The nude human figure, both male and female, has been central to European art for centuries. During the Renaissance of the 1400s and 1500s, artists across Europe used the nude to explore religion, nature, human relationships, and beauty itself. But artists’ approach to the nude were not monolithic, nor were these works received without considerable controversy. Although created long ago, these works continue to inform contemporary attitudes toward the nude human figure in art.

The exhibition The Renaissance Nude, on view first at the Getty before moving to the Royal Academy in London, explores the development and deployment of the naturalistic nude, as well as the contexts in which these works were created and received. In this episode, curator Thomas Kren discusses this incredible exhibition.

More to Explore

The Renaissance Nude Catalogue

The Renaissance Nude Exhibition Information

Transcript

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

THOMAS KREN: The nude actually made people uncomfortable in the Renaissance. It certainly provoked controversy. And in a way, the discomfort with the nude body, especially within a Christian culture, isn’t so different from the way in which the nude can make people uncomfortable today.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with curator Thomas Kren about his new exhibition The Renaissance Nude.

Ever since the Renaissance of the 1400s and 1500s, the nude has been one of the defining features of art in Europe. And yet, artists’ and viewers’ attitudes toward the nude were as varied and complex centuries ago as they are today. The exhibition The Renaissance Nude, on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum from October 30 to January 27, explores this theme. It traces the gradual emergence of the naturalistic nude and its rise to artistic prominence over the course of more than a century and explores the different ways nudes appeared in art, how and where they were displayed, and how people reacted to them.

I spoke about the exhibition with its curator, the Getty Museum’s Senior Curator Emeritus Thomas Kren, first in our recording studio and then in the exhibition galleries. I have to say that they exhibition is one of the most beautiful exhibitions I have ever seen, and equally one of the most challenging.

Following its presentation in Los Angeles it will be on view at the Royal Academy of Arts in London from February 26 to June 2, 2019.

Well, Tom, thanks so much more this time on the podcast, talking about this exhibition, The Renaissance Nude, which is extraordinary in the quality of works that you’ve been able to gather together for it. One might’ve thought that the Renaissance nude was so well known as a topic of exhibition and book that there was nothing more to say about it. But you’ve found a lot more to say about it. What got you started on this project, and why an exhibition?

KREN: Right. And thank you very much. Well, actually, the subject is indeed well known and certainly much studied. In the world of art history, the body has been one of the great themes of scholarship of the last generation, certainly. But interestingly, and even surprisingly perhaps, it’s never really been the topic of an exhibition that tries to be comprehensive, or at least have a broad reach.

So as one of the greatest themes of Renaissance art, I mean, it just seemed that you could potentially put together an exhibition of unrivaled beauty, just by bringing together many great examples. But we tried to do something more than just that. Kenneth Clark’s is something that we were all raised on, especially old-timers like me, certainly.

CUNO: Called The Nude.

KREN: Called The Nude, right. Kenneth Clark has quite taken a beating in probably the last thirty years in scholarship. Up to a point, for good reason. But the thing about the Clark approach is it’s really much more sort of formalistic and aesthetic. And of course, we’re interested in these works because of their great beauty and visual interest.

But the academic literature of the past three decades really tried to look beyond sort of a traditional sort of formal view of art and the great formal achievements of the Renaissance, at the cultural context, at the meanings of the works in their own time.

And one of the things I think that’s interesting about this is, the more we looked at this and thought about it, is that the nude actually made people uncomfortable in the Renaissance. Or it certainly made some people uncomfortable in the Renaissance. It certainly provoked controversy. And in a way, the discomfort with the nude body, especially within a Christian culture, isn’t so different— I mean, it’s not the same, I admit, but it’s not so different from the way in which the nude can make people uncomfortable today.

So we felt that the Renaissance nude was actually a subject that was very relevant, very current, if you like, in that it can provide a kinda mirror into our own values or let us think more about issues that we’re facing today, dealing with gender or sexuality, and even religion.

CUNO: And you made a point, in your essay introducing the exhibition catalog, to point out that you’ve brought different interpretative perspectives onto the topic of the subject of the nude itself, including sexuality and gender studies and queer studies and various kinds of things. Did you have a difficulty bringing them together in the exhibition? ’Cause the exhibition is very different than the book itself; you get more latitude in a book to sort of make these points.

KREN: Yeah, good question. We did try to get leading voices who were dealing with especially issues of gender, sexuality, queer theory, and so on. I think there are a range of cultural perspectives brought to bear in the catalog. And hopefully, it comes through in the show, as well. The show is actually organized to the best of our ability, sort of following the catalog and following those themes. The biggest challenge actually came in the fact that there was a lot of really interesting historical data and narratives around certain objects and certain responses to objects that were quite intriguing, where in the context of an exhibition, your labels can only be so long and you can only say so much. So there definitely were limitations that we came up against.

CUNO: And we talked about this a little bit before we started on the podcast about the current climate, with regard to the exploitation of the female nude. I know that one of the authors in the catalog, Jill Burke, who’s a professor at Edinburgh, has responded to some of these questions regarding the content of the exhibition—that is, the place of the nude as it’s seen today. And she said something about a fifteenth century scholar, Manual Manuel Chrysoloras.

KREN: Chrysoloras, yeah.

CUNO: Who argued, she says, that even though looking at real naked bodies is licentious and base, viewers are not admiring the bodies themselves, but the mind of their maker.

KREN: Right. That’s actually a very, very good point because in a sense, I think really up until the modern era, the appreciation of the nude has been rationalized on that basis, that we’re looking at the genius of the artist, his craft, his special gifts and skill, and the way to elevate beauty to the highest plane. And in fact, we continue to admire these works for their extraordinary beauty; but we also see them as potentially provoking a broader range of reactions.

I think that we are in a moment where I think everyone is prepared to sort of look at some of the subject matter of Renaissance art more honestly, and acknowledge that in fact, the narratives weren’t always flattering to their patrons or, certainly not to women.

I mean, some people will look at some of the female nudes and say that these are paintings that objectify women. And we’re not necessarily disputing that. But we’re trying to explain what the historical context of that is, and trying to explain what the attitudes were there and trying to explain what’s going on in the image, so that people can judge for themselves. And also I think, hopefully, get a sense of attitudes today that are considered problematic, you know, have historical roots, and that the Renaissance period is one of those periods.

CUNO: The subject matter of these objects depends on a kind of intimate relationship to the object itself, in many cases. For example, in your first essay in the catalog, you explore the metaphor of Christ as a bridegroom. And you talk about the role of that image in the mystical experiences of nuns, monks, and laywomen. In other words, the body of Christ was something that one needed to engage with intimately.

KREN: Actually, I think you’ve got to the core of it. Which is that in devotional practices of the fourteenth and fifteenth century, in particular, where the church was trying to foster more structured prayer and more direct prayer to Christ and the saints, there’s an attempt to encourage a more intimate experience. There’s a vast devotional literature that encourages the private devout person to experience Christ’s sacrifice and character as human; his divine character if you like.

And so this was encouraged through prayer and through narrative and through text, but also through images. And one of the things that I’m sort of positing in the essay is that this attitude, this desire for a more immediate experience of Christ—and especially for the human Christ, the Christ who came to earth and was crucified on the cross and resurrected—to experience him as a more physical being, as a more immediate being, may have encouraged artists themselves to try to create images that corresponded with— more with one’s experience of human bodies. In other words, creating more naturalistic images. That in itself, it wasn’t merely the revival of the Antique, revival of Classicism—although that’s very important and it plays a significant role in the show—but there were other cultural impetuses for more naturalistic, more real, more central images of Christ and the saints.

CUNO: You point out the relationship between the depictions of the nude body of Christ and the devout yearning for this immediate experience of Christ’s humanity, as we’ve just described. How was that expressed differently in the north of Europe from the south of Europe? Let’s say in the Netherlands or France and Italy.

KREN: Certainly, some of the literature, like Thomas à Kempis, some of the devotional literature that was read was actually read in the north and the south. And I would say that there were different sects that were promoting these kinds of attitudes in the north and the south.

And one of the things that I think that these devotional practices shared is these kinds of devotional images, they were particularly popular in the north, but they also were found in the south, as well. And actually, one of the points of the show was to argue that in fact the nude was a European phenomenon; that although probably its boldest and most original manifestations were in Italy, in fact very important and separate manifestations of it are found throughout Europe.

CUNO: So in your essay that introduces the catalog, you’ve presented us with a range of types of objects that we might see in the exhibition. Also the kind of contexts, literary and spiritual contexts in which they might be undertaken or have been seen at the time.

When we go into the exhibition and into that first gallery of the exhibition, have you installed it in such a way as to introduce these themes?

KREN: We actually start with an image of Adam and Eve, because the narrative of Adam and Eve introduces an issue that’s fundamental for the show. Which is that once Eve took a bite of the apple, one of the first things that happened is she and Adam become aware of their nakedness, and they immediately try to cover themselves. And this notion of shame over the body, over the unclothed body, sort of initiates at that moment.

And that discomfort with nudity is a kinda subtext of the show throughout. That even though this is a show about the triumph of the nude, that in fact, there’s always that sort of subtext of complication in attitudes towards the body, in Christian attitudes towards the body, in what was then certainly largely a Christian culture.

And the other point of that first section on Christianity is simply to show the extraordinary way in which the new ideas about the body were transforming the way Christian subjects were presented. And so that in fact, Christianity’s a really important part of that narrative.

CUNO: Now, to tell this story, which is so large and complex, and so dependent on the right objects, there’s bound to be a number of objects that you wanted to get that you couldn’t get because they were too rare, too big, too valuable, whatever it might be. What objects were you unable to get that you wanted most to have in the exhibition?

KREN: Well, someone did say to me that if you can’t get Michelangelo’s David, why bother? And in fact, we knew we couldn’t get Michelangelo’s David. But one of the things we felt from the beginning was that the subject was so incredibly rich. There were so many great works by great artists, and so many great works by artists who were much less well-known, that to provide a kind of overview of the range of achievement, and even the diversity of nudes—

One of the points of our show was that whereas the Renaissance nude is often considered to be about the notion of the ideal body, there were actually many ideals of the perfect body. There were many kinds of bodies that were being represented in this. And we did feel that we could get sufficient number of high-quality works to represent that breadth.

CUNO: Well Thom, let’s go and take a look at the exhibition.

So Thom, thanks for meeting with in the galleries of the exhibition The Renaissance Nude. It’s a triumph of all kinds, and I hope you’re pleased.

KREN: I’m absolutely thrilled. And especially when you’ve spent a long time conceptualizing a show and thinking in terms of abstracts and reproductions, and then suddenly it’s all together in the galleries. It’s a revelation for me.

CUNO: That’s actually a good place for us to start in this conversation. And that is, how it is you put the exhibition together. Because our podcast listeners maybe don’t realize the extent to which these things are difficult to get together. You have to request the loans from public collections around the world and you have to secure the loan from them and bring them here. Then you have to mount them and put them up, and then you have to write a catalog around it. When does it all begin?

KREN: Well, we started working this show actually quite a long time ago, almost five years ago. And with a couple of my research assistants, Thomas de Pasquale and Andrea Herrera, we started putting together a checklist that would tell the story that we wanted to tell. Which was that the Renaissance nude is much more than about the things one thinks of most obviously, which would be the work of Michelangelo, or Raphael, or Leonardo, or even Albrecht Dürer.

But because the nude was a subject that was embraced by many, many artists across Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, we wanted to tell that broader and wider story. There are about, well, shall I say roughly forty-five lenders. In fact, we talked to even more lenders than that, because not every prospective lender was able to follow through.

CUNO: Well, it’s paid off enormously, when you see the loans and quality of pictures and sculptures and prints and drawings that comprise the exhibition. Now, you began to think about this, I think you said, five years ago or so. And was that prompted by some dissatisfaction with the way the nude had been treated in other exhibitions or in other publications?

KREN: Actually it’s an interesting question. Certainly, there has never been a synthetic account of the European nude during the Renaissance.

CUNO: Well, you and your fellow essayists in the catalog clearly were interested in different modes of interpretation to be brought to bear on the nude itself as a question. Was that something that you had in mind in developing the exhibition from the start, that it was gonna be looking at the nude in ways that other exhibitions and publications hadn’t?

KREN: Yeah, I think actually it was very, very important to have a range of perspectives. In the past generation, there’s been a tremendous amount of research on the body, from a variety of perspectives—of queer theory, gender theory, and so on—that have actually really allowed us to see these works in quite a different light.

So we’ve tried to represent some of those viewpoints in the catalog to give a fairly rounded view of approaches to the subject.

CUNO: Yeah, that’s very apparent in the catalog of the exhibition. How is it possible, and how apparent is it, in the experience of the exhibition when you walk around the galleries?

KREN: To tell the story, we’ve tried a particular structure. There’re five central chapters, on Christianity, Humanism, what we call the Abject Nude or Beyond the Ideal Nude, Artistic Theory and Practice, and then a section called Personalizing the Nude.

But within those sections, we have grouped things with subthemes. Like in the Christianity section, there’s a section on Saint Sebastian and Bathsheba, which were important subjects in the second half of the fifteenth century; or on the body of Christ; always trying to group together works from different parts of Europe—often from Italy and Flanders, or Italy and Germany, or even a mix—to try to show the ways in which there were these kinds of parallel developments.

CUNO: You begin the exhibition with Adam and Eve, which is a expected image to start an exhibition about the Renaissance nude and the place of the Christian story in the formation or the development of the Renaissance nude. But just a few feet away from that initial painting is a illuminated image of Bathsheba bathing, by Jean Bourdichon, of the late fifteenth century. It just makes the point that you were from the very beginning, complicating our notion of the nude; that it wasn’t something going to be looking at the stylistic development of the nude over the course of the fifteenth into the sixteenth century; but immediately, it was going to be a complicated contextual presentation of the nude.

