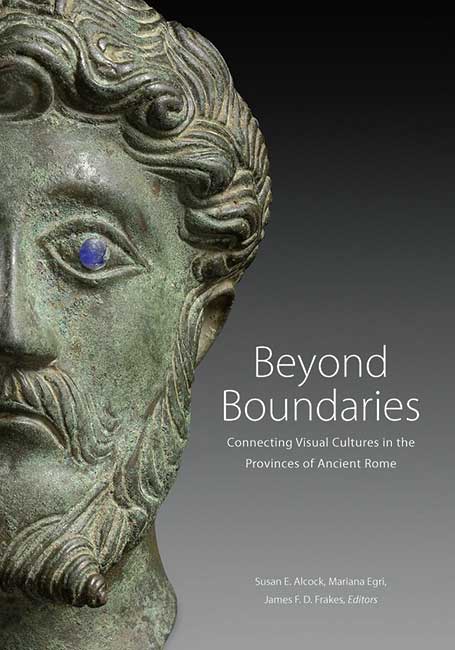

The Roman Empire’s rich and multifaceted visual culture is a manifestation of the sprawling geography of its provinces. In 2011 through the Getty Foundation’s Connecting Art Histories initiative, a group of twenty international scholars began a multi-year research seminar to study, discuss, and ponder the nature and development of art and archaeology in the Roman provinces. Their compelling research resulted in a book titled Beyond Boundaries: Connecting Visual Cultures in the Provinces of Ancient Rome.

Susan Alcock, editor of Beyond Boundaries and professor of classical archaeology and classics at the University of Michigan, Jeffrey Spier, senior curator of antiquities, and Ken Lapatin, curator of antiquities, both at the J. Paul Getty Museum, discuss the impact of the seminar and various essays from the resulting publication.

More to Explore

Beyond Boundaries: Connecting Visual Cultures in the Provinces of Ancient Rome book

Transcript

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

SUSAN ALCOCK: One of the things that we both wanted to do was to break down what is still too often this barrier between art and archeology.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with Susan Alcock, Jeffrey Spier, and Ken Lapatin about the book Beyond Boundaries.

Earlier this year, Getty Publications, the publishing arm of the J. Paul Getty Trust, produced a volume of essays called Beyond Boundaries: Connecting Visual Cultures in the Provinces of Ancient Rome. The book is the result of an international seminar on the arts of Rome’s provinces, funded by the Getty Foundation, and included some twenty contributors from eleven different countries.

The goal of the seminar was to consider the artistic remains of the ancient Roman provinces and how they can complicate and contradict our simple understanding of relations between the imperial center—that is, Rome—and the provincial periphery. To help me understand the results of the seminar, I’ve invited one of its organizers, Susan Alcock, Special Council for Institutional Outreach and professor of archaeology and classics at the University of Michigan, as well as Jeffrey Spier, senior curator of antiquities, and Ken Lapatin, curator of antiquities at the Getty, to select essays from the book, and then lead us through a discussion of the ways that those essays contribute to the book’s theme.

We spoke with Susan over the phone from her office in Ann Arbor.

Sue, good morning. Thank you for joining us, and congratulations on your important co-edited book, Beyond Boundaries.

ALCOCK: No, thank you, Jim. It’s a—it’s a pleasure to be participating in this conversation. And I want to say thank you for giving a shout out to Beyond Boundaries, because it is the product of a—quite a considerable effort on many parts. And in fact, it’s—I’d say it’s the product of a—of a rare combination. We had a genius, [Cuno chuckles] we had adequate support, we had enormous talent, and we had a great scholarly need. And they all sort of came together over, actually, of—over the course, in academic terms, a very long time, over—a more than two-year-long effort. And the book is the result. But it’s the result of a—of quite a long and interesting process.

CUNO: Well, tell us about the seminar itself and how you and your co-convener, Natalie Kampen, conceived of it and then led it through the various places around the world, I take it, to which you took the seminar itself.

