Buried during the catastrophe that felled a city, a recently rediscovered collection of ivory plaques provides a glimpse into the early Byzantine world

Plaque with the Life of Achilles (one of three), about A.D. 300–350, made in Constantinople or Thessaloniki; found in Eleutherna, Crete, Greece. Ivory, 3 3/4 x 15 9/16 in. Image courtesy of the Rethymno Archaeological Museum

Imagine if a powerful and destructive earthquake struck Los Angeles. What would you do if you knew those were your final moments? What would be left after you were gone?

On July 21 in the year 365, a powerful earthquake leveled Eleutherna, an important city southeast of modern Rethymnon on Crete. Over 1500 years later, from 1985 to 2003, a team of Greek archaeologists under the direction of Professor Petros Themelis brought to light a number of buildings in the southwest part of the city, including House I, a lavish urban villa. Hidden within the debris in Rooms 100 and 116 (see the plan below) were more than 145 fragments of ivory, among them three ivory plaques currently displayed in Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections at the Getty Villa.

On July 21 in the year 365, a powerful earthquake leveled Eleutherna, an important city southeast of modern Rethymnon on Crete. Over 1500 years later, from 1985 to 2003, a team of Greek archaeologists under the direction of Professor Petros Themelis brought to light a number of buildings in the southwest part of the city, including House I, a lavish urban villa. Hidden within the debris in Rooms 100 and 116 (see the plan below) were more than 145 fragments of ivory, among them three ivory plaques currently displayed in Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections at the Getty Villa.

These plaques were once affixed to the sides of two cherished wooden coffers. The selection of imagery and quality of carving on these boxes provide precious information about the wealth and erudition of a fourth-century couple whose lives were interrupted by natural disaster.

Floor plan of House I in Eleutherna, Greece, where the carved ivories were excavated. Image from Petros G. Themelis, Ancient Eleutherna: Sector 1, Volume 1. Athens: University of Crete, 2009, p. 64, fig. 24

The large urban villa where these ivories were found once accommodated an extended family. It was richly decorated with marble and limestone columns and had painted walls. Room 100 was a large banquet hall that could have accommodated many people. The house also included a work area (Rooms 6 and 7), a cellar (Room 8), and a room furnished with chests and closets for the family (Room 9).

In the peristyle (courtyard) immediately outside of rooms 100 and 116 were found the skeletons of a couple that died as they protectively embraced their young child, likely the child for whom the coffer was first offered as a gift.

Skeletal remains of a family found during excavations at House I in Eleutherna. An earthquake destroyed the city in A.D. 365. Image from Petros G. Themelis, Ancient Eleutherna: Sector 1, Volume 1. Athens: University of Crete, 2009, p. 70, fig. 36

More about this family’s story can be learned through large number of personal objects also found in the demolished house, which included ceramic vessels, glass beads, coins, gold rings, bronze objects, carved bones, and ivory.

A Newborn’s Coffer

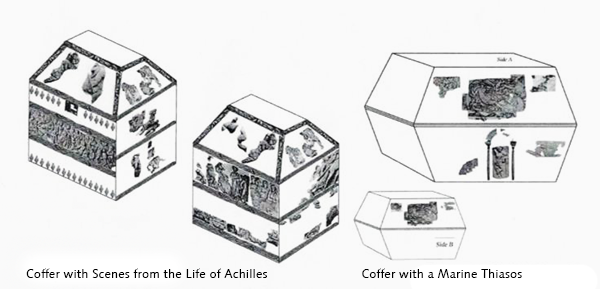

Diagram showing how the Byzantine ivories found in House I were once applied to their wooden coffers. Illustration from Magda Vasiliadou, “The Ivory Plaques of Eleutherna and Their Workshop” (Paper presented at the second Hellenistic Studies Workshop, Alexandria, Egypt, July 4–11, 2010)

Ivory fragments were discovered in rooms 100 and 116 of House I in Eleutherna. The coffers to which they were once affixed have been reconstructed as shown in the illustration above, with truncated pyramidal lids and rectangular and truncated bases. The ivories are carved with subjects derived from Greek mythology: the story of Achilles, the Greek hero and main character of Homer’s Iliad, and a Marine Thiasos (the triumphal wedding procession of Poseidon and Amphitrite).

