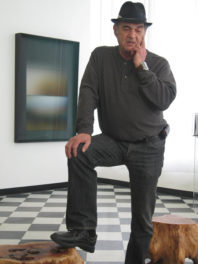

On January 8 sculptor John Mason opened his studio and shared insights into his creative process with us and a group of eager participants. The event was part of “In Studio,” a program we in the Museum’s Education Department organized featuring six artists whose work was included in the exhibition Pacific Standard Time: Crosscurrents.

The following questions grew out of that visit.

You’ve had an interest in patterns, rhythm, and geometry throughout your career. Can you discuss your commitment to modular forms?

One way of thinking of modules is that they are interchangeable. They have the same form; they are equivalent. Modern societies are based on that concept: if you need a particular screw, nail, or bolt, you specify what the name of it is, and you will get the exact thing. It’s a specific form of identity.

It’s fundamental to an industrial society. We are long past the time when it was necessary to make nails by hand, hammer them out one by one.

Why did I choose modular forms? I didn’t have to make all the parts by myself. At first, they existed as manufactured forms, interchangeable units as in the firebrick structures. I did it because I wanted the challenge of working with certain givens, certain units.

The recent orbits, walls, and totems are all modular. They were cut out of clay with a pattern that had one shape, and one shape only, combined in a variety of ways to make a structure, or a sculpture. And the challenge was: How varied could the combination be without violating the premise? One form, replicated and combined.

View into John Mason’s studio kiln, January 8, 2012

In your studio, we talked a lot about technique. You mentioned innate challenges in clay’s physical properties and showed us some of the ways you modified tools, like the slab roller and extruder, to suit your needs. What is the relationship between creativity and limitations?

It’s fundamental! The creative act has to solve that problem! I guess it’s also called thinking, and rethinking.

If I want do something, how do I do it? I have to figure out how. I have to get beyond the limitations. Sometimes technique gets in the way, because people get used to doing certain things in a certain way, but it doesn’t always get you there. Skill and technique are a double-edged sword; they solve some problems and keep you from solving others.

What is the simplest way to solve the problem? Ockham’s Razor: the simplest way is the objective.

John Mason discusses his work with course participants

You’ve cited your teachers Susan Peterson and Peter Voulkos as key mentors. What did they show you? How did they influence the trajectory of your career?

They both encouraged me to find my own way. They were both role models. They were single-minded and they had the courage to pursue the unknown and find meaning in that area.

You, in turn, have taught at a number of universities, including Berkeley, Pomona, and Irvine. What qualities do you think are most important for a teacher to bring to the classroom?

Respect for all participants. Because teaching and learning is a joint effort. Or maybe it should be learning and teaching…either way is all right. I guess learning should be first.

Text of this post © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved.

Comments on this post are now closed.