KREN: Right, exactly. And in fact, this image in a way this miniature is the one that actually piqued my interest in the whole problem, because it is this image of a fully nude Bathsheba. You can even see her exposed genitals under the water. The figure is a siren, who, according to Christian theology, was the seducer of King David, who’s shown in the background.

And I remember actually when I was the curator of manuscripts, we purchased this miniature, and I kept puzzling over the fact that an image so sensuous could be in a book of hours, in which the rest of the imagery are things like the annunciation, the crucifixion, images of other holy figures engaged in pious acts. And this image seemed so erotic. I couldn’t quite parse how it fit in with this very, very devout context.

And eventually, my research showed that in fact, these kinds of images had grown very popular at a certain point. The most erotic ones seemed to be in books of hours made for men. And often in books of hours made for women, the Bathsheba subject wasn’t even to be found, or it was treated in a very different way that deemphasized this sort of blatant eroticism. So it became clear that this image really had more than a pious function.

CUNO: Well, the image is, as the story tells us, Bathsheba being spied upon. So we see the man spying upon her from a distance, which is a kind of poetic equivalence for ourselves looking at the image and looking at her in the image.

KREN: I think that’s very much the point; that this was made for a male viewer, actually the the King of France. And where she has this kind of sidelong glance, where she seems to be looking back at David, her body is clearly displayed for the viewer to see and to take in. It does appear to me to be an image designed to delectation.

CUNO: You’ve paired it with Saint Sebastian by the same artist, Jean Bourdichon. Tell us about this and why you paired the two together.

KREN: So we’re being a little bit provocative here because these books represent a book of hours made for a king, Louis XII, and a queen, Anne of Brittany, the bride of Louis XII, both painted by the same artist. Very similar kinds of books, with very similar scale and very similar kind of decoration. But one of the differences is the king’s book has this rather luscious image of a seductive Bathsheba, which the queen’s book lacks.

But the queen’s book has several images of rather sensual figures of male nudes, including a Saint Sebastian, who at that moment in Italy, was probably the preeminent subject for the male nude. And there are a couple of other miniatures of male nudes in this book, which otherwise is full of pious images. And we know that Anne of Brittany was a very pious queen. But at the same time, one has to wonder, what is the role of this kind of image in a prayer book like this? It almost seems like a kind of response to the Bathsheba images that appeared in the men’s books, in my view.

CUNO: We should make it clear to our podcast listeners that Saint Sebastian is not entirely nude.

KREN: Right, exactly.

CUNO: Why is there a kind of a modesty about that?

KREN: My sense is the mores differed from region to region in Italy; but generally, you could say that covering the genitals, genital modesty, if you like, was expected in almost all arenas. And in a way, that’s what makes the image of the Bathsheba so shocking and so out of the norm.

Because the artist has troubled to include them. But the image made for a man, in fact, is simply more overt. And that, in a sense, reflects certain gender values and hierarchies at that time.

CUNO: Well, there is in the exhibition, a number of paintings, a number of works of art that raise questions about the nude. Let’s look at this extraordinary painting by Hans Baldung Grien, the German painter, from about 1523, which shows these two female nudes, a fiery setting in the background. They’re described as witches. Because it’s one of the strangest paintings of the period, and I think one of the strangest paintings of any period that I’ve ever seen.

It shows these witches against a pale yellow background, flames billowing from the back, or one woman holding a glass jar in her left hand, and in some conversation with a woman opposite her.

KREN: Actually, I would say that this is certainly one of the most disturbing paintings in the exhibition. It is a depiction of witches. Witches were thought to be able to conjure inclement weather, tempests and storms. And that seems to be what’s happening here. There is a storm sort of rising up above the horizon, about to actually envelop the figures themselves. They clearly are represented as kinds of sirens, fully nude, voluptuous, and one of them sorta looking seductively over her shoulder, back at the viewer.

And in fact, Baldung made a specialty of depictions of witches of this kind. Very sensuous images, very voluptuous images, often engaged in very sort of bizarre eroticized behavior. And the context for it is that in fact, this was the beginning of a period in Alsace—and Baldung was making these works in Strasbourg, which is in Alsace, which really became one of the centers of the witch craze.

I think the number’s around 5,000 women who actually died there. So these are actually images that really demonize women. It should be said that most of the witches were thought to be women, and it reveals a whole social attitude towards both women and their sexuality.

CUNO: Is there any reason why witches would be portrayed nude?

KREN: Clearly, the point of this nudity is that they are very sexual beings. To eroticize them, to show that in fact, part of their diabolical activity is based on this very sexual quality.

CUNO: Well the painting that we’ve just been talking about is set within the context of a gallery which has nude figures in a landscape. What is the relationship between the Baldung Grien picture to the other pictures? And what is the importance of the concept of the nude in the landscape?

