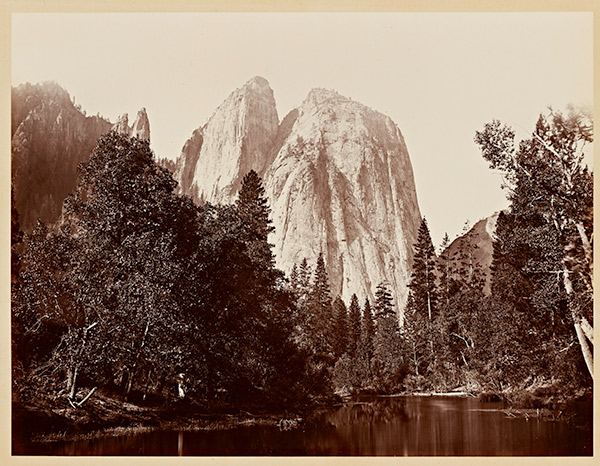

Cathedral Rocks 2600ft., Yosemite, 1861, Carleton Watkins, from the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley

One hundred and fifty years ago this month, with the Civil War raging, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law an act that protected the heart of what we now know as Yosemite National Park.

The signing of the Yosemite Grant Act on June 30, 1864, set aside the dreamy waterfalls and majestic granite outcroppings in Yosemite Valley and the massive sequoias of Mariposa Grove for “public use, resort, and recreation.” It was the first time the federal government protected scenic land for such purposes. The act also set the stage for the creation of the National Park System.

President Lincoln and members of Congress were inspired to make this move, in part, by a portfolio of photographs taken by Carleton Watkins, a San Francisco-based master of landscape photography. It was not easy to be a landscape photographer in the 19th century—Watkins had to mix chemicals in the field, set up portable dark rooms, and deal with dust that could ruin his glass plates. But Watkins had a taste for adventure.

In 1861, the photographer trekked into Yosemite over dirt trails with a team of mules hauling nearly a ton of photographic equipment. One of the items in his cart was a custom-built camera that produced enormous 18-by-22-inch negatives. While Watkins was not the first to photograph Yosemite, the size of his camera produced images that were awe-inspiring and incredibly crisp. These were the most striking images of this place taken by early photographers, explained Elizabeth Kathleen Mitchell, co-curator of an exhibition of Watkins photographs currently on view at Stanford University’s Cantor Art Museum.

Among the images: the sheer face of El Capitan towering over its surroundings, the weathered Cathedral Rocks holding court over a lush and glassy Merced River, and a misty Vernal Falls skipping over boulders.

The Yosemite Valley from the “Best General View”, 1866, Carleton Watkins, from the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley. A similar

Piwyac, The Vernal Fall, Yosemite, 300ft., 1861, Carleton Watkins, from the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley

The Lake Bank, Yosemite, 1861, Carleton Watkins, from the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley

Watkins sold prints out of his studio, exhibited them in New York City, and gave them away to friends. And while there isn’t a clear trail of handoffs between Watkins and the decision-makers in D.C., his photographs became a national and international sensation, said Mitchell.

“In Washington, D.C., people had read about Yosemite or heard about it in newspapers, but very few people had ever visited it,” she said. “The same people who were looking at images of bloody Civil War battlefields could also see there was this untouched Eden on the Pacific Coast. It must have been incredibly appealing.”

After the land had been set aside, Watkins returned to Yosemite in 1865 and worked into the following year as an ad hoc member of the California State Geological Survey team, producing more stunning views. He hand-assembled an album from both trips into a collection he called Photographs of the Yosemite Valley, which he sold to wealthy patrons.

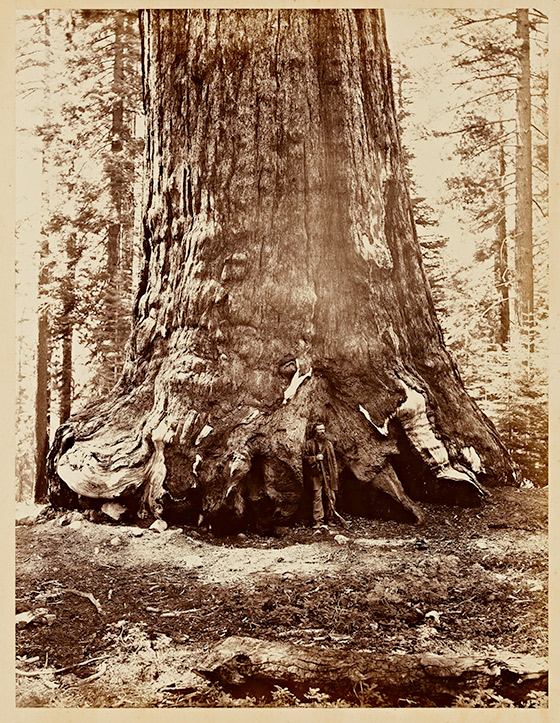

Mitchell’s favorite image comes from this second trip where Galen Clark, the first Anglo-American to enter the Mariposa Grove and the first guardian of the Yosemite Grant, stands in the crook of a massive sequoia known as “Grizzly Giant.”

Section of the Grizzly Giant, 33 ft. diameter, 1865–66, Carleton Watkins, from the album Photographs of the Yosemite Valley

“All in one picture, you see the tree and the man who would become a legend,” Mitchell said. “There’s something about the way Watkins captures him standing against that tree, where you can only see the base of it, but it seems to go on forever.”

Watkins’ images of Yosemite and others he took of the Pacific Coast are on view at the Cantor Arts Center through August 17.

All images courtesy of the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

Text of this post © Zócalo Public Square. All rights reserved.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.