The fragments exhibited now at the Getty Villa in Heaven and Earth include four scenes from the life of Achilles: his birth, his submersion in the river Styx, his placement in the care of the centaur Chiron, and his dragging the body of Hector, leader of the Trojans, behind his chariot during Patroclus’s funeral games.

Monuments in miniature (here and above): Plaques with the Life of Achilles, about A.D. 300–350, made in Constantinople or Thessaloniki; found in Eleutherna, Crete, Greece. Ivory, 4 1/8 x 4 7/8 in. (plaque above); 3 13/16 x 6 1/4 in. Images courtesy of the Rethymno Archaeological Museum

The second coffer, not included in the exhibition, was decorated with a Marine Thiasos, attended by such figures as sea nymphs and hippocamps. Based on their subject matter, the coffers are thought to have been gifts to a couple to commemorate their marriage (the Marine Thiasos coffer) and to celebrate the birth of their son (the Achilles coffer).

The Eleutherna ivories during their excavation in Greece. Image from Petros G. Themelis, Ancient Eleutherna: Sector 1, Volume 1. Athens: University of Crete, 2009, p. 67, fig. 30

Though small in size, the ivories are carved in a monumental style reminiscent of large-scale sculpture of the same period. Just down the hall from the exhibited ivories at the Getty Villa, for example, a much larger sarcophagus panel made around the year 210 and decorated with the story Endymion and Selene contains many of the elements represented on the coffers; it also offers clues about the kinds of sculptural sources that would have been available to the carver of the Eleutherna ivories.

Sarcophagus Panel with the Myth of Endymion and Selene, about A.D. 210, Roman. Marble, 21 3/8 x 84 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 76.AA.8

The imagery on the coffer also foreshadows compositions that would later appear in Christian art. The representation of the hero’s birth—in which a midwife prepares to bathe the child in a basin as his mother, the Nereid Thetis, reclines on a couch and is attended by female servants—recalls representations of the Nativity of Christ and the Birth of the Virgin, including a gilded icon found in the exhibition Heaven and Earth.

Why These Images?

At the time in which these ivories were carved, the late 3rd and early 4th centuries AD, Christianity had already begun to spread throughout the Roman Empire. At the same time, however, heroic scenes from ancient mythology continued to excite the imagination of many, particularly as sources of secular art.

Veroli Casket, A.D. 950–1000, made in Constantinople. Wood overlaid with carved ivory and bone plaques with traces of polychrome and gilding, 40.3 x 15.5̫16 x 11.5 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, 216-1865. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Interestingly, mythological scenes continued to be used in medieval Byzantium for the decoration of ivory boxes, most notably the Veroli Casket from the second half of the tenth century, today in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Another example can be seen on a twelfth-century bone casket box, also displayed in Heaven and Earth, which depicts putti dancing with real and fictitious creatures. The continuous use of mythological scenes for the decoration of luxury objects is often seen as an indication of elite tastes and levels of education.

The couple discovered in House I lived at a time of radical transformation. After the earthquake, the rebuilt, early-fifth-century city of Eleutherna contained an episcopal church and additional basilicas. These architectural remains witness the rapid spread of Christianity. Fragments of the older, earthquake-damaged buildings were used as fill for the new structures, and carvings and inscriptions—including spolia (reused sculptural elements) from pagan buildings were employed as construction material for the new basilicas.

Personal items such as these ivory plaques open a window into the lives of the people who lived in a world of rapidly transforming art, religion, and society. An examination of the two coffers teaches us what one couple from Cretan Eleutherna celebrated and what was important to them. Studying these fragments reminds us that archaeologists are not just unearthing artifacts, but that they are also uncovering the stories of the people who made and used them.

_______

For addition reading, see Magdalini Vasiliadou, “The Ivory Plaques of Eleutherna and their Workshop,” in Second Hellenistic Studies Workshop, ed. Kyriakos Savvopoulos (Alexandria, 2011).

Text of this post © Christina Lincir. All rights reserved.

The excavator of Eleftherna, Crete is professor Nikolaos Stambolidis. Petros Themelis is excavating in ancient Messene. Please correct.