Grave Naiskos of Apollonia (detail), about 100 B.C., Greek. Marble with polychromy, 44 1/4 x 25 x 7 7/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 74.AA.13

An ancient Greek marble gravestone of a young girl holding two doves from about 450 B.C., on view at the Getty Villa and on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, prompts many reactions: wonder at the finesse of the marble carving; sorrow in the face of a life cut short; and curiosity as to the girl’s identity. But the first thing that springs to my mind is BIRDS.

With this girl and her doves, Gallery 207—filled with ancient depictions of women and children—has become a positive aviary; everywhere you look, there are feathered friends. Nearby is a relief from around 400 B.C. of Myttion, who is shown clasping a dove on a gravestone that was once owned by Lord Elgin (of Marbles renown). At the back of the gallery, on another funerary monument, little Apollonia reaches up to hold a dove perched atop a column. Apollonia died some three hundred years later than her two Columbidae-loving counterparts. How might we explain the connection between young girls and doves?

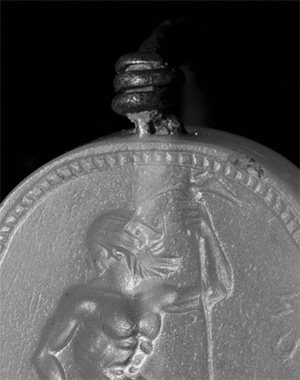

Grave Naiskos of Demainete with an Attendant Holding a Partridge (detail), about 310 B.C., Greek. Marble, 38 x 18 11/16 x 5 7/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 75.AA.63

The birds are sometimes associated with Aphrodite, the goddess of love, probably because of their purported predilection for mating. Indeed, the Getty Villa’s 2012 exhibition a few years ago, Aphrodite and the Gods of Love, included some terracotta votive doves that were dedicated to the goddess at the Etruscan sanctuary at Gravisca. But in the case of the three gravestones, we are far from Aphrodite’s domain. The funerary context necessitates a different interpretation.

The doves might have been associated with death on account of their ability to leave the terrestrial world behind; indeed, they may have been thought of as capable of communicating with the beyond. But at a more mundane level, doves—and fowl in general—were often beloved pets in antiquity. On another gravestone in the gallery, dating to about 310 B.C., Demainete holds a bird—the head is missing, so it is difficult to identify—while her attendant stands by holding a rather dumpy creature, perhaps a partridge. Both of these birds may have been household pets. In commemorating their deceased daughters, families sought to present the girls as they were in life, caring for their playthings. Compare another grave marker of a young woman from about 360 B.C., which shows the dead girl staring longingly at her doll (with, rather inevitably by now, a goose looking on).

These examples might inspire you to go bird-watching in some of the other galleries and even around the grounds. Here’s a quick guide to some other birds at the Getty Villa—no binoculars necessary.

Athena’s Wise Owl

Silver coin (tetradrachm) of Athens, about 460–455 B.C., Greek. Silver, 1 in. diam. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2015.5

For centuries, owls—all but certainly what we identify today as the Little Owls—were something of an Athenian logo. There was a deep-rooted connection between these birds and Athena, the goddess of wisdom, which explains owls’ reputation for being wise. Athena was also the protector of Athens and central to the city’s identity. Find almost any coin minted in Athens, and there’s a good chance that an owl is featured on one side. A silver four-drachma coin from the city, dating to about 460 to 455 B.C.—around the same time as the stele of the young girl and two doves—is one such example, as is another silver coin produced nearly three hundred years later. Flip the coins over and you’ll find Athena herself on the other side.

Given the popularity of owls, it’s no surprise that Athenian vase painters frequently depicted these engaging birds. The Getty Villa collection includes an exquisite example on a red-figure water jar, produced in the early 5th century B.C., on which a cheery owl perches between two sprigs of olive, another important Athenian symbol. The bird even creeps into the gymnasium. On a red-figure cup dating to around 500 B.C., one of the athletes is about to throw a discus adorned with a little owl motif. Perhaps the discus was public property, or its weight accorded with an official standard.

The bedraggled owl at the Getty Villa. Photo: Elizabeth Andres

Although there are no Little Owls in California, as it gets dark in the evening, you might sometimes hear other owl species hooting softly in the trees surrounding the Ranch House. Some years ago, an inexperienced owl found its way into one of the pools at the Getty Villa. He was in a rather sorry state, but was rescued and successfully returned to his natural habitat.