KREN: One thing that we found most interesting was the way in which there were developments across Europe that were contemporaneous, but in many ways quite distinct. And what we’ve tried to do here is show a group of German works next to a group of Italian works, all of which feature nudes in the landscape.

And in the Italian tradition—in the great Dosso, for example, or in the Perugino next to it—you have luscious nude figures in these incredibly verdant, pastoral kind of landscapes. And they’re subjects that were inspired by pastoral literature, specifically Classical pastoral literature that— In the case of the Dosso, you have a figure that has the satyr Pan lusting after the beautiful nymph reclining in the foreground. In the smaller picture by Perugino, you have the god Apollo with the figure of the shepherd Daphnus, with whom he is enamored, again set in a very beautiful, very poetic landscape setting.

It became a fundamental theme of Renaissance art. At the same time in Germany, the landscape was also incredibly important for figures that involve the nude. One of the great examples is the Cranach painting, which shows a specifically kind of German forested landscape. And it turns out that actually, one of the great key developments for Renaissance Humanism in Germany was the rediscovery of Tacitus texts on Germania. This is a great Classical writer. Among other things, he extolls the particular character of German landscape. So actually fairly quickly, we find that incorporated in these themes.

CUNO: And here, this is an engraving of a female figure, a nude figure, lying on her side in the midst of a landscape. It’s an opportunity, it would seem, for the artist to make just a beautiful thing, and for that beautiful thing to be made available in small personal format. That is, the size of a print, about four inches by five or six inches.

KREN: Yeah, exactly, exactly. And actually, one of the things actually that’s very significant, or the point that the show tries to make, is that part of the success of the nude, or if you like, the triumph of the nude in the Renaissance is very much sort of facilitated by these new medias, such as the illustrated printed book or printmaking. So clearly, there was a demand, still within a relatively elite circle, for this kind of imagery.

We don’t know exactly what the meaning of this is. This is the beginning of the period of the sort of reclining Venus subjects. We don’t actually know that this is a Venus for certain. But it certainly is related to that genre of the reclining female nude in the landscape, which is essentially a new genre at the beginning of the sixteenth century. So this is the beginning of a moment where this becomes actually one of the great subjects in European art.

CUNO: Because it allows for a certain idealization of the human form, and a kind of perfection of the human form?

KREN: It certainly is very much about the beauty of women, which in itself wasn’t just a passing interest, but something that was discussed and debated among intellectuals, the desire for images of beautiful women, drawing themselves on notions from Classical literature and the understanding of Classical art.

CUNO: So we’ve talked about three galleries worth of images in this brief presentation. How is the exhibition developed to this point?

KREN: The exhibition starts with the Christian narrative, because the Christian culture permeated the most corners of Europe, and probably was responsible for the largest number of imagery that actually reflects these new ideas about the nude and the depiction of the nude.

The second section, the one were in now, on Humanism and the Classical revival, is where many people often begin the narrative. It is incredibly important for our understanding of the nude and for ideas about the nude, and it introduces the greatest variety of new subject matter. But we thought it was actually important to kind of nestle Humanist ideas within the Christian context, because in fact, that sets up some of the conflicts and debates around the nude that would rage then, and even continue to exist down to the present day.

CUNO: And from the very beginning you’ve mixed Southern and Northern, that is you’ve mixed low country, Belgian, with Italian painting.

KREN: That’s correct, exactly.

CUNO: What is the relationship between the north and south of Europe and the transmission of the nude figure from one to the other?

KREN: Well, in the traditional accounts of the origins of the nude in the Renaissance, the focus has largely been on the importance of the artistic invention in Italy, of the role of Michelangelo, Leonardo, or Raphael, and even artists before them, and their tremendous influence outside of Italy. But in recent years, scholars have found more and more evidence of the ways in which the Italians actually were looking at northern European artists. So that in a way, it was an influence that went in both directions.

