What happens on Mondays when the museum is closed to visitors? While schoolchildren enjoy amazing group tours in some galleries, Museum folks are busy installing works of art in others.

To install a new masterpiece in the Impressionist gallery this week, we needed an entire Monday, plus a few early-morning hours before our opening to the public at 10:00am on Tuesday! That’s because the new arrival is the 1,400-pound marble group by Auguste Rodin, Christ and Mary Magdalene, that the Museum acquired last June. It was time to remove it from its temporary exhibition gallery in order to install it in the permanent collection.

Lowering the piece

Moving and placing it onto warm wax

Adjusting the lights

Mounting the labels

Christ, Thinker, Poet, Artist?

Auguste Rodin invented and composed his works very quickly, and sometimes gave them several titles. For instance, he said of this group: “I call it the Christ and Mary Magdalene, but I could also have called it the poet, the thinker, or the artist—in a word, the man whom other men always crucify and whom women always comfort.” As a result, Rodin also called the group The Genius and Pity and Prometheus and the Oceanide. This mix of the sacred and the profane reflects Rodin’s feelings about the intrinsically tragic nature of creation.

An Intriguing Creation Process

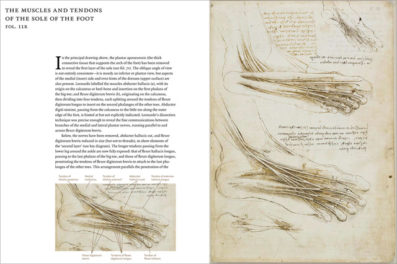

Christ and the Magdalen, ca. 1894, Auguste Rodin. Plaster and wood, 84.5 cm high. Musée Rodin. © Musee Rodin – Adam Rzepka

From about 1890, Rodin started making works from figures he had created previously, in particular an important collection of plaster casts that he kept in his studio. Mary Magdalene in the present work is an example of this creative process: it derives from a work Rodin had composed for the souls of the damned on The Gates of Hell. It then became an independent figure called Meditation, and was again used in Monument to Victor Hugo, as a muse called The Inner Voice.

The plaster model of the group, in the Rodin Museum in Paris, is dated to around 1894. The first marble version was commissioned by August Thyssen (1842–1926), an iron industrialist who collected a number of works by the sculptor. Art collector Karl Wittgenstein, who visited Rodin’s atelier in 1907 and saw the first version in progress, commissioned a second marble.

No other versions of this sculpture were carved, since Rodin had pledged to Thyssen not to make more than two marbles of the subject. And unlike most of Rodin’s works, this composition was never cast in bronze, although the idea was mentioned by the artist in a letter to the dancer Loïe Fuller dated December 1914.

The Work’s Patron

Karl Wittgenstein (German, 1847–1913), one of the richest industrialists of the late 19th century and the father of the famous philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, was also a significant patron of the fine arts. Musicians such as Johannes Brahms, Pablo Casals, and Gustav Mahler frequented his palace.

One of Karl’s other sons, Paul, became a concert pianist; after he lost his right arm during World War I, Sergei Prokofiev and Maurice Ravel composed concertos for his left hand. Karl owned paintings by Gustav Klimt and was an important supporter of the Vienna Secession, financing a huge part of the Secession’s exhibition hall.

Rodin’s Favorite Marble Carver

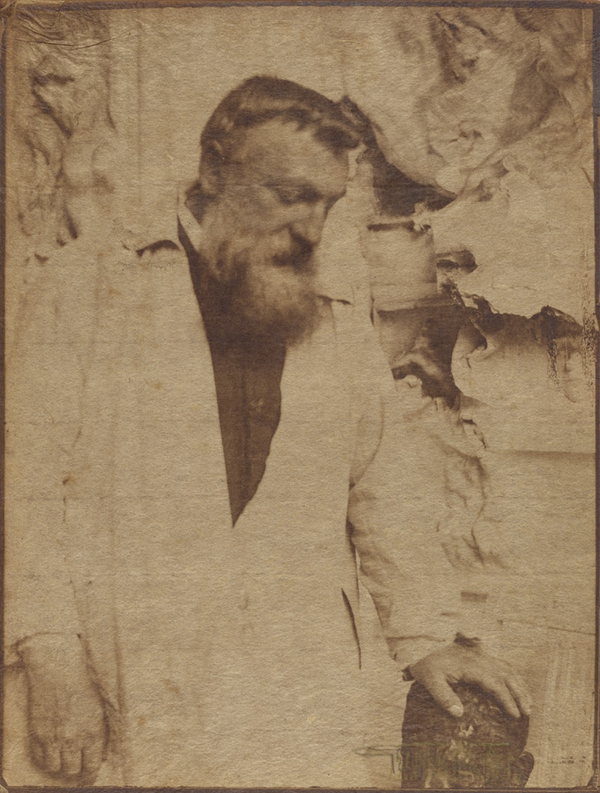

Auguste Rodin, 1905, Gertrude Käsebier. Platinum print. The J. Paul Getty Museum

To honor the many commissions from his demanding clientele, Rodin from very early on relied on talented carvers to realize his compositions in marble. Victor Peter (French, 1840–1918), who carved both of the marble pieces of Christ and Mary Magdalene, was his most able and preferred assistant. Peter was awarded a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle in 1900 and became a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1901. His independent works include small reliefs and medals, among which is an important series of portraits of contemporary artists, including Rodin.

The master always retained close control over the carving process and only employed assistants who understood and were able to faithfully manifest his style, such as Victor Peter. In fact, he argued with any who tried to leave their own artistic mark on the marbles he entrusted to them.

Rodin and Michelangelo

Rodin had a very strong relationship to the medium of marble. This was due in part to his trip to Italy in 1876, where he saw and admired the sculptures of Michelangelo in Florence. The influence of the great Renaissance master is evident in Christ and Mary Magdalene, not only in the dramatically contorted female body but also in the use of the “non finito,” the practice of leaving an artwork in an intentionally incomplete state.

In Florence, Rodin saw Michelangelo’s Slaves, whose expressions are enhanced by their unfinished aspect—the figures seemingly trying to liberate themselves from their blocks of marble. The compelling strength of Christ and Mary Magdalene results similarly from the massive block left conspicuously rough at the bottom and on the back, and from the contrast with the highly polished surfaces of the bodies. In the very distinctive shape of Christ’s face and the position of his legs, one can also see the influence of medieval crucifixes, which Rodin likewise admired.

Rodin and His Painter Friends

With the new display of Rodin’s marble group in the Impressionist gallery, it’s as if old friends are meeting again!

Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, and Sisley all exhibited together at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris. Paintings by these artists, together with sculptures by Rodin, were reunited in 1887 for the gallery owner’s sixth international exhibition. In addition, Rodin and Monet were bound by a lifelong friendship and by reciprocal admiration: they even organized an exhibition of their works together in summer 1889, which was a huge success with both the public and critics. And last but not least, Rodin had a small collection of paintings including three works by Van Gogh, one by Renoir, and one by Monet.

Rodin’s Christ and Mary Magdalene is now on permanent view in its new home at the Getty Center, just steps from Van Gogh’s Irises.

Comments on this post are now closed.