ALCOCK: Yes. Well, I guess first and foremost, the Getty was essential to the effort, especially the Connecting Art Histories program, through the Getty Foundation. They are interested, Connecting Art Histories, in locating areas of the world, sort of regions where the study of art history in a sort of a sophisticated and comparative sense is perhaps not as developed as it could be. And they were interested in finding individuals who could be parachuted in there and pull people together and sort of be forced—especially junior people—be forced to confront their assumptions, talk to other people, talk to people they may not normally get a chance to hang out with. And they—the Getty folks had the very great good sense to ask Natalie Kampen to spearhead one of these efforts, looking at the Mediterranean, and more generally, at the arts of the Roman provinces. Natalie was recently retired from Barnard College. At the time, she had moved back to Rhode Island in perilous proximity to where I was, at Brown University at the time, at the Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology. And she sort of said, “Well, would—you know, I’m looking at this; what do you think?” And we sort of decided, you know, we could do it as a team. In part, because one of the things that we both wanted to do was to break down what is still too often this barrier between art and archeology. And Talie was the consummate art historian, and I am certainly not; let’s put it that way. I’m much more a field archeologist by training. So in some ways, just the two of us working together on this project sort of set part of the foundation for what makes it quite innovative and indeed, provocative.

CUNO: And so it began as a seminar. And did you have any hopes that when you began it that it might become a book?

ALCOCK: Yeah, it began as a seminar. We put out a call, we got some twenty or so international cast of characters. Largely junior faculty but with some more senior people leavened in. They came from a variety of fields. There were art historians, archeologist, museum curators, heritage experts; some of them were even, you know, stone Romanists, in a way, but people who knew enough about the Roman Empire to have interesting conversations and to—you know, and to ask those kinds of questions that if you just have, you know, the same-old-same-old usual suspects in a room, don’t get asked. So the seminar was basically designed to disrupt in every possible way, shape, and form. These roughly twenty-odd, two dozen individuals were taken to Britain for about a two-week period, taken to Greece for a two-week period. And basically, small group dynamics, you know? We—you know, we ate, we stayed in the same hotels together, we looked at all sorts of different kinds of pieces of material culture together. We read articles and argued with each other. And the whole point of the exercise was to have enough time to disagree, to put things back together, and to move forward.

CUNO: And how long did the seminar last? Was it extended over different periods of time, so that it was more than a year in duration when it put it all together or—?

ALCOCK: [over Cuno] It was, indeed. In 2011, we went off to Great Britain for about two weeks together. A year later, astonishingly enough, we were able to basically conjoin more or less the same group. And then a year after that in summer 2013 we got together at the Getty Villa for a final wrap-up.

CUNO: And did you communicate [Alcock: I’d say—] with each other in between these trips, so that your ideas were sort of developing in between the trips, and then you would meet together and discuss the ideas that you’d been exchanging by email? I mean, did you stay in touch over the course of that time?

ALCOCK: I’d say we’ve had all sorts of levels of continuing exchange from the get-go right through to now. We have some seminar members who are now currently co-directing fieldwork projects together. We have Facebook friends, we have really interesting and, you know, and international sort of junior colleagues to turn to. You know, to network with, to push the boundaries out, as it were. That’s another reason why Beyond Boundaries is a sort of a fitting title. I think we all felt that, you know, sitting down in a room to talk about something with people from eleven different countries—and not just countries, but different kinds of national training—and to watch the impact of someone who’s come from a fairly traditional—naming no names, naming no institutions—but fairly traditional art historical background sort of sitting down side by side with a kind of a wild-eyed archeologist or someone whose main concern is, you know, heritage in conflict zones. Those are conversations you don’t often get .

CUNO: And you mentioned Talie Kampen and that she was important for the—in the conception of the seminar and its execution. And then we know that she sadly, died before the book itself was published, and the book is dedicated to her. Tell us about the importance of Talie in this project.

ALCOCK: Well, I would describe her as the presiding genius. She was kind of the initial connection to the Getty. She had experimented with this kind of sort of free-range seminar format before. She’d taken some students of her from Columbia to Tunisia, and had seen, you know, the benefit of what happens when you get people out of the classroom, out of the library, make them stand and look at things together, make them move through space together, make them deal with each other in all sorts of academic and non-academic ways. As you know, sadly she became very ill shortly after the project got going. And really, it’s a tribute to the contributors, to all the members of the seminar, that they stayed as focused and as intent on making sure that the best possible product could come out of all this, because it is very much dedicated to Talie Kampen.

CUNO: Now, tell us about the essay that you’ve chosen, why you chose it, and what contributions you think it makes to the seminar, or made to the seminar and makes to the book.

ALCOCK: I chose Susan Walker’s “Celtic Design, Roman Subject: A Portrait of Marcus Aurelius From Rural Britain.” And in part, I chose it because this little Marcus Aurelius—Old Blue Eyes, as we called him—became sort of a mascot through the course of the seminar, the whole seminar. Susan Walker, who is at the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, was one of the more senior scholars who came along on the trip. She was just absolutely invaluable for, you know, just teaching us how to look very carefully at objects. And she sort of mentioned along the way something that was very much on her mind through the course of all this was this kind of strange piece. It’s a—it’s a bronze head. Copper alloy, I should say, not bronze. Susan would be angry with me for that. He’s got very patterned hair. He’s got a beard that is kind of two spiral ice cream cones coming out of his chin. He has his kinda downturned grumpy cat mouth. And he has amazingly startling bright blue eyes. In fact, he looks so—what? Is he a Roman, not—what is this thing? That for a long time, people thought, well, maybe it’s not real. It’s, you know,

CUNO: [over Alcock] What does it date from? What’s the rough date of the sculpture?

ALCOCK: Susan Walker puts it probably after his—the death and deification of Marcus Aurelius in 180 is what she thinks. And this thing is not very big. I mean, that’s one of the—one of the sort of charming things about it. It’s about the height of an of a large oban coffee cup. So there’s—you got this little thing that just packs an enormous visual punch. And it’s a puzzle. Because you know, if you look at it, you say, okay, it’s—it looks like a Roman emperor. But man! You know, those are kinda scary bright blue eyes. And, you know, and it’s so stylized. The beard is odd. What size is it? And it comes from England and—it just doesn’t look like—you know, you think Roman emperor, Marcus Aurelius; I know what that should look like. And he doesn’t look just like he should. That is part of the fun of it and that’s part of the point of this particular chapter. So what Susan does is she talks about Old Blue Eyes, as she calls him, in this piece. But she does it by putting him very much in context or as much context as she can. She talks about the characteristics of Celtic art. You know, it was very colorful, very free-flowing, very not into human or animal representation. And she looks at what happens to Celtic art through its—you know, its history and usage in Roman Britain. And so she’s got this head, which, with the color and the—sort of the free-flowingness of it, and the design of it is clearly Celtic-influenced, though it’s a head of a Roman emperor. And then she puts him into con—into—Marcus into context with other statue heads, but also with jewelry, with cups, various kinds of vessels, including most charmingly, what appear to be these tiny, little souvenirs that people would take home from Hadrian’s Wall. And she basically says, okay, we have this—we have this new sort of representational need, this new artistic need, coming into Roman Britain. We have to show the emperor. And this is what they do with it.

CUNO: So why was it necessary for this strange new set of formal principles and stylistic qualities to appear, why was it necessary to even come up with a sculpture of a—of a face like this? Was it because there was new patronage with the Romans residing in ancient Britain? Or was it because there was an ambition by these new artists, seeing new things brought to ancient Britain from Rome itself, to do things like the Romans were doing them? In other words, did it come from the patron or did it come from the artist?

ALCOCK: You know, that is a great question. And I think one of the things that would come out of this particular chapter is that we’re not entirely sure. And in part, we’re not entirely sure because we don’t’ know enough about where these things were made or how they were used or in what context. And that’s largely because, you know, the examples that we do have, for the most part, don’t have any sort of firm archeological context. You know, if we don’t know the local context for these things, it’s very hard to—you know, to get any kind of authentic story. Now, to be fair, the traditional answer to your question would be, well, because Rome comes in and there’s the imperial cult, and representations of the emperor are essential, expected to—in the practice of the imperial cult. And that’s all very well and good. I think to a point, that’s traditional sort of, you know, Roman art history. Rome demands and the provinces react. Or the core says do this, and the peripheries, you know, suck it up and do it. What I think our book, and what I think Walker’s chapter was trying to do, was to complicate that a little bit and explore, you know, more of the assumptions that—you know, why is that the first question we ask? What did Rome want and what did the provinces have to do in response?

CUNO: Now, Susan Walker makes a point in her essay that these objects that she’s looking at, in her words, “demonstrate a continued taste for Celtic design, a taste for curvilinear, non-naturalistic patterns.” How can we determine that that’s a matter of taste or just a matter of inability to do differently?

ALCOCK: Ah. [laughs] Oh, but they’re so pretty! I mean, you know, no. I think what Walker would say is, you know, that local or sort of indigenous tastes and indigenous stylistic choices endure, but that they can be turned and in—you know, and moved into the realm of things that are new and are different.

CUNO: Well, let me ask Ken to come in on this because he’s done a lot of work on silver hoards in Gaul. So another province of the Roman Empire. And that work shows a provincial style, of course, but a style of extraordinary achievement, a much higher stylistic and formal level of achievement than one sees in provincial Britain. So is this, Ken, a question, can we generalize from one province to another, or the

circumstances are just so different in each? Difference of patronage, difference of materials, difference of talents or something. How do we—how do we take the case of the Celtic design, and then look at Gaul and learn something in the process?

