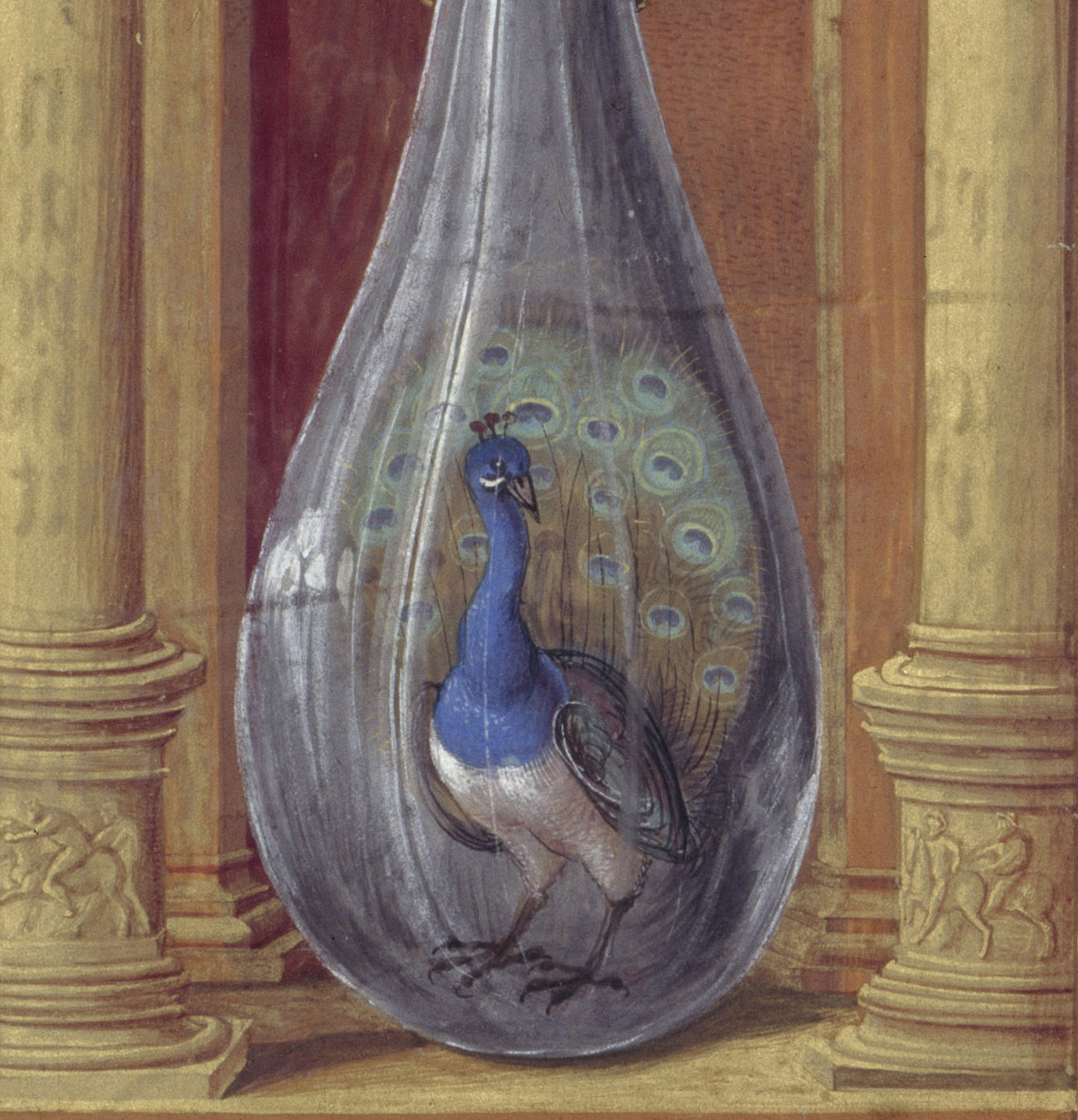

The Peacock Stage (detail), attributed to Jörg Breu the Elder, (German, ca. 1475–1537). Miniature from the illuminated manuscript Splendor solis oder Sonnenglanz, fol. 28r, 1531–32. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, Cod. 78 D 3

