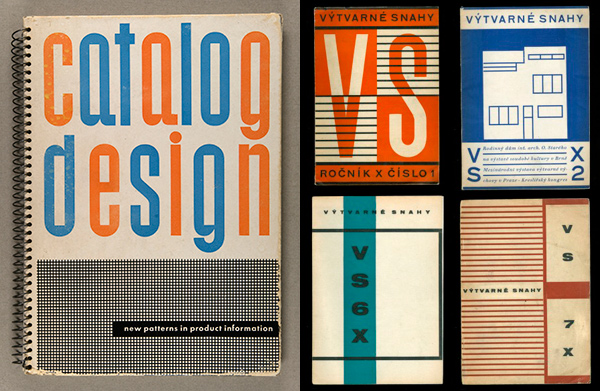

Designs by Sutnar: Catalog in the collection of the Rochester Institute of Technology (left); Covers designed by Sutnar for the periodical Výtvarné snahy, 1928–29. Smithsonian Libraries. Purchased by the Margery F. Masinter Endowment for the National Design Library

I’ve just returned from the Czech Republic, where I proudly accepted the 2014 Ladislav Sutnar Prize on behalf of the Getty. Launched in 2012, this prize is awarded annually by the Ladislav Sutnar Faculty of Design and Art at the University of West Bohemia in the Czech Republic for distinction in the fine arts, especially applied arts and design. The other recipients this year were American designer and author Steven Heller, Czech designers Jiří Šetlík and Zdeněk Ziegler, and the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague.

Though far from a household name, Ladislav Sutnar is a giant in the history of design. A Czech American who had a prolific career in his native Czechoslovakia in the 1920s and ‘30s and subsequently in the United States, he was an innovator in graphics, product design, exhibition design, and information design—a forerunner of web design. He is particularly known for his work in typography, including the innovation of adding parentheses around area codes in phone numbers, a seemingly small change that makes long strings of digits easier to read and remember.

Sutnar is no stranger to us at the Getty. The Research Institute has five separate collections related to his work, including decades of his papers. All areas of Sutnar’s design projects are represented in these archival holdings, with highlights including prototypes for the “Build the Town” children’s block set and documentation of the Czechoslovakian Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

The Czechoslovakian Pavilion played a pivotal role in Sutnar’s life. While he was visiting New York for its opening in 1939, Germany invaded Czechoslovkia, and Sutnar was asked by the occupying government to stop construction. He refused, instead working with the Czech government-in-exile to open it as planned. Sutnar remained in the United States to avoid retribution from the Nazis and was later joined here by his family; he became a U.S. citizen in 1948.

A significant portion of the Research Institute’s collection relates to Sutnar’s career from the ‘60s, when he returned to painting and drawing with a focus on female nudes. In addition to prints from his portfolio Strip Street, the archive incluces studies and small paintings from the geometrically constructed nudes in his Venus series.

Touring the Ladislav Sutnar Faculty of Design and Art with its dean (center). I am at far right with Steven Heller.

It is due to Sutnar’s son, Los Angeles architect Radislav Sutnar, that these archives are part of the Getty’s collections. Speaking about his father in a 2011 Atlantic article, Rad remembered him “as a visionary who expressed his thoughts through design and painting…one of a kind and ageless.” Rad also ensured that other important collections of Sutnar’s work are preserved at other U.S. institutions, including the Rochester Institute of Technology, Yale, and Cooper-Hewitt—which last year received a Sutner Prize as well.

The Sutnar Prize ceremony took place in the Pilsen City Hall with great fanfare, and included the presentation of a work of art by Ladislav Sutnar to the mayor. The following day, the Faculty of Design and Art hosted an all-day symposium on Sutnar. The activities ended on a solemn note as the ashes of Sutnar and his wife, Františka, were returned their native Pilsen, interred together in a grave with a monument designed to memorialize Sutnar’s incredible life and work.

We’re honored to have been included in this occasion and, through our collections, to play a role in keeping Ladislav Sutnar’s design legacy alive.

Symposium on Ladislav Sutner at the Faculty of Design and Art in Pilsen

American and Czech flags with the ashes of Ladislav Sutnar, which were returned to the Czech Republic.

Comments on this post are now closed.