Saskia Wilson-Brown is frequently on the move. When we first spoke, she was catching a plane to London. Once back in Los Angeles, she had a film festival, the AIX Scent Fair, and the Art and Olfaction Awards lined up—and then a trip to Cuba with family—before we were able to connect in person.

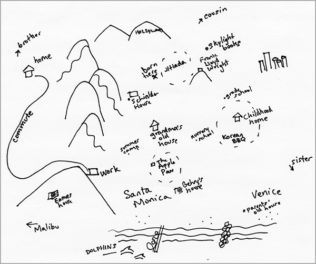

A beautiful and creative free spirit, this Cuban-English-American (and French-raised) Angeleno launched the Institute of Art and Olfaction (IAO) four years ago. Since then, she’s devoted much of her time to showing people like you and me that anyone can mix scents—it doesn’t always take a master perfumer—and that fragrance workshops are a fun way to learn more about yourself and the world. Saskia also works on an incredible range of scent-based creative projects—evoking historic Pasadena through smell at the Huntington, adding a smell dimension to oral histories at the Pulitzer, collaborating with Maxwell Williams on a scent-based zine to launch at the AIX Scent Fair at the Hammer.

Exterior of the Institute of Art and Olfaction (IAO) in Chinatown, Los Angeles. Photo: Allison Ramirez. © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved

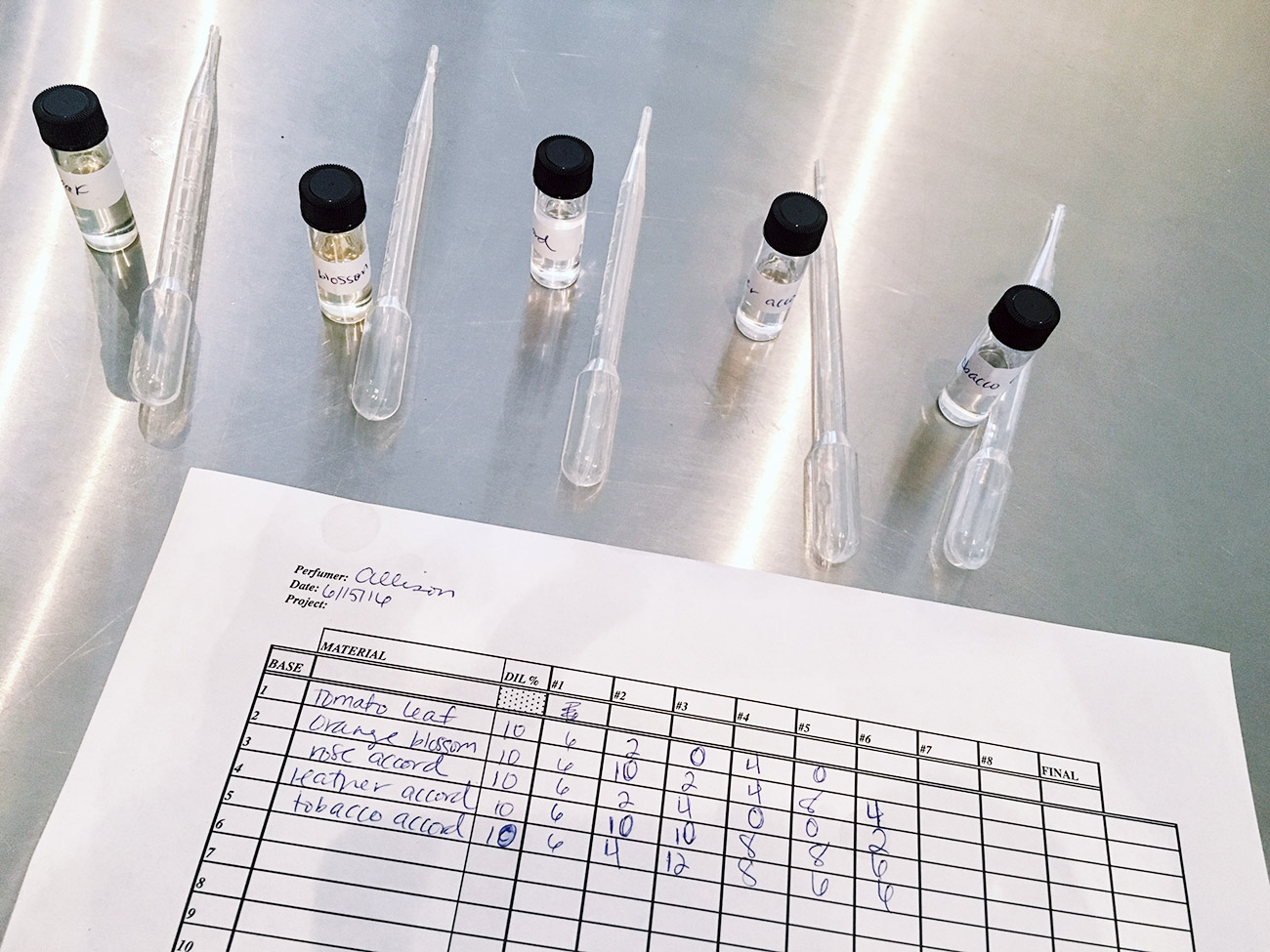

I recently attended one of Saskia’s open sessions at IAO and, with her gentle guidance, I created my own fragrance. The session took place at the Institute’s warm, welcoming Chinatown space and, over the course of two hours, I was able to smell a wall-full of essential oils as well as synthetics, and then choose five that appealed to me. The result, after a bit of trial and error, was a fresh, summery floral scent that I was able to take home with me, along with my very own fragrance recipe that I’ll be able to recreate when I run out.

Scent vials at the Institute of Art and Olfaction (IAO). Photo: Allison Ramirez. © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved

A perfume worksheet at the IAO workshop. Photo: Allison Ramirez. © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved

Not only does Saskia hold these open sessions at IAO, she’s also led fragrance workshops at the Getty Center and Getty Villa inspired by exhibitions and the collection. I asked her to share some of her fragrance knowledge, background on her Getty workshops, the programs IAO offers, and why scent can trigger an emotional response.

Allison Ramirez: Tell us about the fragrance classes and demos you’ve led at the Getty.

Saskia Wilson-Brown: I’ve led several workshops at the Getty Villa and the Getty Center devoted to exploring scent in the context of history and art—including the use of scent under Emperor Constantine in Byzantium, the use of scent in ancient Greek and Roman aphrodisiacs, and the development of the fragrance industry in the century leading to the French Revolution.

Can you share a few of your favorite fun facts from these workshops?

Did you know that Emperor Constantine set aside a budget for aromatic materials when he built his basilicas? And that Louis XIV believed that his personal scent needed to be a reflection of the glory of France? And that Aphrodite was closely linked to the smell of roses?

(Editor’s note: For lots more great stories from the Getty workshops, see Saskia’s posts here on The Iris about Byzantium and Louis XIV.)

Scent is supposedly the strongest memory trigger. Certain flowers or perfumes bring back feelings of long-forgotten places, people, and experiences. Why is this?

The first thing people typically bring up when they’re talking about a smell is that it reminds them of mom, dad, childhood, and so on. There’s no doubt that scent is a primal sense, and it triggers memories—similar, in my mind, to how a song can remind you of your first slow dance.

Poetic aside, the reason for this is simply anatomical. Scent is processed through a part of the limbic system called the olfactory bulb. The olfactory bulb, in turn, connects directly to the hippocampus (responsible for associative learning) and the amygdala (responsible for emotion, among other things). Thus we are wired to associate smell with people, emotions, places. When you first hug a new lover, for instance, there is a link that is created between the smell of Drakkar Noir and the person’s neck. Drakkar Noir, from your brain’s point of view, becomes entwined with the memory related to that person, and in turn, that triggers an emotional response. Scent is a powerful and emotional medium, for that reason, and a sense whose effect on people is challenging to put into words.

Nose casts by Saskia Wilson-Brown. Photo: Allison Ramirez. © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved

Tell me about the programs you offer through the Institute for Art and Olfaction.

The IAO’s basic mission is to create access to information and practical knowledge that has heretofore been secretive, one might even say exclusive. We want to bring perfumery to the masses, and hopefully trigger experimental projects that use scent as a valid (and conceptual) art medium. To that end, we have three primary branches of programming (though we’re pretty loose about it):

- Basic access and education through our experimental lab in Chinatown, and through classes.

- Initiating and producing experimental projects that incorporate scent, typically in partnership with artists and institutions such as universities and museums.

- The Art and Olfaction Awards (aka the Golden Pears), which celebrate excellence in experimental, artisan, and independent perfumery on a global scale.

How did you get into educating people about scent?

I started the IAO because I wanted to learn how to make perfume, and I was flummoxed by the lack of opportunities to do so. Moreover, I thought that other people would probably want to learn too, and thought that I would set it up as a non-profit so that we could all learn together, in an affordable, relaxed, and experimental way. I wanted to strip the experience of the heavy marketing language that typically comes with it, and relate perfumery—and scent in general— back to conceptual and eminently human purposes.

I find perfumery fascinating and love the way that scent relates to all aspects of the human experience: from the socio-political, to the conceptual, to the hyper-personal. It’s a really cool field of study, and the IAO aims to create as many points of entry as we can.

Saskia Wilson-Brown with scent vials at the Institute of Art and Olfaction (IAO). Photo: Allison Ramirez. © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved

Learn more about IAO or sign up for one of Saskia’s open sessions here. See a schedule of upcoming courses and workshops at the Getty Center and Villa here.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.