In alchemical writings, certain symbols, including humans, birds, and animals, stand in for particular stages of the alchemy process. The peacock, with its colorful feathers, serves as a metaphor for the phase when the greasy black contents of the alembic suddenly turn iridescent in the flask, producing a rainbow of colors like the shimmering reflection of light in an oil slick. It is known as the peacock stage, or the chemical rainbow. Where does this exceptional image come from?

It is part of the illuminated manuscript Splendor solis oder Sonnenglanz (Splendor of the Sun), one of the main works of the alchemical tradition. The original book, dated 1531 to 1532, now resides in the Berlin Kupferstichkabinett, and it formed the basis of many editions from the early sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries.

The miniatures in Splendor solis are doubtless among the most beautiful and best-known alchemical images. There are few publications on alchemy that do not depict an image from the book. William Butler Yeats praised the manuscript in his short story “Rosa Alchemica” (1913), and for James Joyce it was the inspiration for a chapter in Finnegans Wake (1939). The famous alchemist and European inventor of porcelain, Johann Friedrich Böttcher, is said to have turned to Splendor solis in pursuit of the production of gold.

The manuscript draws on earlier sources to illuminate the mysterious process of alchemy—including the peacock stage—in innovative ways. But who created this sumptuous, influential work of art?

A Legendary Author?

Salomon Trismosin, who was supposedly the teacher of the famous Paracelsus, is often mentioned as the author of Splendor solis. This attribution is particularly widespread in the English-speaking world, as the hermetic Julius Kohn published an English translation of the German text of Splendor solis in 1920 and identified Trismosin as the original author. Trismosin’s reputation as a legendary figure with supernatural powers—he is said to have lived to over 150 or even 200 years—did little to rebut this attribution.

The German text of Splendor solis is based on older alchemical writings, most of which are from the fifteenth century. Even though it is possible that there is an earlier, lost version of Splendor solis from the tail end of that century, the nature of the book indicates that it was not produced before the 1520s, as Splendor solis is based to a considerable degree on the alchemical illuminated manuscript Aurora consurgens. The original Aurora consurgens dates to around 1410, but rather than reverting to one of the Latin versions from the fifteenth century, the author of Splendor solis absorbed the richly illustrated German translation of about 1520.

The writer of Splendor solis took Aurora consurgens and turned it into a new text in a kind of patchwork process. The close relationship between the books is evident in the whole sentences and passages that the author reused.

The provenance of Splendor solis is nearly as enigmatic as its authorship. Even though the original Berlin manuscript of 1531 to 1532 is elaborate, opulent, and was expensive to produce, there is no hint as to its patron.

Breu’s Method

With the miniatures, the painter used a similar method as the author and drew inspiration from earlier sources. We are also still not entirely certain about the identity of the artist. In my 2004 monograph on Splendor solis, I attributed the miniatures to the painter Jörg Breu the Elder from Augsburg, Germany. Stylistic similarities link the book’s images to the work of this painter and contradict possible attributions to Nuremberg painters such as Nikolaus Glockendon and Sebald Beham.

In his series of ink drawings of the seven planets and their children from 1510 to 1515, Breu drew on different models of the motif, such as the Florentine series of engravings from the circle of Baccio Baldini and interpretations created north of the alps. He combined these sources to produce new depictions of the children of the planets, in a process that was particular to him. The miniatures of Splendor solis feature the same method of compilation as the ink drawings.

The use of many different images as models in the 22 miniatures of Splendor solis is particularly noticeable in the seven paintings of the children of the planets. The art-historical literature mostly ascribes the imagery to the woodcuts of Georg Pencz. Pencz’s woodcuts date to 1531, which has therefore been considered the earliest possible date for Splendor solis. But the manuscript’s artist also absorbed numerous other sources.

