working right on the plate. And she worked with other women and saw a press in the corner of the room and they started making prints together.

CUNO: [Over Schrader] You say it’s the easiest way to make a print but it’s also the most unforgiving way to make a print. [SCHRADER: Yes, that’s true.] You can’t go back over something.

SCHRADER: No, you can’t go back but she, whereas Mabel Dwight couldn’t stand working in etchings. She thought it was too complicated and you like needed to be a chemist and alchemist to make an etching, so she preferred lithography and worked with print makers, Peggy Bacon made them herself.

CUNO: James, tell us about the training of these artists, these women artists in particular.

GLISSON: So the quantity of women who were art students starting in the 1860’s and 1870’s in the United States is pretty staggering if you look back on it. They almost never had the same kind of career trajectory as male artists but women were in art schools. They first studied in the 1880’s with say William Merritt Chase, later with Robert Henri, and there’s legions of women who are studying and working, whether that be at the Art Students League or at Chase’s school which later became Parsons.

So the training is roughly the same but, as we know, and Linda Nochlin taught us all a long time ago, the arc of a career is quite different for women who are artists. And up until relatively recently, the last generation or two of art history, many of these artists just haven’t received their due. So there’s work to be done in terms of scholarship to revive these careers and hopefully this show will get somebody excited and pick up the baton.

SCHRADER: Most of these women were married to artists and they subsequently divorced those artists and really found their way after they got divorced because they were always in the shadow of their artistic husbands.

And in the case of Mabel Dwight, she got married and for ten years she didn’t produce anything. Once she got divorced at the age of 50, she went to Paris, she learned lithography in Paris, she came back. At 52, she started making lithographs. And she really came into her own much later in life after she’d gotten rid of her husband. And she so despised him that she changed her name. So her name was Mabel Williamson but she became Mabel Dwight. She just invented her own identity. [Cuno laughs.] So it really speaks to this bohemian culture where these women, where they navigated, but it was still problematic for them to figure it out in relationship to their spouses.

CUNO: So, well, let’s go look at the Fourth of July. So we see a gathering of people sitting on a lawn in an outdoor setting with the fireworks breaking over their faces and their faces being illuminated by the light of the fireworks. What was the source of this painting if there was one behind it? In the 19th Century, lithography in particular, was associated with print publications and magazines and various things, even in the United States with things like Winslow Homer and Harper’s Bazaar and so forth. Was it also true in this case? Did they make prints for magazines?

SCHRADER: Yes, so I can answer that with great confidence that all of the artists in this exhibition were making illustrations for magazines. Vanity Fair, the New Yorker, they were supplementing their incomes by their commercial production of illustrations. Peggy Bacon herself wrote 19 children’s books that were illustrated.

Kira Markham is different in some ways in the fact that she was an actress and she was mostly fascinated with the light and the way dramatic light tells stories so she connected that back…

CUNO: As it would on the stage.

SCHRADER: Yes, exactly. So she was this art director in Hollywood, so she had a different trajectory than most. As far as I know, she didn’t make illustrations for magazines like Peggy Bacon and Mabel Dwight did, George Bellows, John Sloan, Edward Hopper, Martin Lewis. They all made for magazines.

But Kira Markham’s interests really came through the acting side. She, throughout her entire career, was performing even in Provincetown or in Los Angeles or in Chicago. She went to the Art Institute of Chicago and she was a painter but it was the light effects that really brought her to lithography more than anything else.

CUNO: We see that in almost every one of these prints. The stark contrast of light and dark. What about the city as a backdrop in a number of the prints in this exhibition.

GLISSON: I think the city was a marker or an index of contemporaneity. If you wanted to do a subject that felt fresh and vibrant and utterly of the moment, it was very likely to be an urban subject. And there was really no city in the world that was more or perceived to be more vibrant, more futuristic, more somewhat utopian and somewhat dystopian than New York. So New York has this really outsized role in early 20th Century imaginary, not just nationally but globally.

And I think that’s reflected in this exhibition. I think even if these artists had been in other cities, they probably would have done some pictures of New York. Its skyscrapers, its suspension bridges, the quantity of people moving through the streets, these were all markers of modernity and life as it was at this moment.

