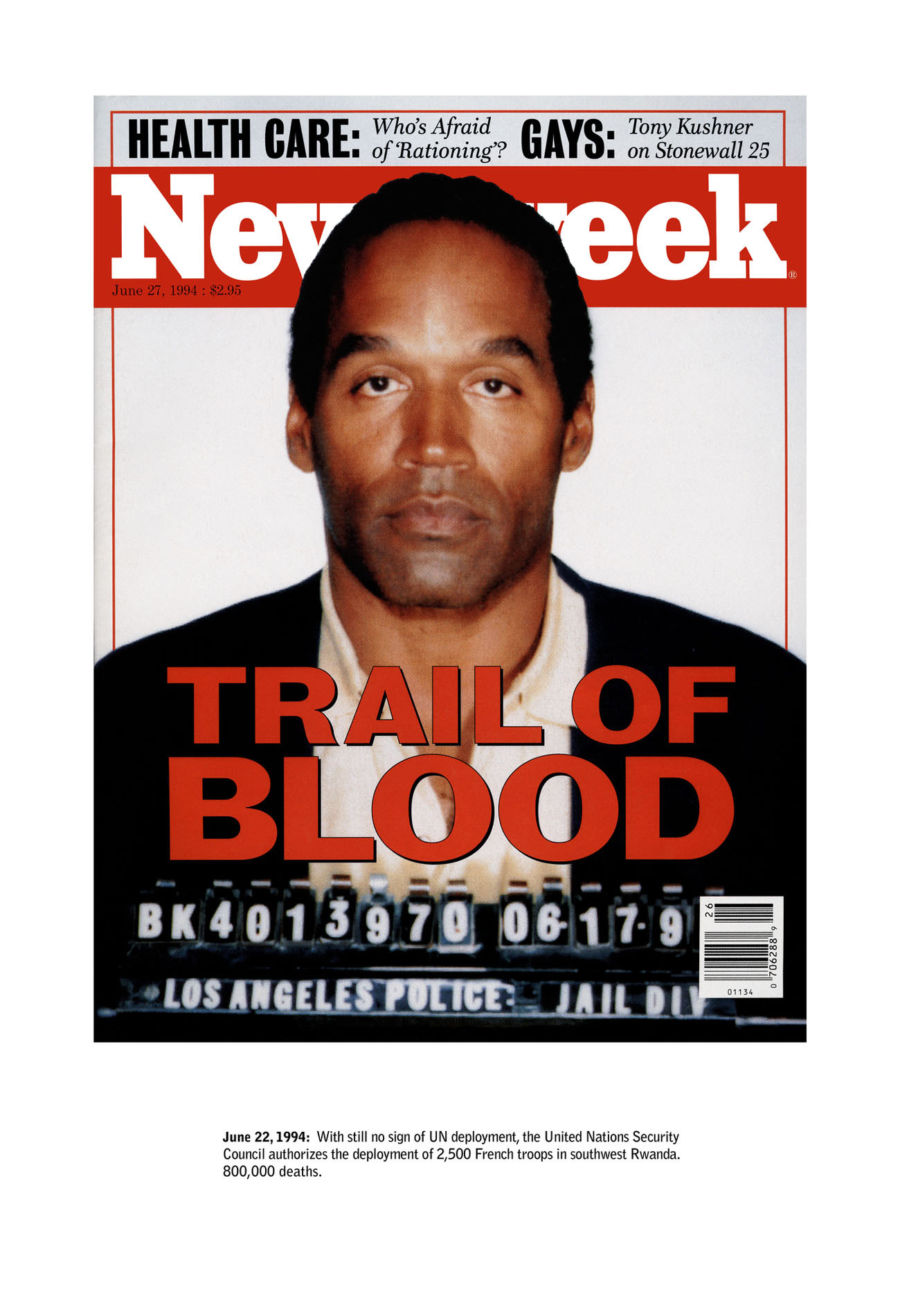

Untitled from the series Untitled (Newsweek), 1995, Alfredo Jaar. Inkjet print, 19 × 13 in. Courtesy Alfredo Jaar and Galerie Lelong, New York. © Alfredo Jaar, courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York

Artist, architect, and filmmaker Alfredo Jaar is deeply concerned with global issues and social justice. He’s also interested in how mass media images travel and their effect on viewers. And how art can intervene.

Jaar’s work often begins with a single real-life event, then grows with his effort to understand, reflect on, and respond to it. Over the course of six years, Jaar crafted many responses to the Rwandan genocide, which he gathered under the title, “The Rwanda Project.” “I think this work falls into the category of people trying to make sense of the world,” he says.

One of these works—a series of Newsweek covers—is included in an exhibition at the Getty Museum, Breaking News: Turning the Lens on Mass Media (December 20, 2016–April 3, 2017).

I interviewed Jaar for the audio tour (two tracks are embedded below, and the full tour is available free online), but the conversation soon moved beyond specific objects in the exhibition.

Alfredo Jaar: It was May 5th, 1994. Like every morning, I was starting my readings with the New York Times, and there was a story in the Times about 30,000 bodies washing down the Kagera River, which is in Lake Victoria near Rwanda. And that story was a very short story buried on page 7. At that moment, I felt an enormous amount of rage, and that’s when I decided to go to Rwanda.

