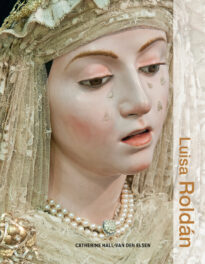

Applying a protective wax coating to Jack Zajac’s 1963 bronze Big Skull and Horn in Two Parts II. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2005.123. Gift of Fran and Ray Stark. Artwork © Jack Zajac

Every Monday—when the Museum is closed to visitors and Getty staff soldier on despite the closure of the coffee carts—the Getty’s outdoor sculptures get washed and rinsed of the week’s helping of dirt, pollution, bird guano, and spider webs.

This was one of my jobs this summer, along with grad intern Raina Chao, who has seen me get drenched at the hose spout on more than one occasion. The Stark collection of 20th-century outdoor sculpture is maintained by the Museum’s Department of Decorative Arts & Sculpture Conservation (DASC), where I’ve been an undergraduate intern for the last 10 weeks. During this time, I’ve gotten an in-depth look at the ways in which conservators examine, maintain, and restore works of art in order to preserve them for future generations to enjoy. Sculpture conservation is a fascinating field because it involves getting to know all of the ins and outs of an object—what it’s made of (right down to the elements), how it was constructed (which may involve many feats of engineering), how the materials age, and how they react to the environment.

Outdoor sculpture is a particular challenge because of constant exposure to the elements. This is why every summer, the sculptures are coated with wax, then buffed to form a protective seal that can also be removed later on. The heat of summer aids this process by keeping the wax melted while it is being brushed on, but can be difficult to work in especially while wearing a respirator and gloves. Though the wax is harmless when hardened, we want to avoid contact with the chemical solvents that are used to dilute the wax in order to make it easier to apply. There are many different types of wax that vary in thickness and color, as well as various solvents that can be used to dilute them. The overall wax-to-solvent ratio is yet another variable to consider. It quickly became apparent that the search for the perfect wax mixture—one that brushes on well, offers effective protection, and brings out the beauty of the metal without looking too opaque—is never-ending in the world of conservation.

This summer, under the supervision of associate conservator Julie Wolfe, we experimented with microcrystalline and carnauba wax recipes as well as several commercial products, recording our observations and making adjustments along the way. By the end of the summer, we arrived at an almost perfect wax recipe that was used on Jack Zajac’s Big Skull and Horn in Two Parts II with great results. The true test will be revisiting the waxes next summer and seeing how they hold up on the sculptures over time.

Comments on this post are now closed.