KENNETH LAPATIN: I think, Jim, we can do both. I think as—and we’ll talk about Mladenović’s article, which as Sue says, you know, really addresses these issues of taste and quality head on. And they’re fascinating. But what I think Susan Walker is doing is she’s looking at tradition. And sometimes that has been posed as indigenous identity or resistance. And she doesn’t go that far because she doesn’t believe the evidence is there. But the tradition of non-figural art was very strong in Britain. And so while something like the head of Marcus Aurelius—of which Susan gives a couple examples of similar things, but it’s almost unique; there’re very few pieces of that figural art—aren’t as accomplished, by the standards that we have accepted, from the Renaissance, from Rome, of physical verisimilitude, of stylistic perfection, of naturalism. And so you could say, oh, maybe they weren’t good enough. But if you look at the decorative arts, the patterned arts that Sue illustrates—the Battersea Shield, these souvenir bowls with colorful inlays, with spirals, with rectilinear patterns—they’re extremely accomplished. But they’re practicing a different aesthetic. And so when the locals in Britain were transferring their skills to something figural, representative of the emperor, in response to Rome, either because the order’s coming from the top down or because they wanna generate something to please the masters, they’re not looking at Roman style portraiture; they’re growing it out of their own tradition. So we have these stylized hair patterns, the—what Sue logingly calls the ice cream cone beards, the colored inlays. So we see an amalgam emerging, a hybrid of local taste, local styles, and local skills, with the need to represent something foreign that is being inserted into their world.

CUNO: Now, I think the—Susan Walker talks about a database in the British Museum, of objects which numbers to something like a thousand. So is it sufficient, in your mind, Ken, to allow us to identify local styles within Roman Britain as opposed to just provincial styles, Roman Britain to Imperial Rome?

LAPATIN: That’s a great question, Jim, and I’m not sure. One of the things Susan Walker bemoans is that this database is a text-only database. And the images aren’t yet attached to it. So it gives us the beginnings of approaching this question. But only, I think, by really looking at all of these objects, and also plotting their find spots—many of them are small and portable. Many of them have been found by amateurs with metal detectors. We don’t have their excavated contexts. We don’t know their functions. We might—even when we know where they’re found, we don’t know when they were made, how they were traded. So there’s still a long ways to go to answer these questions.

CUNO: Jeffrey, what do you think?

JEFFREY SPIER: I think it’s a very good topic. I think Susan Walker does make the point—and of course, you could go further—that there is this long tradition in Celtic art of metalwork especially, and inlaid metalwork. And that this skill, this interest survives through probably a very small number of workshops, and then it responds to whatever patronage is there. So the Romans came; well, I need a head of Marcus Aurelius. This is what’s created. And it is in a very good local style, I feel. And she makes the point that this—these workshops survive, I think, until early Anglo-Saxon times, early—beginning of the seventh century. And then your sort of patronage dies out. But it’s a very long tradition.

CUNO: So Sue Alcock, I guess Susan Walker has set the stage for us to consider the relations between the provinces and the periphery and the imperial center, and all the complexity in the periphery itself; that it’s not a single and simple phenomenon, that there are complexities within it. And that allows us to move on to the other essays we want to talk about. But before we do, is there anything you want to say about this particular essay?

ALCOCK: No, except I did choose it because I thought, apart from Marcus being a seminar mascot, I thought that in a very sort of—what could be seen as a sort of a very low-key, quiet kinda case study, Susan Walker’s essay actually really explodes a lot of the things that we wanted exploded. The idea that, you know, all roads lead to Rome. You know, you must be wanting to copy the center. Ya gotta do it in a particular way. That’s—that goes out the window here. The idea that art is like statue heads but things like jewelry are not art, and therefore, we don’t talk to them side by side. She gets rid of that. The very fact we take for granted that, yeah, you want emperors and gods and they’re gonna look human, they’re gonna be recognizable, naturalistic figures—that’s the shock of the new, to many cultures that get pulled into the Roman sphere.

And finally, you know, she just kind of very calmly makes you realize, as your life change[s], your art changes. If your chariots become demilitarized, the idea of decorating them to be terrifying as they race towards you, that’s going to change, too. And there’s just lots of little light touches throughout the whole essay that I really think form a great foundation to certainly, the book as a whole, but especially for the two essays we’ll talk about next.

