Oscar Wilde once wrote that California is “very Italy, without the art.” As art historian Peter J. Holliday discovered in writing his new book American Arcadia: California and the Classical Tradition, ancient Greece and Rome are everywhere in our state. Consider place names like Pomona, Roman goddess of fruit, or Arcadia, verdant paradise of Virgil and Horace. Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom and war, presides over our state seal. Even our motto, “Eureka,” comes from ancient Greece—it’s mathematician Archimedes’ famous exclamation, “I’ve found it!”

And that’s not even to mention the many monuments—Hearst Castle, the Huntington, the Getty Villa, L.A. City Hall—that take inspiration directly from ancient Greek or Roman models. Holliday comes to speak at the Getty Villa on October 5 about the surprisingly prevalent classical influence in the Southland—that’s L.A. writ large, from San Simeon to San Diego. We asked him to fill in the blank on a few tidbits from his book, and his life as a historian and professor of classical art and archaeology.

Peter J. Holliday at the Getty Center. Photo: Marc Harnly. All rights reserved

Favorite discovery made while researching your book, American Arcadia: After giving public lectures related to the material in this book, people have frequently come up to me to share stories about their memories and experiences of the people and places I just discussed. It’s like a living oral history project, providing a font of information you would never find in books.

Holliday’s book American Arcadia explores California’s debt to the ancient world. (Oxford University Press, 2016).

Most memorable story revealed in the book: So many colorful characters make an appearance in the book; it’s hard to choose one! But I suppose most people might find the origins of Griffith Park surprising. In 1882 Griffith J. Griffith, a Welshman who made his fortune in mining, acquired about 4,000 acres of the old Rancho Los Feliz land grant. In 1903, while vacationing in Santa Monica, the supposed teetotaler shot his wife while he was in a drunken rage. The shot did not kill Christina, but it did leave her disfigured. In what was the first of Los Angeles’s numerous “trials of the century,” Christina was granted a divorce on the grounds of cruelty, the decree being made in the record time of four-and-a-half minutes. In 1904 Griffith was forced to sell more than 60 acres of his Los Feliz property for $36,000 to settle a lawsuit brought by his ex-wife. In December 1896 he donated 3,015 acres for a public park, calling it “a Christmas present” to the people of Los Angeles. That gift was simply part of a major public relations ploy.

Most fun I had while writing the book: For me the most enjoyable aspect of research is when I begin to make connections, to discover some totally insignificant details that have a tangential link to something else. For example, Billy Wilkerson, founder of the Hollywood Reporter and a notable figure on the Sunset Strip, originally began the Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas, until Bugsy Siegel “took over.” Wilkerson engaged George Russell of Russell and Samaniego, who had collaborated with Charles Selkirk on developing Sunset Plaza. Russell’s partner Eduardo Samaniego’s brother was an actor better known by his screen name, Ramon Novarro. Thus from the very beginning we find a series of unexpected links between Hollywood and Las Vegas.

Aimee Semple McPherson, February 14, 1927. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, npcc-16474.

Most delicious character—hero, scamp, or villain: Aimee Semple McPherson—Sister Aimee—covers all those bases, and more. She preached against the excesses of the Jazz Age, but every service was a spectacle performed for a congregation living in the entertainment capital of the world. Scandal continually shadowed her personal life, so she frequently based her sermons on her own trials and tribulations. She emphasized the love of God, and eschewed the fire and brimstone sermons popular with her peers.

She racially integrated her services, fostered ecumenical outreach and inclusion, fed thousands during the Depression, and worked tirelessly for the war effort during World War II. After relishing the fall of so many corrupt evangelists in our own day, it would be easy to mock her; but I come away much like Carey McWilliams did: admiring her for all the selfless work she accomplished.

