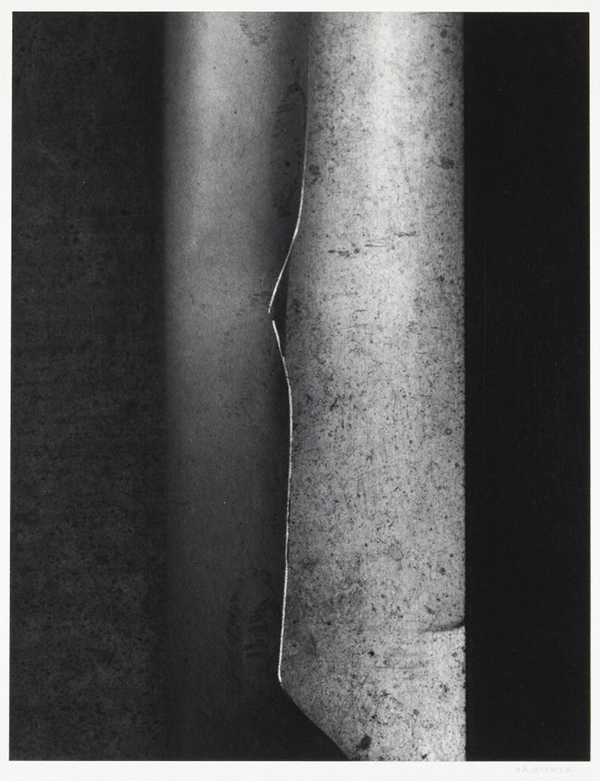

Fall River, Massachusetts 14, 1976, Carl Chiarenza. Gelatin silver print, 11 15/16 x 9 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003.101.6. © Carl Chiarenza

My existence has benefited from experiencing Minor White’s teaching—his presence and example, as much as his words.

I met Minor when I was a student at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) in the 1950s. My exposure to Minor coincided fortuitously with my exposure to other teachers who would have a profound influence on me: Ralph Hattersley, Charles Arnold, Beaumont Newhall, Robert Koch, and Frank Clement.

It was an unusual mix of creative minds, all involved in developing a new educational program focused on the artistic potential of photography. This was at RIT between 1954 and 1957, a time when Minor had moved his life and work from San Francisco to Rochester, New York, and was at a transitional point in his own explorations of teaching, writing, editing, and picture making.

As students we were guinea pigs. For some of us the mixture of tastes was too rich to handle; for others it sparked unforeseen possibilities that we would realize only when we had left Rochester and encountered other ideas.

It is impossible to isolate exactly what Minor did for me as a student all those years ago at RIT. But he provided support for a belief in the photograph as an object worthy of intense effort, as an object in and of itself, apart from anything else in the world.

As Compelling as Music, as Poetry

Notom, Utah, 1963, Minor White. Gelatin silver print, 15 1/2 x 12 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2013.35. Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum. © Trustees of Princeton University

Minor held the conviction that while a photograph may comment on, or refer to, reality, it cannot reproduce reality–whether the maker’s intent is documentation, commentary, or poetry. This understanding counters the mistaken notion that a photograph is a detailed mechanical reproduction of whatever the camera “is pointed at.” In fact, most photographs provide only surface reference to whatever may be centered on the piece of film. Once this is understood, the maker is free to use the tools of the medium to control what will be shared with viewers—just as in music, poetry, prose, painting, or any other art form. Minor helped me understand that I could use my poetic inclinations and musical background to make a photograph that was just as compelling and evocative as a work made by any other form of expression.

While in my second year at RIT, the school started a bachelor of fine arts degree program in photography, developed by Minor and Ralph Hattersley. They were both extraordinarily creative, and they both had a major influence on my career and my photography. They were also different in many ways. Ralph, for example, would tell us to dig through the darkroom’s trash basket and think about what we might do differently with a photo instead of throwing it out.

Minor taught us to spend time looking deeply into pictures, from edge to edge, because “everything in it is important.” One consequence of this training is that I am very critical of pictures, because I see all the parts. We were also required to take classes in painting, design, sculpture, art appreciation, literature, and creative writing, as well as courses in optics, chemistry, physics, and color theory. We withstood, for example, heavy exploration of the zone system and of the manipulation of processing and printing in the darkroom.

Conjuring Nature in the Studio

Untitled (Eye/Sign, Boston West End Window), 1959, Carl Chiarenza. Gelatin silver print, 12 15/16 x 10 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003.101.8. © Carl Chiarenza

Making photographs for the assignments Minor gave us, I found myself doing close-ups, which furthered my early interest in abstraction. I’ve always been attracted to landscape and tried hard to photograph outdoors, but I couldn’t get my pictorial ideas to evolve in nature; so I went into the studio and tried to let collage and light conjure images of my feelings for and about nature.

In 1983 I was invited to participate in an exhibition called Arboretum, for which I made a series of collage pictures called Woods that more directly explored my feelings about nature. I concluded that landscape is really a pictorial construction. In the past, people didn’t refer to nature as “landscape.” Nature only becomes landscape after it is pictured. People bring their feelings to the landscape, and in turn the landscape affects them. My pictures come from a place in between. I believe landscape is an abstract, emotional, pictorial mindset that we construct to examine nature in relation to ourselves—another aspect of my work encouraged by Minor.

Nature is not picturesque. It is often ugly and unruly, which is why I had to struggle to make photographs out in it. By working in the studio, I have control over the light and its effect on the collage. This allows me to alter that relationship in a manner similar to how I “burn and dodge” in the darkroom—another technique reinforced by Minor.

In the studio I play with scraps of paper, and with the lighting on my copy stand to make what I would love to see in nature, but isn’t there. I can’t see it, but I feel it. It’s my way of giving back to nature something that I got indirectly from nature.

Alone with Silence, Spirit, Self

Somerville, Massachusetts, 1975, Carl Chiarenza. Gelatin silver print, 9 1/4 x 12 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2006.31.1. © Carl Chiarenza

Minor was a seeker, a searcher. From Catholicism to Boleslavksy to Zen to astrology, from I Ching to Ouspensky and Gurdjieff, from hypnosis to Schapiro and Wölfflin; from the hell of the military to the depths of music and art and the revelations he found in the photography of Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, and Alfred Stieglitz. And with all he found, he was always generous to others; especially his students, for whom he was always there.

When we were at his apartment he would share his cooking, drinks, and friendship. Yet he was a loner. Concentration, contemplation, and meditation were at his core whether making, studying, listening, or engaging. He preferred to be alone with silence, spirit, self.

Always evident in Minor, too, was a mix of brilliance and innocence. On occasion his escapades brought us distress. His search—most often within nature—never ended. What was he searching? The humanism of self, the love of humanism. That may have motivated his favorite assignment: Meditate, concentrate, focus on a print for an hour. Go within, edge to edge, corner to corner. Now close your eyes and go where that hour moved you. That is where you and image blend. We must study Minor’s work through this experience.

In the mid-1960s Davis Pratt and I put together an exhibition of portraits at Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum. I asked Minor if I could include one of his sequences—series of photographs meant to be viewed in a specific order—and add “Self-Portrait” to its label. Without hesitation he said, “Of course!”

_______

To learn more about Minor as teacher, explore the mock-ups for the many books he composed, assembling hundreds of contact prints and scores of words on topics such as “How to Read Photographs.” Many of the manuscripts are in his archives at Princeton University.

Text of this post © Carl Chiarenza. All rights reserved.

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks