What does the beginning of a great artist’s career look like? Rare signed works—the drawn Self-Portrait by Albrecht Dürer aged 13 and Anthony van Dyck’s arresting painted Self-Portrait at about 16—reveal their startling talents as young teenagers, an age when most artists are still diligently learning the rudiments of their art. Many painters, including Titian and Rubens, were conceptually ambitious from the first, but a bit awkward in execution.

What of youthful Rembrandt, one of the most extraordinary and distinctive artistic personalities in the history of art? He too painted and etched his own image frequently as a young man, but the very earliest moments of his career—small, dramatic multi-figure compositions—are still being discovered.

Spectacular Surprise—Rembrandt in New Jersey

On September 22, 2015, a panel painting of figures in an interior (one described as an unconscious “lady”) appeared at auction at Nye & Co. in New Jersey. It was catalogued as “Continental School Nineteenth Century.” Despite the discolored varnish, condition issues, and awkward additions to the panel, the curious figure group struck knowledgeable viewers as singularly important. After vigorous bidding, the so-called Triple Portrait with Lady Fainting was acquired by a European phone bidder. The subsequent announcement that the painting was thought to be by Rembrandt ignited enthusiasm and conversation around the world.

After conservation treatment (and removal from its ornate gilded frame), the painting looked quite different. Its brilliant palette, descriptive brushwork, and tightly arranged figures confirmed that it was, in fact, related to the earliest known paintings by Rembrandt, depicting three of the senses: The Three Musicians (Allegory of Hearing), The Stone Operation (Allegory of Touch), and The Spectacle Seller (Allegory of Sight). Close scrutiny also revealed Rembrandt’s earliest signature, which you can see at the upper right, cleverly placed on the portrait of a man tacked to the back wall: RHF (Rembrandt Harmenszoon fecit). The rediscovered Rembrandt was the long-lost Sense of Smell from this very same series, painted when the artist was about 18.

Unconscious Patient (Allegory of the Sense of Smell), about 1624–25, Rembrandt van Rijn. Oil on panel, 8 1/2 × 7 in.; entire panel (with later additions), 12 1/2 × 10 in. Image courtesy of The Leiden Collection, New York

Detail of Sense of Smell showing Rembrandt’s earliest signature, just visible at the very top right (“RHF”). Image courtesy of The Leiden Collection, New York

The panel had been set into another, larger panel, probably in the 18th century, to create a more elaborate composition. This process, which had also been carried out on the other three paintings, helped confirm that the new discovery belonged to the group (more on this story here). The conservation treatment also revealed the array of tiny implements on the back wall in the upper left corner, as well as the glass jar just below them.

In the past, scholars had been divided over the attribution of the three senses, which were rediscovered in the early 20th century. Along with the panel additions, the paintings were dirty and overpainted in areas, making it difficult to assess their quality. After careful cleaning and study in 1988, however, it became clear that these small, dramatic scenes share many stylistic characteristics. This left little doubt over their authorship.

The treatment of certain effects—such as anatomical details and the contrast of light and shade—are tentatively handled, suggesting the Senses series probably pre-date Rembrandt’s exposure to the powerful works of Pieter Lastman, his teacher and mentor, in Amsterdam around 1625.

Rembrandt’s Senses Reunited

Thanks to the generosity of the Leiden Collection, which owns all three panels, Sense of Touch and Sense of Hearing will be displayed at the Getty along with Sense of Smell, the newly acquired companion painting. They will hang in our Rembrandt gallery, on public view side by side for the first time in over 300 years.