Left: Sol and His Children, attributed to Jörg Breu the Elder, (German, ca. 1475–1537). Miniature from the illuminated manuscript Splendor solis oder Sonnenglanz, fol. 24r, 1531–32. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, Cod. 78 D 3. Right: Philosopher Tree, attributed to Jörg Breu the Elder, (German, ca. 1475–1537). Miniature from the illuminated manuscript Splendor solis oder Sonnenglanz, fol. 13r, 1531–32. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, Cod. 78 D 3. Images © Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz. Photos: Jörg P. Anders. Images licensed under a href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/de/deed.en”>Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Germany License

Underpinning the writings and images of Splendor solis is the medieval concept of a florilegium, a collection of extracts from other texts. It is particularly noticeable in the miniatures, which are based on images from many of the best-known alchemical manuscripts. Copies of illuminated tracts such as Donum Dei, Rosarium philosophorum, and the Book of the Holy Trinity were already in circulation at the time when Splendor solis was made, and Breu used them for the creation of his miniatures.

Although Splendor solis shows a strong dependency on Aurora consurgens, the author never mentions it as a source. But the book’s title, Splendor solis or Splendor of the Sun, could contain an implicit hint at the connection—and the later manuscript’s surpassing opulence. Aurora consurgens, which translates from Latin as the rising dawn, is followed by splendor solis, the shining sun. With the title, the mastermind of this work expressed how the book was consciously conceived as the most splendid work of all alchemical manuscripts.

The miniatures, which were inspired by illustrations from earlier alchemical manuscripts, shine brighter than their predecessors and eclipse their beauty and grandeur. The sun stands at the zenith of the sky, and the Splendor solis can rightly be called the climax of alchemical imagery.

Merging Alchemy with Astrology

Featured in seven of the miniatures in Splendor solis, the planet-children constitute an important iconographical element of the manuscript. The series features the seven planets of the Ptolemaic system—Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Sun, Venus, Mercury, and Moon—which were revered as deities. In each of the miniatures, one of the seven planetary gods presides over a group of people on earth below whose lifes are shaped by the characteristics of the god in question. They are designated as that deity’s children

Left: Jupiter and His Children, attributed to Jörg Breu the Elder, (German, ca. 1475–1537). Miniature from the illuminated manuscript Splendor solis oder Sonnenglanz, fol. 22r, 1531–32. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, Cod. 78 D 3. Right: Mars and His Children, attributed to Jörg Breu the Elder, (German, ca. 1475–1537). Miniature from the illuminated manuscript Splendor solis oder Sonnenglanz, fol. 23r, 1531–32. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, Cod. 78 D 3. Images © Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz. Photos: Jörg P. Anders. Images licensed under a href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/de/deed.en”>Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Germany License

The planetary series in Splendor solis deviates from all its counterparts in one significant regard: there is a panel at the center of each miniature featuring a glass vessel. This picture within a picture showcases a particular alchemical stage. Over the course of the series, the process of transmutation is illustrated in seven phases, with each one symbolized by the contents of the glass container.

The combination of the planet-children iconography with this series of alchemical vessels appears to have been an original idea on the part of Breu, for there are no other existing examples. It is also the only concrete instance of the blending of alchemical and astrological iconography.

The dimensions of the glass flasks and the tabernacle-like character of the niches create a quasi-sacred atmosphere, the majesty of which is heightened by the inclusion of a crown and, in some cases, an additional laurel wreath. The motif of the glass vessel filled with various symbolic contents is featured in allegorical alchemical miniatures dating as far back as the late fourteenth century; it may have been inspired by technical drawings in earlier alchemical manuscripts.

These containers also exhibit a remarkable likeness to medieval depictions of the fetus inside the womb, for they bear a striking resemblance to the motif of the homunculus, a human being generated artificially within the alchemist’s alembic. Such illustrations might be regarded as the forerunners of the painted glass flasks in numerous fifteenth-century illuminated manuscripts.