CUNO: Great. Okay. Jeffrey, you’ve chosen an essay by Jennifer Gates-Foster, which is concerned with the import consumption in the ports of Roman Egypt. Tell us why you chose this essay and what you think that it’s contributions to the seminar are.

SPIER: This is a very ambitious essay. It’s a little more theoretical than the others, because we’re really not talking about art per se. There’s not much art found in these sites. She’s found about the Red Sea ports in Eastern Egypt, of Berenice and Myos Hormos, which were founded in the third century BC under the Greek kings, the Ptolemies. And these have been excavated since, I think, well, the last twenty years or so. And they’ve found very interesting things at these sites.

CUNO: What kind of things did they find?

SPIER: Well, it’s evidence of trade, basically. So—and we’re trying to tie that a bit to the Roman literary references, which say that the Romans were importing huge amounts of especially luxury goods from India and Arabia and everything along the coast there, the coast of Africa.

CUNO: [over Spier] We know that from Pliny, I think.

SPIER: We know it from Pliny, we know it from quite a few other sources, as well, which—you know, you could go into more than is in Jennifer Gates-Foster’s essay. Pliny says there’s 550 million sesterces, which is basically five and a half million gold coins flowing to India every year. It’s an enormous amount of trade. So she’s saying, well, what’s happening at this port? This was the main port to the Red Sea. She uses the theory that—the sort of local theory, that the people there are their own local organization, and they sh—we shouldn’t be looking at it from the point of view of what’s happening in Rome.

CUNO: I think she’s also saying, too, that rather than looking in relation to what happens in Rome and then what happens at the end of the system of trade routes [Spier: Yeah] that leads to India, what happens along the way. Were there distinct cultures along the way? So that as things passed through ports, they took on some of the flavor of the port itself. Is that right?

SPIER: [over Cuno] Yes, exactly right. Exactly right. And the finds from these excavations at Berenice show a huge diversity of cultures there. I think there’re ostraca with graffiti of almost twenty different languages. We—there’s evidence for Tamil-Brahmi community there who must’ve been handling the trade that was coming from India. We have some Ethiopian evidence there. We have other places in India, coins from India.

CUNO: And she makes a bold statement, where she—in pronouncing or just identifying her argument as, “all provincial Roman material culture is local.”

SPIER: Yes, this is the theory. I don’t know how that’s supported in this—in these excavations. I think she’s just trying to concentrate on, who are the people here? You know, these are not Romans, these are native Egyptians and foreigners living in the port, and they have their own lives, and they are making use of some of these imports. And some of the excavation material also shows that things from Egypt—certain foods, certain clothes—were being sent there to the local people, and did not move on, necessarily. I think it’s just a view of trying to imagine, who are these people living here?

CUNO: She raises the term entanglement. This kind of a concept for the engagement that occurs in these sites and things. That seemed to be of significance and rich with possibility for interpretation. Can you tell us more about this idea of entanglement?

SPIER: Yes, I think it’s—again, it’s this idea of, what do you do with this material? I think the best example she cites is, we know that a lot of the trade is for pepper from India. This is very fashionable in Rome, and a huge industry. And of course, it was a huge industry up until modern times, coming from India. And they found, in the Temple of Serapis, in the courtyard, seven and a half kilos of pepper in a pot. And I think you’re wondering, what is it doing there? Is it some kind of a ritual? Is it some kind of a hoard that was being stored or—? But I think she—her position would be, it’s—and correct me if I’m wrong, Sue—I think it’s that this would be for local use. This would be tapping into this trade for the local people who are using the Temple of Serapis in Berenice.

CUNO: Sue, when she—the evidence she uses for this, of course, is what one wouldn’t describe as artistic evidence. There are—there are ceramic pots, within which there are these spices and so forth. But there isn’t much decoration on the pots, so it’s pretty hard to make a case for any kind of artistic exchange. How useful is it, or was it in your conversations with her, and then in the development of the essay, to understand how one can find evidence, and persuasive evidence, of cultural exchange in materials such as the materials she was looking at?

ALCOCK: Oh, this is—this is fascinating to listen to, because in some ways, I think it sort of profoundly is one step to the side of what I think Gates-Foster is trying to say, and indeed, many of the participants in the seminar and in the volume are. And that is, you know, if you’re looking for art, it has to be taken in the entire context of the material culture being used in these local contexts. And if you’re talking about cultural exchange or cultural communication, just looking for decoration on a pot—I’m oversimplifying here, obviously, for the sake of argument—that’s not the only way to see these connections and these influences. And in fact, it’s kind of the focus on art, if—with a capital “A,” if you will, that muddies so much of our understanding of Roman provincial material culture, because we think it’s like, okay, this is art that is created here, essentially tapping off what’s going on in downtown Rome, and sort of what happens in the middle is not all that—all that important.