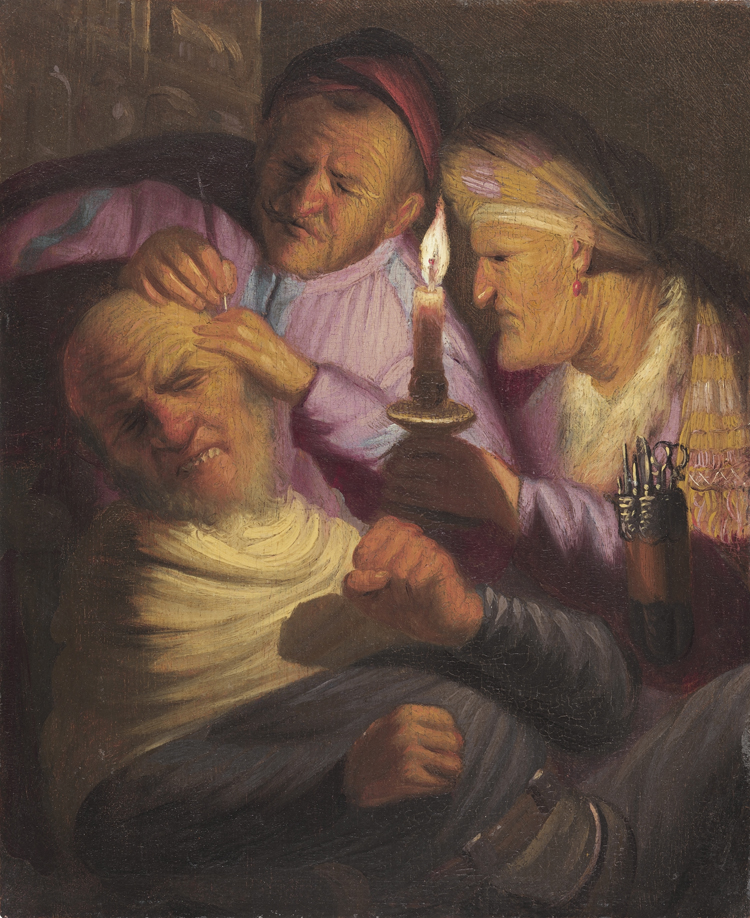

The Stone Operation (Allegory of Touch), about 1624–25, Rembrandt van Rijn. Oil on panel, 8 1/2 × 7 in. Image courtesy of The Leiden Collection, New York

What do we see in these paintings? In each composition, Rembrandt visualized one of the five senses through a human activity, adding moralizing commentary as was the style in art of the time. Sense of Touch portrays a man writhing in pain as a quack doctor performs surgery by the light of a candle held by a suspicious-looking assistant in outlandish garb. The operation, to remove stones from his head, was a proverbial cure for foolishness. In Sense of Hearing, the satire is less biting: a youth, a middle-aged man, and an older woman sing harmoniously together.

The Three Musicians (Allegory of Hearing), about 1624–25, Rembrandt van Rijn. Oil on panel, 8 1/2 × 7 in. Image courtesy of The Leiden Collection, New York

Sense of Smell adds an especially interesting element to this trio. Rembrandt devised an unusual and witty narrative: on the right, a young well-dressed man lolls unconsciously, while two quacks hold a handkerchief, presumably with smelling salts, under his nose and watch with anxious expressions for him to revive. There are few clues to identify his plight, but his bare arm suggests he has undergone a common treatment for many illnesses—bloodletting—and fainted.

The other two senses in the series are, of course, sight and taste. The Spectacle Seller (Allegory of Sight) is in the collection of the Lakenhal Museum in Leiden, but Sense of Taste remains as yet undiscovered. It, too, probably features a small group of figures in dim room, drinking and carousing in brilliantly colored costumes. It may yet be out there, waiting to be rediscovered—keep your eyes peeled!

The Spectacle Peddler (Allegory of Sight), about 1624–25, Rembrandt van Rijn. Oil on panel, 8 1/2 × 7 in. Museum De Lakenhal, Leiden. Image: Wikimedia Commons

These paintings show a young, developing artist, but Rembrandt’s extraordinary ability to convey emotions and create a compelling narrative on a small scale is fully evident. As a curator specializing in Dutch art, I find these works fascinating and important, and hope you will as well. We can see in them early signs of the enthusiastic praise Rembrandt would receive only five years later for his “liveliness of emotions.”

See Rembrandt’s Senses, alongside other paintings by Rembrandt, at the Getty Center in Gallery E205 from May 11 to August 28, 2016, in The Promise of Youth: Rembrandt’s Senses Rediscovered.

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks