On June 13 and 14 the Getty Museum hosted Arts Integration + California: A Convening, which featured various models of arts integration from across the state. In addition to keynotes, case studies, and group discussions, brief “Spark Talks” gave five speakers less than 10 minutes each to highlight one or two big ideas.

The Spark Talks were packed with actionable ideas for integrating the arts into the K–12 classroom—here are my takeaways from the day.

1. Improve Academics by Using Creativity

Dennis Doyle is the executive director of Collaborations: Teachers and Artists (CoTA), which offers a three-year professional development program to help teachers integrate the visual and performing arts into the teaching of Common Core subjects.

In his talk, Doyle highlighted a study on the program led by James Catterall of UCLA, which examined qualitative data on students’ creativity, quantitative data on students’ performance over time, and the effectiveness of student assessment techniques. The study team asked: What conditions are necessary to teach creativity? What are teachers, artists, and students doing that is enhancing creativity? What tools are necessary to sustain creative teaching and learning?

The research yielded a fascinating finding: for students to succeed, teachers must be willing to be vulnerable. It also noted that 87% of participating teachers believed that CoTA positively impacted students collaboration, 74% noted positive impact on students’ creativity, and 88% reported positive impact on students’ depth of understanding of academic content.

2. Focus on Equity First, Quality Second

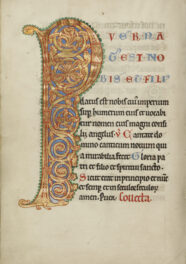

Denise Grande is director of Arts for All at the Los Angeles County Arts Commission. She took us to the 30,000-foot level, asking us to move away from “deficit thinking” and recall that arts integration has been around for a very long time—indeed, since Leonardo da Vinci. She also reminded us that the “arts are not a special treat but an abundant source of nutrition.”

In a room of dedicated arts practitioners and integration specialists, Grande urged us to focus on equity and scale. Her argument: arts advocacy can no longer be about one student in one classroom, but about arts instruction for all students. We can’t increase the quality of instruction that doesn’t exist, she said; we must first address equity and only then tackle quality.

3. Prioritize Arts Integration in the Community

Jeannene M. Przyblyski took yet another tack. With self-effacing humor, she framed her thinking around placemaking and civic art. Przyblyski is the provost at CalArts, and to her the ultimate aim is to build whole people who are resilient citizens connected to one another. She declared that we should live in substantial and vibrant places, and provided case studies and probing questions about the future of arts integration.

In one example, she compared the Florence-Firestone community in L.A. County with Tremé, a historic neighborhood in New Orleans, citing their shared indicators: high levels of poverty and unemployment; struggling schools; random and persistent violence; high levels of youth incarceration; radical demographic shifts over the last 10–20 years; and people with long-standing roots in the community. Why, she asked, does Florence-Firestone struggle for identity while Tremé is a model of resilience? She found that residents of Tremé identify proudly with their neighborhood and benefit from strong traditions of participation in music, dance, and art.

Arts integration develops empowered individuals, a strong engaged workforce, and resilient communities, said Przyblyski. And it must start in the community: in schools, libraries, parks, community centers, and museums. We need both classroom education and radical strategies for imagining how we create, facilitate, and inhabit public space.

4. Use Imagination to Drive Learning

Diana Rivera, a researcher and facilitator at Saybrook University, brought us deep into the psyche of the teaching artist, whom she argued is a vehicle for human relationships.

Rivera asked us to consider how imagination is linked to creativity. In her research, she found that imagination is an altered state of consciousness, and that the act of play increases empathy when linked to creativity and the arts. She found that imagination—even more than empathy—is critical to the advancement of learning.

5. Treat the Arts and Academics as Equal

Shannon Wilkins is head of educational leadership programs and the visual and performing arts at the Los Angeles County Office of Education. She discussed a three-session training she developed for school principals in partnership with the L.A. County Arts Commission, which focused on teaching creativity within Common Core standards.