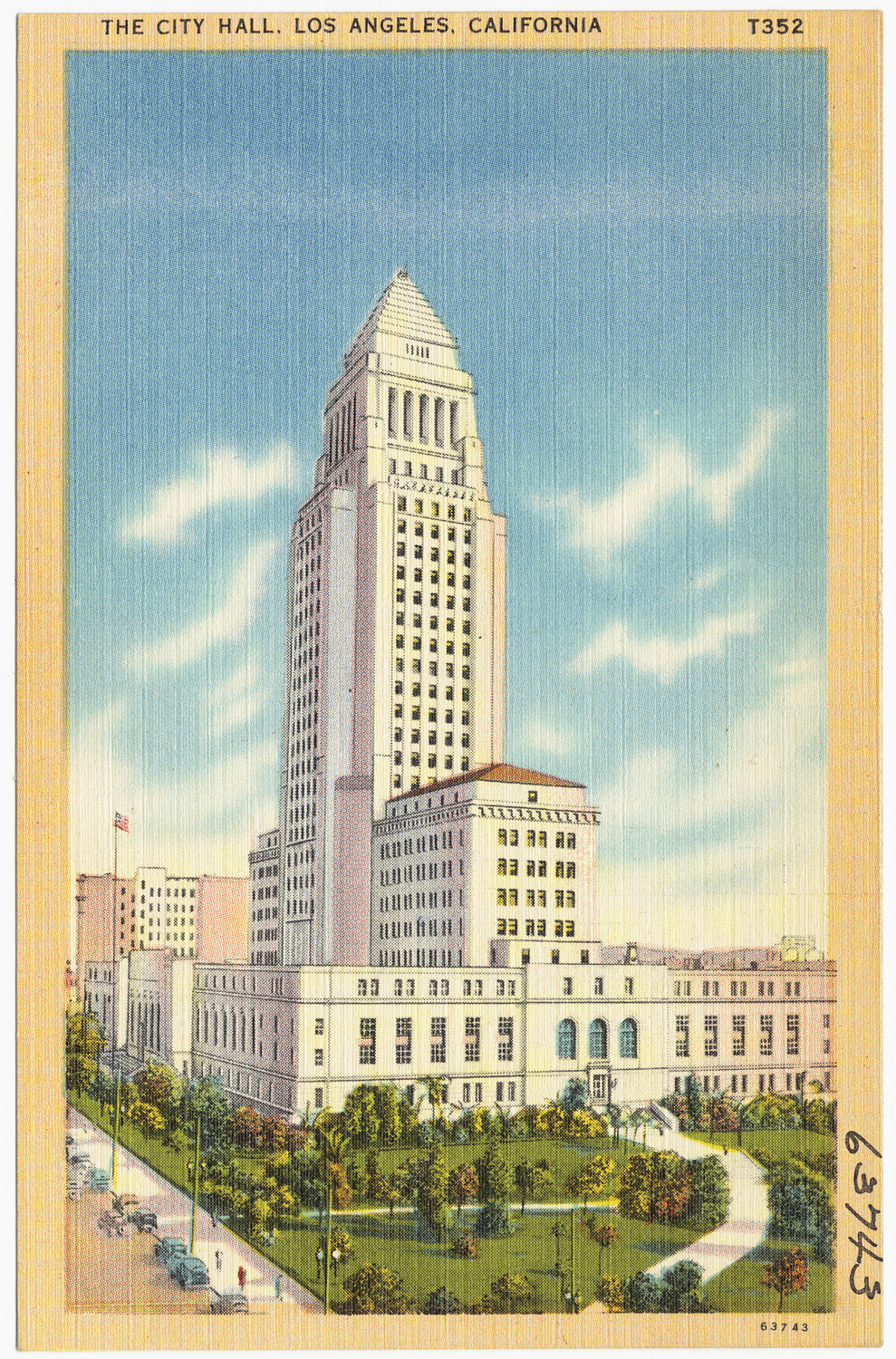

Most surprising adaptation of ancient Greece or Rome in California: The copy of the Mausoleum of Halikarnassos atop the Los Angeles City Hall. It was common practice to adapt versions of historical architecture to house the various machinery (water tower, elevator apparatus, and such) necessitated by the height of early skyscrapers. So few people recognize the Mausoleum as the source here until it is pointed out to them, and it draws attention to how many other examples of the creative use of antiquity we “see” every day but remain unaware of. It also underscores how tedious and boring the flat-topped towers of late 20th-century L.A. are.