Zeus’s Bird of Prey

Lakonian Black-Figure Kylix, about 530 B.C., attributed to the Hunt Painter. Terracotta, 5 1/8 x 7 11/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 87.AE.31

Engraved scaraboid gem (detail), about 470 B.C., Greek. Blue chalcedony, 11/16 x 9/16 x 5/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.AN.1.12

Birds of prey, particularly eagles, have long captured the imagination. Majestic in size, the eagle was Zeus’s bird, and the two regularly appear together in ancient art, as on an engraved scaraboid gem from about 470 B.C. on which the god’s sceptre is tipped with an eagle. Men looked to the skies for inspiration, and eagles offered powerful omens. In the Iliad, the sight of an eagle struggling with a snake put the fear of god into the Trojans. A similar sight is to be found on a drinking cup made in Sparta around 530 B.C.: the huge eagle’s wings span the full extent of the interior, and the snake wraps itself around the bird’s body, locked in a struggle to the death.

Happily, I’ve never witnessed any encounter like this at the Getty Villa (although I did once see a small snake trying to gulp down a lizard). But I encourage you to look to the skies when visiting, as you might see one of the red-tailed hawks that nest nearby circling overhead. Listen out for their blood-curdling calls.

Hera’s Sacred Peacock

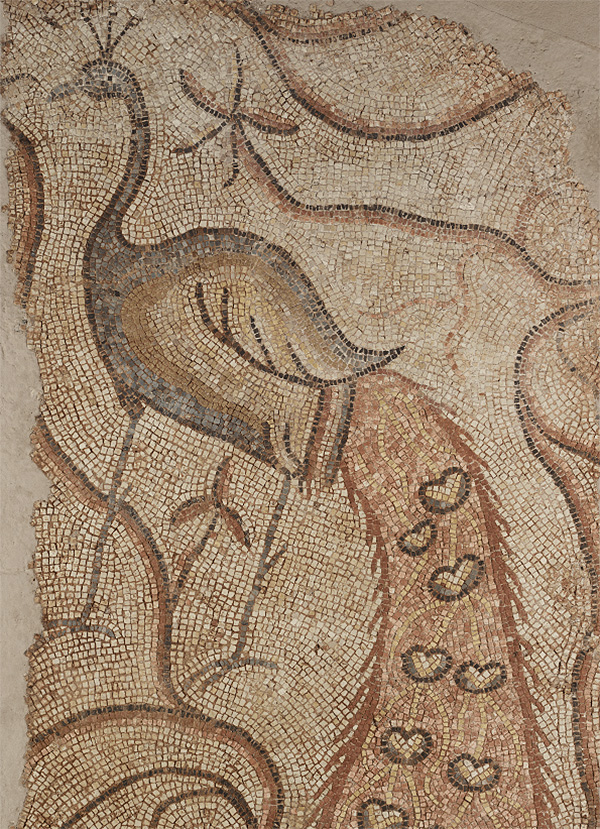

Proudly displayed in the current exhibition Roman Mosaics Across the Empire are two splendid peacock mosaics, probably from Syria. They may have come from a church, where the colorful bird was a common decorative subject. Indeed, St. Augustine recorded the belief that their flesh was incorruptible. Prior to the establishment of Christianity, peacocks were the goddess Hera’s sacred bird. Introduced to Greece from India via Persia, they were—as they remain today—deeply exotic, but under the Romans, they were bred in vast numbers. The Roman rhetorician Aelian (c. 175–235), whose De Natura Animalium is full of fascinating bird chat, wrote, “The peacock knows that it is the most beautiful of birds . . . and is haughty and exults in its plumes, which are its crowning glory.”

Mosaic Panel with Peacock Facing Left (detail), A.D. 400–600, Roman, from Syria, possibly Emesa (present-day Homs). Stone tesserae. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 75.AH.121. Gift of William Wahler

Sadly, there are no actual peacocks at the Getty Villa. In the archives, there is a letter to Mr. Getty dating from just after the museum opened, in 1974, recording a complaint from one visitor who had assumed that a recreation of a Roman villa would include peacocks in the gardens. If you are hankering after these birds in Los Angeles, I recommend visiting the Hollywood Forever Cemetery or the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden, both of which are amply furnished with these resplendent creatures.

There are many more birds I could discuss, including the Villa’s hidden ibis (for a clue as to its whereabouts, watch this video), and if you’re interested in learning more about ancient birds, John Pollard’s Birds in Greek Life and Myth (1977), Geoffrey Arnott’s Birds in the Ancient World from A to Z (2007) and Antero Tammisto’s rich study of Birds in Mosaics (1997) are excellent sources. Instead I will leave the last chirp to the bird that you’re most likely to see when visiting the Getty Villa—the dark-eyed junco. They are the little black-headed birds that flit around the tables of the restaurant and coffee cart. These marvellous fellows can always be guaranteed to lift the spirits, as they happily search for crumbs, entirely oblivious to their many ancient counterparts depicted within the galleries.

Informative and entertaining. Thank you so much for sharing.

Very interesting post!