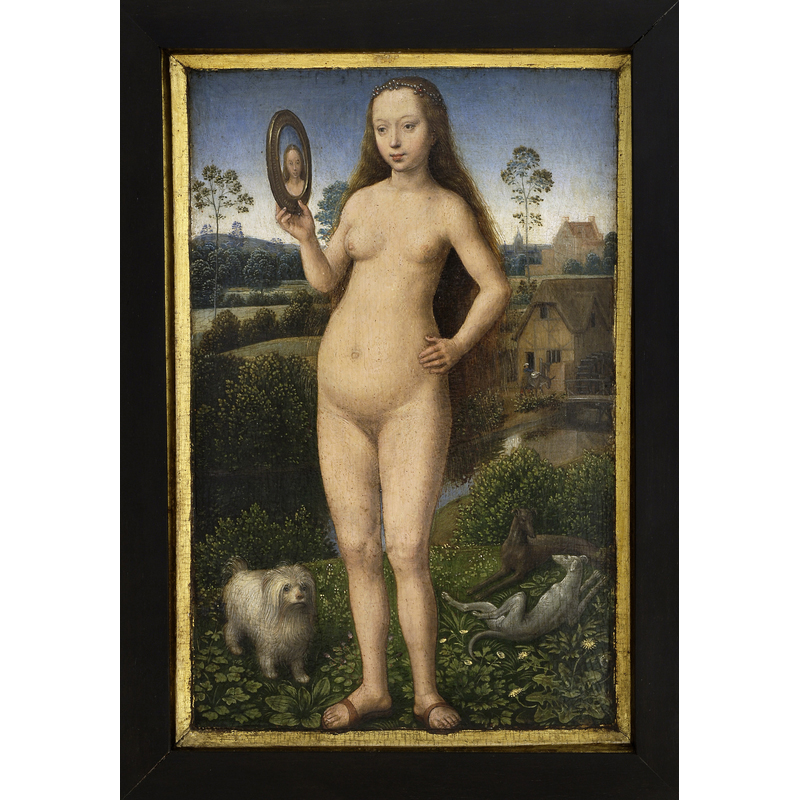

Nudes by Rogier van der Weyden and Jan van Eyck and other Fleming artists were being collected actually in Italy. And another example actually in the exhibition is this wonderful little triptych by Memling, actually a very iconographically very unusual triptych which clearly was intended for private devotion.

But rather than having as a subject, the Virgin and Child or the crucifixion, actually has an image of Luxuria, this fully nude woman who’s looking in the mirror, admiring her own beauty—which, it should be said, is considerable—standing in a landscape, but surrounded by other images of hell and death itself. A moralizing context, if you like, for the image, reminding the viewer that the consequences of lust, of desiring this woman, were in fact, severe.

And we’ve done something a little bit unusual here. We are evoking the great art historian Kenneth Clark, who wrote an enormously influential book on the nude, where he actually gave this particular painting as an example of something that Giovanni Bellini may have known. And he specifically showed the example on the right, the figure of Prudence, from a great cycle of pictures in the Accademia in Venice.

And we wanted to actually sort of test that hypothesis. And in fact, since the Memling was actually made for a Bolognese patron, it could’ve been in Italy when Bellini was working. He might have known it. But as likely, he could also have known another work by Memling, or maybe the works by Rogier. So that in fact, this Bellini, which does have a northern quality, does seem to provide evidence of that flow of ideas from north to south.

CUNO: Now, one of the sources of the nude figure from antiquity, of course, is sculpture. But we have an example of a different kind of sculpture here, which although in its capacity to articulate the human form, might have some origin in antiquity. But describe this for us, because it is an extraordinary aggressive emotional figure of Saint Jerome.

KREN: This is indeed an extraordinary sculpture. A particular section of the exhibition is devoted to images of nude figures that are not beautiful, that have different physical or emotional states that make them less, if you like, less than ideal or less than gorgeous or ravishing. And this was particularly common in Christian subject matter, because much of the Christian narrative talked about saints who were disrobed and tortured. Or in the case of Saint Jerome, this sculpture here, or another image in the show of Saint John the Baptist, some of the saints actually withdrew from worldly existence, to a very simple and basic existence in the desert, and not being concerned about their own physical beauty or wellbeing, and focusing instead on a life of prayer and Bible study and meditation on the meaning of the Christian narrative.

Saint Jerome is one of the greatest figures of that type. And here, he’s shown actually in a full-sized figure, actually fully polychromed. This was a genre of which not many well-preserved examples survive, but was a very important genre of the time that clearly showed how much the nude belonged to a context where realistic imagery, immediate, raw, if you like, very, very present imagery, was incredibly important.

CUNO: And as you mention, it’s fully polychromed. In fact, it’s so fully polychromed it looks as if it was painted yesterday.

KREN: It is actually an example of well-preserved polychromy. It was actually recently conserved. What’s actually really wonderful about it is the wood itself—it’s a wooden sculpture—was carved to actually show the veins, to show, as it were, like, the very worn quality of his body.

I mean, it is [a] very, very highly detailed image. And polychromy doesn’t mask any of that. It makes the physical textures of Jerome’s being very, very apparent.

CUNO: But just opposite the Saint Jerome is this exquisite small, and now artist-unknown, elderly bather, as described. Talk to us about this and what role this sculpture might have played.

