Four terracotta mourning women, 300–275 B.C., Greek. Terracotta with polychromy, 37 7/8 × 9 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.AD.76.1–4 (left to right)

For the first time, four terracotta statues of mourning women that have long been in storage have gone on display, and are on view at the Getty Villa through April 1. Bringing these figures—made in the town of Canosa in southern Italy in the third century B.C.—out of storage has given Getty curators and conservators an exciting opportunity to study how they were made and to learn more about South Italian funerary art and practices.

Statue of a Mourning Woman (detail), 300–275 B.C., Greek. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.AD.76.4

The four figures of young women form a striking and, perhaps, unsettling quartet. Half life-sized, with coordinated outfits, matching hairstyles, and identical poses, they are identified as mourners by their grief-stricken faces and hands raised in prayer.

These “mourning women” statues represent a type of funerary sculpture that is specific to the town of Canosa, located in the Daunian region of southern Italy, and was made during the late fourth and early third centuries B.C. (1). They are unusual for their size (they are much larger than most terracotta figures from Greece) and are comparatively rare. Only 48 are known to exist, of which just nine are in museum collections in the United States (in addition to these four, there is one more in the Getty collection, one in the San Antonio Museum of Art, and three in the Worcester Art Museum).

With so few examples in North American museums, the team here at the Getty Villa was excited by what we might learn about this sculpture group. How were these mourning women made? How do they compare to the other examples of mourners in international collections, like those at the Worcester Art Museum? And what can these mourning women tell us about ancient funerary practices? Conducting a technical analysis of the sculptures revealed some answers.

The Mourning Women

All 48 mourning women can be grouped according to different combinations of dress, hairstyle, gesture, and facial expression. We also know from excavation records that they would have been placed inside aristocratic tombs in matching sets of two, four, six, or eight. Inside the tomb, the figures were arranged around the funeral couch, where they acted as permanent attendants for the deceased, providing continuous prayer and lamentation as a way of ensuring safe passage for the soul into the afterlife.

Knowing this has allowed scholars to propose that statues now dispersed in different museum collections were originally buried together (2). The statues may also indicate that real young women had a special role as mourners in local funeral processions (3).

Given their limited production and localized use, it is likely that all 48 statues were made in the same workshop or closely related workshops. The differences in appearance probably demonstrate the work of individual craftsmen or the preferences of the people who commissioned them, who perhaps selected from a repertoire of standard heads, gestures, and bodies (4).

The Getty examples share the same pose, hairstyle, and face type as other mourning women, but wear their cloaks in a way that is unique amongst the group as a whole, draped like a shawl with one corner hanging over the figure’s left shoulder onto her chest. Was the detail a special request from the buyer, or the hallmark of a particular artist? (5)

While that question can’t be answered solely with a technical analysis of the sculptures, a close investigation of the materials and techniques used to make them did shed light on how the Getty’s mourning women were made.

Analysis of the Sculptures

Left: Close-up of X-radiograph of another mourning woman (85.AD.76.4) showing how the neck was inserted into the torso. Photo: Jeffrey Maish. Right: Examining an X-radiograph of one of the mourning women (85.AD.76.2) in the Getty Museum conservation labs. Photo: Marie Svoboda.

We started by taking an X-radiograph of each mourner. This showed that, like the Worcester examples, the artist built the basic conical shape of each figure working by hand horizontally from the bottom up (6). Openings were left at the shoulders and collarbone to insert the arms and head, which were made separately. Tiny, irregular voids or air pockets are clearly visible on the scans and suggest that the shape was built using small pieces of clay rather than larger slabs, and were possibly pressed against a supporting structure.

This technique, which is different to how Greek terracotta figures were generally made and probably represents a local craft tradition, helped the craftsmen to create such large figures. Examining the interior of the body, we could see where the clay had been shaped and smoothed by hand—we even found finger marks! We could also see that the undulations in the drapery of the skirt where the bent leg appeared to extend through the folds had been made by pushing the clay out from the inside, and that extra rolls of clay had been added on the outside of the figure and then shaped with tools to form folds in the clothing.

Holes that appear in the hem of each skirt (visible in the image at the top of this post) were probably used to secure the statues in the tomb, perhaps to a base (7). This theory is supported by an observation we made while preparing them for mounting at that Villa: each figure leans in a different direction and cannot stand easily on its own.