CUNO: So if these pots filled with peppers come by ship from India, from the coast of India or wherever they might come, and they’re handed off to a trader in the Red Sea port, and then that trader then puts them in other kinds of pots and takes them off to Rome, are we seeing any physical evidence of an exchange of cultural influence, other than the food that’s associated with hot, spicy peppers?

LAPATIN: Well, I think what Gates-Foster is trying to do, Jim, is to ask a very different question, to stop that process and look at what’s going on in the port. Her focus is local. And rather than looking at India and Rome and the transferal of the pepper from India to Rome, to look at what’s going on at this one place as a case study for a series of transactions and interactions that are taking place on a smaller scale throughout the empire as people are interacting and negotiating on the site. And what’s fascinating about these sites is that they preserve, you know, as Jeffrey said, such rich linguistic evidence. There’s also all kinds of imported foodstuffs here on the Egyptian coast—coconuts, rice, mung beans, and other materials. There’s Indian coarse ware, the kind of pottery you’d use for cooking, daily use. So it’s not about art; it’s about people living amongst one another. And this is where the store of pepper is so interesting, ’cause that pepper wasn’t traded on; it was deposited there in a temple. And we don’t know if that’s a temple treasure, ’cause the pepper was incredibly valuable, or it’s something that was less valuable monetarily at this place, closer to its source, than it would’ve been in Rome, and it was kind of taken for local use. Gates-Foster speculates that it could’ve been used for sacrifices, for burning, for local rituals that were a kind of hybrid between the Greco-Roman and the Indian. So what Gates-Foster wants us to do is focus on that local in between. And that’s her entanglement, these entangled communities that are dealing with Romans and Roman traditions, on the one hand, and India on the other, and creating something new in that mingling in the middle.

CUNO: So that in some sense, then, Jeffrey, the two essays set two different questions with regard to how to consider the materials, ones looking at—in the provinces: one from the point of view of relations with the center, one in terms of relations to the local. Right?

SPIER: Yes, that’s exactly right. Where Susan Walker’s very carefully considering the artistic traditions and the relations, I think Gates-Foster is really making us focus on what is happening in a local, non-imperial setting.

LAPATIN: And I would add, what is engendered by this empire-wide trade—whereas in Britain, there was a long tradition prior, and then that continued; here at these ports, they were established, first under the Ptolemies and then the trade expanded greatly under the Romans to facilitate this trade. So we have the center and the periphery creating this new, small, local cultural interaction in the middle.

CUNO: So Ken, you’ve chosen an essay on the creation of a sculptural tradition in the Roman Central Balkans, yet another provincial area of the empire. Tell us why you chose that essay and what contribution you think it makes to our understanding of the art along the borders of the Roman Empire.

LAPATIN: Well, Jim, I kind of surprised myself by choosing this essay, because as you know and as you mentioned, my work has been on Greek and Roman luxury goods—the very high end, the beautiful, the rich gold, silver, gems, bronzes—highly accomplished works that are really greatly admired. But as the seminar’s goal, as Sue said, was to complicate, to contradict, and to disrupt our study, I was struck by this paper when I first heard an oral version of it at the Getty Villa seminar in 2013, and then when I read it. Because it begins with a debate about the role and function of quality, and a debate that Dragana Mladenović had with Talie Kampen, whether quality was a factor even to be considered.

CUNO: Well, tell us a little bit about that debate. What were the parameters of the debate?

LAPATIN: Well, I think I wasn’t there amidst Talie and Dragana, and maybe Sue can jump in with this, but issues of quality have often been viewed as elitist, exclusionary, and really rejecting a large swath of what we would call, either objectively or pejoratively, provincial art. And what Dragana Mladenović does in this essay, which I found so satisfying, is she addresses this head on, really on two levels. One, the theoretical and methodological, why quality matters. Not to judge art worthwhile, but to understand it in its historical context. And she’s looking specifically at the sculptural production of the province of Moesia Superior, which is modern day Serbia and Northern Bulgaria, where the sculpture is really bad.

CUNO: [laughs] Tell us a little bit, before we go farther with the sculpture, about the port or the region, Moesia. Tell us about its character and its history and its relationship to the center Roman center.