KREN: This is actually an equally extraordinary sculpture, from southern Germany, which shows an elderly woman. Her skin is worn, her breasts are sagging. She looks exhausted and almost on the verge of tears. But she has a very distinctive pose, which is the pose of what they call the Venus Putica, the Modest Venus, whose hand reaches down to cover her genitals.

And that reference is unquestionably deliberate. It basically is a reference to the notion of beauty, the ideal of beauty that one associates with youth, and a reminder—and this was a very, very common theme in European art at this time—of the transience of beauty itself. And in fact, if one looks— walks behind the figure—and I encourage the visitor to do so—you actually see that her back side is actually much smoother and more shapely, in the manner of a younger woman.

CUNO: These two sculptures we’ve just been talking about, set within the context of prints and drawings of the human figure, the nude figure, what is a history of figure drawing that might be illustrative of the development of the regard of the human figure in this exhibition?

KREN: What we do know, and what’s actually a crucial development for this entire narrative, is that by the second half of the fifteenth century, drawing from life, drawing from the model—specifically actually the male model—became a standard workshop practice. There’s some evidence that—and there is a good argument that could be made—that drawing from life, or at least some kind of working from the live model, existed before the mid-fifteenth century, but the wealth of surviving evidence belongs to the period after 1450.

CUNO: In that respect, tell us about the Pisanello drawing, this exquisite, almost-like-silverpoint drawing on parchment.

KREN: This drawing is quite extraordinary, both within the exhibition and the context of the notion of life drawing. Because as I said, most of what we know about life drawing, most of the examples belong to the period after 1450. And I should emphasize that it starts in Italy.

But we know that Pisanello, who left us literally hundreds of drawings from him and his workshop, did seem to draw from life, was interested in the nude, drew also after the Antique, well before 1450, and may have been really one of the first artists to undertake that. And this drawing of a female model, clearly the same model shown from four different angles— And she seems to actually have been maybe a figure that he actually saw in the baths, because she seems to have on the far right, have some kind of a bath towel that often was worn on the head. Clearly is maybe actually one of the earliest life drawings that survives.

CUNO: So just how early, then, is this drawing?

KREN: From the mid-1420s or the early 1430s.

CUNO: And one these models have come into the studio for the artist to draw, or would he go to the baths, as you describe?

KREN: Well, that’s a very interesting question, because the practice then was basically drawing from the male nude. And so one has to wonder how he had access to the female nude. I think it doesn’t appear to have been considered appropriate to work— at least in the fifteenth century, drawings of nude females are very, very rare. So what the access was, that’s the question that’s not really answered.

CUNO: Well, the drawing to the left of it, by Raphael, is a very, very accomplished, mature, confident drawing of the female nude. Clearly, the kind of privacy of the female nude drawing was not a problem for Raphael. What was the difference, the change from then to the Raphael drawing?

KREN: In a way, the Raphael drawing really marks the beginning of the tradition of drawing from the female nude model, which belongs really to the first quarter of the sixteenth century.

I mean, this is an extraordinary work, where he seems to have used a single model in three different poses, which were then incorporated for the figures of the Three Graces in the great Villa Farnese ceiling, of the marriage of Cupid and Psyche.

CUNO: And it’s just next to a life drawing by Dürer, of a woman described as a nude figure praying. What would be the purpose, then, of that?

KREN: So Dürer’s actually very interesting because his drawings of female nudes, with the exception of Pisanello, generally predate those of the Italian studies of female nudes. So again, sometimes the Germans were— There were a different set of values that maybe allowed them to work from the female nude earlier.

One theory is that she’s actually a study for a figure under the cross, shown in prayer. And you might ask, well, why a nude figure under the cross? And the answer is that it was the practice to draw from the nude, to draw the nude, in order to understand movement, the positioning of the limbs, the anatomy, so that one actually wanted to dress the figure, if you like, that the pose was as convincing as it could be.

CUNO: In this, the penultimate gallery of the exhibition, we’re looking at artistic theory and practice in different ways, looking at the drawings, as you’ve just described them, and their relationship to paintings, and then to sculpture. In the final exhibition gallery, we’re looking at a much different array of works of art that are focused around the theme, personalizing the nude.

Tell us about this exquisite painting by Jean Fouquet, Virgin and Child— It’s a painting as strange and as beautiful as one can imagine a painting to have been at this time. That is, in the second half of the fifteenth century. Describe the painting for us, and also the role that this painting played in the court life of Jean Fouquet and his masters.

KREN: So this is the painting of a Virgin and Child, with the Virgin enthroned, seated on an elaborate bejeweled and tasseled throne, in heaven, with the Christ Child on her lap. And she’s surrounded by heavenly angels, seraphim and cherubim, in the sort of stunning palette of reds and blue. What is striking about the Virgin is that her pose echoes that of a popular iconography of the time, which is called the Madonna lactans, or the nursing Virgin, where the Virgin’s breast is exposed or partially exposed and the child is nursing from it or about to nurse.