Left: Rolls of clay added to the exterior of the same mourning woman to form folds in drapery. Photo: Ruth Allen. Right: Interior view of one of the mourning women (85.AD.76.2) showing finger and tool marks. Photo: Marie Svoboda.

While the bodies were modeled by hand, the heads were made with a bivalve mold. We confirmed that the maker used this technique by taking a stereo pair radiograph of the head of one of the figures (85.AD.76.4), which revealed a seam beneath the hair where the two halves had been joined.

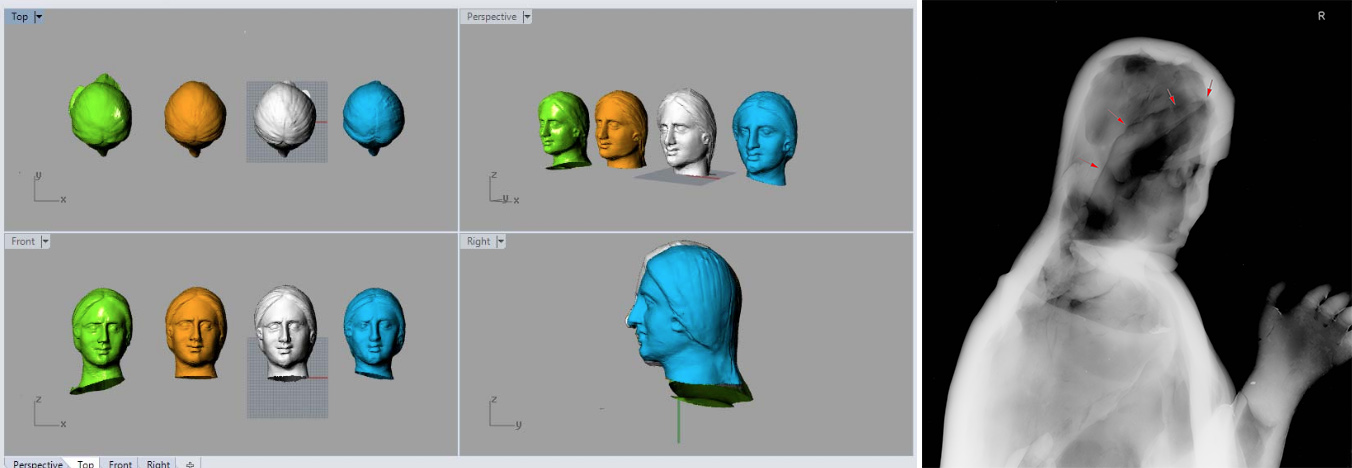

Left: 3D scans of all four heads. Image: Richard Hards. Right: Stereo pair radiograph of the head of the last mourning woman pictured at the top of this post (85.AD.76.4), showing where two halves of the head have been joined together. Image: Jeffrey Maish.

We also took 3D scans of all four heads that, when placed side by side, show they were made using the same mold. Violaine Jeammet, a senior curator at the Musée du Louvre, has determined that only five molds were used to create the heads of all of the 48 existing statues (8).

A Single Craftsman?

While the Getty’s mourning women have much in common with other examples, some of the ways in which they were made distinguish them and, like their unusual dress, may also be the signature of a particular craftsman.

Left: Back view of British Museum 1873,0820.555 showing rectangular vent hole. Photo: Ruth Allen. Right: Back view of 85.AD.76.1. Photo: J. Paul Getty Museum.

Most mourners, for example, have a large rectangular opening at their back, which allowed the artist to secure the head and arms from the inside; it also helped the clay to dry. The Getty pieces do not have this feature and seem instead to have been made in two halves. Analysis made visible a horizontal join line in the interior of one mourning woman (.2) and corresponds on the outside to the lower edge of the cloak, which helped conceal the seam. The head and arms would have been first attached to the torso from the inside, and the upper half then joined to the legs.

This method of assembly ensured a more visually appealing finish, but it also would have presented a challenge to the artist. The Getty figures are two mirrored pairs: two bend their right leg and hold their left hand slightly higher than their right, and two bend their left leg and hold their right hand slightly higher than their left. Each inclines her head away from her bent leg. However, the costumes of all four drape identically over their torsos, which may have made it harder to attach the correct legs to the correct upper body during the manufacturing process.

