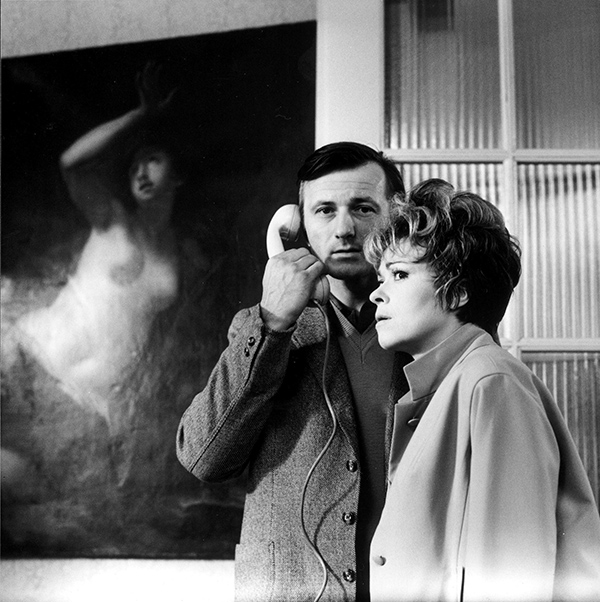

Still from The Ear, 1970. Courtesy of Second Run DVD

Politically engaged art flowered across Soviet Bloc throughout the Cold War, even as westerners heard horror stories about the suppression of dissident artists. In a way, the crackdowns and the creativity went hand-in-hand.

In the 1960s, Czechoslovakia’s government moved toward more openness. The country’s tightly knit filmmaking community followed suit, making darkly humorous movies inspired by the nightmarishness of life behind the Iron Curtain. Jaromil Jires’ The Joke and Karel Kachyna’s The Ear were released after the eight-month period of liberalization in 1968 known as “Prague Spring,” but both owe their existence to the spirit of that movement. And ironically, neither would’ve been made without a stifling bureaucracy to critique.

Still from The Joke. Photo Courtesy of Ateliery Bonton Zlin, A.S.

The Joke and The Ear are about two different men, both named Ludvik, who come to similar understandings from entirely different directions. In The Joke, Ludvik (played by Josef Somr) gets kicked out of the Communist Party and is forced into the hard labor of the “reeducation” camps after he makes a glib remark to the wrong person. The Ear’s Ludvik (Radoslav Brzobohaty), on the other hand, is a rising Party official who begins to doubt the security of his position when he sees signs that his house has been bugged. Both men are go through hell, and emerge asking themselves, “What’s the point?”

The Ear: This Party Is Not What It Seems

In The Ear, Ludvik’s paranoia exposes cracks in his marriage to Anna (Jinna Bohdalova), a brusque, hard-drinking woman who seems “fun” when times are good, but is more of a liability when her husband’s future is in doubt. Kachyna and his co-screenwriter Jan Prochazka use a fragmented structure to capture Ludvik’s predicament, cutting between a swank soiree that he and Anna attend and what happens when the couple comes home. As the movie plays out, the arguments between Ludvik and Anna intensify, and the flashbacks start to take on a different meaning.

Early in The Ear, whenever cinematographer Josef Illik switches to a handheld camera, the film looks like it’s presenting the subjective experience of two tipsy people. And during early scenes at the party, casual conversations (such as a mini-debate about whether it’s counter-revolutionary to pray) seem like a light satire of typical communist-era Czech chitchat. But in light of Ludvik’s growing suspicion that he’s being watched, the subjective shots become more voyeuristic, and the small talk starts to seem more like an inquisition. Meanwhile, the luxuriousness of the party—where everyone’s dressed sharp and eating well—becomes increasingly emblematic of what Ludvik stands to lose if his bosses determine that he’s untrustworthy.

That’s the sharpest point of The Ear: that a political system predicted on proletariat rule keeps its officials in line by allowing them to live well. By the end of the film, Ludvik begins to wonder whether it’s a badge of dishonor to be considered leadership material in a government where the leaders are all cowed and corrupt.

The Joke: Politics Become Personal

What of the other Ludvik, in The Joke? He spends much of the movie trying to get revenge on an old friend named Pavel (Ludek Munzar), who was responsible for convening a tribunal against Ludvik for writing a smart-alecky postcard to a girlfriend saying, “Optimism is the opium of mankind,” and “Long live Trotsky.” Like Kachyna in The Ear, Jires jumps around in time in The Joke, flashing back from Ludvik’s vengeance to show what he went through in the labor camps after Pavel had him ousted from their university. The effect of these dual storylines is to show how politics become personal.

Poster for The Joke (Žert), 1968

Also like The Ear, The Joke is steeped in irony. Ludvik’s big plan is to seduce Pavel’s wife Helena (Jana Ditetova), but he quickly realizes that Pavel and Helena are already an unhappy couple, and that his sabotage will be meaningless. The Joke is an adaptation of a Milan Kundera novel (reportedly based on an incident from Kundera’s youth), and it speaks to the insidiousness of totalitarianism by showing how oppressive governments push people to mistreat each other for no good reason. Ludvik tries to break up a marriage that’s already broken, all because earlier in his life, a group of Ludvik’s peers who knew he was just goofing around turned him over to the authorities.

What’s so bracing about Czech New Wave films such as The Ear and The Joke is how honest and artful they are. There’s a keen wit underlying the rage and frustration, and a sensitive understanding of how the power of the state can warp everyday interactions. Kachyna and Jires took advantage of whatever open windows they could find to make these movies about how silly and dehumanizing their country’s political system had become. For better or worse, they never lacked for material.

Comments on this post are now closed.