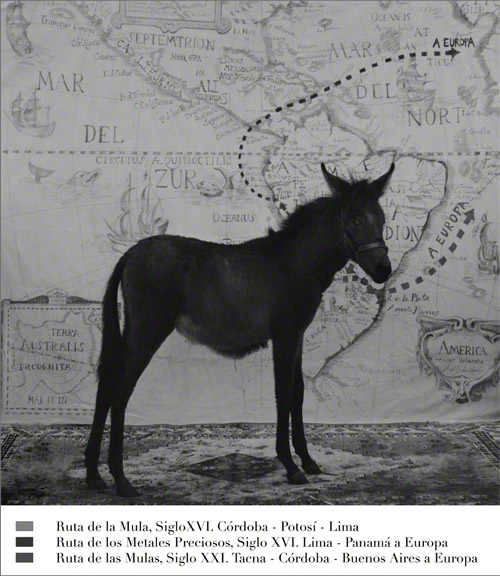

Anthropología de la Mula/Anthropology of the Mule, Adriana Bustos, 2007. Photograph, 146 x 125 cm, edition 5 + 1AP. Courtesy of the artist and Ignacio Liprandi Arte Contemporáneo

Is there any consensus about the definition and field of “Latin American art”? This question was the subject of discussion by a group of international art historians and curators at a recent two-part, two-continent symposium, Between Theory and Practice: Rethinking Latin American Art in the 21st Century. The event began in L.A. in March and concluded in Lima this November. Videos of the symposium presentations are available online here.

While many museums and university art history departments use the term “Latin American art” to refer to art from the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking region that extends from Mexico and the Caribbean down to the southern reaches of Chile and Argentina, this group’s investigation of the term produced more questions than answers, particularly because of the area’s colonial past.

I spoke with one of the symposium’s organizers, Cecilia Fajardo-Hill, chief curator at the Museum of Latin American Art (MOLAA) in Long Beach, about the discussion that emerged.

Although the recent seminar took place far from Los Angeles, in Peru, this is a project that got started at the Getty?

Yes, the symposium took place in two installments. The first was at the Getty Center and MOLAAin March of this year. The second installment occurred in November at the Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) in Lima, Peru. MOLAA initiated the project in collaboration with the Getty Research Institute and MALI, and the Getty Foundation provided a grant to support international scholars working in the field of Latin American art to come together for these two seminars.

I understand that the very term of this area of study, Latin American art, is controversial for those working in the field. Maybe you could frame the debate for us?

The generic term “Latin American art”—as well as “Latin American culture”—continues to be extremely problematic, because of its nationalistic undertones and its origins as an imposed, stereotypical, unifying idea. Studies relating to Latin American art are taking place all over the globe today, from New York to Peru. Regardless of their physical location, scholars are working on related issues.

So how could there be one category for such a large region or even one type of art that we could point to and say, now that is Latin American art?

Yes, any attempt to create an artificial order in the field would be forced and unproductive. It was clear at the symposium that important practices in contemporary art are being developed within Latin America, the United States, and Europe around shared concerns. These scholars and curators are bringing multiple perspectives to the same subject matter, thus creating a truly complex, rich, and diverse field.

So was the group able to reach a consensus on what constitutes Latin American art and whether the term should continue to be used?

The museum, university, and independent scholars who gathered for the symposium couldn’t agree upon any single model for a shared practice in Latin America, as this would require the establishment of a defining and simplifying canon in the field.

During the symposium, the most widespread rejection of the term Latin American art was based on its usage in the contemporary and modern art market, which has a limiting effect on the public’s perception of the art produced in the region. Nevertheless, some of the scholars argued that they continue to find it useful and necessary as a term, particularly because it provides a framework within universities and museums to create specialized departments for research, study, collecting, curatorial practice, and publications.

So even if the term is problematic, the stakes are high if we stop using “Latin American art” as a category?

If the term disappears, a museum may never include Latin American artists in its collections or exhibition programs. The general category of being “Latin American” is inescapable, a sort of inevitable political condition to bear.

Everyone could agree that conditions of scholarly production in Latin America are difficult. There are limited resources, information is widely dispersed and difficult to access, and the exchange among art historians and curators within Latin America is insufficient.

This is precisely the problem that the Getty Foundation is addressing with its Connecting Art Histories initiative, the program that MOLAA is participating in with this symposium.

Yes, and we feel that the creation of networks of production and interpretation of knowledge in the field, and sharing and distribution within Latin America, is of primary importance. Therefore the fact that the second part of the symposium took place in Lima and included scholars from the United States and Europe, as well as nearby countries, was an important symbol of the feasibility and productivity of this type of exchange.

Text of this post © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved.

Comments on this post are now closed.