Letters scratched onto the cloaks of figures85.AD.76.1–.4 (left to right)

We wondered if another unusual feature of the mourners offered a solution to that challenge.

As archaeologist Maria Lucia Ferruzza notes in her catalogue of the Getty’s collection of South Italian terracottas, each figure has a letter scratched onto the front of her cloak (85.AD.76.4 has two additional parallel lines). The Getty statues are the only known examples of mourning women with these markings, but we know such marks were used on contemporary Canosan pottery as a guide for assembly. For example, a decorative appliqué belonging to a terracotta pitcher found in a Canosan tomb is incised on the back with a letter that matches another on the body of the jug, indicating where it was to be positioned (9). The artist who made the Getty’s mourning women may have used the letters in a similar way: we noticed the marks were scratched on the same side as each figure’s bent leg, perhaps helping the craftsman match each torso to the correct legs by aligning the letter with the bent knee.

The Mourners in Ancient Context

Their finish was therefore important. Not only were they made to be seen in the round, but they were also brightly painted. Analyzing each mourner using a portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometer reveals they were covered with a white kaolin slip, after which red iron oxide was added to color the hair, lips and shoes. Madder lake, identified with ultraviolet light, was used for the vertical decorative stripes on each dress.

The application of paint enlivened the figures, making them more convincing stand-ins for real mourners. The surface of the clay was also burnished, and we can imagine how the statues must have glinted in the flickering candlelight of the tomb, giving the impression that they were swaying together in grief, watching over the deceased’s transition into the Underworld.

Left to right: UV light reveals traces of surviving pigment used to enliven the appearance of figures 85.AD.76.1–4. Images: Marie Svoboda

Studying the Getty’s mourning women has helped us understand how Canosan elites displayed their status and even their cultural identity through the objects they chose to be buried with. They also reveal ancient concerns about the afterlife, and demonstrate women’s important role as mourners.

Most excitingly, though, studying these figures has given us insight into Canosan workshop practices and brought us into almost literal contact with the hands of ancient artisans. They might look creepy, but they have lots to tell us. Meet them at the Getty Villa before they return to the “Underworld” on April 1.

_______

Notes

1. For cataloguing and discussion, see M. L. Ferruzza, Ancient Terracottas from South Italy and Sicily in the J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2016), nos. 38–41.

2. See V. Jeammet, “Quelques particularités de la production des pleureuses Canosines en terre cuite.” In Revue Archeologique 2 (2003), 225–292.

3. This is discussed in T. D’Angelo and M. Muratov, “Silent attendants. Terracotta statutes and death rituals in Canosa.” In M. Dillon, E. Eidinow, L. Maurizio (eds), Women’s Ritual Competence in the Greco-Roman Mediterranean. Routledge monographs in classical studies (London and New York: Routledge, 2016), 65–93.

5. Some red figure vases from Apulia, also in southern Italy, show women dressed similarly. Compare A. D. Trendall and A. Cambitoglou, The Red-Figured Vases of Apulia (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), vol. 2, 723–724 and 856–860.

6. For analysis of the Worcester mourning women, see S. D. Costello and P. Klausmeyer. “A reunited pair: the conservation, technical study, and ethical decisions involved in exhibiting two terracotta orante statues from Canosa.” In Studies in Conservation 59, no. 6 (2014), 377–390. For examples in Paris, see Jeammet 2003, 257–260.

7. These are found on the majority of examples, but with no regular number or position. Some scholars have suggested the holes were used to fix the terracottas to platforms that were carried as part of the funeral procession (e.g. D’Angelo and Muratov 2014, 82).

Should like to order a copy of the article.

See my contribution on the subject: “Orantes” canosines, in Genève et l’Italie, Mélanges publiés à l’occasion du 80e anniversaire de la Société genevoise d’étude italiennes, sous la direction d’Angela Kahn-Laginestra, Genève 1999, 43-65.

Intriguing conclusions that draw questions—as research usually does! While the question of whether the 48 women statures were made at the same or different workshops is relevant, the cautious conclusion that “…real young women had a special role as mourners in local funeral processions,” falls right into the humanistic understanding of ancient people’s beliefs and practices.