CUNO: So we were talking about the city as a backdrop for the prints in the exhibition, the subject matter of the prints of the exhibition, but they are made by artists I’ve never frankly heard of, Martin Lewis for one Ellison Hoover for another, Gerald Gearlings for a third. What was the range of their careers, the arc of their careers, that could help us understand the role they played in American art at that time?

GLISSON: So I can speak about Hoover and Gearlings. There’s very little information on Hoover at all. The image we have in this show is his, kind of, his iconic print, Manhattan Midnight.

Gearlings had a more complicated career and shortly after the Depression began, quit with printing entirely because he could not make a living, and went on to publish books on the history of decorative art and worked as a designer and interior designer. And had a very different kind of career trajectory.

Martin Lewis I’m going to have to pass over to Stephanie. But he is Australian, came to the United States and has the very interesting distinction of having taught Edward Hopper how to etch in 1915.

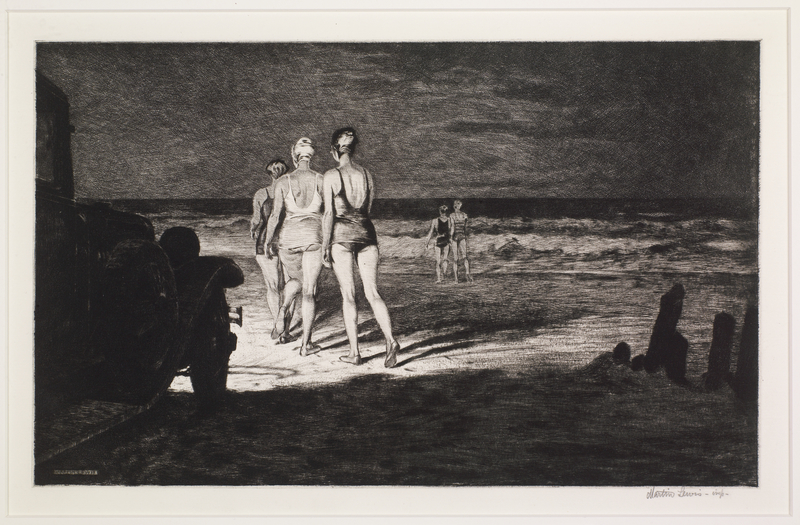

SCHRADER: So Martin Lewis is I think one of my favorites in the exhibition. He’s only a print maker, so he doesn’t make paintings like Bellows does and Hopper. He is solely focused on print making and he comes to New York as an illustrator and develops his specialty in print making. And he travels, so he goes to Japan and lives there for a while and is very interested in Japanese wood blocks so his whole career has been thinking carefully about illustration prints and how you can create these incredible effects with etching, with using sand on the etching plates to create this amazing atmosphere.

And you see an example of his work here Down to the Sea at Night, which shows five women going to swim at the seaside at night. And they’re being illuminated in this incredibly beautiful, atmospheric way by a car that has been driven onto the beach to allow them to see what they’re doing. And you see them sort of lurching their way down to the water as their legs are sort of stiff. They seem like they’re in a, some sort of evening ritual. It’s not this careful fluid movement. It’s very awkward and stiff. And the awkwardness is enhanced by the fact that their bathing suits are slowly creeping up their behinds. It’s not a, you know, scene of gods and goddesses and part of some revelry here.

And he loves these nighttime effects. Every single scene I think I can think of by him is either night or it’s a weather condition. So you see him showing rain or snow. He’s absolutely obsessed with getting just the right atmosphere and the right light and cropping his composition, so you have these very enigmatic ambiguous scenes of city life.

CUNO: It’s peculiar that you have an outdoor scene, a beach scene, all made in black and white, but then you see that all the prints in the exhibition are black and white. Were there color prints made at the time?

GLISSON: Absolutely. Bertha Lum, for instance, is making very beautiful color prints at this moment, and others. We early on decided to focus on black and white and our corpus of artists so to speak, worked almost exclusively in black and white. And certainly, particularly with lithograph, but with also some other techniques that are used, you can get a wonderful rich black with printing techniques. And there are many images in the show in which images seem to emerge from darkness into light. And that, to me, kind of plays with the whole true grit theme and all sorts of great somewhat ambiguous and somewhat open-ended but nonetheless resonant ways.

