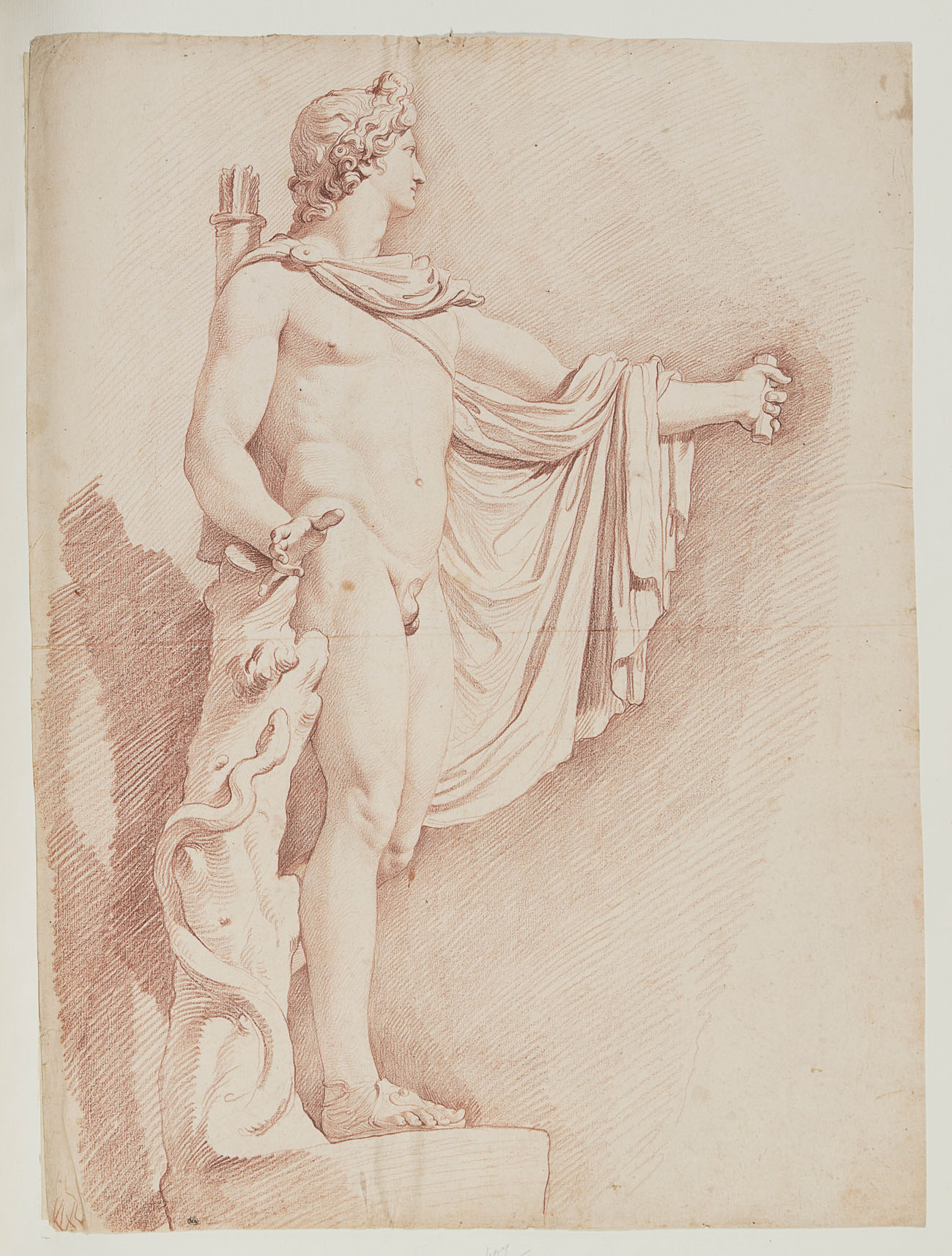

The Apollo Belvedere, 1726–32, Edme Bouchardon. Red chalk, 22 1/2 x 16 7/8 in. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts graphiques, INV. 23999. © Musée du Louvre, dist. RMN – Grand Palais / Laurent Chastel

The drawings exhibition The Sculptural Line was timed to coincide with Bouchardon: Royal Artist of the Enlightenment, a large international exhibition that has brought to life the work of one of the most accomplished sculptors of eighteenth-century France. Besides his activity as a sculptor, Bouchardon was also an incredibly prolific draftsman whose creative act often began on paper, working out ideas through meticulous drawings, mostly executed in red chalk. Like many artists of his time, Bouchardon visited Italy and spent time in Rome to learn and study the art of the past; there he drew after the antique and modern sculptures that abounded everywhere in the city.

