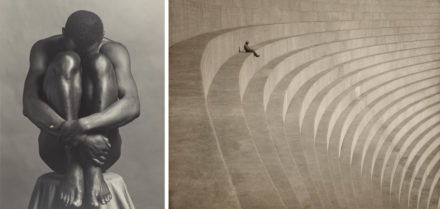

Casemate H667, 2006, Jane and Louise Wilson. Black and white Laser Chrome print. © Jane and Louise Wilson 2006

Bunkers, by their nature, are the peak of architectural strength and impenetrability. Durability is paramount. In the twentieth century the material of choice was concrete, chosen to withstand bombs and bullets and poured as thick as would hold to make a room-sized shield. Like border walls and fortresses, bunkers symbolize political and military might. But unlike architecture meant to protect or champion a “permanent” dynasty, bunkers are built for specific wars or a single front. Their purpose is temporary.

Concrete, however, is not. The concrete bunkers along the northern coast of France, for example, built by the occupying Nazi regime during World War II, have remained on the beach for over 70 years. Hulking and incongruous, they are the subject of the Getty Museum’s photographic installation Sealander, by British artists Jane and Louise Wilson.

The twin sisters, who have made work together since the early 1990s, visited the coastal bunkers in 2006, taking photographs that emphasize the structures’ massive heft and eroded texture, including bullet holes. Some of the bunkers have undergone an eccentric repurposing, such as one that now serves as a white art moderne–esque base of a beach house. Others have been left to decay.

“The ones that intrigued us were the ones that seemed completely obsolete. There was a sense of questions around their functionality,” says Louise, while visiting Los Angeles with her sister for the exhibition. She mentions another project they made about the ruins of the Napoleonic campaign on an island off the coast of Suffolk. There, the structures are sinking into the sand and will eventually be completely erased. She adds, “It’s very sad but also….buildings age and become obsolete.”

The condition of obsolescence, especially around architecture or ideologies thought to be permanent, is one that has long intrigued the Wilsons. To underscore this, their installations, including this rendition of Sealander, often include hand-painted yardsticks, a once-popular unit of measurement now primarily replaced by the metric system.

In France, a discussion is underway about what to do with the long-useless war bunkers, seen by some as a shameful reminder of the nation’s collaboration (through the Vichy government) with the Germans, and by others as vital links to their country’s history. Reflecting on this conundrum, Louise explains her take: “There’s a difference, in my opinion, between conservation and preservation. If you’re preserving the ruin, then you are perhaps looking after it but allowing nature to take its course. If you are conserving it, then you may have to physically remove it from its setting so that it won’t suffer coastal erosion. But to remove it from its setting would take it out of context. And remove our direct connection to the importance of that moment in time, history, and place.”

Sea Eagle, 2006, Jane and Louise Wilson. Black and white Laser Chrome print. © Jane and Louise Wilson 2006

She adds, preserving can be accomplished through photography. The sisters’ images of the bunkers were taken with black and white film using a high-contrast filter. “It seemed too pastoral to have these relics lying on a sandy beach under a blue sky,” notes Louise. “I like black and white because it feels closer to a drawing.” The large-scale photographs loom over the viewer in the gallery, displaying the defunct power of the eroding structures.

Closer to their home, in East London, the Wilsons are witnessing a rapid pace of architectural change. Louise mentions a midcentury Council Housing block near them that is slated to be demolished and replaced with luxury housing. Last year, the condemned building housed members of a local Occupy movement protesting the closure of two women’s refuge centers. “It’s not a terribly fascinating ruin, but it really speaks a lot about obsolescence and the life span of architecture.” She points to British architect Cedric Price, who believed that once buildings have outlived their original purpose, they should either be transformed or demolished—that we should be re-creating rather than fetishizing or conserving the past.

As for local sites of architectural and historic interest, during this trip the Wilson sisters drove down the California coast to visit the San Onofre nuclear generating station, built in the early 1960s. The station, with its huge white containment domes that loom upon the beach, is slated to be dismantled once a safe solution for the radioactive contents has been found. Louise said they were amazed by the danger, post-Fukushima, of placing nuclear material next to the coast in a heavily populated earthquake-prone region. More evidence, as in France, of an ideology’s inevitable expiration.

Noir Mont, 2006, Jane and Louise Wilson. Black and white Laser Chrome print. © Jane and Louise Wilson 2006

Comments on this post are now closed.