CUNO: I raised the question of the outdoor scenes because there’s outdoor scenes everywhere of people in parks and people on the street, but also there is the city itself as a backdrop in many of these prints. The architecture. And Martin Lewis being one example of someone who made such print.

GLISSON: So we’re looking at Martin Lewis’ Glow of the City from 1929 which is a dry point. And there is a woman dressed in the kind of low waisted style of the 1920’s. She’s standing on a fire escape and she’s looking across the back lot towards the backs of tenements in the distance into the Chanin Building, an art deco skyscraper that was on the west side of Manhattan at the time. It’s a kind of humid or foggy or cloudy night, and the lights of the Chanin Building merge with the atmosphere in this wonderful effect, and she’s staring on.

And this image for me is emblematic of how New York in particular, then and now, and Los Angeles then and now, was a place of promise for people. It’s where people came to realize romantic aspirations, professional aspirations, just sort of leave maybe a small town or midwestern city and realize their dreams and goals. And I think in this case the skyscraper lit at night symbolizes this for this young woman alone on a fire escape, probably living in Hell’s Kitchen which was then not such a great part of town, but she’s moved to New York and she’s trying to make something of herself.

CUNO: What about the Edward Hopper next to it too? Here the city plays a different role as a kind of not backdrop but an active participant in the making of the image.

GLISSON: Well I certainly wouldn’t call this hopeful and aspirational. We’re looking at Night Shadows, Edward Hopper’s etching of 1921. There is a man walking alone at night. He’s being viewed from above, it might be from the tracks of an El train, it might be out the window of an apartment building and there’s peculiar shadows that are cast all over the place. And there’s a sense of him being impinged or kind of held in by the buildings and structures around him. I like to think of him as almost walking through the light as if he were walking up a stream of water. You have this sense of resistance.

Here the city is a character in the drama that’s unfolding before us, and there’s this sense perhaps, there’s, maybe there’s people behind the windows or maybe it’s us who are looking down on him, but he’s not alone. And while it’s not exactly scary, you don’t have a sense that it’s placid, peaceful, reflective isolation. You have the sense, that’s so typical of Hopper, of a human being alone in an urban setting trying to wind his way through and wind his way upstream so to speak in this very intense nighttime light, with these tentacle light shadows that go all over the place.

CUNO: Stephanie, when you look at these prints, the dramatic ones of Edward Hopper, Martin Lewis for example, one can’t but think about films, black and white films at the time. What was the relationship between them, if there was one, or was it just generally the aesthetic of the printmaker?

