The West Pavilion of the Getty Center contains a surprise, the cabinet-like space known as Gallery W104. For the past three years, W104 has hosted a changing display of drawings and watercolors related to exhibitions nearby—most often, the one just across the hall. The displays feature recent acquisitions, sometimes made possible through generous gifts, and, as is the case this summer, special loans from collectors.

The current display in W104 relates to the large loan exhibition Gustav Klimt: The Magic of Line in the Exhibitions Pavilion, but also to Messerschimdt and Modernity in the adjacent galleries. It features four very fine works made around 1900, including three colorful drawings by Fernand Khnopff, Alphonse Mucha, and František Kupka, and an oil sketch by Franz Matsch. All four artists were contemporaries of Klimt in the artistic world of fin-de-siècle Vienna and Prague, all were trained in conventional art academies, and all broke in varying degrees toward the avant-garde.

Study for the poster Fruit, 1897, Alphonse Mucha. Pastel, 25 9/16 x 15 3/8 in. Lent by Eva and Brian Sweeney

This pastel study by Mucha for his Art Nouveau poster Fruit was created in 1897, the same year Klimt broke away from the art establishment to form the Secession. The powerful V shape of the woman’s elbow juts out from the halo-like circle around her head, creating a tension between action and repose.

Also executed in pastel, but as electrifying as the Mucha is soothing, is Kupka’s 1908 study Girl Shading Her Eyes, which joined the Museum’s collection in 2010. Intense purples and greens shadow a girl’s face and offer a stark contrast to her spotlit torso, with its small nipples and quickly sketched ribs. Like the Mucha, this, too, was a study for another work, his painting Girl with a Ball.

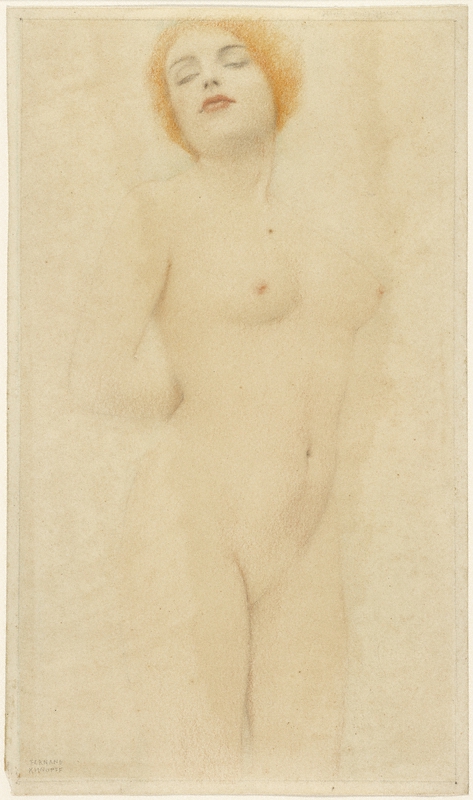

Study of a Nude, about 1912, Fernand Khnopff. Colored crayon on cream wove paper, 12 13/16 x 7 5/16 in. Lent by Eva and Brian Sweeney

Rounding out the trio of sketches is Khnopff’s crayon Study of a Nude, a work as fleshy and voluptuous as his painting in a nearby gallery, the portrait of Jeanne Kéfer, is dreamlike and innocent. Khnopff’s enchanted eroticism directly influenced Klimt; as in Klimt’s sketches of women, the model seems close enough to touch, but we are not invited into her private emotional world.

Oil sketch for The Triumph of Light over Darkness, 1897, Franz Matsch. Oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 38 1/4 in. Private Collection, Los Angeles

The fourth work in the gallery, this oil sketch by Matsch offers an illuminating contrast to Klimt’s work. In 1894, the two young Viennese artists were commissioned by Vienna’s university to create ceiling paintings representing knowledge and human advancement. Made in preparation for this project, Matsch’s luminous oil sketch for The Triumph of Light over Darkness presents a radiant personification of Enlightenment surrounded by angelic attendants—a radical contrast to Klimt’s anxious and complex visions. Klimt’s so-called faculty paintings were considered too avant-garde and were rejected; they were destroyed by fire at the end of World War II. The preparatory sketches in Gustav Klimt: The Magic of Line are the closest we can now come to the lost paintings.

The four works in W104 are on view through September 23, which also marks the close of Gustav Klimt: The Magic of Line. Find this gallery on the plaza level of the West Pavilion, on the left side of the walkway leading to European decorative arts and sculpture from the two centuries leading up to 1900.

Comments on this post are now closed.