LAPATIN: Well, it’s on the shores of the Danube in the Central Balkans. And it was conquered rather late by the Romans. There were tribes there. And the artistic traditions were aniconic, non-figural. And there wasn’t—it wasn’t a rich province, and there wasn’t a longstanding art tradition. And so one of the things Mladenović looks at is how to create, especially sculpture, you need a number of things. You need high quality stone, which really doesn’t exist locally. You need long traditions of apprenticeship and training, which can’t just be imported overnight. And you need a class of patrons who value these things. And so while some of the naïve features of the local production—frontality, linearity, distorted perspective, simple symmetry—these things have been viewed as features of local identity, or even resistance to the center, Mladenović argues quite convincingly, in my view, that these are really the products of inexperienced carvers who haven’t yet attained the skills—which take generations of constant iteration and training, and masters training apprentices—to do these things, to sculpt a human figure realistically in three dimensions. And these skills just didn’t arrive, and really never arrived, to the province. But rather than just leaving this material out of the study because it’s not as good as what’s done in Rome, Mladenović explores the implications for the attempts to mimic some of the Roman forms. And she talks about, in her section headings which I love—you know, “Understanding the Bad,” or “Why Not Any Better?”—what is good enough? Getting some of the form, having it recognizable, serving the function. But there wasn’t the desire, she argues, to be exactly verisimilitudinous, to have the wonderful naturalistic flowing draperies, to get that individualism. Rather, to create something that fit in a slot that answered the need of the local patrons. So she argues that the art is, in a way, balanced between what we saw in the strictly local of Jennifer Gates-Foster’s essay, and the real larger negotiation of Walker’s.

CUNO: Do we know enough about the local culture to say that it was resistant to the demands of the imperial center of the Romans who were there? Or that it simply wasn’t capable of doing it? I mean, the sense that they hadn’t got the kind of training that was needed.

LAPATIN: [over Cuno] Well, this is the—this is the key thesis of this essay. Mladenović says that because these physical features of the objects, which we can or might not wanna call artworks, because of their poor quality— they have more in common with the work of inexperienced carvers than carvers exerting a local tradition. Because unlike in Britain, where there was a different tradition that was adapted to Rome, here there was almost no tradition and the production is very small.

CUNO: Does that mean, then, that the local tradition that existed just simply didn’t value verisimilitude, as you say?

LAPATIN: [over Cuno] Exactly.

CUNO: Right. And do we know any set of sort of the religious practices or the kind of philosophical positions they took, to know that this fit into a worldview of theirs?

LAPATIN: We don’t. I think—but we have come in the West to accept realistic, figural, portrait-like art as a norm. And we get that from the Greeks and Romans through the Renaissance. But that really isn’t the norm in many, many cultures. And especially in the Central Balkans, there was not that tradition. And in the few instances where they’re trying to imitate or create something along those lines, they’re not achieving the high level of skill, because they don’t have the experience to do so.

CUNO: Well, let me ask it this way to Jeffrey. I’m the product of a military father. I know what a military culture is like. So is this case, that the military culture that was there representing Rome was itself not interested in fine things? That in other words, they’d be perfectly happy with mediocre things as well because that was part of the hustle and bustle of a military culture?

SPIER: Well, I like that question. But I think—I think it’s—that’s not the answer to it. I think the answer is, they still were—I think Ken is right, that we’re talking about a culture here that does not have this tradition of figural representation. So when you do see it here as Mladenović shows, it’s really for the new patrons, when they want someone—they want some prestige—

CUNO: [over Spier] And these patrons are Roman patrons, or local patrons?

LAPATIN: [over Cuno] I think they’re Ro—well, we don’t always know. Some of them are Roman; they have Roman names, anyway. But either Roman or local who are affecting Roman tastes. They want to show that they are Romans, so they’re using the local artists and coming up with these stele and portraits in sort of a pseudo-Roman style. And they’re happy with that.

CUNO: What was the Roman culture like there? In other words, when—because this is now post of the empire. So was it filled with the most, you know, elevated personalities? Or was it a brutal [Spier: Well—] imposition of a military rule?

SPIER: No, I think there are Romans there. And going back to the military that you raise, this is on the Danube, so we do have a lot of military officers here. But I want to make the point about that, that the other thing we’re seeing—she touches on it here—we do have military— we do have workshops traveling with the emperor or with high military officials, making things in this area. And these do tend to be very good quality. Some of the things that Ken has worked on—silver, jewelry, you know, gold that was given to military officers. We have silver plates stamped with the name of Sirmium in Serbia. And the mints also were traveling. This is generally quite late. This is in the later third and fourth century. And the—and the piece that she—Mladenović shows at the very end of this essay, this remarkable pilaster from the imperial palace at Gamzigrad is in the local style. But the other things from this palace are very good. There’s a porphyry head of the emperor from the same site, which was clearly an import. But they were bringing things they felt were more appropriate, at least or these higher-level officers, and even the imperial court.