Los Angeles City Hall, completed in 1928, is capped by a ziggurat-style structure inspired by the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus. Postcard dated 1930–45 from the Boston Public Library, Print Department, CC BY 2.0

Favorite classically influenced California building: There are so many classically influenced structures in California that I love, but if I had to choose a favorite it might be the house William Tanner designed in Los Feliz for film director Dorothy Arzner and choreographer Marion Morgan, with landscaping designed by Florence Yoch. It’s not an attempt at recreating an actual structure like the Getty Villa, and it’s much more modest than the fantastic Hearst Castle. In spite of several changes and renovations, you can still get a sense of the personalities of both the patrons and the designers, four profoundly creative people who each drew upon classical antiquity to fashion a truly modern place and identity.

The Greek Revival–style Arzner-Morgan house in Los Feliz. Photo: Peter J. Holliday. All rights reserved

Least favorite classically influenced California building: Any of the “mega-mansions” blighting older neighborhoods throughout the Southland. Attaching overscaled balustrades and florid columns to a façade does not evoke the “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur” of classical antiquity. A couple of Sundays ago I dared myself to go into an open house at one built on spec. Like most of these eyesores, it was built literally lot-to-lot. In this particular case the only way for the pool cleaner and gardeners to reach the back yard was to follow a path through the living room, kitchen and family room, and then back again. No amount of faux-marble adornment can make up for bad design.

Weirdest classically influenced California building: The Mount Olympus housing tract off Laurel Canyon. When I call it weird, I am not being pejorative or condescending. I love it. In fact, it is sad that so many people there are remodeling their houses and removing the stucco columns, cypress trees, and other bits of classical ornamentation. I hope a few will remain untouched, and that some of the fountains placed at the intersections will survive our prolonged drought. Mount Olympus captures another, lesser-known face of L.A. in the swinging sixties.

The unmistakable Mt. Olympus sign in Laurel Canyon. Photo: Peter J. Holliday. All rights reserved

The Getty Villa in a sentence: A special place that offers continuing pleasure and inspiration to both scholar and layperson.

Caesars Palace in a word: Camp. High camp. Okay, it takes more than a word! Perhaps this anecdote can capture Caesars for me. One December afternoon in 1976 I was flying home from New York for Christmas break. During the flight LAX was shut down due to heavy fog. We were diverted to McCarran, where it was eventually determined that the airline would put us up at a hotel. About 2:30 a.m. our shuttle bus drove past the brightly lit fountains leading to the main lobby at Caesars. As we got off the bus (mind you, our bags were still on the plane), a speaker fitted into a gilded Augustus of Prima Porta announced: “Hail! Caesar welcomes you to his palace! The white zone is for the loading and unloading of passengers only.” Oh, and we all got a wake up call at 5:00, not long after finally settling into our rooms. Bleary fatigue, however it is induced, is the only way to appreciate Vegas.

Favorite movie set in ancient Greece or Rome: The original 1925 Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ. Directed by Fred Niblo, script by June Mathis, and a cast with Ramon Novarro, Francis X. Bushman, and May McAvoy. It’s one of the great silent spectacles, and with luck you can find a showing featuring a print with the original colored tints and restored Technicolor scenes.

Best part of being an art historian of the classical world: I get to immerse myself in studying material that I love, and learning from colleagues who share that love.

Richard Burton as Mark Antony or Kirk Douglas as Spartacus? Pace Brando as Marc Antony, but Hollywood has taught us that only Brits can play Roman aristocrats. Actually, I’d go with Laurence Olivier as Crassus in Spartacus. They used the Neptune Pool at Hearst Castle as the set for his villa. That is living!

Text of this post © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved.

Comments on this post are now closed.