Long Live the Motherland, Beijing No. 5, 2011. Copyright Chen Man. Courtesy of L.A. Louver

Chinese photographer Chen Man has been witness to the dizzying modernization of China of the last 20 years. She recalls growing up in the quiet hutongs (alleyways) of Beijing, at a time when people were mostly riding bicycles to get around. Now most of those hutongs have made way to high-rise apartments, as Beijing becomes one of the most crowded cities in the world – and one of the most polluted due to the vast number of private cars.

These days Chen has been spending more time in California, partly because she’s married to a Chinese American and they have a young child. She’s also enjoying a large solo show, “Chen Man East-West,” which occupies both floors of L.A. Louver, a gallery based in Venice, California. Having heard of her reputation beforehand — she’s famous in China, hardly known here in the U. S. — I went for a preview of the exhibition one afternoon and had a chance to talk with her.

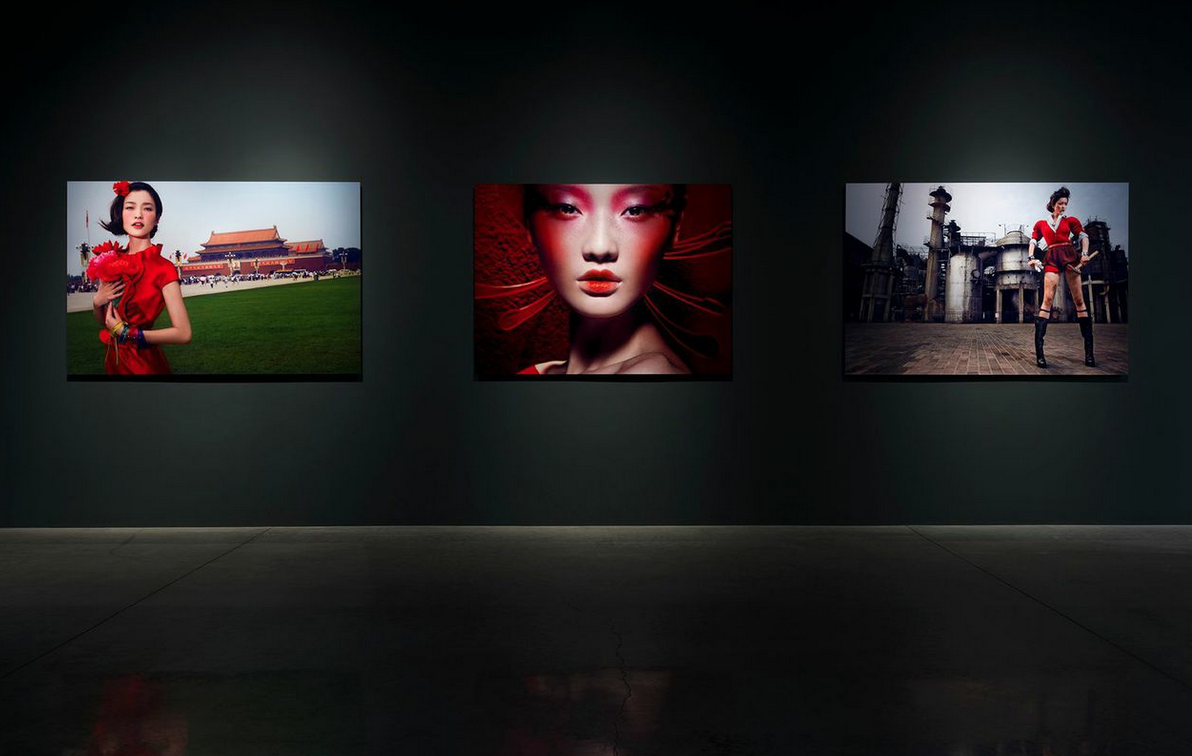

Installation view of “Chen Man: East-West” at L.A. Louver, 2014. Courtesy of L.A. Louver

Now in her mid-30s, Chen grew up in the post-Mao era—a fast-paced world defined by hectic commercialism and an influx of Western visitors, goods, and culture. In one of her talks, she has referred to the West obliquely by saying, “We love to drive your cars, drink your coffee, and carry your handbags.” There’s a rueful irony in her voice as she says this. She’s been exposed to American and European movies, magazines, and advertising, and one can see those influences in the provocative photography in L.A. Louver’s main gallery downstairs. Meanwhile, her more sedate brush paintings and calligraphies are upstairs.