The only pre-existing sequence of pictures illustrating the various stages of the alchemical process in this manner can be found in editions of Donum Dei, originally created in the second half of the fifteenth century, which likely served as the main model for this section of Splendor solis. Whereas Donum Dei features twelve uncrowned flasks, Splendor solis includes seven crowned glass vessels, which invoke the seven planets and the metals attributed to them. In three instances, the painter copied the contents of flasks from Donum Dei: the dragon, the white queen, and the red king.

The Peacock Stage

Both Splendor solis and Donum Dei include images of the so-called peacock stage, the colorful apparition part of the transmutation process. In contrast to Donum Dei, which depicts the chemical reaction as a series of brightly colored dots inside a black flask, the painter of Splendor solis opted to use a figurative symbol, the peacock contained within a glass vessel.

The Peacock Stage, attributed to Jörg Breu the Elder, (German, ca. 1475–1537). Miniature from the illuminated manuscript Splendor solis oder Sonnenglanz, fol. 28r, 1531–32. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, Cod. 78 D 3

At the top of the miniature is an image of Venus in an orange chariot with two doves harnessed to the front. In her left hand she holds an arrow, while her right hand grasps a rope connected to Cupid. Leashed and blindfolded, Cupid balances on one leg at the front of the chariot, poised to shoot an arrow with his bow. The depiction of the planetary goddess, enwreathed by clouds and illumined by a bright light, is accompanied by a winged heart, which is pierced by an arrow and lingers in the sky. Venus’s realm is characterized by pleasure, amusement, joy, and beauty.

Detail of Venus, cupid, doves, and winged heart in The Peacock Stage, attributed to Jörg Breu the Elder, (German, ca. 1475–1537). Miniature from the illuminated manuscript Splendor solis oder Sonnenglanz, fol. 28r, 1531–32. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, Cod. 78 D 3

Surrounding the central panel are images of various outdoor activities in the earthly realm. A courtly scene at the bottom of the miniature illustrates the corporeal pleasures of eating and music.

Detail of the pleasures of eating and music in The Peacock Stage, attributed to Jörg Breu the Elder, (German, ca. 1475–1537). Miniature from the illuminated manuscript Splendor solis oder Sonnenglanz, fol. 28r, 1531–32. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, Cod. 78 D 3

The right side of the painting is dedicated to the rural stratum of society, a rather unusual group for the children of Venus. A peasant fair with a bagpiper and dancing pairs is framed by two lovers caressing in the shade of a tree and a couple setting out on a horse ride.

Detail of the rural stratum in The Peacock Stage, attributed to Jörg Breu the Elder, (German, ca. 1475–1537). Miniature from the illuminated manuscript Splendor solis oder Sonnenglanz, fol. 28r, 1531–32. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, Cod. 78 D 3

The music making, playing, and dancing of the planet-children can be regarded as a prelude to the so-called “Chymical Wedding”—the joining of male and female spirit and body—that reflected alchemists’ aspiration to unite opposites into a cosmic unity. As it happens, the two bird species tied to Venus that appear in the miniature were widely regarded as aphrodisiacs: peacock meat was believed to increase male potency, and dove meat was said to elevate the libido of women.

Merging Venus’s realm with the symbolic peacock, the artist of Splendor solis crafted a novel way of illustrating the mysterious process of alchemy that would reverberate throughout the centuries.

_______

See this illumination of The Peacock Stage in the exhibition The Art of Alchemy at the Getty Research Institute (October 11, 2016–February 12, 2017).

For discussion of an illuminated copy of the Splendor solis in the British Library, see Jörg Völlnagel, “Harley MS. 3469: Splendor Solis or Splendour of the Sun—A German Alchemical Manuscript” in The Electronic British Library Journal (eBLJ) 2011, Article 8, available online here.

Very interesting! Best! E.S.