Wilkins’s “Teaching Creativity” training consists of three parts, with guidance on:

• Integrating the arts into language arts curricula,

• Adding the arts to science, technology, engineering, and math instruction, and

• Implementing arts integration at the school level.

She recommends teaching both the arts and academic subjects equally, and not placing one in service of the other. Since its inception six years ago, the County has trained over 600 instructors and won two major awards.

Wilkins also shared her preferred definition of arts integration, developed by the Kennedy Center:

“Arts integration is an approach to teaching in which students construct and demonstrate understanding through an art form. Students engage in the creative process which connects an art form and another subject area and meets evolving objectives in both.”

The major obstacle to arts integration in secondary schools, Wilkins said, is instructors’ fear of not being taken seriously. She recommended creating strong modalities for middle and high school students that use art objects to make learning come alive—using paintings and sculptures to show history, place, and time.

Ways Forward

The various strategies presented in these talks—from equitable delivery of the arts to methods for teaching creativity—offered a dynamic overview of current projects. But if arts are truly to be for all, our next step must be to reach all principals, teachers, teaching artists, and students, not just the few served by pilot programs.

In discussions at the event, some colleagues suggested mandated hours in the day in which the arts are taught. Others argued that integration is the best of both worlds—exposure to the visual and performing arts with fulfillment of other subject area goals.

These Spark Talks made clear to me that we in the field have tremendous models and resources for implementation strategies. I hope that we can now develop larger, long-term strategies to ensure that we are reaching every school, every classroom, and every student with the best ways of learning that include creativity and the arts.

Hello, my friends to the south. Very inspiring and timely. Talk about thought leadership — these are unique and profound viewpoints. I recently took on a new position as the Executive Director for San Francisco USD’s long-time dream, the building out of a block in the Civic Center arts corridor for the arts high school and a city-wide Arts Education Center. Our goal is to reach 57,000 students and to include the arts as a key component in closing the achievement gap and at the same time inspiring teachers, many of whom have rich arts backgrounds that were considered liabilities in the NCLB era. I hope to create a summit here, possibly in the spring, to bring together great thinkers as we plan the Center. Thanks to the Getty for hosting this, and don’t be surprised if you get an invitation from us to spend a few days here and help us in this grand effort. If there are any materials you are able to forward, please use my District e-mail address, harrisd2@sfusd.edu

Thanks and bravo for a really meaningful thought leadership event.

Very carefully worded and researched article.

Is there any research on the difference between certified, college educated teachers and non certified artists?

Is there any correlation between higher order thinking, synthesis, evaluation and creativity and the training of skills and attitudes?

Finally, is there are research why visual arts has struggled to be taught in schools, museums and through arts councils and is not well funded by corporations and school funded programs?

Dear colleagues:

Kudos to all who keep the ATRS fires burning for both students and teachers! I applaud you!

This ‘vulnerable’ bridge of understanding and knowledge is a real thing in K12. This Arts Education bridge has been burnt, rebulit and moved so many times it has confused the troops in the trenches. Much like da Vinci’s portable bridge served to outwit its opponents!

I say this having trained willing teachers with arts training who shy away from sharing their adult projects with fellow teachers, unwilling to RISK rejection or reveal their inner self. Yes. It is scarey to go on stage. But. In this techno age of touch screens – we are losing touch with human connectivity.and students need to be shown how to step out of themselves.

Our teachers need training on how to take risks and survive failures. In fact, love failure for its teaching tools.

When schools still connect and target test scores (my STEAMS school was 932 last year) students are not allowed to risk.

By thw way,my principal alloted 500.for our VAPA program for 850+ students for the year. If my amazing parents did not believe so much in the arts and contribute so much more, there would be no program with respect to funding.

I will say, however, we have become pretty creativd with paper, cardboard and cockeyed remnants to make some incredible projects!