Chen began drawing and painting as a small child, and later attended the Central Academy of Fine Arts, one of the most important Chinese art schools. She took up photography while there, and worked her way into shooting for Vision Magazine, which sounds to me like a combination of Vogue with hipper street elements. “I learned to do everything for my work – lighting, make-up, styling,” she says during our conversation. “In those days there weren’t those specific jobs. Well, not much even today.” These skills have served her well in creating her striking images, which combine studio photography and digital manipulation.

Young Pioneer with the Three Gorges, 2008

Copyright Chen Man. Courtesy of L.A. Louver

The large photographs in the exhibition are her personal creations. She loves to juxtapose the old and the new, the traditional and the avant-garde. Some look like shots from a slick magazine – a fashion model dressed in bright red, holding a bright red flower, with the Heavenly Gate of the Forbidden City behind her, or another model in a bright red dress and red high heeled shoes, posing with young men in striped T-shirts and bicycles in what looks like one of the few remaining hutongs in Old Beijing.

Cotton 6, 2008

Copyright Chen Man. Courtesy of L.A. Louver

Five Elements: Earth, 2011

Copyright Chen Man. Courtesy of L.A. Louver

In two of her series, she refers to ancient Chinese philosophy using semi-nude female models to add an over-the-top level of fantasy. The images in “Five Elements,” she says, are about cycles, and how one element evolves into the next, and how the old and the new exist side by side in today’s China. For each “element” (also sometimes defined as “phase” or “process”), she juxtaposes two photographs – a large one on the wall that features a powerful goddess and a smaller one on the floor that shows a middle-age woman, in a real-life setting. One of my favorites is “Earth,” showing a demon woman rising from a fissure in the road, naked like a dark Venus – she has caused an earthquake, and buildings behind her are burning and collapsing. Meanwhile she looks out coolly, her hair flying and her hands strategically covering her crotch. The counterpart photograph is of a stout, smiling woman in some kind of factory – she’s the salt of the earth, a working stiff.

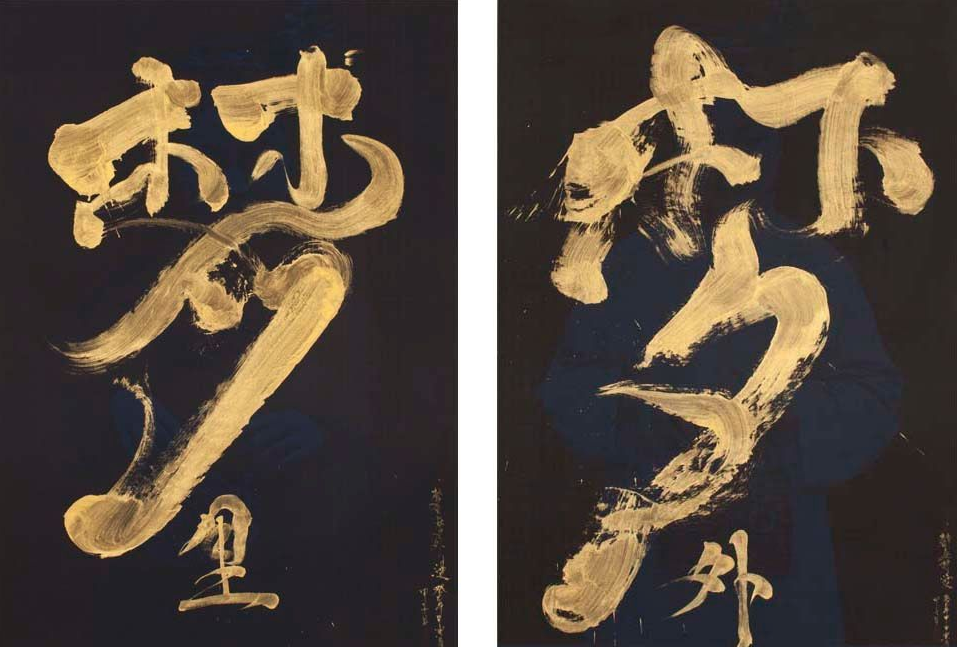

Outside Inside the Dream, 2012

Copyright Chen Man. Courtesy of L.A. Louver

Upstairs at Louver is the other side of Chen Man – the side that studied traditional Chinese brush painting and calligraphy. Her brushwork is highly skilled, both controlled and expressive. About a dozen works on paper are here, portraits of monk-life figures and Chinese characters. One couplet of calligraphy hangs on the wall, in two frames. Both feature the word “meng” (or dream) in Chinese, with a smaller character below saying “inner” in one and “outer” in the other. Here we see the Buddhist influence in her work, and her understanding that the material world is illusion. And at the same time, she is a realist: “All reality is a phantom, all phantoms are real,” she has said.

Text of this post © Zócalo Public Square. All rights reserved.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.