ALCOCK: Jeffrey, I’m just so sorry that you weren’t with us for the seminar, because we would’ve had some fantastic arguments about calling something like, “pseudo-Roman style.” [Spier laughs] You know, I don’t think the participants—or most of us, anyway, in the seminar—can even wrap our heads around what you mean by that. And also, there’s the, you know, the stuff in that’s “very good,” I mean, “very good” in what sense, is the question.

SPIER: [over Alcock; inaudible] In Mladenović’s sense, there is a quality of art. And if you look at the pilaster with tetrarchic heads, [Alcock: Mm-hm] that’s certainly copying something else.

ALCOCK: I don’t know if she’d say that’s very good or she said that is—that is well crafted or that is—

SPIER: Well, quality.

ALCOCK: [over Spier] I mean, it’s—this is a slippery vocabulary [Spier: True] here, is I guess, what I’m saying.

SPIER: [over Alcock] And that, too— and that’s the reason, I think, why the question of quality has been recently, you know, pushed aside. And for me, [Alcock: Yeah] I thought it was great the way Mladenović comes out at the beginning and at the end saying that quality, which has been the determinating factor for the construction of the art historical canon is not equal to historical importance. And by looking at these carvings that are—we can call them unskilled, we can call them naïve; she calls them bad—we can still learn a lot about what’s going on in the culture and the interaction. But we have to address why the quality is what it is or isn’t. And there are the conscious choices that skilled artists like Picasso or, I think, some late Antique/early Christian carvers make, or even early Greek carvers. If they could carve ears on kouroi that looked like seashells, it’s not because they can’t carve a realistic ear; it’s because they choose not to. But in this case, Mladenović argues convincingly that the naïveté, the poor-quality material, the lack of tradition, the lack of patronage, the lack of masters to teach indicates that these aren’t conscious choices; these are attempts to do something maybe better; or maybe this is just good enough. And the better is, I think, quite traditionally defined as, you know, mimesis, as realism that mimics the world. And that was a very high expectation in Rome. And Mladenović’s point here is: that didn’t transfer. Maybe some of the forms did, of having a stele, having a wreath, having a bust carved on a stele that could be recognizable. But having something individualized and convincingly realistic wasn’t a value. And that tells us something about what’s going on locally, what was taken onboard to satisfy needs of status, prestige, fulfillment in a Roman model. But they didn’t take the whole package. And they couldn’t create the whole package ’cause they didn’t have the skills, so it was good enough.

CUNO: Okay, I’m afraid I’m gonna have to bring the conversation to a close. But Sue, I wanna ask a last question to you. You know, we’ve looked at these three case studies—Celtic Britain, Red Sea Ports, Central Balkans—where they’ve raised different questions. We’ve answered these questions in different ways, even among the few of us here around the table and you in Ann Arbor. But it has been a dynamic conversation, I think. And I wondered if the conversation this morning alone has confirmed your highest hopes for the seminar and the book, that perhaps it raises additional questions that you and the members of the seminar will continue to consider, as you discuss among yourselves the role of the center and the periphery in the understanding of Roman art. How has this conversation sort of met your standards, as you anticipated the seminar to have an afterlife? What is the afterlife of the seminar and the book? And are you pleased with what you’ve heard today and what you’ve been hearing since the book has been published?

ALCOCK: I think this conversation—and I was serious when I said to Jeffery, “You should’ve been with us.” Because I think the conversations that—the arguments, the what-exactly-do-you-mean-by-that sorts of follow-ups—they started on day one with the seminar, and they’re continuing to run now, through this podcast. I think the book will have legs. I think it has a diversity of case studies, a diversity of kind of methodological and theoretical approaches. I think it will annoy a lot of people. And I think that’s just fantastic.

CUNO: So Sue, thank you for the leadership you provided the seminar itself, the leadership you provide the book and its publication. Thank you for your contributions this morning. And Jeffrey Spier and Ken Lapatin, here at the Getty, thank you for joining us in what was a lively, lively conversation.

Our theme music comes from “The Dharma at Big Sur,” composed by John Adams for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. It is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday. Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, and SoundCloud or visit getty.edu/podcasts for more resources. Thanks for listening.

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

SUSAN ALCOCK: One of the things that we both wanted to do was to break down what is still too of...

Music Credits

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.