For the third year in a row, award-winning children’s fantasy author Cornelia Funke joined us at the Getty Center for a storytelling event continuing the adventure of the ghost of real-life pirate William Dampier. This time, Dampier’s mission to keep the other spirits haunting the Getty Center at bay took him on a voyage deep into the cave temples of Dunhuang, China, the focus of a new Getty exhibition. You can hear audio of Cornelia’s storytelling event below.

Before the event, I met Cornelia at her studio for a conversation about her inspirations and creative process.

Rebecca Peabody: Cornelia, this is the third year in row that you’ve written a story set at the Getty Center—can you tell us how your collaboration with the Getty came about?

Cornelia Funke: I had done so much research for my series MirrorWorld at the Getty Research Institute (GRI), and it was so inspiring for me and so enriching for my process that I wanted to find a way to give something back. I thought that one way to return the favor would be to write about a GRI exhibition in a way that would show a certain perspective, a younger perspective, toward the material and make it accessible to younger children.

I knew we would need a memorable character to lead children through a story like this. I didn’t want to just make someone up, since the GRI is so much about the magic of reality—I wanted to use a historical character. In my research at the GRI, I came across William Dampier, a British explorer who lived in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. He was a very successful pirate, but also a cartographer and writer who became famous for his books.

It was such a perfect find that I was almost like, “Is this real?” But, yes, he’s on some stamps in South America and there are many images of him, which was also wonderful. So, I had a portrait. I had paintings. I could imagine him. I thought, perhaps Dampier’s ghost came to the GRI in a compass, because some of his cartography is in the GRI’s collections. Perhaps he’s here to serve as a guardian in order to make up for all the plundering he did. Now he is guarding treasure—the GRI’s treasure—which makes perfect sense, right? And after walking around the Getty, I found a few other objects in different buildings that I could imagine bringing ghosts with them, which meant that those buildings, too, might have guardians that could help Dampier with his mission.

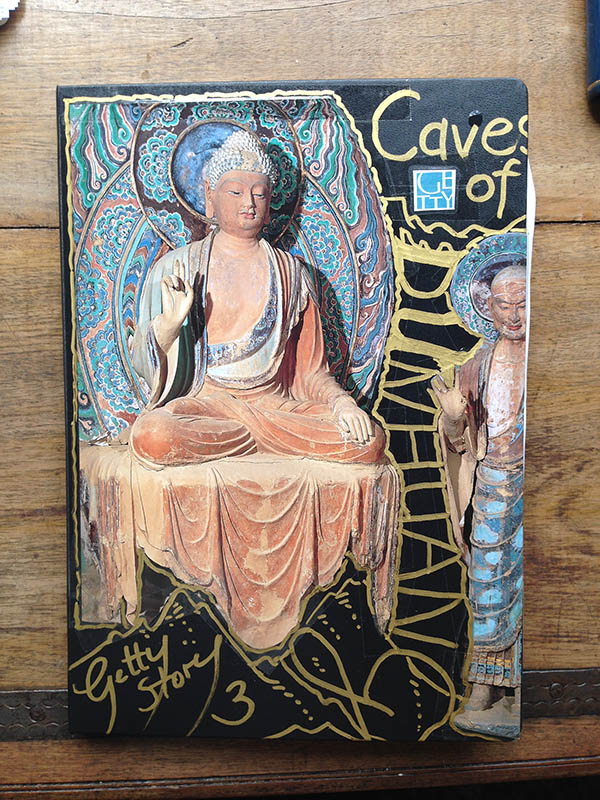

Cornelia Funke’s research notebook for “Voyage into the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas.” Photo: Rebecca Peabody. All rights reserved

The story about the Dunhuang caves is interesting because so much comes from beyond the Getty: the artists, the caves, the artifacts—maybe even the ghosts. I saw all of the artifacts in a PowerPoint presentation before the exhibition opened, but decided that I should really hold back on writing the story until I’d seen the actual exhibit. More than my first two stories, this one will be very much about the experience of being in the exhibition, in the installation.

Can you tell us about your creative process as a writer? You’ve shared a beautiful notebook with me. Are these notebooks how you pull together all of the research that you do around a story?

Inside one of Cornelia Funke’s research notebooks

Yes, I thought this notebook would be a good example because it’s for a short story so it is similar to the books I have done in the past for my other Getty stories, and to the one I will do for the Dunhuang caves story.

This is for a story I did for my Swedish publishers—a fairy tale set in Stockholm in 1860. If you look through it, you’ll see that there’s historical research, research on fairy tales and myths, and then you will see my first handwritten draft, and the first printed draft, and then the illustrations. The notebook lets me pull everything I have together in one place. I draw a lot as I’m getting into my stories, especially when they’re about visual material.

Do you complete a notebook like this before you start writing, or do you compose it as you’re in the process?

The notebook continues to grow as I create the story. I will include a finished draft of the story in the notebook at the end of the process, and if the story involved illustrations, copies of those as well. The notebooks are a way for me to say, “Okay, this captures all the work I did on this story.” A shorter story might only have one notebook. But a novel might have many more; when I write by hand, I can easily fill 30 notebooks.

Do you compose your novels by hand?

Yes, I write the first draft by hand. I think being able to see the process of the artist can be such a magical thing. I always take these notebooks to readings. There is no greater enchantment on the faces of your readers than when they are allowed to look through your book, and they can go into your mind and trace your thoughts.

I’m very grateful that working with the Getty gave me the opportunity to stand among such important artifacts and documents, and to realize: “Yes, this is how human history and human thought should be written down so that we can always feel it.” If you look at the sketchbook of an artist from the 16th century it will tell you so much more about him than just a painting that’s fully executed. Even if you read a thousand essays on the painting, they still won’t give you the same insight that you have when you look at the sketchbooks. There’s this wonderful Robert Louis Stevenson quote: “Don’t judge each day by the harvest you reap but by the seeds that you plant.” I think that idea is so beautiful, and also a perfect summary of something important that we all need to remember: documenting the creative process is just as important as its end result.

Children’s author Cornelia Funke at work in her studio, “The Writing House.” Photo: Rebecca Peabody. All rights reserved

______

Cornelia Funke’s Voyage into the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas took place June 19, 2016, at 11:00 a.m. The exhibition Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road is on view at the Getty Center through September 4, 2016.

Comments on this post are now closed.