In Rome, during the Renaissance, important statues from antiquity were rediscovered—literally unearthed from the soil of the city after having been buried in dirt and oblivion for centuries. Soon they became among the most celebrated examples of classical sculpture ever since. Their rediscovery was so sensational that artists flocked to Rome to see them. Parallel to these rediscoveries were those of antique texts by classical authors such as Cicero, Pliny, and Vitruvius, which profoundly influenced Renaissance artists. Through them, artists learned that classical sculpture was based on harmonic proportions that were the consequence of a precise, mathematical relation between the head, limbs, and body. This harmonious relation was seen to parallel the harmony on which the universe was established.

A Draftsman in the Capitoline Gallery, about 1765, Hubert Robert. Red chalk, 18 x 13 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007.12. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Drawing after sculpture, especially classical sculpture, became common practice starting in the Renaissance, as antique statues were perceived to be the embodiment of perfection and ideal beauty. In art academies, which flourished across Europe, artists were taught to admire and learn their perfect proportions and encouraged to exercise by copying them. Classical sculpture offered artists a repertory of poses and forms that could be models of inspiration for their own works.

Taddeo in the Belvedere Court in the Vatican Drawing the Laocoön, about 1595, Federico Zuccaro. Pen and brown ink, brush with brown wash, over black chalk and touches of red chalk, 6 7/8 x 16 3/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 99.GA.6.17. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