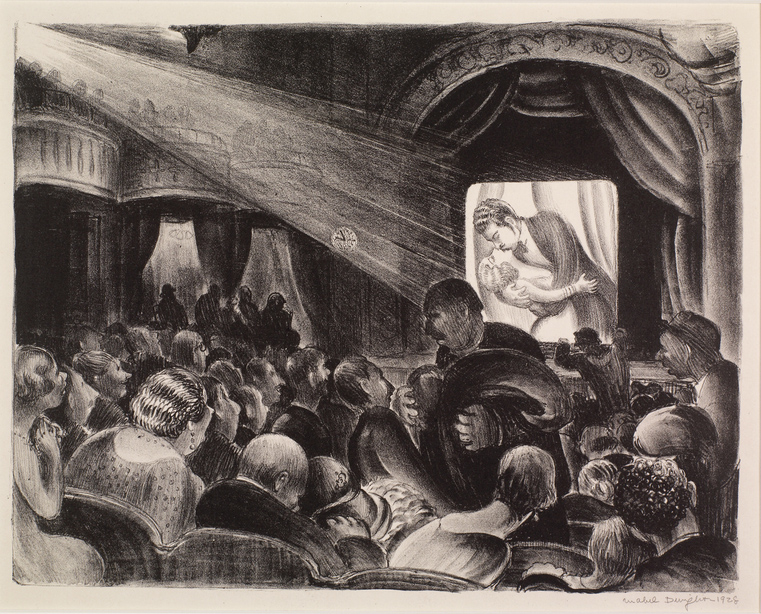

SCHRADER: Well let’s look over here actually the films that are being featured by these artists. So as you are right to point out, this is the time where people are enjoying going to the movies. I mean we still do that today. But back then, it’s when movies were moving from silent films to speakies, so they were talking. And you see two representations here, one by Mabel Dwight, another one by Armin Landeck, celebrating the film industry. And those kind of dramatic romances that happened in those movies at the time in the 20’s are definitely something that artists have completely immersed themselves in and thought about. Their dramatic use of light that you see Mabel Dwight picking up from the projector showing this film, and all the busyness and the hustle and bustle that happens within these movie theaters.

Because movies at this time, as James talks about in his essay for the exhibition, were shown all the time. They weren’t like set times, so people would come and go. They didn’t necessarily know what they were going to see when they got there, what part of the narrative they were going to be shown, so they would come in and leave when they had seen the film from its entirety. They didn’t need to see it from beginning to end. Sometimes they’d see it in the middle.

They were not quiet places where people silenced their cell phones the way they do now. They were busy and boisterous and people were eating and yelling and shouting and crying and, in this case, the Mabel Dwight version, the women were responding like overwhelmingly to the romance. You see them clasping their hands like “oh my gosh, he’s so handsome.” Or trying to look around the figures that are moving while the men are sleeping or disgusted by the romance.

CUNO: But there’s sometimes what seems like direct quotation from film or effects of film like a Fritz Lange, they were looking at Armin Landeck’s The Cat’s Paw or the Edward Hopper that we have just been talking about, the sense that the city has an active role to play not just setting a dramatic backdrop for action, but actually being active. And just here across the way we’ve got the city as the subject of it, Ellison Hoover’s Manhattan Midnight, for example. And next to it over here Wall Street by Arnold Ronnebeck. Tell us about that sense about where the city is becoming itself an actor in the prints and the films.

GLISSON: Well I think certainly the comparison with Fritz Lange and Metropolis or The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari really works with the Ronnebeck. But I think for both these artists and for film makers in the period, they understood the value of sets and environment and how that can immediately set the stage so to speak, and convey the alienation of the city, the threatening qualities of the city, certainly with the Ronnebeck.

So with Ronnebeck, again a very Fritz Lange German expressionist kind of way, buildings are leaning in. This is Lower Manhattan. The streets in Lower Manhattan are very narrow. In the distance you can see Trinity Church which is still present. It’s an Episcopal church, but it’s this little tiny spike. It looks a little malicious there in the distance. But the buildings lean in and it’s a sense as if they may not quite fall on top of you but they’ve blocked out the sky itself.

So this lithograph, it’s called Wall Street, it’s from 1925, gives a pretty negative and threatening image or a picture of Wall Street and it’s the financial center of New York City. So in the same way that with a Fritz Lange you maybe immediately know it’s a horror story, or that the movie’s not going to turn out very well, from the sets, say in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, with Arnold Ronnebeck, without Ronnebeck being polemical in any obvious way, we know exactly where he stands on his experience of New York and perhaps his views on Wall Street and the American financial system at that moment.

CUNO: Where was Ronnebeck from?

GLISSON: He was German and he’s most well-known for his friendship with Marsden Hartley, so they’re very connected in the early teens. And he was in the Gertrude Stein/Alice B. Toklas circle. In the early ’20’s, he came to the United States because of course the economic situation in German is terrible, and settled in Denver and did a lot of work I believe with the Denver Art Museum.

CUNO: I asked that question about the presence of foreign artists, non-American artists, in the exhibition because there is one by an artist, again an artist I’ve never heard of but I was attracted by the image, and his name is Miguel Covarrubias. Tell us about his work.

