Los Angeles is known as a Hollywood town, but our film scene has always been about more than stars and blockbusters. Throughout the Pacific Standard Time era, experimental cinema screened across town and played a major role in the art scene.

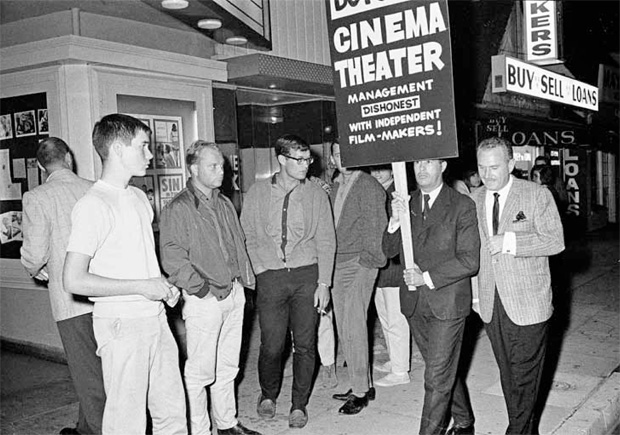

Kenneth Anger (holding sign) and Raymond Rohauer (right) in front of the Cinema Theatre, Los Angeles, 1964. Photo by Charles Brittin (American, 1928–2011). The Getty Research Institute, 2005.M.11. Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, Charles Brittin papers. Courtesy Kenneth Anger

In the early ‘40s, the American Contemporary Gallery in Hollywood was showing everything from silent movies to workers’ education films. Up-and-coming artists mingled with Hollywood big shots and European artists-in-exile. Across town, legions of self-financed filmmakers were concocting experimental films, documentaries, and the beginnings of video art: above the Sunset Strip, at the USC film school dorms, in garages in the Valley.

In the ‘50s, the Coronet Louvre at 366 N. La Cienega became the epicenter of L.A.’s film scene. It featured a mash-up of industry fare with international cinema and experimental works. Young artists came to see films ranging from artworks by European émigrés (Man Ray’s Juliet) to experimental products by young up-and-comers, such as the 20-year-old Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks. And in the foyer was art: Ed Kienholz, for example, organized exhibitions at the Coronet in exchange for doing remodeling work for manager Raymond Rohauer.

Art-house cinemas played a major role in the ‘60s. At the Cinema Theatre on Western, “Movies ’Round Midnight” fused pulp and high art, presenting groundbreaking films with tantalizing names like Flaming Creatures and Dog Star Man, as well as filmic experiments like Andy Warhol’s crowd-displeasing Sleep. There was drama outside the Cinema Theatre as well as in: Kenneth Anger picketed in 1964, accusing the projection booth of stealing a print of his film Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome starring Anaïs Nin and Marjorie Cameron. (See his lone protest at the top of this post.)

Across town movies were also screening in offbeat places, including a converted funeral parlor. The underground cinema of the era was full of nudity and sex, and some venues later became soft core porn houses.

In short, there was a lot to see. “It’s interesting what people had access to then in L.A.: a diverse array of programs from European auteur films to art-house films,” Rani Singh of the Getty Research Institute told me. “This was also a time when there wasn’t a gap between different media,” she said. Artists drew, painted, photographed, performed, sang, filmed—and went to see others doing the same.

Today the same experimental vitality reigns in L.A., both in young artists and in the places that show their work. Los Angeles Filmforum, which has been on the scene since 1975, continues to be a leading programmer of new, independent, and art cinema. In fact, many of the films once seen at experimental spaces like the Coronet are back on the big screen in Filmforum’s series Alternative Projections: Experimental Film in Los Angeles, 1945-1980, running through May.

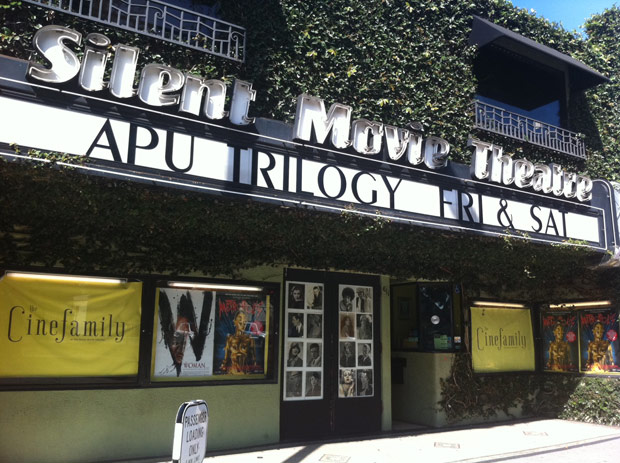

Museum spaces such as LACMA, REDCAT, and the UCLA Film & Television Archive at the Hammer, and alternative venues like KAOS network in Leimert Park and Cinefamily on Fairfax, continue the tradition of mixing the old with the new, the radical with the polished.

Today, one of the hottest spot for experimental film is a place that didn’t even exist until a couple of decades ago: the Web. The Internet has blown open the doors for experimental filmmaking. Production and publishing are under the artist’s control, and the medium doesn’t demand a ticket price or dictate length.

I asked Hadrian Belove, manager of Cinefamily, if the Web has been good for filmmaking. The answer was a big yes. “In the 1950s, if you made your film on 35 mm, it was so expensive, and the cameras were so big, you could make any movie that had a plot and sell it to a market,” Belove told me. “That’s why you have so many movies that are unconscionably bad, like ones where nothing’s happening—just a monster with a hat on—that would play in the movie theater.”

Are today’s experimental movies on the web stranger than previous generations’ experiments? Hadrian thinks so: “Sometimes, I think as the mainstream got more and more interesting, the art had to get weirder and weirder and the ‘niche’ had to be pretty out there.” Take a look at Channel 101, which runs an semi-Hollywood, semi-fringe offbeat alternative awards show, or Show Cave, which screens artists’ videos in Eagle Rock and online.

It’s often been said that L.A. experimental film is so deeply independent precisely because it’s on the edge of Hollywood—in the shadow of the spotlight, as Rani’s essay for the Pacific Standard Time catalogue points out. There’s a lot of freedom in the shadows, now as well as then.

Comments on this post are now closed.