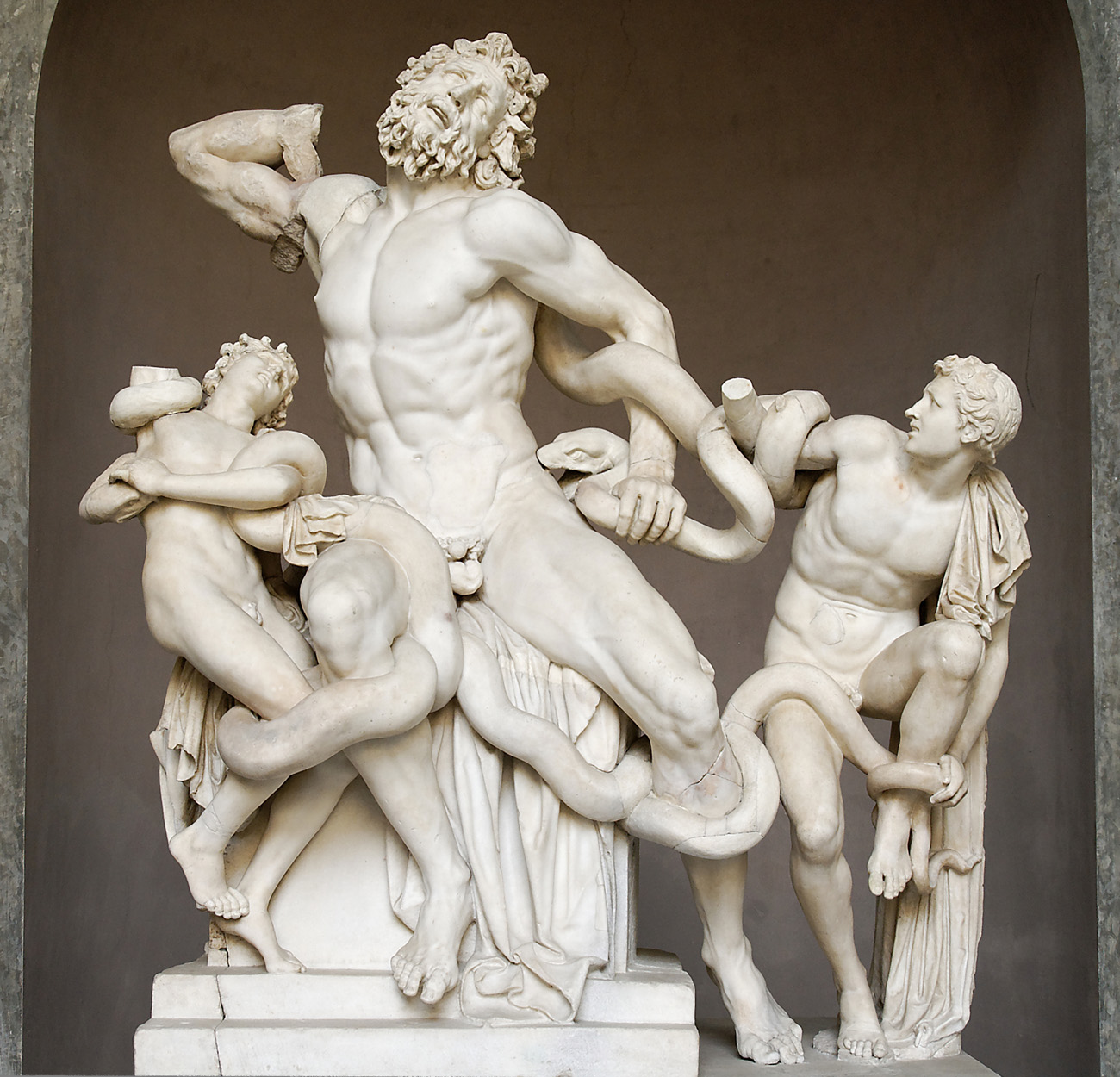

The most famous of all classical statues was, and probably still is, the Laocoön, which was dug out of the ground in a Roman vineyard on January 14, 1506. This was immediately recognized to be the famous marble group described by the Roman natural philosopher Pliny the Elder. The three complex figures represent the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons struggling against the lethal bites of serpents sent by the God Apollo to punish Laocoön for his disobedience.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, who was in Rome then, working for the pope, was immediately sent to see the new marvel on the recommendation of Pope Julius II, who was passionate about classical sculpture. The pope bought the marble group and placed it in the Vatican, in the Belvedere Courtyard, where artists and amateurs went to see it and study its daring composition. Full-size casts and smaller replicas were widely and rapidly produced for collectors as well as artist’s workshops, thus becoming a fundamental source of creativeness. Artists who could not make the journey to Rome could still study it after those replicas.

Laocoön and His Sons, Renaissance copy after a Hellenistic original from ca. 200 B.C. Sculpture: marble, 8ft. high. Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Laocoön, about 1720, Giovanni Battista Foggini. Bronze, 22 1/16 in. high. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.SB.413. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

The Venetian painter Jacopo Tintoretto, who never sculpted, owned many of these replicas, made in bronze, wax, and plaster. According to the biographer Carlo Ridolfi, Tintoretto spent a considerable sum on collecting casts of ancient and Renaissance marbles. Several of his graphic works attest to his practice of sketching after them. In the drawings illustrated below are two of these examples. The first is after the head of the Emperor Vitellius, a celebrated bust that in 1523 was sent from Rome to Venice by Cardinal Grimani, and was then displayed in the Ducal Palace, where artists could study and make plaster casts from it. The second is after a Renaissance sculpture representing an Atlas. The latter brilliantly shows a practice that seems to have been common in Tintoretto’s work. The artist would often draw at night, in the candlelight, moving a candle around the casts in order to explore the play of light and shadow on those forms. The stark contrast of black chalk with touches of white heightening creates a strong sculptural effect in all his drawings.

Study of a Bust of Vitellius, 1533–94, Jacopo Tintoretto. Charcoal, heightened with white, on blue paper, 30.4 x 20.7 cm. The British Museum, London, 1885,0509.1658. Image © Trustees of the British Museum, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license

Studies of a Statuette of Atlas, 1549, Jacopo Tintoretto. Black chalk heightened with white chalk, 10 x 15 7/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 89.GM.72. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

The Sculptural Line, on view until April 16, 2017, showcases drawings and sculptures from the late fifteenth through the twentieth centuries, with the aim to show that although drawing and sculpting may appear profoundly different, for artists the two disciplines were often intertwined.

Comments on this post are now closed.