One small but powerful object stands out among the artifacts excavated from the ancient city of Morgantina in central Sicily, now on loan to the Getty Villa from the Museo Archeologico Regionale of Aidone and on view in Gallery 104. Made of metal and covered in spidery writing, instead of being a gift offered to the goddesses Demeter and Persephone like the clay statuettes, lamps, and vases also in the installation, it had a purely malicious intent: to inflict pain.

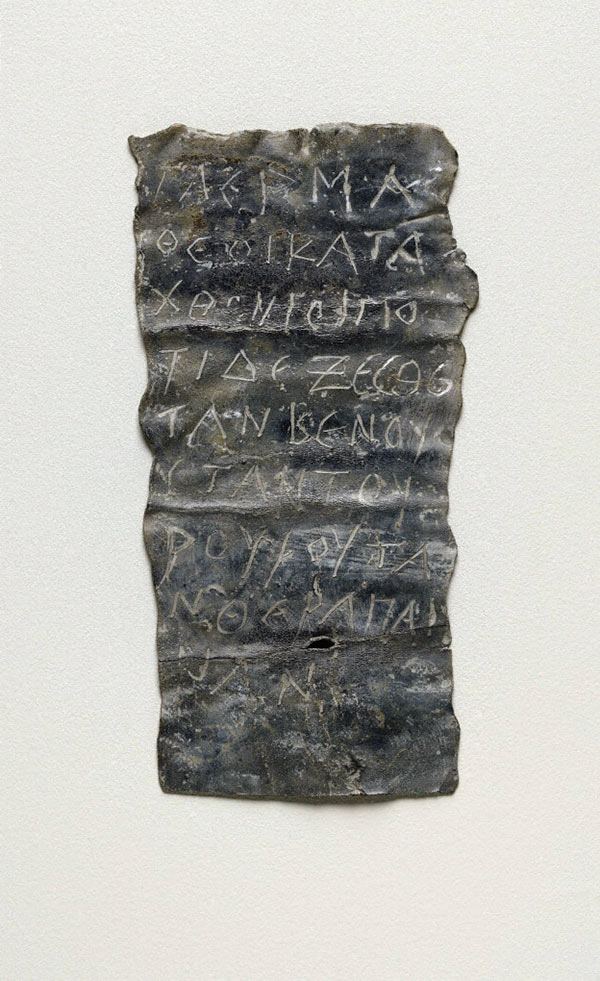

Curse Tablet, about 100 B.C., found in Morgantina, Sicily. Lead, 3 11/16 x 1 13/16 in. (9.4 x 4.6 cm). Museo Archeologico Regionale of Aidone

Known as curse tablets, objects such as this one were made by scratching a curse onto a thin rectangular sheet of lead using a stylus or pointed tool. The lead was then heated slightly and folded up to hide the writing. The tablet could be rolled around magic herbs, or even animal or human hair (from the intended victim!) for extra potency. Or the folded lead could be pierced with nails (to pin down the target, giving the Latin name defixio). The curse tablet was then thrown into a sacred pit at a sanctuary, a watery chasm at a spring or pool, or a newly dug grave (preferably of someone who had just died young or violently), ensuring its delivery to the Gods of the Underworld who would carry out the punishment.

Curse tablets were a means of revenge (or just venting) for both the ancient Greeks and the Romans. Some of the earliest examples, dating to the 5th century B.C., have been discovered in the Greek colonies on Sicily, and the practice extended to Roman Britain, where over 100 curse tablets from the 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D. have been recovered from the sulphurous natural hot springs at Bath, England. Archaeologists can carefully unroll the lead, revealing the hidden curses within. Seeking bodily harm, mental or physical incapacitation, or death, these curses were made against thieves, or rivals and enemies in politics, athletics, domestic disputes, and affairs of the heart. The texts generally follow a simple formula: invoke the name of the gods, describe the desired punishment, name the victim, and explain why they have incurred your wrath. A number of the tablets from Bath concern clothing stolen while their owners were enjoying the healing waters! Greek examples might call for an orator’s tongue to stop working during his legal case against the writer.

The curse tablet now at the Villa was thrown into a pit in the sanctuary of the Gods of the Underworld at Morgantina around 100 B.C. In total, 10 curse tablets have been excavated from this pit. Incredibly, four of these, including this one, all curse the same woman! Using almost exactly the same wording, these four call on the Gods of the Underworld to take a slave-girl named Venusta back with them to the realm of the dead—in other words, for her to go to hell. The one on view at the Villa reads as follows:

Gaia, Hermes, Gods of the Underworld, receive Venusta, slave of Rufus.

Could all four curse tablets be from four different people who all really disliked Venusta? Or was it the same person who kept coming back to curse her again and again, irritated that the curse wasn’t working quickly enough? Unfortunately we don’t know who made these curse tablets (they didn’t sign their name), and so it remains a mystery why they had it in for poor Venusta. She, we assume, eventually did join the realm of the dead—though we can’t say whether the curse tablet hastened the process.

Installation view of The Sanctuaries of Demeter and Persephone at Morgantina featuring objects from the Museo Archeologico Regionale, Aidone, Sicily, at the Getty Villa. The curse tablet is at center in the case.

V. interesting! Are the curse tablets for Venusta inscribed in the same hand??

Thanks, Abigail. Great question!! Unfortunately I don’t know for sure. I have only seen the one that is now on loan to the Villa. The tablets have been published in the American Journal of Archaeology (1979, pp. 463-4) but any similarities in the scripts wasn’t mentioned. Even if they are by the same hand, it could be the hand of a scribe, paid to write the curses, since literacy levels were relatively low in antiquity.