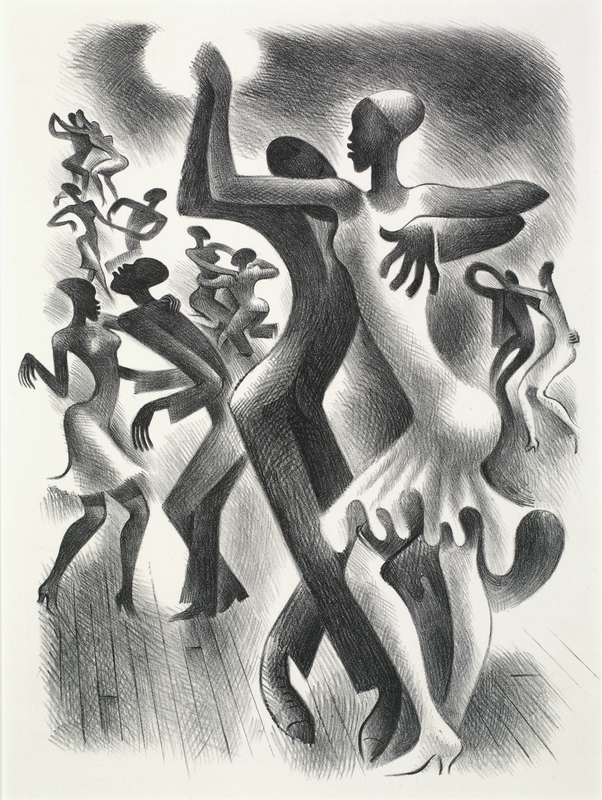

SCHRADER: Miguel Covarrubias was Mexican born and he came to the United States on a grant from the Mexican government when he was 19 years old. He was very well educated, he was an artist but he also trained as an anthropologist, and he quickly fell into the poetry and literary scene and was almost instantly making illustrations for Vanity Fair and for the New Yorker. He was a caricaturist primarily, and he really was able to sort of portray anybody who was anybody in New York City at the time, like almost immediately once he came to America.

And what you’re seeing him depict here is the Lindy Hop. This is a lithograph from 1936 in which you see him combining his interest in caricature and also his interest in ethnography, because he’s showing you a ballroom in Harlem, called the Savoy Ballroom, where they invented this dance. And it is a combination of ballroom dancing and West African dance traditions. And it was this very vibrant active dance where figures swirled throughout this dance room. And you see him representing several different couples dancing.

He was obsessed with Harlem, he was absolutely at this club almost every night looking at the ways people interacted. And I should say that this was one of the only places in the age of segregation where different races could mix.

CUNO: So it’s made in 1936 which of course brings to mind the Great Depression. [Schrader: Yes.] What was the role of the government in supporting print making at the time?

SCHRADER: Right. So not all, but many of these artists, especially the women, had the great fortune of getting government funding from the WPA. So one of the things that the government figured out early on was that print making was an affordable medium. It could circulate ideas about America and American culture in a way that was mass produced and easily distributed. So they would hire artists, and 41% of them were women, to make prints. Mabel Dwight had the benefit of getting $33 a month from the American government. She had to make three prints a month depicting different scenes in American life.

It was a time where they really thought art was important and it would matter and make a difference to people. They did not think of it as something elevated and elitist, but they really thought it was art for the people by the people, and this was a way for artists to be paid and to make a living even through the most difficult of economic times. And most of these artists survived that through the WPA and through government funding.

CUNO: I think every print that we’re looking at situates itself at least in the imagination, as being in New York City. But was print making as vital across the country as it was in New York City or was New York City special?

SCHRADER: Well New York City was special but why don’t we go look at the Millard Sheets because he was a Los Angeles artist that was very important for printmaking here.

GLISSON: So we’re looking at Family Flats by Millard Sheets from about 1933. It’s a lithograph and it’s an image of Bunker Hill in downtown Los Angeles, but long before the Bunker Hill that we’ve all come to know with Disney Hall and the Broad and skyscrapers. It’s the Bunker Hill of tenements, of wooden buildings, and of working-class housing.

Millard Sheets was born in the Los Angeles area out by Pomona. He studied at Chouinard.

CUNO An art school here in Los Angeles?

GLISSON: An art school here in Los Angeles. And relatively early shot to fame. And in 1929 he sold some works and could finance a trip to Europe. He goes to Paris and he works and studies for a bit at a lithography school in Paris. He then comes back to the United States, quickly has a very successful career exhibiting his paintings nationally, beginning to do the mural commissions, both painted and mosaic, for which he would become well known by the 1960’s.