What is curious about this painting—and it’s the only example that I know—is that the Christ Child is seated on her knee, but he looks away, across the picture and outside the picture, and basically ignores her and the breast. It’s a sort of non-nursing Virgin. And in fact, what’s he’s looking across is— The painting belongs to a diptych, and the facing panel, which would’ve been on the left, is a portrait of the donor H.N. Chivalier[sp?], who was a high official at the court of King Charles VII.

So how do you explain this sort of strange iconography?

Another feature that I should mention is that her breast, her exposed breast, is perfectly round. The artist has developed a kind of geometry in the representation of all the figures, which gives the subject a very, very powerful sort of purity of form. Frankly, it is a painting with a great erotic power.

And why would this be? It’s a very strange thing. And many people have puzzled over it. There’s a legend that goes back to the sixteenth century, which is almost certainly correct, which was that the sitter is Agnes Sorel, who was the famous mistress of King Charles VII. She was his mistress for about six years, before she died. They had three children together. She was pregnant with the king’s fourth child when she died.

And she was above all, famous for her beauty. And famous also for the way in which the king was completely besotted with her and kept her at his side. She was always a controversial figure at the court. This painting seems to have been painted just a year or two after she died, and probably was conceived as a memorial to her. And a stunning one it is.

CUNO: Well, the Fouquet is next to the Giorgione, Laura. What about this painting, and what is the context for this?

KREN: Giorgione’s painting of a woman who seems to be Laura, identified by the laurel leaves that create a kind of crown behind her, belongs to the earliest years of a genre, a new genre, associated with the Italian Renaissance specifically, called the Belladonna, which is about beautiful women. Sometimes it’s about a specific beautiful woman. And in this particular case, we don’t know who the sitter is, but her features are so specific and seem to be so carefully observed that it probably is also a portrait of an identifiable woman.

The question is—and again, there’s much speculation—is this the mistress of the artist? Is this the Laura of Petrarch? The poet Petrarch, in the fourteenth century, famously wrote poems about his beloved Laura, praising her beauty and her estimable qualities. Is this a painted version of that or is just more broadly, a painted a version of that kind of literary genre that extolled beautiful women and tried to capture their qualities, either in word or here, in paint?

CUNO: Now, I mentioned that this is in the section called Personalizing the Nude? Why that title for this last gallery in the exhibition?

KREN: So I think one of the most important developments in the fifteenth and early sixteenth century, is that fairly quickly, individuals started seeing imagery involving the nude as useful to their personal identity, or self-fashioning, if you like.

And so that for example, a genre of portraiture grew up that, starting, let’s say, with the medals by Pisanello in the middle of the room, where a great figure would commission his portrait as a medal. But on the reverse, he would show an allegorical scene with nude figures, which would be a commentary, for example, on his personal qualities. And these kinds of medals were given away as personal presents.

CUNO: Well, it’s a, you know, triumphant ending to an extraordinary exhibition. And we talked earlier about how difficult it is to get the loans that you want for an exhibition, and you end the exhibition with a reproduction, a virtually life-size reproduction from the Sistine Chapel, by Michelangelo. Describe this, and why this at the end of the exhibition?

KREN: One of the things we were fascinated by as we worked on this show and started pulling together images was that there was irregular but not uncommon stream of opposition to the nude itself, especially for its sensuality, for its seductive qualities.

And those kinds of responses and the conflict and controversies that arose, often in more localized ways—not just in Italy, but across Europe—kind of crystalized over The Last Judgment fresco of Michelangelo in the Sistine ceiling. This great work was created in the 1530s, essentially, after the period of the show, so it’s a kind of coda to the show. But not only does it embody the triumph of the nude in European art because The Last Judgment was a work that was widely, widely copied and imitated by artists everywhere; but also because it sort of occasioned a firestorm of criticism and reaction, because of the complete nudity of many of the figures. In fact, at one point in the— I think it was the 1560s—the genitals of a number of the figures were painted over with sort of masking sort of loincloths. So it just seemed like the right work in which to sort of summarize what the previous 130 years had sort of paved the way for.

CUNO: Well, Tom, it’s a major triumph, and thank you so much for giving us not only the exhibition, but time on this podcast to talk with you about the exhibition.

KREN: Well thank you very much Jim. It really has been a great pleasure to talk about it.

CUNO: Our theme music comes from “The Dharma at Big Sur,” composed by John Adams for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. It is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts or Google Play Music. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts. Thanks for listening.

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

THOMAS KREN: The nude actually made people uncomfortable in the Renaissance. It certainly provoked...

Music Credits

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.