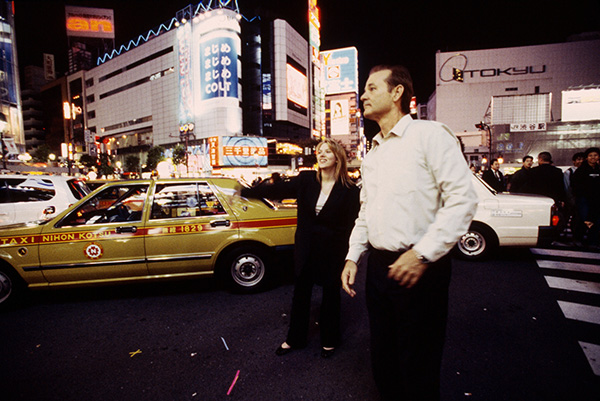

Still from Lost in Translation, 2003. Photofest

In Sofia Coppola’s 2003 film Lost In Translation, two lonely Americans are stuck in a luxury hotel in Tokyo. Charlotte (played by Scarlett Johansson) is a young woman who’s beginning to regret accompanying her celebrity photographer husband on a business trip to Japan, while Bob (Bill Murray) is an actor making millions of dollars doing an ad for a Japanese whiskey. When they get tired of the bizarre game shows on the their televisions and the bad lounge music in the hotel bar, Charlotte and Bob venture out into Tokyo—at first alone, then later together—and are overwhelmed by a city that’s a riot of noise and neon, where nothing makes sense.

Lost In Translation isn’t the movie to watch to understand Tokyo; it’s the movie to watch to understand how tourists experience Tokyo. This is a conscious choice Coppola makes, to show the city through the eyes and ears of Charlotte and Bob, who can’t understand what the locals are saying to them, and are baffled and bemused by the culture. Charlotte watches in awe as young people in arcades turn ordinary life activities like dancing or playing instruments into video games, and when she tries to get back to the “real” Japan by visiting a Buddhist temple, she calls home to a friend and sobs that it was beautiful, but she didn’t feel anything.

Was Coppola being unfair to Tokyo with Lost In Translation, or did she capturing something about the city that even its citizens feel, deep down? She’s far from the only filmmaker to have used Tokyo symbolically. Even 60 years ago, director Yasujiro Ozu was letting the city stand for modernization and the loss of traditional values in his Tokyo Story, while Ishiro Honda made Tokyo represent a Japan devastated by the atomic age in the original Godzilla.

Still from Adrift in Tokyo, 2007. Courtesy of The Japan Foundation, Los Angeles

Satoshi Miki’s quirky 2007 comedy Adrift In Tokyo and Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s 2008 offbeat social drama Tokyo Sonata both tour the bustling, chaotic Tokyo of Lost In Translation, but from an insider’s perspective. The former stars Joe Odagiri as a bankrupt layabout and Tomokazu Miura as the mob debt-collector who offers to pay him a million yen to take a walk across the city with him. The latter has Teruyuki Kagawa as a corporate drone who loses his job, setting off a chain of events that affects his seemingly secure middle-class family. Both film see Tokyo as a place that’s become increasingly mysterious and alienating, even for its residents.

Still from Tokyo Sonata, 2008. Regent Releasing/Photofest © Regent Releasing

Tokyo Sonata is a curious film in a lot of ways, but mainly because of who directed it. Kurosawa (no relation to Akira Kurosawa) has spent the bulk of his career making muted, artful horror films like Pulse and Cure. With Tokyo Sonata he turns the conformity of economic success in the big city into its own kind of horror, which has the unemployed hero, Sasaki, leaving his house in a business suit on his way to his new job cleaning filthy toilets, in the same shopping mall where his wife is spending the money they no longer have. Throughout Tokyo Sonata, Kurosawa recontextualizes the familiar: showing malls from the perspective of the orange-jumpsuited janitors who scatter across it, like the “invisible” stagehands in Noh theater; and showing prosperous-looking jobless men peeling off from the main streets to gather under bridges and in libraries, killing time until they can go home again.

Still from Adrift in Tokyo, 2007. Courtesy of The Japan Foundation, Los Angeles

Adrift In Tokyo is no less melancholy in its way, but Miki’s mismatched heroes are funnier, and have a different relationship with their surroundings. While the gangster Fukuhara makes plans to atone for an unforgivable crime, the sad-sack Takemura tells stories from his youth, as each new stop on their multi-day trip across the city brings up another tragicomic anecdote. Fukuhara and Takemura wind their way through hilly neighborhoods and funky little markets, past music conservatories and the pygmy hippo cage at the zoo. And throughout, they ask questions about modern life in the city: Why do “office girls” hold their wallets up when they’re crossing the street? How do small businesses with no customers make ends meet? And long will it be before all the great places in Tokyo become parking lots?

Ultimately, Adrift In Tokyo defines Tokyo by the memories—both happy and haunting—that its inhabitants associate with all of its nooks and crannies. And the same is true of Tokyo Sonata and Lost In Translation. In Kurosawa’s film, Sasaki overcomes his shame by bonding with his family, creating a mini-city within the city, where he and his wife and sons can avoid other people’s pitying stares by looking at each other. And Coppola’s Bob and Charlotte go their separate ways like kids at the end of summer camp, embracing in the street in the middle of a Tokyo they’ve come to love, because they had someone to share it with.

_______

Tokyo Sonata, Adrift in Tokyo, and Lost in Translation screen at the Getty Center on October 18 and 19; reservations are free. The films complement the exhibition In Focus: Tokyo, which presents the city through the lens of four Japanese photographers.

Special thanks to The Japan Foundation, Los Angeles for their support of the series.

Comments on this post are now closed.