Family Flats is from ’33, it’s relatively early, and it’s him probably applying many of the things he learned in Paris. It’s closely related to two paintings, one at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the other one, Tenement Flats, that’s at Los Angeles County. And these two paintings are probably Sheets’s most famous and most iconic. Both of Bunker Hill and both intent on capturing this vertiginous, twisted space with these balconies as you’re looking up a hill. These very steep hills. So an interest in twisting space.

Now the title, there’s this alternative title called The Supreme Court in Session. And it is a kind of ironic, sardonic, probably mocking and a bit condescending, on the group of women who are out watching children and tending to children and with their arms akimbo seeming to pass judgment on what’s going on around them. So it is much like the other artists in this show who are interested in New York City tenement life and the life of immigrants in the Lower East Side, Millard Sheets is looking at the Bunker Hill area as a kind of parallel to the Lower East Side and looking at working class and presumably working class immigrant life in Los Angeles.

CUNO: It has a suggestion of a stage set to it, which reminds me again of this role of the film industry, that’s shaping the aesthetic of painting and print making at the time. Was there a lively market for and community of printmakers in Los Angeles at this time, 1930s?

GLISSON: It’s not large. There’s Henrietta Shore who’s making some prints. It’s converged around this lithography shop run by a man named Kistler. And not as large as New York but it’s still definitely present and there are lots of interesting lithographs from the 1930s made here in Los Angeles. But the community just isn’t as large as New York.

CUNO: Well the exhibition introduces us to a great number of artists, as I said earlier in the podcast, that we’ve not heard before or seen before.

Stephanie, the last essay in the exhibition catalog begins with a quote from the painter/printmaker, Robert Henri. He says “a work of art is the trace of a magnificent struggle.” How does this apply to printmaking, especially, and especially to making of prints in this exhibition?

SCHRADER: So we’re going to end here by looking at a print here by Fritz Eichenberg. He’s depicting a subway, and I think this sort of speaks to these notions of magnificent struggle for this exhibition. Most of the scenes you see depicted here are of the city, city life, and they’re depicting the diverse communities that live in these cities. They’re depicting a huge number of immigrants. And a lot of these artists were immigrants themselves.

So Fritz Eichenberg, again, is an immigrant coming from Germany, fleeing Hitler and coming to New York City to find a world that is completely and utterly different than the one he came from. But at the same time it’s different, and it’s hard, and he’s showing you a subway scene with people exhausted after working. He really believed the subway, and we have a quote here from him, “composed of all the voices of the earth.”

So in this melting pot of New York City, he found everybody and every aspect of the world, both the good side and the bad side. But he still thought of it as a celebration in some way. It was still a magnificent backdrop for him, the subway, to show people who are immersed here, you know, surrounded by advertisements as they move through the city at night, full of people, you know, full of people sleeping and exhaustion and hunched over after a long day. But he’s celebrating this and finding it worthy of depiction.

And we know specifically from the inscriptions where it’s going, it’s going to Brooklyn. We know how people are coming in and out of the city at this time. And I do think that sense of struggle in some ways is implied by both the people who live there, the artists that are representing them, and actually seeing their own lives in the lives of other people. So they’re taking to the streets, they’re not just working for wealthy patrons and thinking about elevated topics, they’re looking at the now, the mundane, the uninteresting, and making it memorable and circulating for everyone to enjoy.

CUNO: Well you’ve certainly by this exhibition introduced us to artists again that I’ve never known before and whose work is not known and whose work is extraordinary and you’ve chosen exquisite impressions of the prints, where the blacks and whites are as clear and bright as can be. So thank you very much for this, James and Stephanie. It’s a fantastic exhibition and we’re thrilled to have it at the Getty.

SCHRADER: Thank you.

GLISSON: Thank you.

CUNO: Our theme music comes from “The Dharma at Big Sur,” composed by John Adams for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. It is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts or Google Play Music. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts. Thanks for listening.

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

STEPHANIE SCHRADER: They’re taking to the streets, they’re not just working for wealthy patrons...

Music Credits

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.