Laura Hubber: How did you think going there would make a difference?

AJ: I had been following the Rwanda events for quite a while. When the genocide started, I started accumulating as much information as I could find from the press. I was looking at the world media in seven different languages. These are pre-internet times. And I was watching with horror at how the international community was criminally indifferent to what was happening there.

I felt that I needed to report it in a different way than it was being reported. Of course it was a futile attempt and an illusion, but still I had to try my best.

LH: How would you describe the coverage of the genocide in Rwanda as it unfolded in the media?

AJ: I would qualify it as barbaric. It was a barbaric indifference. People were dying in the thousands and the stories were buried in main newspapers in page 5 or 7.

LH: Why do you think there was such a global indifference to what was happening in Rwanda given the magnitude of the genocide?

AJ: Because there is no oil in Rwanda, because Rwanda is poor, because Rwandans are blacks, and because Rwanda’s in Africa.

LH: As an artist, what was your strategy to call attention to this situation?

AJ: I documented the genocide with photography, with film, and I spoke with as many survivors as possible. Then I came back to New York and spent a few months thinking about what could possibly be done out of this material.

LH: You chose not to picture or use pictures of actual violence in Rwanda. Why did you make that choice?

AJ: Well, the Rwanda project lasted six years, and I realized twenty-five different projects that I called Exercises in Representation. And most of them tries a different strategy of representation because the traditional strategies of representation had failed to convey what happened and no one had reacted.

LH: Could you describe your Newsweek series?

AJ: Newsweek is from 1994 and is one of the first works from the Rwanda project. It’s a sequence of seventeen covers of the magazine—from April 1994 when the genocide started, until August 1st, 1994, seventeen weeks later, when Newsweek magazine finally decided to put Rwanda on its cover.

LH: But you don’t just include the magazine covers, you also include text.

AJ: Yes. I create a sequence where I produce the cover of the magazine and I also add the date and the events in Rwanda during that week. Basically, I wanted to show the criminal indifference of the magazine to what was happening in Rwanda at the time. A million people were killed in less than 100 days, and Newsweek magazine took seventeen weeks to feature it on its cover.

LH: The final cover text [over an image of a child in a refugee camp] says, “Hell on Earth.” Could you explain just what that cover is.

AJ: It’s a very cynical cover in a sense, because it says, “Hell on Earth,” and it’s too late. It’s been hell on Earth for the last seventeen weeks. When that cover came out, the genocide had ended already and the press was already starting to focus on the plight of the refugees around Rwanda and those displaced within Rwanda.

LH: You were there with photojournalists who do their best to bring back to people what they’re witnessing in the field. How do you see the difference between a photojournalist’s work and an artist’s work?

AJ: I admire photojournalists. I find them everywhere I go and they’re trying to convey the reality of the world to the world community. And, for me, photojournalists and NGOs (non-governmental organizations) are signs of solidarity in a landscape of tragedy and destruction. So I admire them deeply. But the difference is that I have much more time than they have. They are running around with these huge cameras, taking photographs and sending them to photo agencies to be published as soon as possible. They don’t control the way these images are presented to the world.

In my case, I can spend an entire afternoon with my little microphone, recording a conversation with a survivor, and my camera is quite ridiculous, to tell you the truth, compared to their cameras because I’m not interested in photography. I’m there to express solidarity and try to witness this reality and try later to convey it to my audience.

LH: They have just a short window when their images will be used or disseminated through newspapers, but you have a much longer time to reflect.

AJ: Absolutely, but they have the larger audience and I have a smaller one.

LH: As an artist, what do you feel your ethical role is when doing a project like this?

AJ: Every project of mine reacts to a specific event. In this case, the Rwanda tragedy. And I felt that the Rwandan people deserved better than what the world media had done with the genocide and so I went to witness it and I tried to convey the suffering and the pain and the tragedy that the genocide meant for the Rwandan people. And I wanted to convey also that some people in the so-called “western world,” from the so-called “world community,” cared about their state.

LH: What is the most an artist can hope for from their work?

AJ: Well, a work like this tries to inform people and to move them. A work like this tries to touch people and illuminate them. So, when similar events might happen in the future, they might read them differently.

LH: What’s your personal connection with Africa?

AJ: I lived ten years of my life in a small French island called Martinique, which is a black island. It’s a French department. And this is the birth country of Aimé Césaire and Frantz Fanon, the founders of the anti-colonialist movement called Négritude. I actually went to school to the Lycée Schoelcher, which was the school of Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire and others.

So, that experience made me create very strong links with the African race and when I moved to New York in the early ’80s, I immediately realized that in spite of what I had read about the Civil Rights struggles and so on, there was still an enormous amount of racism in the United States and I decided to focus on this subject.

LH: And do you feel, twenty years on, that there’s been movement in a positive direction in representing Africa in the western media?

AJ: I wish I could say yes, but no. Unfortunately, no. I’m afraid nothing has changed.

And what’s happening in the streets of our cities is the most terrible demonstration that we are still living in the middle of a quite racist society.

_______

The mobile audio tour for Breaking News is available free online and also offered on GettyGuide®. Free multimedia players and headphones are available in the Museum Entrance Hall.

Hear Alfredo Jaar speak about his work at the Getty Center on February 23, 2017. Free tickets are available here.

Comments on this post are now closed.