A room full of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt’s Character Heads—currently at the Getty Center as part of the exhibition Messerschmidt and Modernity—may be the best place in L.A. right now to observe neurobiological reactions to human expression. The heads are not the only ones making faces. Looking around, you’ll see an equal number of visitors grimacing, cringing, and contorting their features in response.

I’m not entirely certain what Messerschmidt, possibly mentally unstable at the time, had in mind while creating the heads, nor am I sure if visitors’ initial reactions to the sculptures mirror my own discomfort, but one head stands out: A Hypocrite and a Slanderer. This particular head triggered an array of emotions and a barrage of images culled from my subconscious, which are only now making some sense. Unexpectedly, the incongruous title—created after the artist’s death—helps me analyze my response.

A hypocrite? A Hypocrite and a Slanderer, after 1770, Franz Xaver Messerschmidt. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, European Sculpture and Decorative Arts Fund, and Lila Acheson Wallace, Mr. and Mrs. Mark Fisch, and Mr. and Mrs. Frank E. Richardson Gifts, 2010 (2010.24). Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, N.Y.

The sculpture’s refusal to engage, looking down and forever introverted, achieves quite the opposite effect of its character. It seems as though the head doesn’t want to be there, doesn’t care, which challenges us to get its attention. We don’t like being ignored. Imagine stepping into a room with nothing but this sculpture. A possible reaction by the viewer: “Hey, look at me!”

A Hypocrite and a Slanderer reminds me of similar reactions to the contemporary sculpture Big Man by Ron Mueck. A huge, naked, hairless man with similarly gloomy features coils up against the corner with just as little desire to be in the room as Messerchmidt’s piece. Big Man is a contradiction of childish pouting in a grown man’s body, sporting a troubled expression and seemingly wanting to be left alone, yet forcing the viewer to take a closer look just the same.

We wouldn’t dare approach either figure as easily if he were alive and breathing.

A slanderer? Untitled (Big Man), 2000, Ron Mueck. Pigmented polyester resin on fiberglass, 80 1/4 x 47 1/2 x 80 1/2 in. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Museum Purchase with Funds Provided by the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Bequest and in Honor of Robert Lehrman, Chairman of the Board of Trustees, 1997–2004, for his extraordinary leadership and unstinting service to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. Photography by Lee Stalsworth

Both sculptures, with their bulletlike heads and thick necks, relate to our culture’s fluid perception of big and bald.

Kola Kwariani in a still from Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing (1956). © MGM Home Entertainment

A figure that came to mind immediately is wrestler and chess player Kola Kwariani. Kwariani is most memorable for his role as Maurice Oboukhoff in Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing, in which he embodies his real-life contrast of gentle brains and explosive brawn. Other notable TV and film performances crossed my mind. How else could Michael Chiklis have made such an easy transition from playing a corrupt and brutal detective in The Shield to humorous superhero The Thing in Marvel’s Fantastic Four?

Cover of Kingpin #1 (2003). © Marvel Comics (left). Cover of The Mars Volta’s De-Loused in the Comatorium (2003) designed by Storm Thorgerson (right)

Examples from comic books are many and mostly on the villainous side (think the Kingpin), but the images don’t end there. Unwillingly, even an unpleasant photo of Damien Hirst and a severed head, previously on display at the Tate, popped to mind. So too did a head in my record collection—a gold, luminous head on a plate on the cover of The Mars Volta’s debut album De-Loused in the Comatorium.

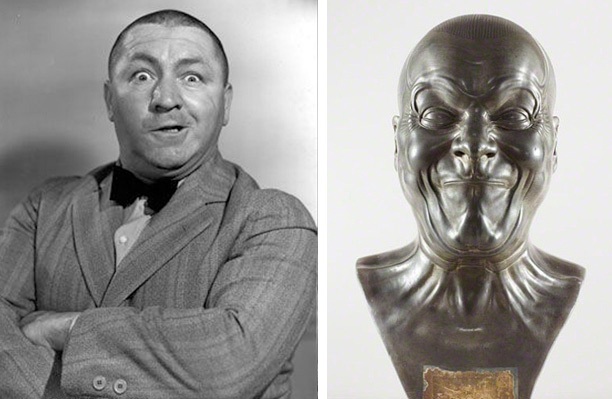

Ultimately, I had to smile despite initial uneasiness, because the final image that came to mind was that of someone who could truly go head-to-head with Messerschmidt in the exhibition’s Expression Lab: everyone’s favorite stooge, Curly Howard.

Curly Howard. © 2012 C3 Entertainment, Inc. (left). A Strong Man, after 1770, Franz Xaver Messerschmidt. Tin-lead alloy. Private Collection (right)

Comments on this post are now closed.